Archive

2022

KubaParis

Hennissement

Location

Centre PasquartDate

27.01 –26.03.2022Curator

Felicity LunnPhotography

Guadalupe RuizSubheadline

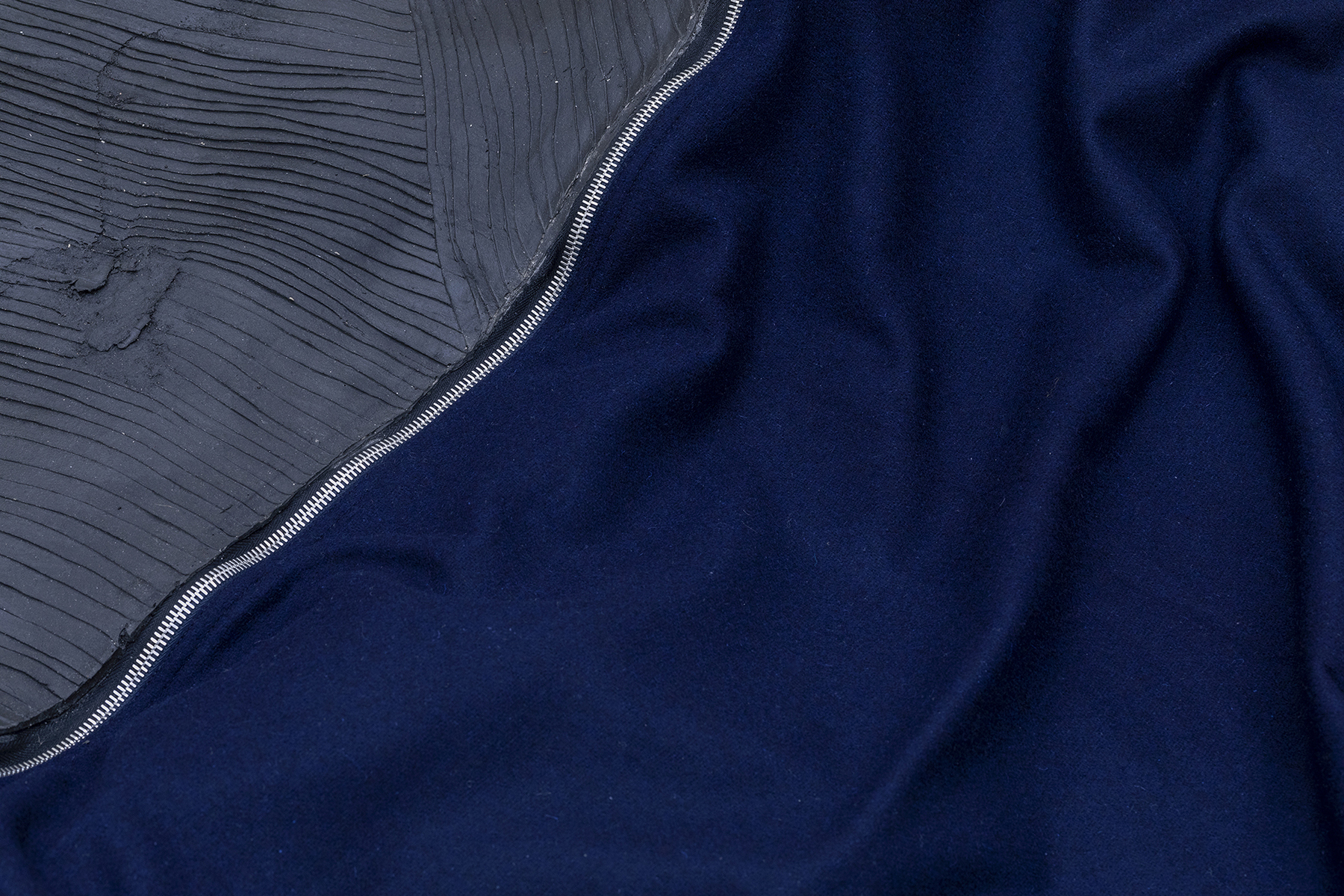

The narratives of Gil Pellaton (*1982, CH, Biel) are about strange, fragmentary occurrences. For his objects and installations, he often uses organic materials such as tiger balm and coriander or a mixture of turmeric and bone glue. Their effect unfolds not only visually, but also through specific smells and their haptics. Pellaton’s independent artistic vocabulary is inspired by cultural history as well as the symbolic charge of the materials and their reinterpretation in the art context. Hennissement is the continuation of an ongoing work that seeks to develop a universe independent of the prevailing frames of reference. The deliciously mysterious works develop narratives that remain incomplete and open up a world of poetry in which feelings can improvise endlessly. It is the artist’s attempt to invent a language without words and concepts, where yapping, neighing and barking form our new grammar. The exhibition shows existing works as well as several new ones inspired by the dialogue between the artist and the author Elise Lammer. In addition, a poetic text has been created for the accompanying publication, which is at the same time inseparably linked to the exhibition concept.Text

This is where it all starts to make sense

I guess like many, we had the ambition to write the most beautiful text to accompany this exhibition. The beauty of this text would be found within its use-value: it would function as a shield and garner protection against all dull interpretation.

We hoped, and failed at writing the second most beautiful incipit (after Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Hundred Years of Solitude).

We lacked tools. And wrote many versions.

Words—our tools—, were so binary. We knew that we didn’t know what this text would be about, since “being about something” was the sad faith of the literary and artistic works that had left us hopeless. How could we claim space without being authoritarian? Could our presence exist via a hiatus?

We did, however, agree on one thing: art as world-making.

For weeks we orbited around our feelings like hawks circling their prey.

And finally, it became clear: This was no longer a text, it was a Membrane. And this is where it all starts to make sense.

The Membrane appears when meaning is reversed, or rather re-mixed, but with no particular order.

The Membrane is the liquid that flows between the lines of mistranslation; it’s the omniscient narrator holding a secret; the lucid minute of our amnesia-stricken hero. With shaky handwriting, a last note left on the kitchen table reads: ”it never made sense anyway”.

The Membrane is a mirror that no longer reflects faces, but only light.

The Membrane is the elated feeling that you get when you have reached the top of the mountain, after an almost sleepless 48h-hour hike, but the only thing you see is fog. It is the trust that you’ve reached, at the cost of exhaustion, the only spot on Earth from where one can usually see two oceans.

