Archive

2022

KubaParis

La réforme de Pooky

Location

Friart Kunsthalle FribourgDate

18.02 –07.05.2022Curator

Paolo Baggi Nicolas brulhart et Grégory SugnauxPhotography

Guillaume PythonSubheadline

This is a joyfully chaotic exhibition of images. It brings together recent works by 19 exciting Swiss and international artists who, rather than offering a clear and transparent message, use painting to talk about the instability of our judgements, our assertions, and the confused relationships between images, the world, objects and the digital. The exhibition is curated by Paolo Baggi, Nicolas Brulhart and Grégory Sugnaux. With works by : Fabienne Audéoud, Sarah Benslimane, Elise Corpataux, Gritli Faulhaber, Sophie Gogl, Jasmine Gregory, Nanami Hori, Tom Humphreys, Marc Kokopeli, Matthew Langan-Peck, Jannis Marwitz, Sophie Reinhold, Marta Riniker-Radich, Christophe de Rohan Chabot, Thomas Sauter, Grégory Sugnaux, SoiL Thornton, Amanda del Valle, Jiajia ZhangText

The field of contemporary Western painting has always been marked by the desire for reform, proclamations aiming to ensure its continued vitality and defend its legitimacy in a given cultural era and milieu. The fuel for this approach seems today to have been watered down, to be replaced by an anything goes, the only gauge of which is relative originality. Painting no longer seems to be the nexus of conflict that it once was. Reform, then, would now seem to be no more than a token operation performed on a putative corpse, something that certain artists are taking great delight in.

