Archive

2022

KubaParis

Auf dem Asphalt botanisieren gehen

Location

Klosterfelde EditionDate

28.04 –29.07.2022Photography

GRAYSCText

Throughout her practice, Lena Henke produces sculptures and installations that intimately recast histories of modernism, design, and urban planning. Her process begins with research into the physical spaces in which she lives, works, and exhibits her artworks. Henke’s engagements with site-specificity result in sculptures whose often appropriated forms are at once rigorous and flirtatious. Her works challenge the patriarchal legacies of modern culture while bringing the lived experiences of gender to their surfaces. For the past decade, Henke has produced a body of work that explores her personal relation to the architecture and urban design of New York City, where she has continuously lived and worked. For her exhibition at Klosterfelde Edition, Henke shifts her geographic focus to the urban space of Berlin, where she has temporarily relocated. Henke’s new set of sculptures excavates the local histories and household artefacts of the Hansaviertel, a neighborhood comprised of postwar modernist social housing where the artist’s studio is currently located.

Situated between the Tiergarten and the River Spree, the Hansaviertel was once a densely inhabited area with a strong Jewish presence, before being reduced to rubble in World War II. Amid postwar efforts to reconstruct derelict neighborhoods and address housing shortages, West Berlin organized the Internationale Bauaustellung (Interbau) in 1957, in which the top architects of the time— Walter Gropius, Oscar Niemeyer, Alvar Aalto, Werner Düttmann, Le Corbusier, and others—were commissioned to redesign the Hansaviertel. At the core of the Hansaviertel project was an attempt to reshape postwar life through architecture, technology, and the city’s nature. The crisp geometries of new modernist apartments opened onto the Tiergarten’s Stadtgrün, while their interiors were fitted with the latest technologies like underfloor heating and rubbish chutes. The new urban district embodied Cold War aesthetic ideologies, as modernist design served the Western Bloc’s democratic and capitalist ideals. As then Chancellor Konrad Adenauer announced at the time, the Hansaviertel “expresses a connection to the people of the free world.”(1) Through collaboration with international proponents of modernist design to rebuild what the war destroyed, the Hansaviertel was framed as West Berlin’s architectural emancipation from its Nazi past into the foundations of a liberated society.

While looking at archival photographs of Hansaviertel apartments, Henke noticed two recurring features. She observed Braun appliances in numerous interiors, which evoked distant memories of growing up around Braun products in West Germany. Under the direction of the renowned designer Dieter Rams, Braun manufactured fashionable household products whose innovative designs revamped postwar domestic life. In 1957, Braun participated in Interbau; of the model apartments on view in the Hansaviertel, sixty percent were furnished with Braun products.(2) What united Braun and the Hansaviertel was their shared renewal of modernism in postwar design. The politics of this return was exemplified by Ram’s oft-cited design principle, “Back to purity, back

to simplicity!” In equipping domestic spaces with sleek surfaces and functional forms, both Braun and the Hansaviertel sought to expunge post-fascist society with a return to aesthetic simplicity and moral purity. The new apartments and appliances forged blueprints for new ways of living, laboring, and consuming, with technologies of the future at the center of the home.

Henke additionally noticed an awkwardness around kitchen spaces in photographs of Hansaviertel apartments. Minimal and narrow, these kitchens often included a retractable curtain, which provided a backdrop to the leisure space of the living room while hiding the kitchen’s gendered labor. For Henke, these concealable kitchens illustrated the power relations of male architects dictating women’s domestic labor through design, rendering their housework and care work invisible. And unsurprisingly for the time, the protagonist designers of the Hansaviertel and Braun were all men. A decade later, the feminist movement of the 1970s took aim at the kitchen by challenging the patriarchal alignment of women with the domestic realm, as evident in artworks such as Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975). In her manifesto for the renumeration of women’s housework, Silvia Federici diagnosed the problem of feminism as “how to bring this struggle out of the kitchen and into the streets.”(3) In Auf dem Asphalt botanisieren gehen [“To go botanizing on the asphalt”], Lena Henke examines how long histories of design continue to affect gendered experiences of labor and urban space, from the perspective of kitchen appliances appropriated and reproduced into a sculptural scenography.

