Archive

2021

KubaParis

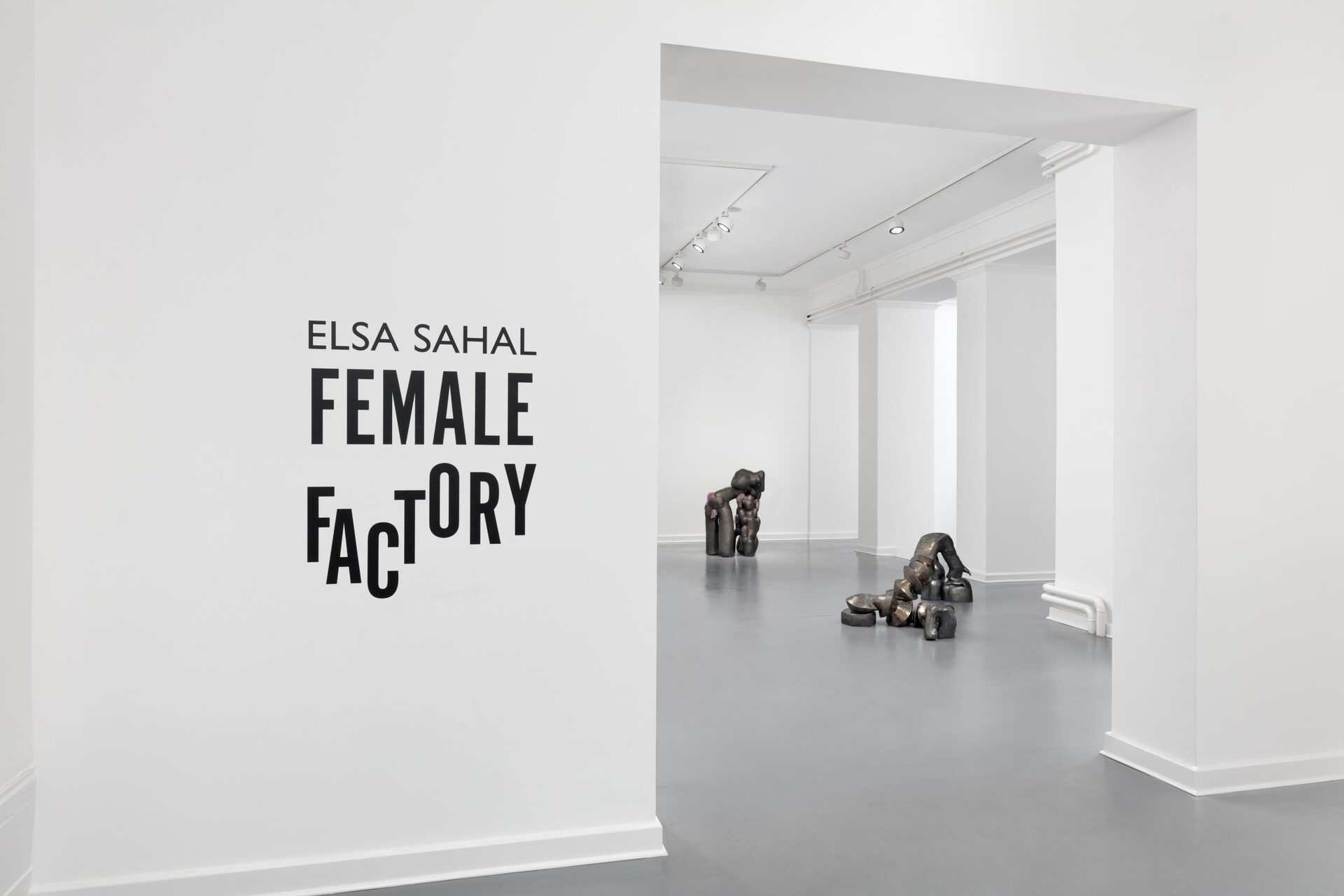

FEMALE FACTORY

Location

SETAREH BERLINDate

10.09 –05.11.2021Subheadline

SETAREH Berlin is pleased to present the first solo show by Parisian artist Elsa Sahal in Germany. Dive into Female Factory, where the clay and the flesh, the body and the ceramics become one. Sensual, obscene, bordering on the grotesque, the substance flows like lava, constantly redefined by a logic of its own. Elsa Sahal approaches the history of the sculpture, erectile because essentially male, with the gauge of feminism guided by the principles of horizontality and chaos. The nauseating malleability of bodies becomes the wellspring of new fluid corporeality: emancipated from any standard, crossed by the incandescence of their desires and the permanent excitement of an elsewhere.Text

According to Pseudo-Apollodorus, there were two rocks at the edge of a road in Panopeus

in Greece that smelled like human flesh. It was said that they were the remains of

the clay used by Prometheus to create the first humans.

The specter of these blocks of clay, ready to come to life, haunts the world of Elsa Sahal,

which is populated by ductile forms bearing the imprint of her hand, never finished,

always in a state of becoming. Growths reminiscent of viscera, masses of half-mineral,

half-organic flesh, fragments of itinerant bodies … For more than twenty years, the artist

has been tracing the analogy between clay and body that stems from mythological and

literary tales regarding the “creation of life from clay” (the golem, the god Khnum, Adam

…). For her, “the body is inseparable from this material, as if the clay was already of the

body.”