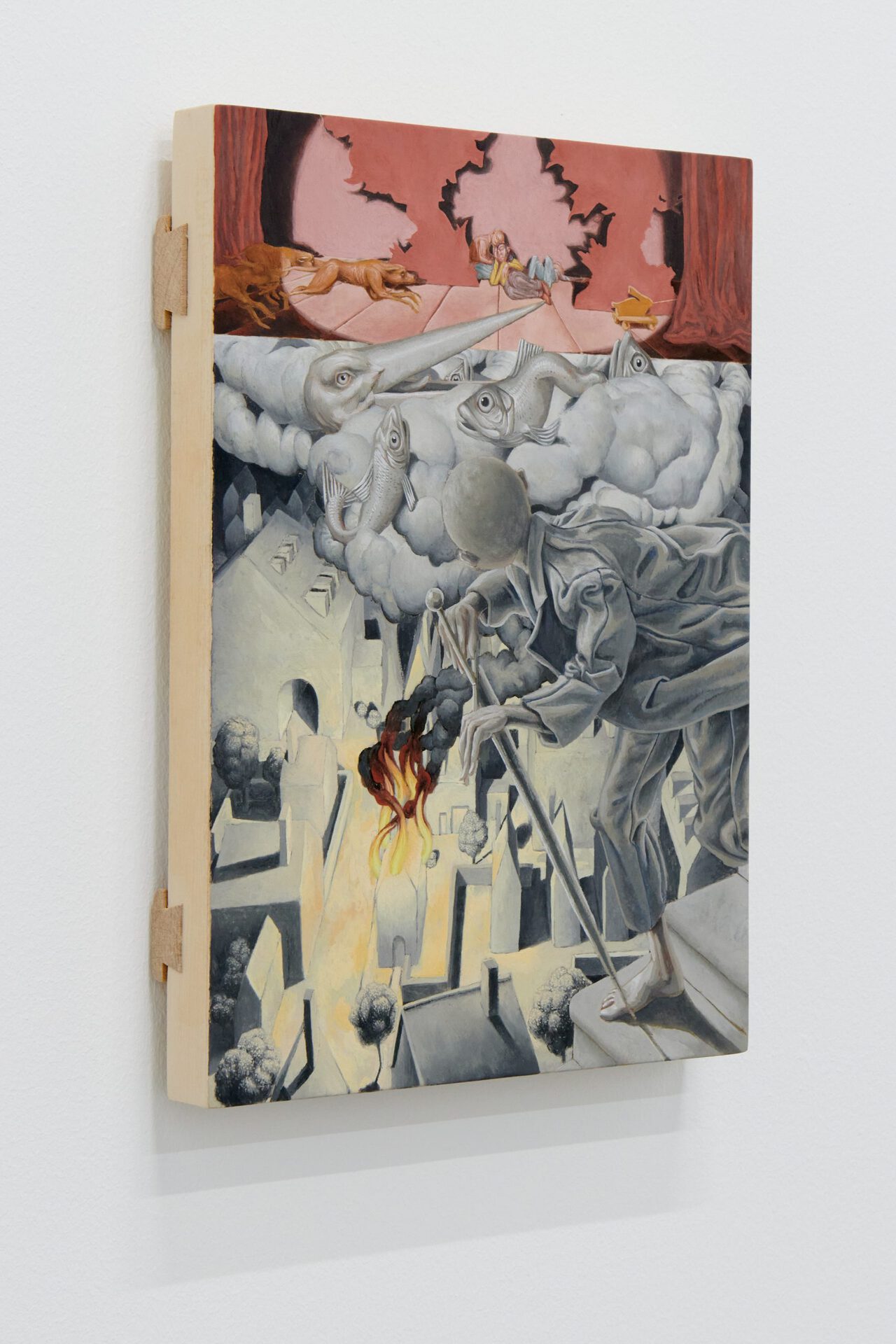

Sophie Reinhold constructs her M E N A C E through a succession of canvasses comporting a clear message. Looking more closely, their arborescent ornamentation recalls the mythical symbolism of books of old tales. This deliberately passé take announces an ambiguous morality, the threat propagated by whispering plants that gradually cover the pictorial background and the ruins. Jannis Marwitz’s painting in tempera on wood acts like a fragile icon that owes any mystical authority it may have to the adoption of certain iconographic conventions. A very meticulous observation of the work reveals aspects of a spiritual comic. Reverence for painting here is understood through a certain dose of anxiety and humour, translating the disordered reality of the medium as it is today. In Tom Humphreys’ work, black stripes on the surface bar our access to visual pleasure and the expressive dance of his brush. This partial obstruction of the modernist motif in the background signals a domesticated hand, tradition melting into the walls on which it is exhibited and contained.

The disintegration of the institutional space held by painting has not, then, entirely undermined the critical potential of pictorial engagement. If painting however no longer sees itself in terms of this institutional space, it seems to be directing its focus towards something experiential in the character of its existence. Gritli Faulhaber questions this with a painting that has been cleaved open in the manner of a book placed flat on a table. Two re- gisters, one expressive (with respect to the emergence of the image) and the other diagrammatic (regarding the conditions of perception) come together stylistically but short-circuit each other intellectually. Thomas Sauter’s abstraction presents a fauvist vitality, lending it directness and depth. The painting arranges a forest of signs that question the locus of emergence from representation and the visual and spatial conditions of this process.

In the anarchic inflation of the digital, each image is the reflection of another, exchanged, salvaged, digested and then regurgitated, streamed out at the other end of the network. La réforme de Pooky acknowledges this confusion in which gestures, colours, signs are deformed from one work to another. In this pictorial imbroglio, artists adopt a series of contradictory attitudes. Elise Corpataux’s canvas feigns to anchor itself in a specific place in order to influence us as to its provenance. Its authenticity is however generic and only goes to strengthen its potential for appropriation and dissemination. The artists thus give their attention to what is happening outside the paintings themselves, becoming part of an ubercoded imagery and gesture. Amanda del Valle’s drawings are linked by chains as kawaii as they are masochistic, infusing the life of images that are cute but raw, inoffensive but violent. The bodies of dysmorphic creations with their Japanese aesthetic become a global phenomenon, erotic inflations that stare back at the observer, mirroring said observer’s never-innocent gaze.

A comparable opposition structures Marta Riniker-Radich’s drawings, in which a meticulous and attentive technique contrasts with the activity of figures engaged with an apparatus of sensorial isolation, accentuating the production imperative, the injunction to an economy of the self or even a productive rest. This isolation of the subject is echoed in the bird personified by Sophie Gogl trapped in a selfie loop. Set against a blurred background, its body becomes the body of the image, the phone screen a painting within a painting. A comical way of creating autonomous and ridiculous beings, which, alone, are able to act. Grégory Sugnaux extracts a haunted image from this play of observations, dark, obsessive, become a phenomenon of internet forums that take certain aspects of a video game and make them part of a real community. These corporeal and chromatic deformations in gouache create a conscious image in which the harlequin figure seems haunted by us, rather than the other way round.