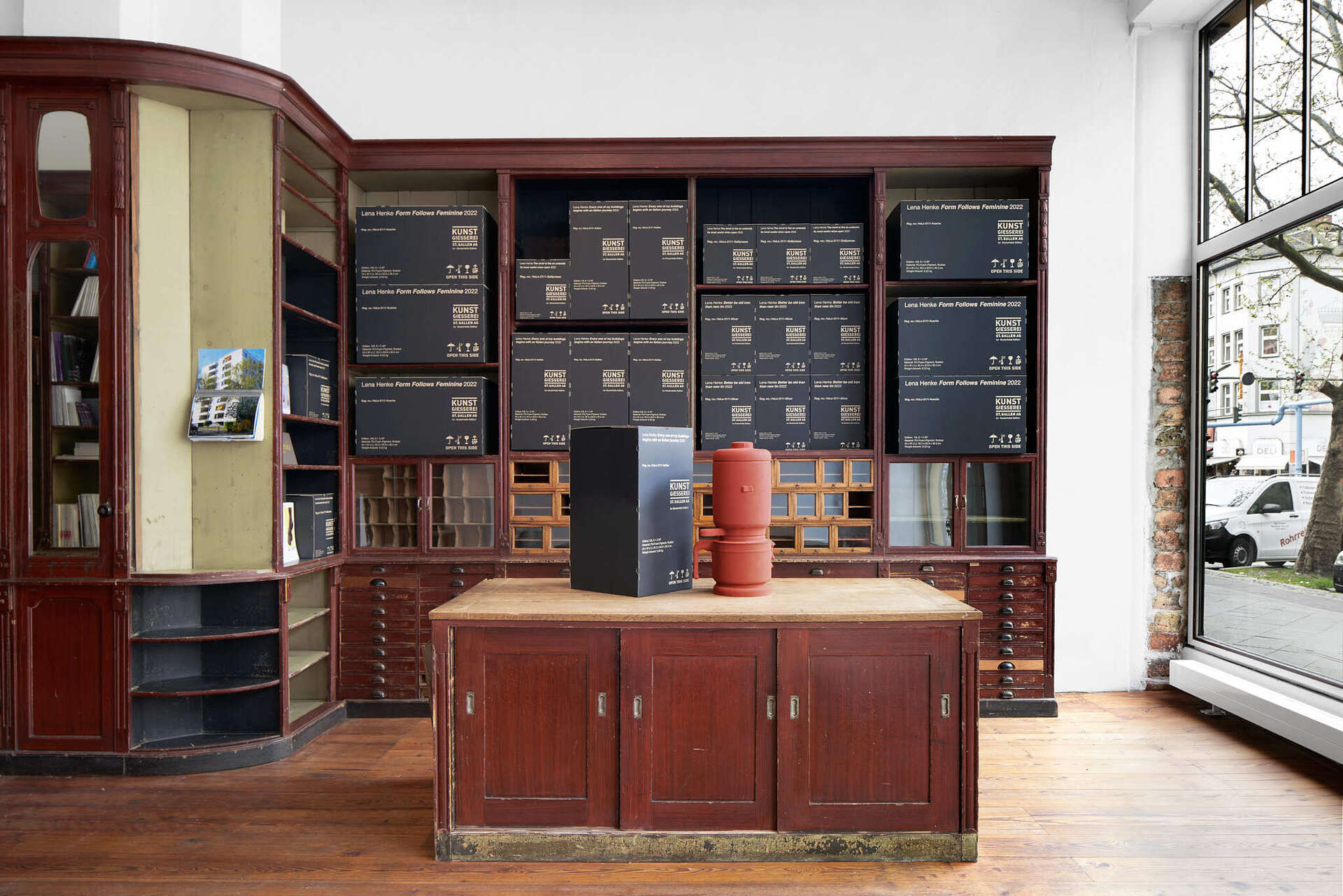

To compose her new series of sculptures on view, Henke digitally reworked four iconic Braun appliances of the postwar era: the KM 3 “Küchenmaschine” stand mixer (1957), the MX 3 mixer (1958), the MPZ 2 “Citromatic” citrus press (1972), and the KF 20 “Aromaster” coffee machine (1972).(4) Each sculptural edition is complemented by the artist’s custom-designed packaging of black carton boxes with individual labels, installed on the counter and shelving adjacent to the gallery’s entrance. The sculptures’ colors are derived from vintage Braun advertisements, while their skin-like rubber surfaces emphasize the appliances’ biomorphic shapes. Henke has retained the physical glitches that occur in the 3D printing process, which materialize on the sculptures as drips, leaks, and overflows. Upon closer inspection, the appliances appear as bodies on the verge of spilling over, their tumescent forms threatening the integrity of their modernist design. In her installation of the sculptures, Henke engages with the physical site of Klosterfelde Edition and its surrounding environs of Potsdamer Straße. The space was originally a lived-in apartment. It was converted into a stationary store, and ultimately a gallery, through the removal of half a floor, which provided a street-level entrance while expanding the height of the narrow space. Henke has repeated a parallel gesture by enlarging her appliance sculptures 1.5 times the size of the Braun originals. Through digitally resizing the kitchen devices, Henke emphasizes their modernist architectural, building-like forms while undermining their domestic functionality; they become solid objects, too big to be used.

