Archive

2022

KubaParis

from-the-depths-of-nowhere-came-forth-a-hollow-voice

Location

La FelceDate

30.03 –13.04.2022Curator

Amelie Gappa & Lea LahrPhotography

Thomas LambertzSubheadline

Karo Schultz, Thomas LambertzText

Since the Spatial Turn at the end of the 1980s, space has been thematized and discussed as a cultural quantity. Space is no longer recognized as a physically unchangeable fact, but as a social, dynamic structure that is produced by various factors. Thus, spatial experience shifted from a dualistic to a complex system involving the entire practical capacity of human capabilities.1 Space as an indispensable given for the perception of artistic works is thus not the only form through which space shapes. Thus, urban, political and social space is also the focus of our daily perception. The exhibition title, taken from the novella “Flatland” (1884) by Edwin A. Abbott, refers to the limits of our perception of (living) space, since “Flatland” narrates a two-dimensional world from the point of view of one of its inhabitants. The division of the novella also shows that physical space is always closely interwoven with the others. In the two-dimensional world of Flatland, power structures and patriarchy are symbolized by the geometric shapes of the characters. Space and social transformations mutually influence each other, so that space serves as a site for the exertion of power. In the second part of the novella, the protagonist "A. Square" is visited by a higher power, which makes him aware of the limitations of his own spatial perception, as a cosmos with one, three and four dimension(s) also exist. The "Stranger", also called "Sphere", forces him to question the most elementary laws of his world. The “Stranger” illustrates the limitations of the two-dimensional Flatland to him by no longer being physically present for the protagonist, but by being able to prove his presence through his voice: ”I winked once or twice to make sure that I was not dreaming. But it was no dream. For from the depths of nowhere came forth a hollow voice—close to my heart it seemed—.“2