An anti-fascist version of Duchamps’s Inframince, the Membrane is the abstract physicality that you feel when entering a room where some instants ago people were making love.

The Membrane is the grease left by your fingers on the paper you’re holding while reading these lines.

The Membrane is that impeccable blur you get when wearing your myopic friend’s prescription glasses. When slopes become stairs.

The apparent randomness of the effects triggered by The Membrane feels chaotic, yet with the dominant reference system melting away, a world of aimless poetry appears underneath fear and solitude.

***

Stripped of predetermined meaning, and adorned with the glitzy Membrane, art (Art! Art!) started appearing under a new light.

The exhibition, conceived like a scale model of the Tower of Babel, could be the locus of our world-making. We hoped that the Membrane would provide guidance, —or rather misguidance—, through this three-dimensional space, which sheltered so many odd objects. The exhibition as means not as an end: like the isolated chapter of a book that was never written, erected as an altar made of thousands of blank pages. In this version, each work, once combined with any other work, would form an ungraspable constellation of slimy, yet delightful confusion.

And yet, when the fog settled on Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim, and when, washed by water particles from two evaporating oceans, institutions of divine proportions unveiled their true purpose, all that spiraled knowledge that had patiently been accumulated wasn’t any longer of any help: itchy arms, sore throat, slight nausea, an inexorable need to check our phones. So we dismissed the exhibition and ran to a nearby park to watch birds spiraling into the blinding midday sky.

We also attempted to write a dialogue for the most unspectacular, the less dramatic episode in our lives. The second or third most beautiful dialogue (after Robbe-Grillet’s Eden and After) was equally pretentious and cryptic. Boredom had been replaced with affect; what was meant was never said and vice versa. Imagination was the guiding principle of a fable where each protagonist was a bystander of their own life.

In one version, it was unclear if the two or three protagonists were able to hear each other, or if they were simply attempting to lip-sync their own train of thought. In this dialogue, museum shops were giving away free teapots whose shape were a scale replica of the museum itself. The public programme tasted like breast milk. Sweet water was contained in transparent limbs. We conceived the dialogue to be whispered. It clumsily evoked the thwarted perception of two or three humans’ spending a sun-drunk day on a shabby boat. Only we knew that this day would turn out to be their last. At a time when the world still lacked words to describe thoughts and concepts, the lost humans were microdosing on approximation.

