Archive

2021

KubaParis

Between the use of the object and the contemplation of the specific

Location

GALERÍA GALERÍADate

23.04 –19.05.2021Photography

Manolo MárquezText

Copy Is the Only Route

In the practice of Marek Wolfryd (Mexico City, 1989), appropriation, copy, plagiarism and citation serve as constants to interrogate images in the West. Above all, a desire persists to expand the limits of authorship and originality in favor of a poetic of fair use, where the art is part of a network of signs woven by a semionaut1; the artist, just a link of chains among a chain of production, distribution, commodification and consumption.

Wolfryd's relationship with art history, guided by curiosity, is ambivalent and comprehensive. Each of his series focuses on a specific period that, not being understood in a monolithic way, interconnects with other points in history, tracing a story that collapses past and present. His transhistoric artifacts, stripped of the need to be read univocally as art objects, connect distant temporalities to each other. The exercise of readability starts a conversation, plays with a hypothesis, without an a priori solution that defines individual perception.

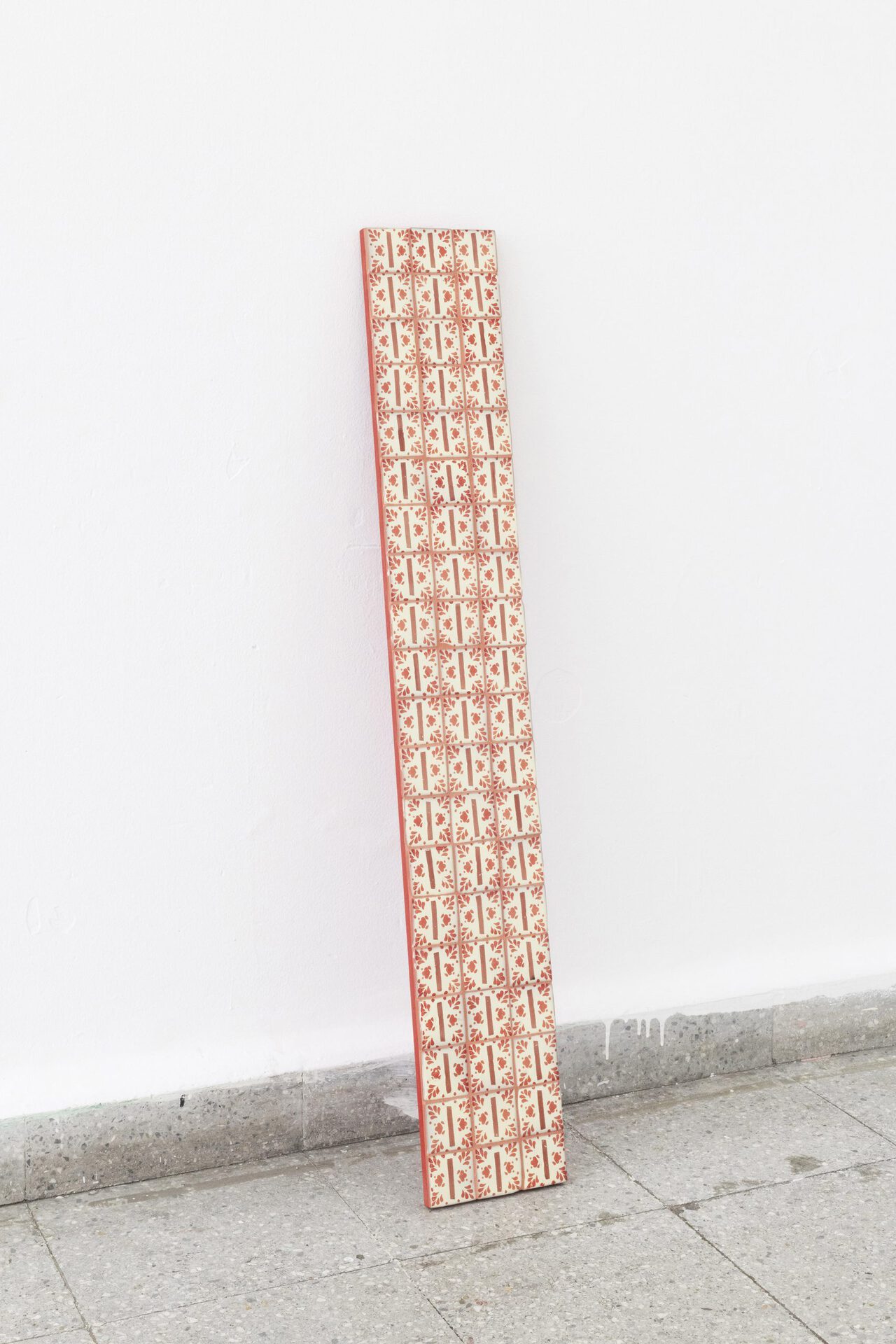

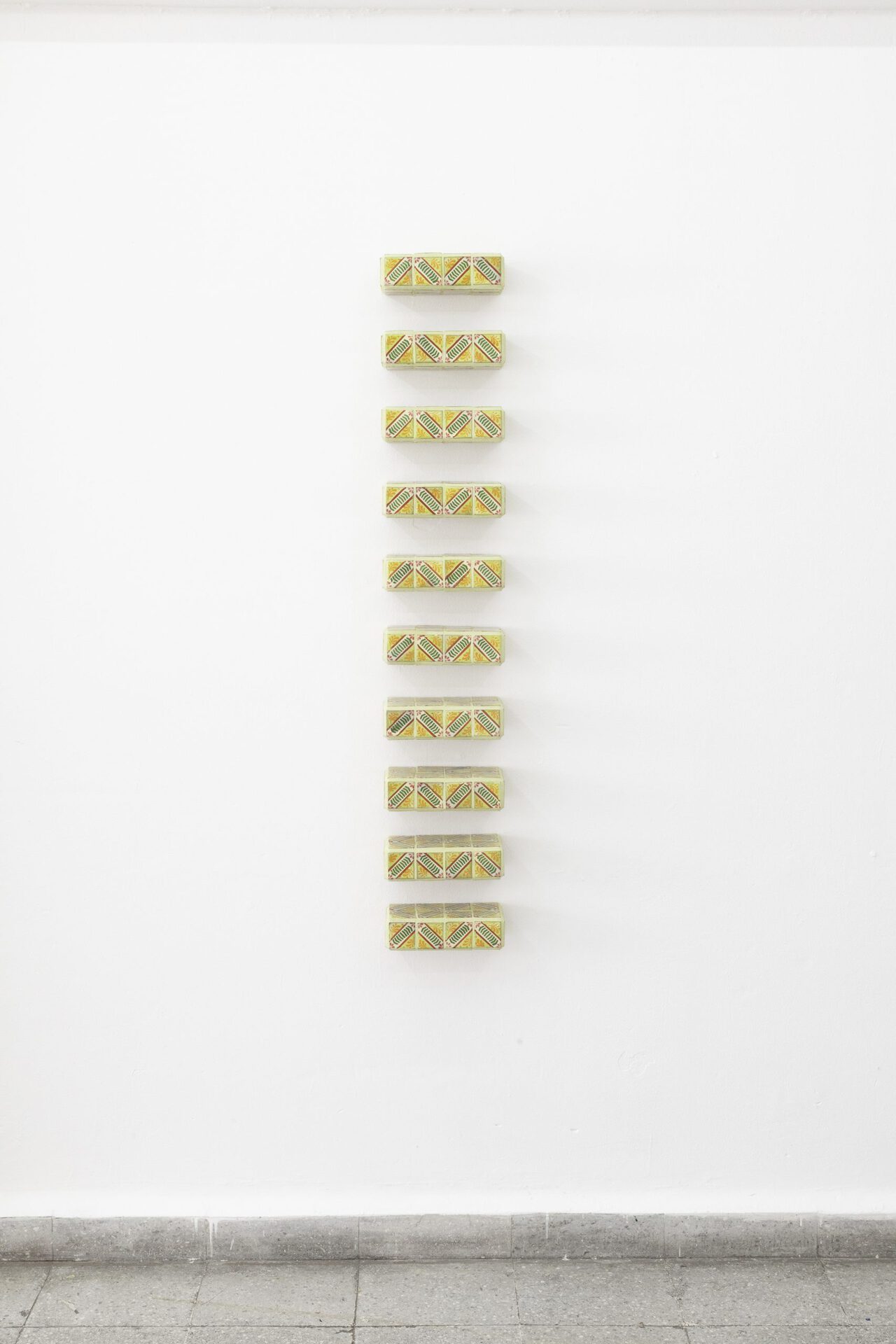

Between the use of the object and the contemplation of the specific (2021) proposes a new way of reading North American minimalism from a peripherical context. In its early days, minimalism faced adverse views by a school of criticism that advocated for Abstract Expressionism, causing a breaking point in the United States in the early 1960s. Long before falling into a rhetoric of assertiveness of predominantly male power2, this art movement strived to break the guidelines of modernist painting and sculpture, which focused on the autonomy of the object and its intrinsic compositional values, to enhance the experience beyond the object, including the corporality of the spectator and his/her/their visual field. Minimalist attitude advocated for the simplicity of shapes, which, according to Robert Morris, "does not necessarily equate with simplicity of experience”3.