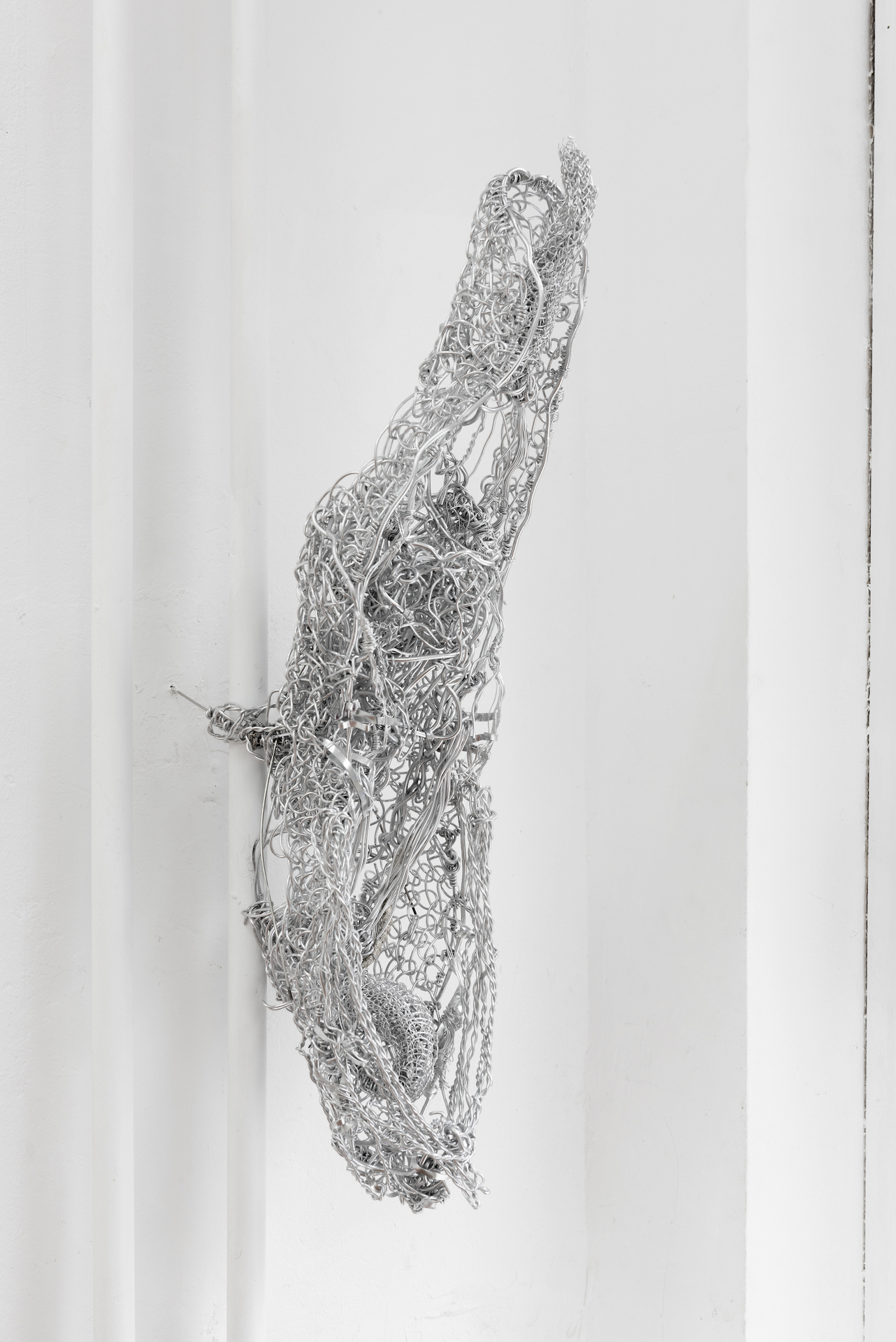

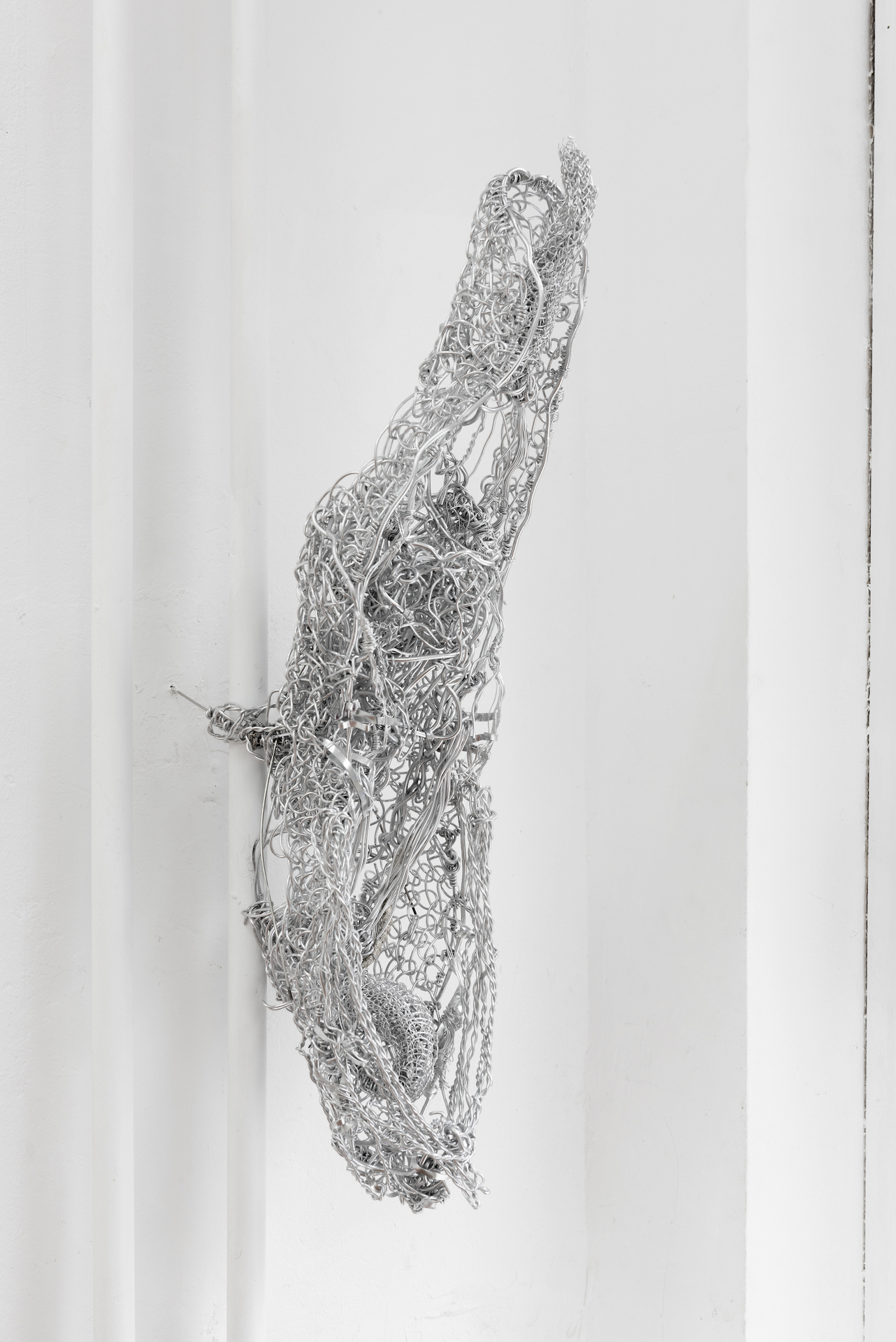

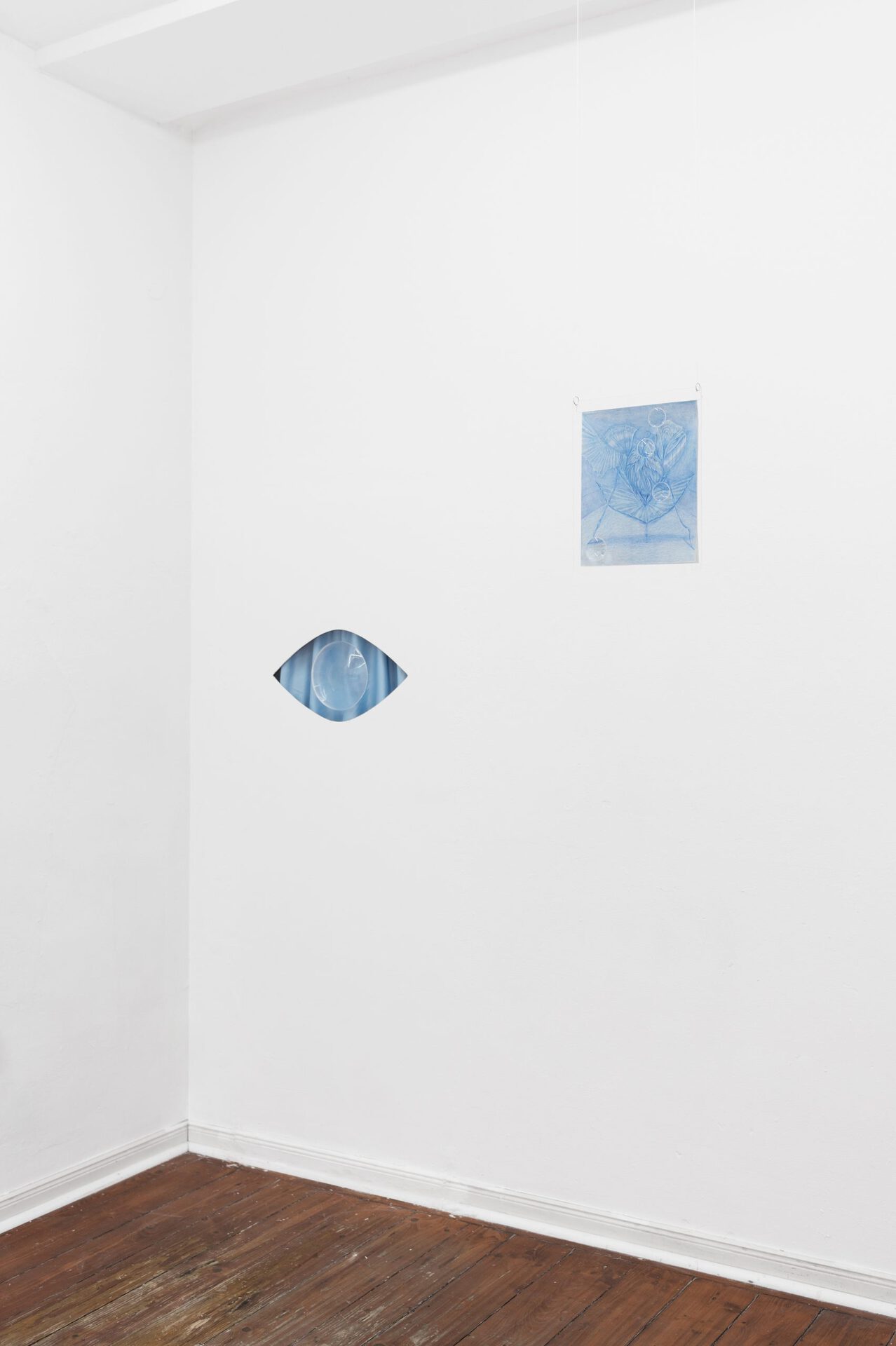

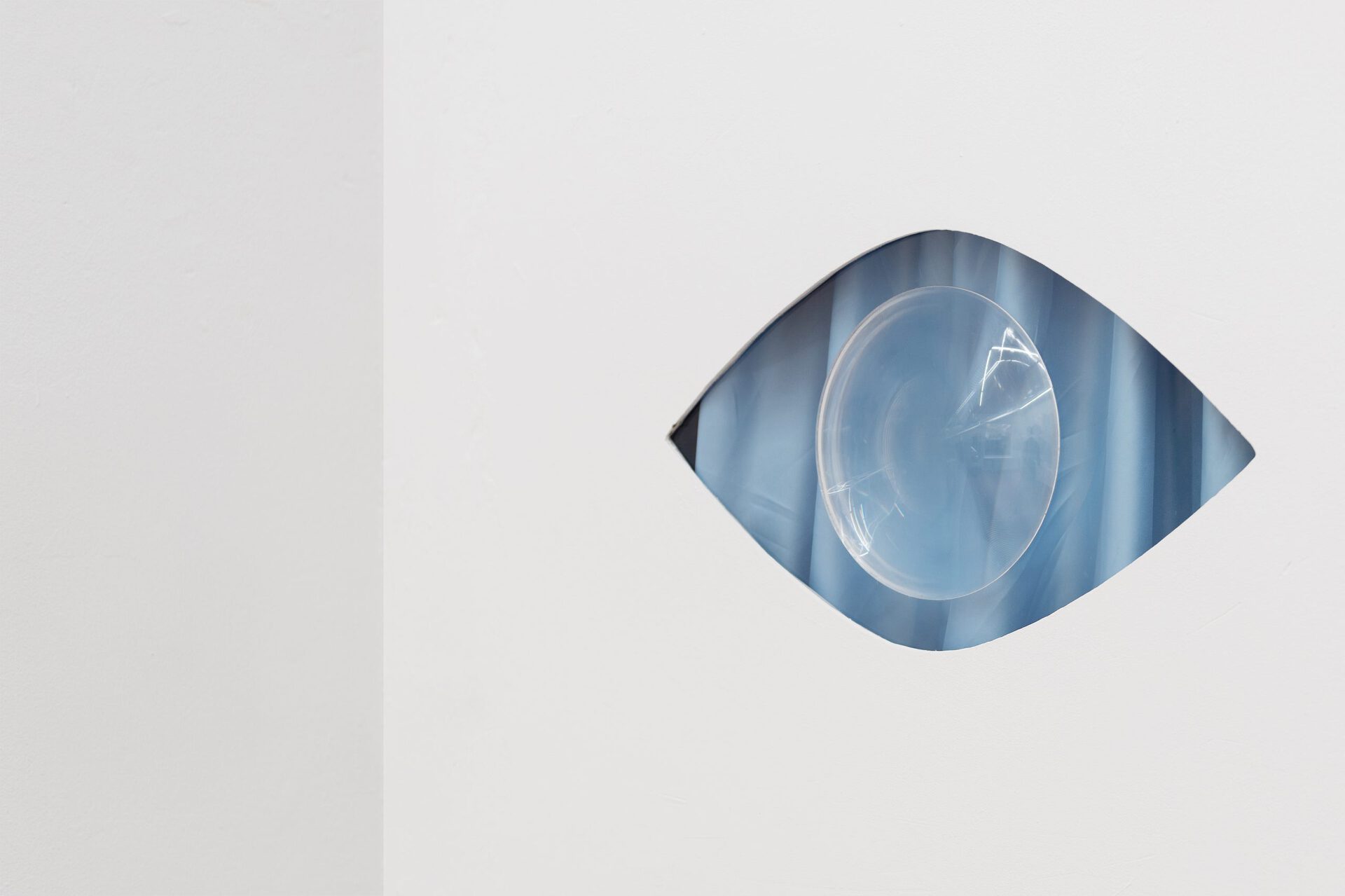

Karo Schultz often works directly with the exhibition space in her artistic expression and specifically addresses the existing structures; for example, in 2021 she showed the space-specific installation "luster groundings", which was based on the plug arrangement of the exhibition space. Karo Schultz's works shown at La Felce draw from her interest in strange, grotesque, hidden things and places. Here, the spatial confrontation and direct intervention in the exhibition space occurs through the breaking open of the door, which was hidden behind sheetrock. This renewed presence creates a possibility of communication, which is emphasized as a result of Karo Schultz's installation. In this way, it is related to Edwin A. Abbott's novel "Flatland", as a direct reference point to the missing third dimension in the two-dimensional Flatland. The artist's chimerical work uses this allegorical power of the door and plays