Archive

2022

KubaParis

Love Game

Location

Kendall Koppe, GlasgowDate

04.03 –08.04.2022Photography

Sean Patrick CampbellText

To Hold To Love

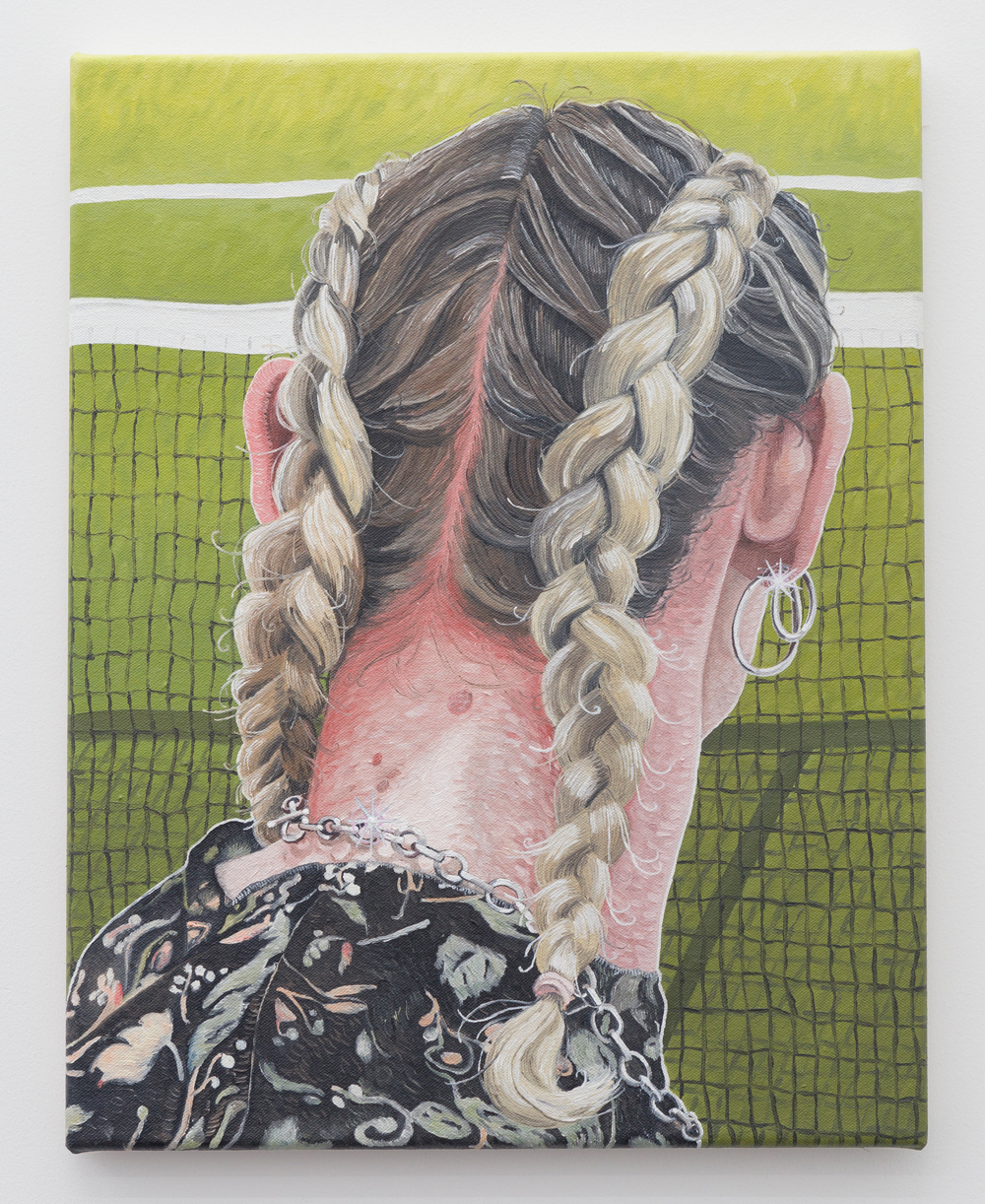

When I was a child, I was forced to sit at the feet of our next door neighbour. She was the only mum on our street that could plait hair and in the morning I would join a queue of other long-haired kids as she dutifully laced our plaits. It was a community concern that the hair was tied up, out of the way and ready for the day. On the way to school we would coo over each other, not fully understanding what was happening on the backs of our heads despite desperately trying to feel it out, our fingers poking into the gaps made in the woven-together hair, exposing frayed ends. We began shoving in slides and ribbons stolen from older siblings as soon as we were round the corner, evolving into individuals.

