Archive

2022

KubaParis

bone-marrow

Location

fiebach, minningerDate

18.03 –29.04.2022Photography

Mareike TochaText

carry all in one

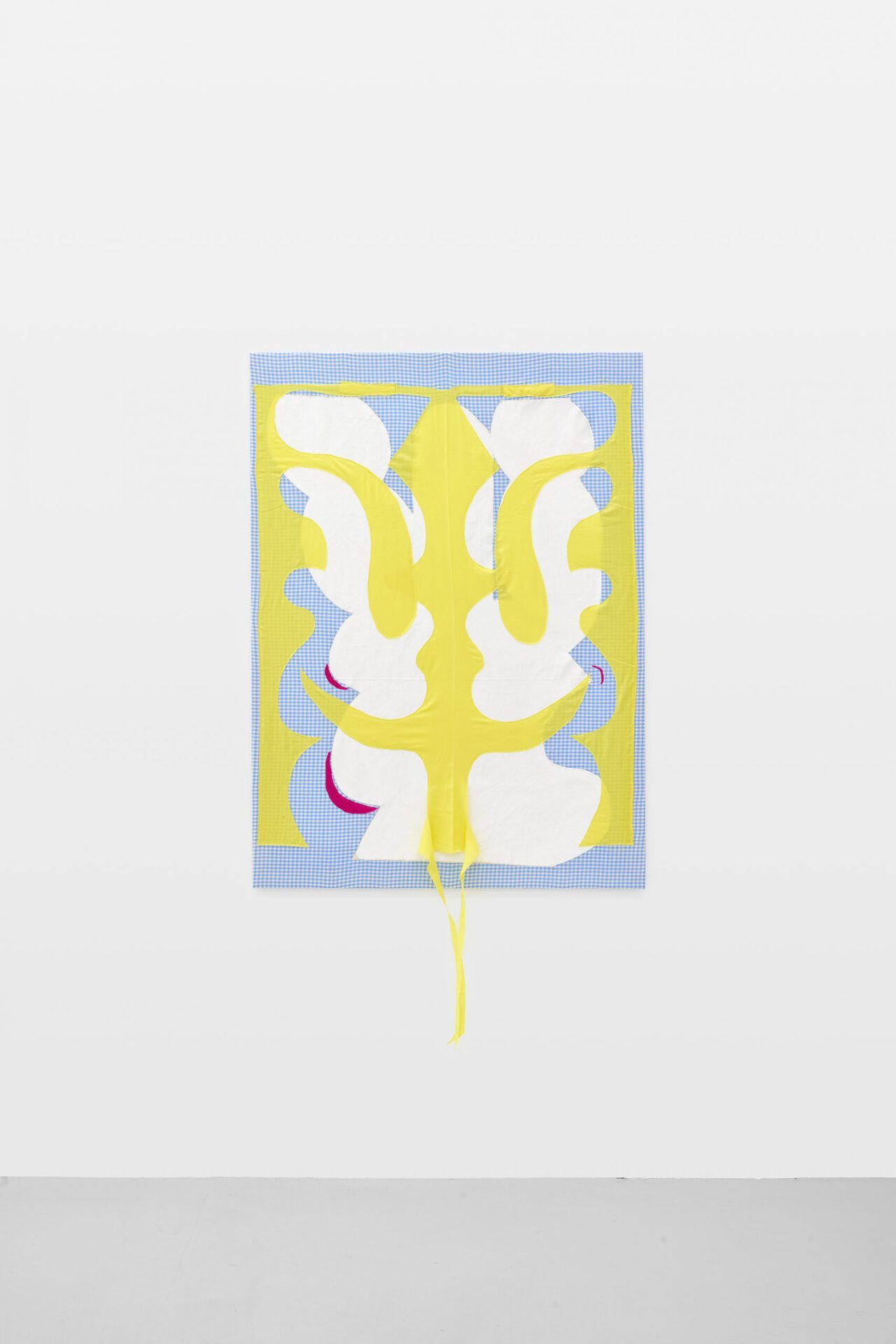

“Before the tool that forces energy outward, we made the tool that brings energy home,” writes American science fiction author Ursula K. Le Guin in her book The Carrier Bag Theory Of Fiction. There, she lays out her visionary approach that reframes the history of human technology as one of the cultural carrier bag rather than a weapon of domination. She describes containers as the great achievement of earlier gatherers for assuring collective subsistence and contrasts this with the predominance of sticks, swords and hard and sharpened killing tools associated with the ubiquitous depictions of primarily “masculine” heroism.1 Franca Scholz’s textile works sprawl across the walls of fiebach, minninger gallery in line with Le Guin’s approach to the house as the central location where energies are deposited—constantly enriched by a physical and virtual transfer in a state of perpetual change.

Individual cloth fragments carry and collect narratives, showing open and closed ends through seams and framings that are conspicuously absent or underscored through repetition.

Sewn in various layers, the quilts use colorful crocheted blankets, lace and plaid handkerchiefs, valances, curtains, fragmented and intact dish rags, and canvas and paint as equal substrates. Despite the fragility and fragmentation implicit in this process, they accumulate into a dense space that permits no hierarchies between materials, individual patches, or forms.

The exhibition's title, Bone Marrow, alludes to the tensions and interdependencies between interior and exterior, shell and filling, the larger enveloping realm and the smaller inner realm: a tissue that is connected from the inside out, like bone marrow as the connective or stem cell tissue in the bone. Franca Scholz’s visual objects are also bound together from the inside out. They are strengthened by overlapping layers, stitched together and compressed into stabile objecthood.

In her essay Making Something from Nothing (Towards a Definition of Women’s “Hobby Art”), Lucy R. Lippard writes about how socially disadvantaged women design and care for their homes: “On an emotional as well as on a practical level, rehabilitation has always been women’s work. Patching, turning collars and cuffs, remaking old clothes, changing buttons, refinishing or recovering old furniture are all the traditional private resorts of the economically deprived women to give her family public dignity.” She describes the constant alteration and overdecoration of domestic space—often attributed to feminine garishness or “bad taste”—as women’s creative restlessness and speaks about how hierarchies and gendered attributions relate to the categorical distinction between fine and applied arts.2

A dense compression of domesticity unfolds across the walls in the interplay of perspectives. Does the gaze lead into or

look down on the floorplan of a house? The caricature of spatiality in which the body can barely still assert itself,

immersed in all the materiality surrounding it, indicated only by the individual, fragmented pieces of clothing, like the last shirt sleeve. Le Guin also conceives of the house as another, larger version of a pouch or bag—a container for the human body: “Finally, it’s clear that the hero does not look well in this bag. He needs a stage or a pedestal or a pinnacle. You put him in a bag and he looks like a rabbit, like a potato.” In contrast to the preposterous figure of a pocket hero, Franca Scholz’s works are characterized by a resolute tenderness and sensuality that is physically pleasing in its intimacy and narrow confinement. Two parallel hands touching (one large and protective, the other small and clawing) engender a sense of familiar intimacy between the works and their surrounding, domestic environment.

“Domestic space—as long as it is not society imposing it on women, as long as it is not prescribed to us by the patriarchy—it can be a very powerful space.”3

1 Ursula K. Le Guin: The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, 1986

2 Lucy R. Lippard: The Pink Glass Swan - Selected Feminist Essays on Art, Making Something from Nothing (Towards a Definition of Women’s “Hobby Art”), 1995

3 Deborah Levy: Ein eigenes Haus (Zitat übersetzt aus dem Deutschen), p. 104, 2021

Lisa Klosterkötter

Lisa Klosterkötter