Archive

null

KubaParis

strange-cloud-that-hangs-over-all-of-us-an-interview-with-candice-lin-by-yvonne-scheja

Location

Kunsthalle Osnabrück's IGSubheadline

Candice Lin explores in many ways how colonial history, which has long been one-sided and still only partially dealt with, continues to shape our present. In doing so, she repeatedly exposes how our history repeats itself and at the same time how our everyday objects are historically charged.Text

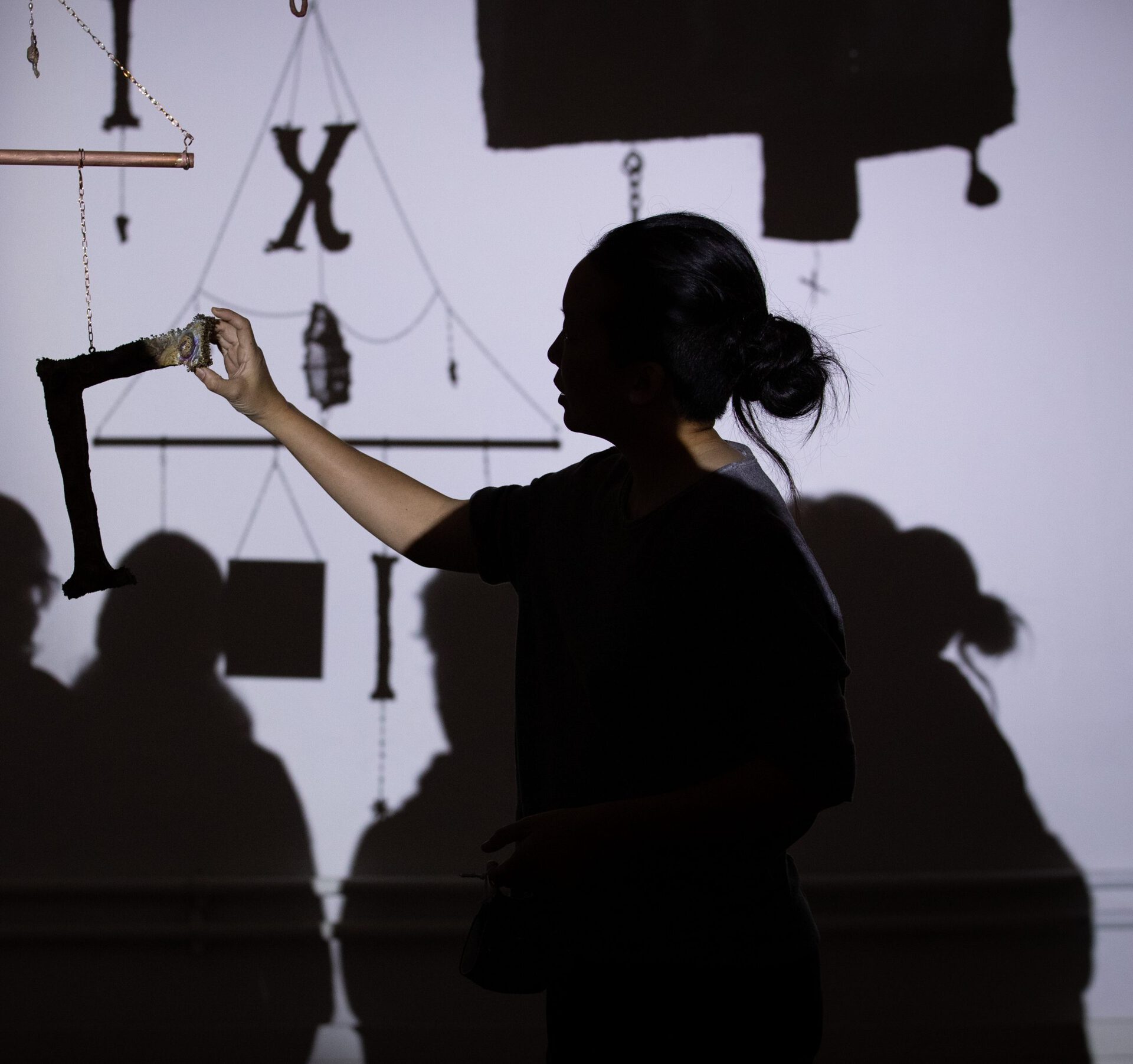

Candice Lin. Photo: Friso Gentsch (above)

The Glittering Cloud, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

The Glittering Cloud, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

Candice Lin, The Glittering Cloud, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Friso Gentsch

YS: When we were talking in the exhibition space, you said you already developed parts of the work beforehand, like Vermin Visionary (Copper Version), the sculpture of a life-size trebuchet. How much do your works overlap in general?