with it by distorting perspectives on the proportions of the attached curtain behind a magnifying glass. The reflecting eye can also be recognized as an attempt at Utopia, since the mirror is "a placeless place," an "unreal, virtual space that opens up behind the surface"3 and thus makes it possible to stay in an illusionary space. At the same time, a reference to Schultz's earlier works can be seen, in which she explored the power of the portal. Since this third door leads out of the exhibition space and into back rooms unknown to the visitors, it can also be understood as a portal. Schultz's delicate wire figures not only further emphasize her interdisciplinary approach, but seem to float in space, suspending metaphysical laws. Her sculptural objects in space seem like beings that have strayed from another world into ours.

For Thomas Lambertz's works, space does not represent a direct architectural point of reference, but rather a sense of security and ultimately serves as a subjective sanctuary. His objects balance in a reciprocal relationship between defensibility and defenselessness as well as security and danger. Starting from a certain immediacy for the viewer, he stages existential moments that appear identifiable. The windows of his works create an ambiguity. The white wall marks the limitedness of the view, which contradicts the actual use of a window as an opening to the outside world, through which light and air can flow into the room. Furthermore, the view of the white wall can be understood as a contemplative moment. At the same time, the delicate imprint of the bird on the window pane highlights the brutality of its impact, as this wall could also have remained innocent. All that remains of the bird, however, are the delicate, indexical imprints. While windows are emblematic of the dialectic of inside and outside, Lambertz shows us that this is precisely what the birds fail to understand. The distinction between window and wall is difficult for them, since the windows signal exactly where they lead, namely into nothingness. Our shelters thus become places of danger for the animals. At the same time, in a Western understanding, the human shelter is preserved precisely by the deceptive windows; they allow a view into nature that is nevertheless excluded. If windows are, according to Isa Genzken, a necessity of life: "Everyone needs at least one window"4, they are always also border guards of alienation. Like Flatland, Lambertz's work refers to the limitations of our perception and the question of the extent to which it manifests our reality. The images we consume form our own reality of life5 and can thus hinder our rise out of the underground cave.6

1 Julia Burbulla, Kunstgeschichte nach dem Spatial Turn, Bielefeld 2015, p. 4.

2 Edwin A. Abbott, Flatland. An Edition with Notes and Commentary by William F. Lindgren and Thomas F. Banchoff, Cambridge University Press 2010, p. 156.

3 Michel Foucault, Of Other Spaces, Utopias and Heterotopias, 1967, in: Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité, 1984.

4 Isa Genzken, “Jeder braucht mindestens ein Fenster”, Köln 1992. – Translated from German.

5 See also: Emma Donoghue, Room, 2010.

6 See also: Platons allegory of the cave.

Amelie Gappa & Lea Lahr