In this minimized minimalism, the material sets the production tone: the colors sometimes emulate the model; the shapes, above everything else, are identical. The scale reduction of the original three-dimensional works operates according to the overlay: talavera tiles designed specifically to mimic, in turn, the geometrical lines of the objects they cover, generating a kind of illusion between the surface and its details. This gesture should be understood as a speculative ornamentation that, once again, points to the history of materials. Let us remember that, from its roots, talavera tiles are a material of complex origins, a hybrid product with a clear Mudejar imprint brought to Latin America from Spain. Although there is a record of the ordinances in charge of giving law and order to the production of talavera during the Spanish colonization of the Americas, we can assert that it is a material with unsteady authorship, recreated through copies from original models.

It is from this principle that the artist questions the industrialized appliance of talavera through the usage of construction tiles, without ruling out the possibility that the artifacts can be considered artisanal. This body of work makes the craft and the artistic fluctuating categories, which transform or collide within the same object. According to Octavio Paz, "in craftsmanship there is a continuous movement back and forth between usefulness and beauty".4 However, we cannot idealize the artisan object. The construction of the post-revolutionary state in Mexico systematically eroded the authorship traces behind handcrafts, instrumentalizing them for political, cultural and diplomatic purposes. In craft —Wolfryd reminds us— there is a lot of copy, illegibility and anonymity.