CL: I feel like every time I'm making an exhibition, if two exhibitions are taking place close in time, they end up bleeding together. There's a lot of crossover in this exhibition with the works I created for “Pigs and Poison” which was shown 2020 and 2021 and will open at Spike Island in February next year. That presentation looks at the history of 19th century indentured Asian labor and includes the trebuchet sculpture which is recreated in a new form for Kunsthalle Osnabrück. It references an early moment where racial, cultural or religious differences were linked to fears of contamination and disease: the 1346 siege of Kaffa [Feodosia, Crimea], where it is said that the Mongolian Army catapulted the dead, plague-infected bodies of people and horses into the city. When the siege broke, those people fleeing the city supposedly brought the disease into Europe. It is this early moment of biological warfare where the diseased body is weaponized and where disease and contamination are associated with the Eastern and Islamic other. So I thought it would be interesting to recontextualize this earlier sculpture in the Kunsthalle Osnabruck, where it is painted a weather-beaten copper—tying it formally into other works in the show—and is launching projectiles with gold confetti, rather than bone-black pigment and lard as was the case in “Pigs and Poison”.

YS: How much influence does your research have on your work?

CL: Sometimes I get ideas from books I am reading or from experimenting with the material in a hands-on way. Sometimes I get ideas from radio shows or podcasts I listen to in the studio or in my long commute to the university I teach at. My practice is research driven but I also think it is important for people to just experience the artwork and not necessarily overburden the work with all the historical references. I make art because it communicates differently than writing. It impacts the body sensorially and emotionally and I think that’s important. So it may be that people come and just see this trebuchet without reading about it and they might not understand the reference, but I think they will feel the impact and power of this brute weapon and its potential to hurt you, and they will potentially feel the joy and glee that happens when the projectile bursts and gold confetti fills the air, and they will be implicated in those emotional reactions. So I think there's different layers of meaning and feeling that people can get from it.

Candice Lin, The Glittering Cloud, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Friso Gentsch

YS: When we were talking in the exhibition space, you said you already developed parts of the work beforehand, like Vermin Visionary (Copper Version), the sculpture of a life-size trebuchet. How much do your works overlap in general?

CL: I feel like every time I'm making an exhibition, if two exhibitions are taking place close in time, they end up bleeding together. There's a lot of crossover in this exhibition with the works I created for “Pigs and Poison” which was shown 2020 and 2021 and will open at Spike Island in February next year. That presentation looks at the history of 19th century indentured Asian labor and includes the trebuchet sculpture which is recreated in a new form for Kunsthalle Osnabrück. It references an early moment where racial, cultural or religious differences were linked to fears of contamination and disease: the 1346 siege of Kaffa [Feodosia, Crimea], where it is said that the Mongolian Army catapulted the dead, plague-infected bodies of people and horses into the city. When the siege broke, those people fleeing the city supposedly brought the disease into Europe. It is this early moment of biological warfare where the diseased body is weaponized and where disease and contamination are associated with the Eastern and Islamic other. So I thought it would be interesting to recontextualize this earlier sculpture in the Kunsthalle Osnabruck, where it is painted a weather-beaten copper—tying it formally into other works in the show—and is launching projectiles with gold confetti, rather than bone-black pigment and lard as was the case in “Pigs and Poison”.

YS: How much influence does your research have on your work?