“When I lay my eyes on something, the image it’s reflecting back to me scratches my retina. So I can no longer watch, I simply see. A piece of tin relentlessly polished into a dyslexic mirror, reflects our shadow-image. I’m lazily lying in the vessel’s hold, and I see you seeing me. “

“Earlier I started walking backward, laughing in slow motion, watching sound and hearing motion. We’re now cruising aimlessly. Rays of sunlight pierce through the hull of the boat, liquefying the hard surface of everything around us. The reflection is so harsh that it’s almost blinding. The Membrane makes me blink. From above as below. Let’s cruise at full speed, 22 knots until we reach the center of this body of water. I want us to see and be seen. “

“The sun-burnt skin of our 5-m long motorboat bears some light scratches. The black blades of the white-cased Yamaha propeller are now slowly melting. I still can’t see the two oceans, but they are right here, their incantatory presence as proof of existence.”

[almost imperceptible] :

“I remember once dipping my fingers into a lukewarm, gooey, texture. I once read that “a gentle massage of around 5cm a second, with a force of about 1 gram is ideal for the active substances to be released into the skin”, so I allowed the viscous stuff to stick between my thumb and my index finger. I close my eyes, and try to resist the urge to smell the very strong scent of camphor and menthol.”

Once we failed at writing this dialogue, we thought about dyslexia, and autism, and hoped that the exhibition-shelter could elevate such conditions to gifts: every image would claim confusion; every object would aim for disorientation. Triggering distraction, the Membrane had scrambled speech, helping us realise that the dialogue was no longer relevant. So we muted the protagonists.

In another version, the exhibition-shelter celebrated art as an instrument of ritual. Free of power taxonomies, of consented semiotic and symbolic loads, each object on display was in fact a white page. The spectrum was our shelter. Hiding in the forts we had built with wooly blankets and shabby chairs, we pointed our fingers pointed towards the sun and air-traced the figures of two horses. Our earliest experience of art was incantatory and magical.

Like the geriatrics millennials we were, we praised Marxism and anarchy, yet we only remotely had witnessed such concepts in the pages of press releases written by unapologetically perfect curators. It left us clueless. A mind-bending gaggle of words that, over generations of mistranslations—back and forth between the oceans—the blacked-out pages had lost all connexion to meaning. So we burnt the press release.

But what tools other than words and institutions did we have left? We tried to convert the ashes of this text into the recording of panting sounds. In that version, we had entered the room some instants earlier, only to find the exhibition in total darkness and some particles of love still floating in the air.

Coming straight of a crisis, we wanted to share completely irrelevant details. Distract ourselves from distraction, and shelter our feelings within the forts of our disappearing trust. Among our fellow horses, the promise of change was met with particular skepticism, so they went back to their old routines as fast as a bad metaphor disappears into thin air. At first disappointed, we soon learned to appreciate that this rather was a promising symptom of anarchy.

What about Marxism? For us self-emancipation involved being cautious with the -isms, as well as with adjectives such as “hybrid” or “epistolary”, and anything branded Balenciaga, (piss off cynicism!).

So we proceeded to ban the isms.

Let’s try one last time. Though the whole project felt nebulous, we agreed on something else, besides world-making. Art (Art!) still was the apparatus of our revolution, and the Membrane its locus. And one of the things that made art Art was when it truly felt out of place, even when one could easily recognise all the string-pulling machinery behind it. In this final version, we wondered how to keep that naive, inconsistent, and warm feeling alive? After muting, banning, and burning the last remnants of institutions of any kind, we were left with an oral, pyromaniac tradition of knowledge transmission. But making world was not only about shifting, banning and re-contextualising. After all, a horse can’t be cynical.

Finally, once meaning had almost completely been abolished, our feelings could endlessly improvise. As we slowly became acquainted with the lower frequencies of a life lived as marginals, from the ashes of our memory we re-built the forts of our infancy. We invented a language without words and concepts, freed of hegemonic order. Yelps, whinnies, and barks formed our new grammar. Those were the shelters, where we, the Horses, could finally lead our quiet revolution.

This is where it all starts to make sense.

Elise Lammer