Confronted with the various rationales of image creation that structure identities, painting, on the other hand, aims to place us within the world as we know it, to make us think in a situated way, taking aesthetic encounters as our starting point. Jasmine Gregory’s dog poses in a hyper-theatrical manner, conscious that it is the central subject of a representation borrowing from the iconographic codes of portraiture. Other symbolic elements (Botticelli’s shell, Cézanne’s red apple) reference the broad expanse of Western (and almost exclusively white) painting, blurring its discourse in a humorous, grating assembly. Sarah Benslimane also integrates formal conventions from a popularised perspective on the history of art, which she places under her withering gaze. Her imposing painting made up of areas of flat, acidic, lacquered colour takes an artificial scopic, plastic technique to its logical conclusion, an objectivity shattered by roller coaster expressivity.

A previously unknown sensation is born out of our consumption of images: compressed proximity numbs the spirit. Various works comment on this dull anaesthetising flattening. Marc Kokopeli’s video (screening room) has a new take on the wall, the classic motif of modern painting, in order to hinder our view of a seventeen-hour documentary on the heroic history of New York and New Yorkers. The work hijacks the narration of a collective myth that provides a foundation stone for the construction of cultural capitals, in order to dilute it as part of a frustrated audio-visual experience. In the video by Jiajia Zhang, sound and image enter into a chassé-croisé that insists on our projection- and desire-inducing readings of images and the words that dub them. While the voice of cultural theoretician Lauren Berlant evokes the importance of freeing oneself from the object, the poetic movements of the camera seek out that which is outside of the picture, the indiscriminate imagery of a reified reality in which the emotions are regulated by a globalised transactional infrastructure. This transitivity is echoed in Christophe de Rohan Chabot’s work shaped by an experience of consumption that joyously drags aesthetic minimalism into the era of semiotic capitalism. A pixelated representation is founded in harsh rawness, an already capitulating NFT returned to the physical world in joyous vengeance. To crown this commerce of style and recall the causal links between art and gentrification, Fabienne Audéoud sets up a boutique in Friart. Each painting is put on sale at the modest price of five francs, with the sales catalogue priced at twenty francs. There are pullovers there to be snatched up too, for fifty francs a piece, opening the way to various codes of identification between the public and clothing: banal, basic, ordinary or Sloaney, all depending. The visible aspect of Labor Cont(r)act (assisted) (Friart Kunsthalle), 2022, the piece by SoiL Thornton, is reduced to a telephone number painted in aerosol on the entrance wall. The artist represented in the exhibition thus places at the centre of our attention a repressed dimension underlying the (institutional, personal or contractual) conditions of their invitation.

La réforme de Pooky serves as an umbrella for all these practices, the superpositions of which give it an elusive character, beyond that of an exhibition that promotes a certain type of painting or way of employing a medium that might tend towards art-school mannerism. At Friart, these practices are not situated within a hierarchy of taste, or within specific pictorial movements but rather within a temporal ambiance. The pop culture references in Nanami Hori come to the fore in a painting that tests their symbolic borders, a way of constructing images founded both in American comics and Japanese manga. In other words, a visual feast that invites us all to sit down to the banquet (you may as well, seeing as you have no choice), a free lunch in which any semiotic analysis occurring is to be seized on. Matthew Langen-Peck’s painted egg grasps this nodal point firmly, refusing any clear postulate in favour of the clumsy presence of an internal potential. This incomplete pictorial gesture creates an Easter egg that struggles to take on a final form, a political vulnerability that refuses to capitalise on any discourse, preferring instead a situation of cinematographic suspense, something left open, to be decrypted.

The exhibition is curated by Paolo Baggi, Nicolas Brulhart and Grégory Sugnaux.

Friart Kunsthalle Fribourg