CL: Sometimes I get ideas from books I am reading or from experimenting with the material in a hands-on way. Sometimes I get ideas from radio shows or podcasts I listen to in the studio or in my long commute to the university I teach at. My practice is research driven but I also think it is important for people to just experience the artwork and not necessarily overburden the work with all the historical references. I make art because it communicates differently than writing. It impacts the body sensorially and emotionally and I think that’s important. So it may be that people come and just see this trebuchet without reading about it and they might not understand the reference, but I think they will feel the impact and power of this brute weapon and its potential to hurt you, and they will potentially feel the joy and glee that happens when the projectile bursts and gold confetti fills the air, and they will be implicated in those emotional reactions. So I think there's different layers of meaning and feeling that people can get from it.

Candice Lin, Vermin Visionary (copper), copper painted wood, confetti, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

Candice Lin, Vermin Visionary (copper), copper painted wood, confetti, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

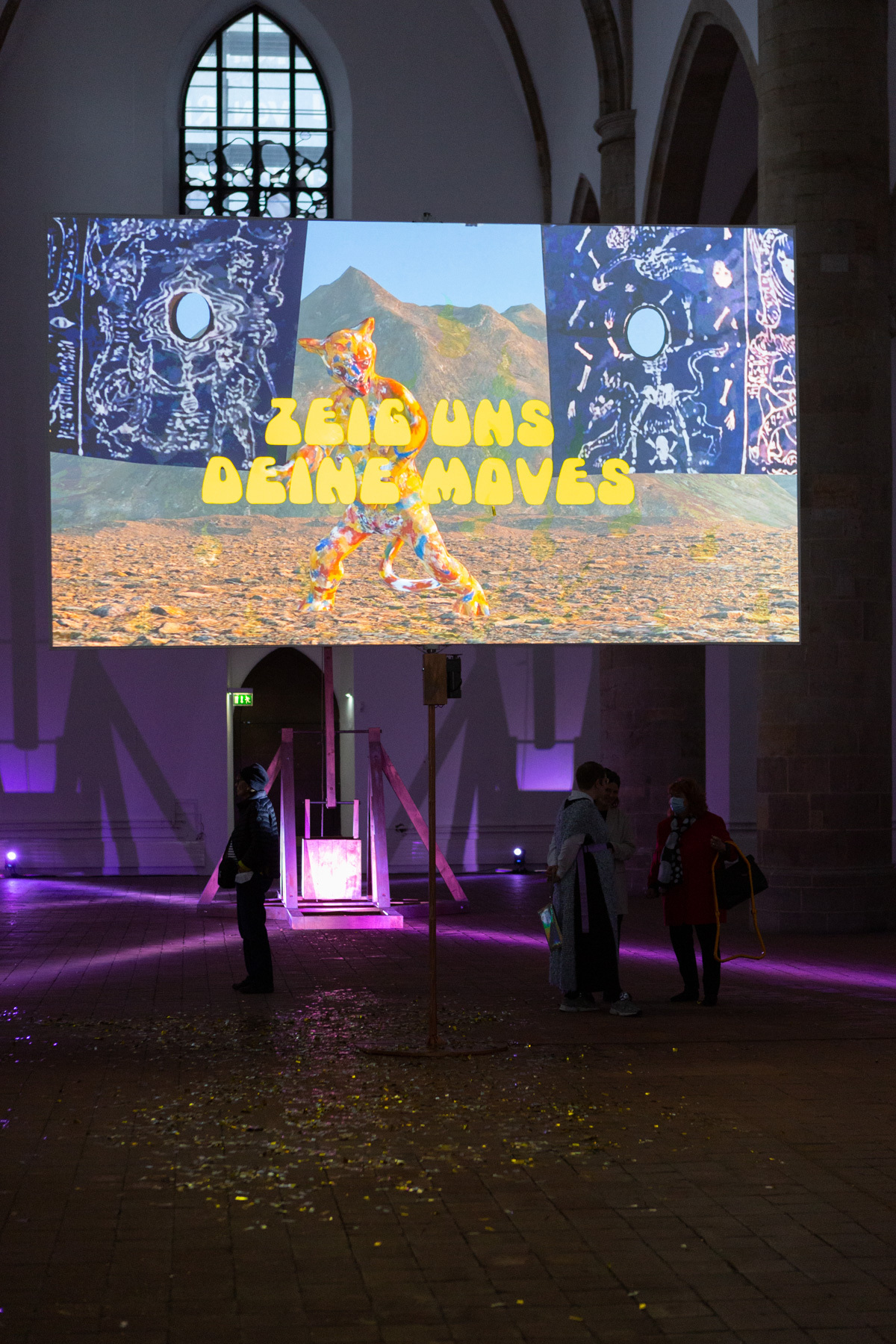

CL: His whole pseudo-ethnography is really incredible. I am mainly interested in this idea of racial performance and the amount of creativity and imagination he used. And also what it reveals around the stereotypes and projections of what it meant to be Asian within the European imagination at that time. To get back to the demons, In Psalmanazar’s case, the demon represents the savagery of the racial other, it is placated by being sacrificed baby boys. Also present in the exhibition, and connected to thinking about the rituals around warding off evil and illness, was the video projection, which shows a cat-demon with multiple breasts, leading people on qigong exercises in a desolate landscape. Within this exhibition, this video spoke to ideas of wellness and the way wellness is capitalized on in the wellness industry, where Western appropriation of Eastern belief systems like qigong hold a kind of power and fascination because of their exoticness and foreignness, and I’m fascinated by how they transform into something else within the wellness industry. So the installation combines all these different layers in thinking through accessibility in relationship to cultural or racial otherness, and health and wellness.

CL: His whole pseudo-ethnography is really incredible. I am mainly interested in this idea of racial performance and the amount of creativity and imagination he used. And also what it reveals around the stereotypes and projections of what it meant to be Asian within the European imagination at that time. To get back to the demons, In Psalmanazar’s case, the demon represents the savagery of the racial other, it is placated by being sacrificed baby boys. Also present in the exhibition, and connected to thinking about the rituals around warding off evil and illness, was the video projection, which shows a cat-demon with multiple breasts, leading people on qigong exercises in a desolate landscape. Within this exhibition, this video spoke to ideas of wellness and the way wellness is capitalized on in the wellness industry, where Western appropriation of Eastern belief systems like qigong hold a kind of power and fascination because of their exoticness and foreignness, and I’m fascinated by how they transform into something else within the wellness industry. So the installation combines all these different layers in thinking through accessibility in relationship to cultural or racial otherness, and health and wellness.