It would be reiterative to point out that Marek Wolfryd's practice shares discursive and aesthetic features related to postmodernism (in this globalized panorama, what practice would be exempt?). Indeed, his work highlights the “exhaustion”5 of the conventions of the production, circulation and commodification of art in contemporary times. It is not a pessimistic vision, but rather a revision, renewal and recirculation of ideas that seem to have been long ago assimilated. Thus, by inspecting the nooks and crannies of North American “literalism” for its appropriation and resignification, Wolfryd invites us to contemplate not only the object per se, but also its organization and function within the space, as a unity and as a whole, even if these works have been cited previously. However, is it really possible to give appropriation a radical position? Which direction to take if originality has worn off? Perhaps it would be necessary to appeal to the slogan: Copy Is the Only Route.

Juan Pablo Ramos

(@elguaruradelucero)

1.- Nicolás Bourriaud, “Postproduction”, London, Sternberg Press, 2005, p. 14.

2.- Anna C. Chave, “Minimalism and the Rethoric of Power” in Art in Modern Culture. An Anthology of Critical Texts, ed. Francis Franscina & Jonathan Harris, New York, Phaidon Press, 2011, pp. 264-281.

3.- Robert Morris, “Notes on Sculpture, in Minimal Art. A Critical Anthology”, ed. Gregory Battcock, New York, E. P. Dutton, 1968, p. 228.

4.- Octavio Paz, “Seeing and Using: Art and Craftsmanship” in Convergences: Essays on Art and Literature, San Diego, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1987, pp. 50-67.

5.- The term exhaustion appears, coincidentally, in a key text on American minimalism published in 1967, "Art and Objecthood" by Michael Fried. That same year, John Barth published the essay "The Literature of Exhaustion", which outlined common motifs in postmodern literature.

Juan Pablo Ramos @elguaruradelucero