Henke has arranged the appliance sculptures on a ramp descending from the small room at the back of the gallery, which was formerly a kitchen. The ramp is covered in green linoleum, a material frequently used for postwar kitchen floors. The ramp extends from the gallery’s former kitchen toward the street, conjuring feminist political entanglements of the personal and public realm. The installation stages further relations to the sidewalk, as if the appliances were architectural models atop a city block. Henke has excerpted the exhibition’s title Auf dem Asphalt botanisieren gehen from

Walter Benjamin’s Das Passagenwerk [The Arcades Project] (1927-1940), in which Benjamin characterizes the figure of the flâneur as an urban wanderer who “goes botanizing on the asphalt.”(5) While “botanizing on the asphalt” recalls the Hansaviertel’s intermixing of concrete architecture and the Tiergarten’s nature, the title further excavates the history of pedestrian movement on Potsdamer Straße, a heavily trafficked street associated with the flânerie surrounding theater, entertainment, nightlife, and prostitution in both prewar and contemporary Berlin. Henke invokes the specters of Potsdamer Straße’s layered histories by installing a red-tinted spotlight, whose roving light beam shines from the gallery’s former kitchen space on the appliance sculptures, the exhibition viewers, and onto the street. Conjoining domestic interiors and urban publics by imaginatively navigating across Berlin’s pasts and present, Henke’s Auf dem Asphalt botanisieren gehen subtly unearths the gendered exclusions of labor and care, that lie beneath the collective fantasies of reinhabiting shared space and returning to so-called normal life.

[1] Interbau Berlin 1957. Amtlicher Katalog der Internationalen Bauaustellung Berlin 1957, p. 14.

[2] Klaus Kemp and Keiko Ueki-Polet (ed.), Less and More: The Design Ethos of Dieter Ram (Berlin: Die Gestalten Verlag, 2009), p. 351.

[3] Silvia Federici, Wages Against Housework (Power of Women Collective and Falling Wall Press, 1975), p. 4.

[4] Klaus Kemp. Dieter Rams. Werkverzeichnis (Berlin: Phaidon Verlag, 2020).

[5] Walter Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, Vol. I.2 (Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1983), p. 5

Carlos Kong