The Glittering Cloud, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

In a conversation at the Kunsthalle Osnabrück about her current exhibition "The Glittering Cloud", Candice Lin talks about the development of her works and how they overlap, as well as the influences that shape her most recent presentation. YS: Maybe the question is too obvious: How much did the building – a former church – influence the creation of your exhibition “The Glittering Cloud”? The space itself is filled with a great deal of history and might have more of an impact on the installation of the exhibition than showing in a white cube. CL: A lot of my previous work from 2016-2017 was very site specific, where I would visit a place and research something specific to the place. Due to Coronavirus, I wasn't able to do that with this exhibition. But I was thinking about how to make my work, which has been about histories of colonialism and colonial trade, address the fact of being shown in a former church. YS: How would you describe the topics you are dealing with in your exhibition? CL: When Juliane and Anna shared that the theme of their program in 2021 was accessibility, I really had to think about it for a long time because I think there are a lot of assumptions around what makes something accessible and what makes something inaccessible. I was curious about how the notion of accessibility might be tied to other Western ideas like universality and transparency. I wondered how much of the urge to make something accessible might end up creating a projection and fantasy of what the other—imagined through one’s own embodiment—needs, thoughts or beliefs. A lot of my work has looked at the cultural fetishism or exoticism in colonially traded materials, and how those objects became valuable often through being inaccessible, rare or unknowable. For instance, when I was researching cochineal for an installation I made in 2016, System for a Stain, I learned that in the 16th century Europeans were not sure if the dried cochineal the Spanish were importing from their colonies to make red dye was a grain, a mineral, or a seed. And the Spanish actively encouraged obscuring the fact that it was an insect—partially to preserve the secrets of its manufacture and to create value around its mystery. So it becomes a site of projection. I was thinking about Édouard Glissant’s “right to opacity” and Denise Ferreira de Silva's “transparency thesis”. I wanted to trouble the idea of accessibility as this idea that anything or anyone can be made transparent, accessed and known fully, and to look instead at moments of cultural projection or misunderstanding. The Glittering Cloud, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

The Glittering Cloud, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

Candice Lin, The Glittering Cloud, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Friso Gentsch

YS: When we were talking in the exhibition space, you said you already developed parts of the work beforehand, like Vermin Visionary (Copper Version), the sculpture of a life-size trebuchet. How much do your works overlap in general?