While Elsa Sahal may be re-enacting the act of creation, her work is in no way governed

by some spiritualizing intent preoccupied with a quest for sanctified origins. In fact, by

using ceramics—this domestic art form largely ignored by the history of art—Elsa Sahal

prosaically reconnects with the wretched, earthly and feminine face of the human condition,

while disassociating herself from a representation of man as a spiritual being and

the cause of an array of toxic oppressions—social, environmental, racial, and genderbased—

since the Enlightenment.

It is significant that the motif of the head is almost absent from Sahal’s oeuvre, whereas

the foot, a symbol of being anchored to the reality of the earth, constitutes a leitmotif.

Somewhere between an elephant’s foot, a horse’s hoof and a glam-rock platform shoe,

the sculpture Grand futuriste (2003) opens the exhibition with this idea in mind. The

work is inspired by a sculpture by Umberto Boccioni from 1913; centered around two

blocks, a triumphant bronze figure emerges, striding away with a sense of its own movement.

Reworked by Sahal, the figure becomes liquefied. All that remains are its buttocks,

about to be absorbed by the ground. Boccioni’s futuristic man has lost his head, literally

and figuratively, and its presence now gleams with the dark enamel of its dissolution.

Until now, the “universal” human was a man, a man that Elsa Sahal has knocked off his

pedestal. Through the use of ceramics, this medium “lower than the earth,” he is now

reduced to his role in a larger ecosystem and a porous corporality. Soft, vibrant and lively

to the eye, yet cold and hard to the touch, the artist’s ceramics are thus characterized

by their sensuality and formal ambiguity. They are redeemed by the sense of collapse

that presides over their existence, as if they have been sucked in by quicksand and the

source of their erectile sap has run dry. Erected to the glory of the patriarchy, or at anyrate dated principles, they have struggled to stand up straight and extend their power,

and their destiny has finally caught up with them: that of being symbolically castrated

(animalized/feminized/queerized), or of total collapse. “Remember, human, that you are

dust and to dust you shall return.”

Sahal’s oeuvre and its forms are in fact in accordance with the idea of a primitive chaos

that existed before the world was arranged into fixed categories. Her work establishes

an era in which a tired and toxic masculinity gives way to other forms of being in the

world. For her, a human being is neither man nor woman, but rather a spectrum leading

to a utopian new world where the binaries underpinning modern Western philosophy

(human/non-human, masculine/feminine, body/spirit, interior/exterior) are no longer

relevant.

Elsa Sahal prefers entities that are tired, lying down, and influenced by their environment

(whether this is the marine world in her Fontaine, or even baby pink, the color of girlhood

in our globalized Western culture). The sculpture, an organ in decay, metamorphoses and

reveals itself as unstable as flowing lava. The theme of the mutant body, which stretches,

produces and ejects new forms, is notably addressed in a sculpture by the artist on

the subject of maternity (Grotte généalogique, 2006).

Straddling the line between the grotesque and the violent, Elsa Sahal deconstructs the

history of modern sculpture—vertical and all-powerful, because it is essentially masculine—

through the lens of an interfering feminism guided by the principle of horizontality.

Throughout her career, she has sculpted forms evoking collapsing towers, thus destabilizing

the symbols of phallic omnipotence.

The artist inscribes herself into a conventional art history, battered and beaten to better

bend it to her desires and sense of mischief. Her sculpture of female genitalia urinating

like a man (Fontaine, 2012) is nothing more than a reimagining of the public fountain, the

symbol of a public space monopolized by men and erected in their honor. For Sahal, this

homage to modern art always flirts with a form of ironic distance, informed by the cartoonish

character of some of her works, such as Dancing Twins. Sensual, obscene and

bordering on the grotesque, the armada of buttocks and smooth breasts parodies the

male gaze (the female body as mere sexual object) as much as it appropriates its stigma

to reveal its absurdity and to turn it into a tool of pop feminist empowerment.

It is with this in mind that the Pole Dance series, begun in 2015, presents dancers in

contrast to their gamine depictions by the masters of modern art (Edgar Degas’ portrayal

of women as “frail little things,” for example). Pairs of buttocks and/or breasts

defy the gaze of the disarmed spectator. Through an ambiguity between sincerity and

criticism of the desiring gaze, Elsa Sahal distils her perverse humor into the “noble” motifs

of sculpture (the nude, the dancer, the fountain …). Beyond their farcical nature, the

nauseous malleability of the bodies creates—both on its surface and in its depths—new corporalities emancipated from all norms. The incandescence of their desires and the permanent

excitement of new horizons call for the emergence of all forms, and not some

arbitrary social, economic, genetic or sexual heritage. Phalluses, breasts, vulvas, skin and

earth form a melting pot of metamorphoses, giving tangible form to the idea of an ultraplastic

body, anchored in the earth and infinitely modifiable: a utopian body that Elsa Sahal

invites us to take hold of.