CL: I feel like every time I'm making an exhibition, if two exhibitions are taking place close in time, they end up bleeding together. There's a lot of crossover in this exhibition with the works I created for “Pigs and Poison” which was shown 2020 and 2021 and will open at Spike Island in February next year. That presentation looks at the history of 19th century indentured Asian labor and includes the trebuchet sculpture which is recreated in a new form for Kunsthalle Osnabrück. It references an early moment where racial, cultural or religious differences were linked to fears of contamination and disease: the 1346 siege of Kaffa [Feodosia, Crimea], where it is said that the Mongolian Army catapulted the dead, plague-infected bodies of people and horses into the city. When the siege broke, those people fleeing the city supposedly brought the disease into Europe. It is this early moment of biological warfare where the diseased body is weaponized and where disease and contamination are associated with the Eastern and Islamic other. So I thought it would be interesting to recontextualize this earlier sculpture in the Kunsthalle Osnabruck, where it is painted a weather-beaten copper—tying it formally into other works in the show—and is launching projectiles with gold confetti, rather than bone-black pigment and lard as was the case in “Pigs and Poison”.

YS: How much influence does your research have on your work?

CL: Sometimes I get ideas from books I am reading or from experimenting with the material in a hands-on way. Sometimes I get ideas from radio shows or podcasts I listen to in the studio or in my long commute to the university I teach at. My practice is research driven but I also think it is important for people to just experience the artwork and not necessarily overburden the work with all the historical references. I make art because it communicates differently than writing. It impacts the body sensorially and emotionally and I think that’s important. So it may be that people come and just see this trebuchet without reading about it and they might not understand the reference, but I think they will feel the impact and power of this brute weapon and its potential to hurt you, and they will potentially feel the joy and glee that happens when the projectile bursts and gold confetti fills the air, and they will be implicated in those emotional reactions. So I think there's different layers of meaning and feeling that people can get from it.

Candice Lin, The Glittering Cloud, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Friso Gentsch

YS: When we were talking in the exhibition space, you said you already developed parts of the work beforehand, like Vermin Visionary (Copper Version), the sculpture of a life-size trebuchet. How much do your works overlap in general?

CL: I feel like every time I'm making an exhibition, if two exhibitions are taking place close in time, they end up bleeding together. There's a lot of crossover in this exhibition with the works I created for “Pigs and Poison” which was shown 2020 and 2021 and will open at Spike Island in February next year. That presentation looks at the history of 19th century indentured Asian labor and includes the trebuchet sculpture which is recreated in a new form for Kunsthalle Osnabrück. It references an early moment where racial, cultural or religious differences were linked to fears of contamination and disease: the 1346 siege of Kaffa [Feodosia, Crimea], where it is said that the Mongolian Army catapulted the dead, plague-infected bodies of people and horses into the city. When the siege broke, those people fleeing the city supposedly brought the disease into Europe. It is this early moment of biological warfare where the diseased body is weaponized and where disease and contamination are associated with the Eastern and Islamic other. So I thought it would be interesting to recontextualize this earlier sculpture in the Kunsthalle Osnabruck, where it is painted a weather-beaten copper—tying it formally into other works in the show—and is launching projectiles with gold confetti, rather than bone-black pigment and lard as was the case in “Pigs and Poison”.

YS: How much influence does your research have on your work?

CL: Sometimes I get ideas from books I am reading or from experimenting with the material in a hands-on way. Sometimes I get ideas from radio shows or podcasts I listen to in the studio or in my long commute to the university I teach at. My practice is research driven but I also think it is important for people to just experience the artwork and not necessarily overburden the work with all the historical references. I make art because it communicates differently than writing. It impacts the body sensorially and emotionally and I think that’s important. So it may be that people come and just see this trebuchet without reading about it and they might not understand the reference, but I think they will feel the impact and power of this brute weapon and its potential to hurt you, and they will potentially feel the joy and glee that happens when the projectile bursts and gold confetti fills the air, and they will be implicated in those emotional reactions. So I think there's different layers of meaning and feeling that people can get from it.

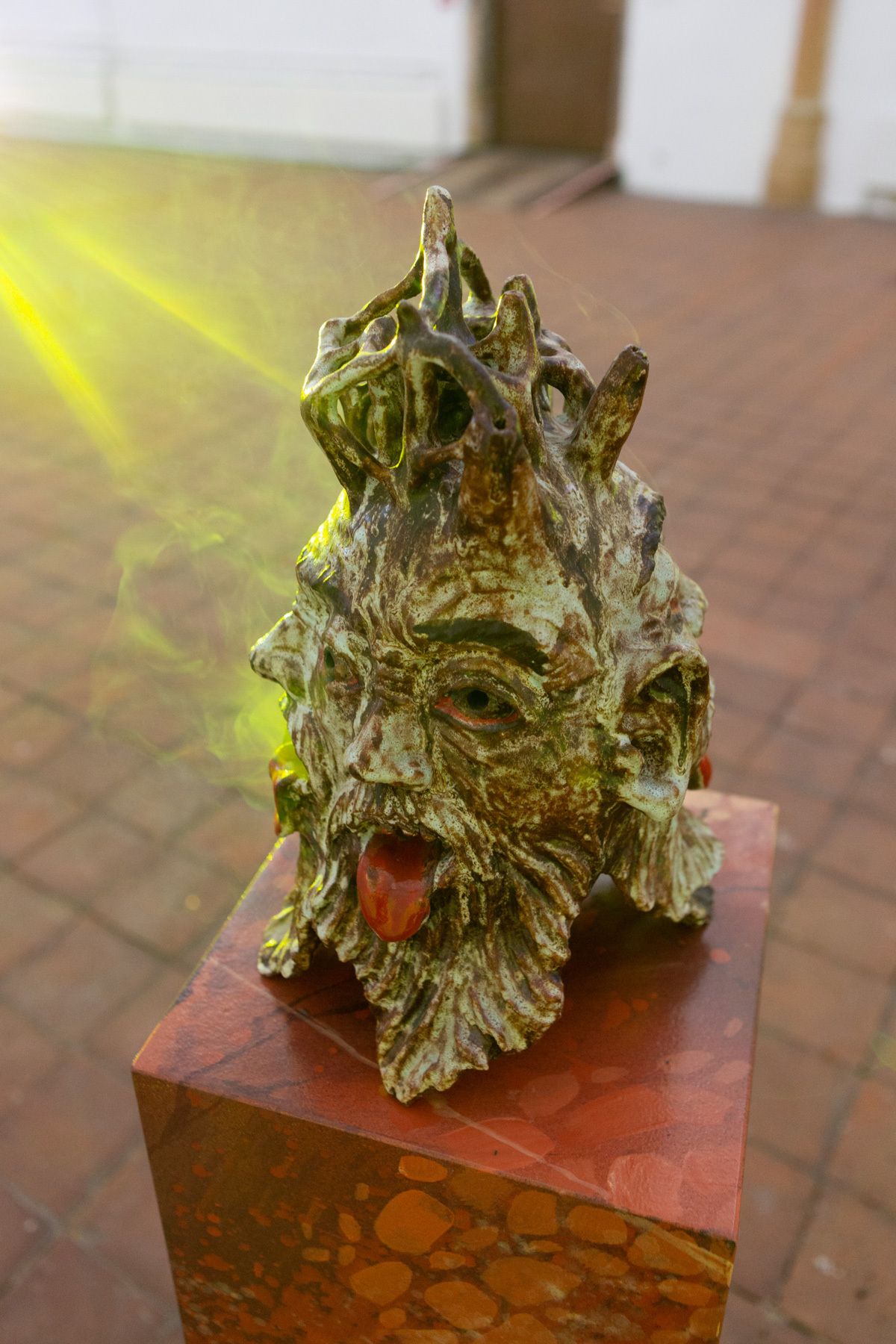

Candice Lin, Swamp Carcass, glazed ceramic, candles, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

YS: It is also important to keep hidden spots within artworks and exhibitions: things people realize or remember later on, tiny details like the talismans. I read a statement where you were talking about the history and that it reveals those kinds of human anxieties or relations that are historical but no longer present.

CL: The talismans come out of research I was doing into Pagan ideas around disease and sickness that then became adopted by a kind of Christian worldview, believing that demons, for example, can be fought off with the use of a “demonic smell” or a bawdy talisman. The talismans that are hanging from the ceiling and a couple of places in the walls of the Church are based on European medieval badges that were found in a river in the Netherlands. They often look like a personified vagina or something taboo like somebody peeing into a mortar and pestle. The theory around their efficacy is that the demon would be trying to go into the body of the person and make them sick. But then they would see this vagina with arms and legs, and the demon would be shocked or allured, and distracted from trying to enter the person. So in adding these hidden talismans, I was trying to bring in these presences that are protecting the people who visit the space, but are also ghosts of colonial history that haunt us even though they may not be seen directly. There are also glow in the dark drawings on the walls and projection screen that only become briefly visible when one of the choreographed moving lights passes over them.

Candice Lin, Vermin Visionary (copper), copper painted wood, confetti, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

Candice Lin, Vermin Visionary (copper), copper painted wood, confetti, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

Foto: Lucie Marsmann/Candice Lin, The Idol of the Devil (Beheaded), glazed ceramic, incense cone, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

YS: It is interesting that in so many countries you have these kinds of ideas to scare demons away by wearing masks or other bizarre looking objects such as in Carnival in Germany.

CL: The demon is always revealing in how it is tied to our feelings of vulnerability and what we imagine could ward it off or distract it – our unconscious desires or taboos. Also how it is imagined to look often reveals our deep-seated fears of the racial or cultural other. George Psalmanazar’s invented religion of Formosa [present day Taiwan]– plays an important role within “The Glittering Cloud” and reveals a lot about the racial fantasy of Europeans imagining who or what the Asiatic other was in the 18th century. Psalmanazar was a European who pretended to be from Formosa and wrote a pseudo-ethnography that described the Formosan language, religion, and customs. Although he was blond and blue eyed, he “passed” as Asian by performing his racial difference through actions like ingesting opium tincture and raw meat spiced with cardamom. His drawing of the “idol of the devil” is referenced in some of the ceramics in the exhibition which are burning an “opium” scented incense.

Candice Lin, Our Father is a Foreigner, textile, copper, wood, epoxy, paint, glass, semi-precious stones, pearls, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

Candice Lin, Our Father is a Foreigner, textile, copper, wood, epoxy, paint, glass, semi-precious stones, pearls, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

YS: I am curious about George Psalmanazar.

CL: Yes, he's a fascinating historical person. Another work in the exhibition also references Psalmanazar, “Our Father is a Foreigner” is a hanging mobile, which is made out of copper electroplated letterforms and Chinese herbs. The letter forms come from his invented alphabet. They are fragments of the Lord’s Prayer. When he was pretending to be from Formosa, he convinced the Bishop of London through his story of religious conversion, and he wrote the Lord's Prayer in his fake Formosan language. It actually ended up in these big books that missionaries would collect the Lord's Prayer in many different languages of peoples the missionaries had converted to Christianity. In the National Museum in Taiwan, there's one of these compendiums that includes the invented Formosan prayer written by George Psalmanazar.

Candice Lin, Our Father is a Foreigner, textile, copper, wood, epoxy, paint, glass, semi-precious stones, pearls, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

Candice Lin, Millifree Work Weary TM Free Video (Qi Gong), video, 19:55 min., 2021, installation view Kunsthalle Osnabrück, 2021. Photo: Lucie Marsmann

YS: Somehow you can say he was extremely creative by inventing a whole language.

Candice Lin The Glittering Cloud 6.11.2021 - 27.2.2022 Kunsthalle Osnabrück

https://kunsthalle.osnabrueck.de/enCourtesy François Ghebaly Gallery: http://ghebaly.com/work/candicelin/

Yvonne Scheja