When I got older the responsibility of my hair became my own. This was a monumental moment and it arrived at the sweet spot where I was preparing for the first time to use my body and my style to say something about myself, but also just before I could fully understand the prejudices people could launch at you just by looking. A small autonomous time zone filled with flourish.

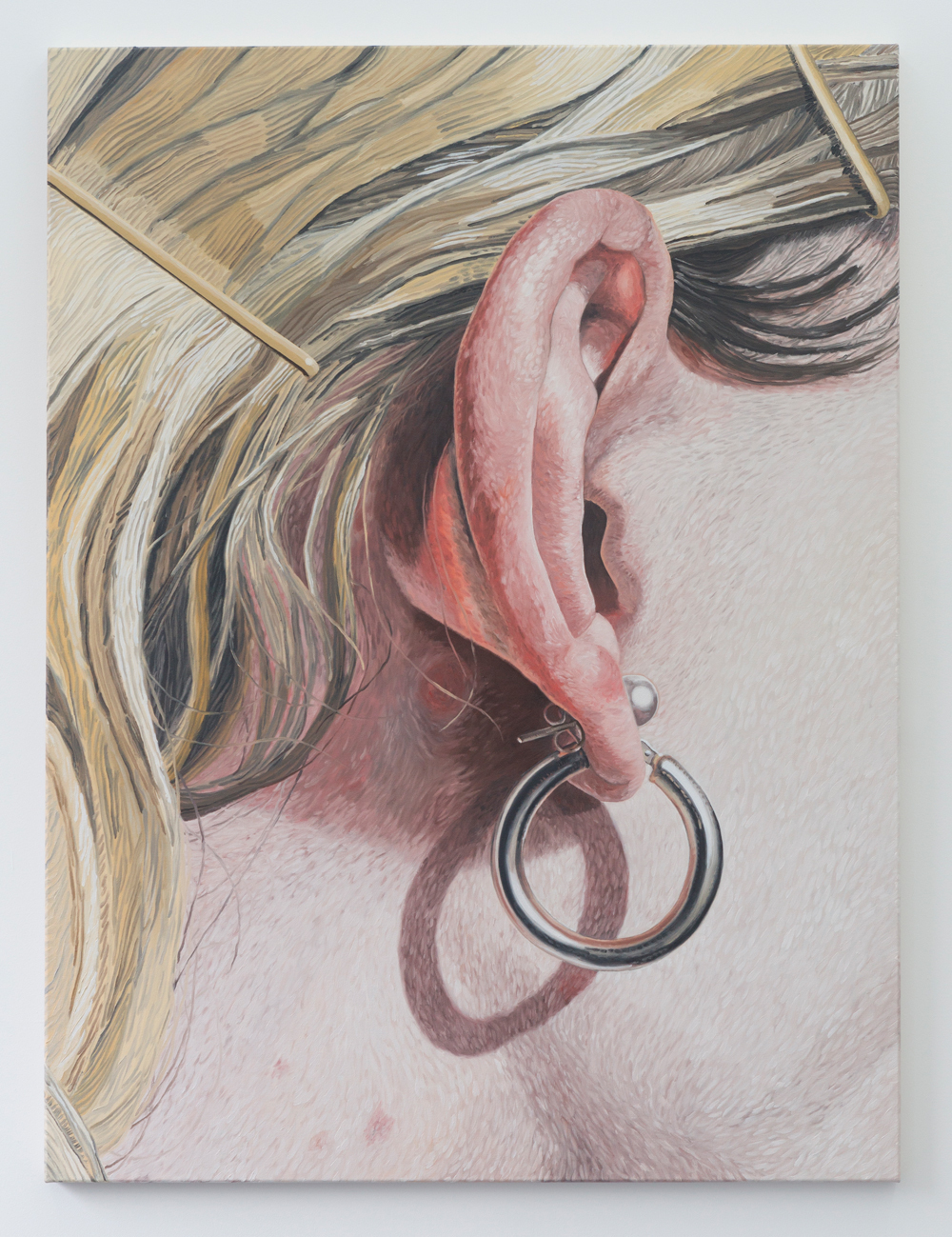

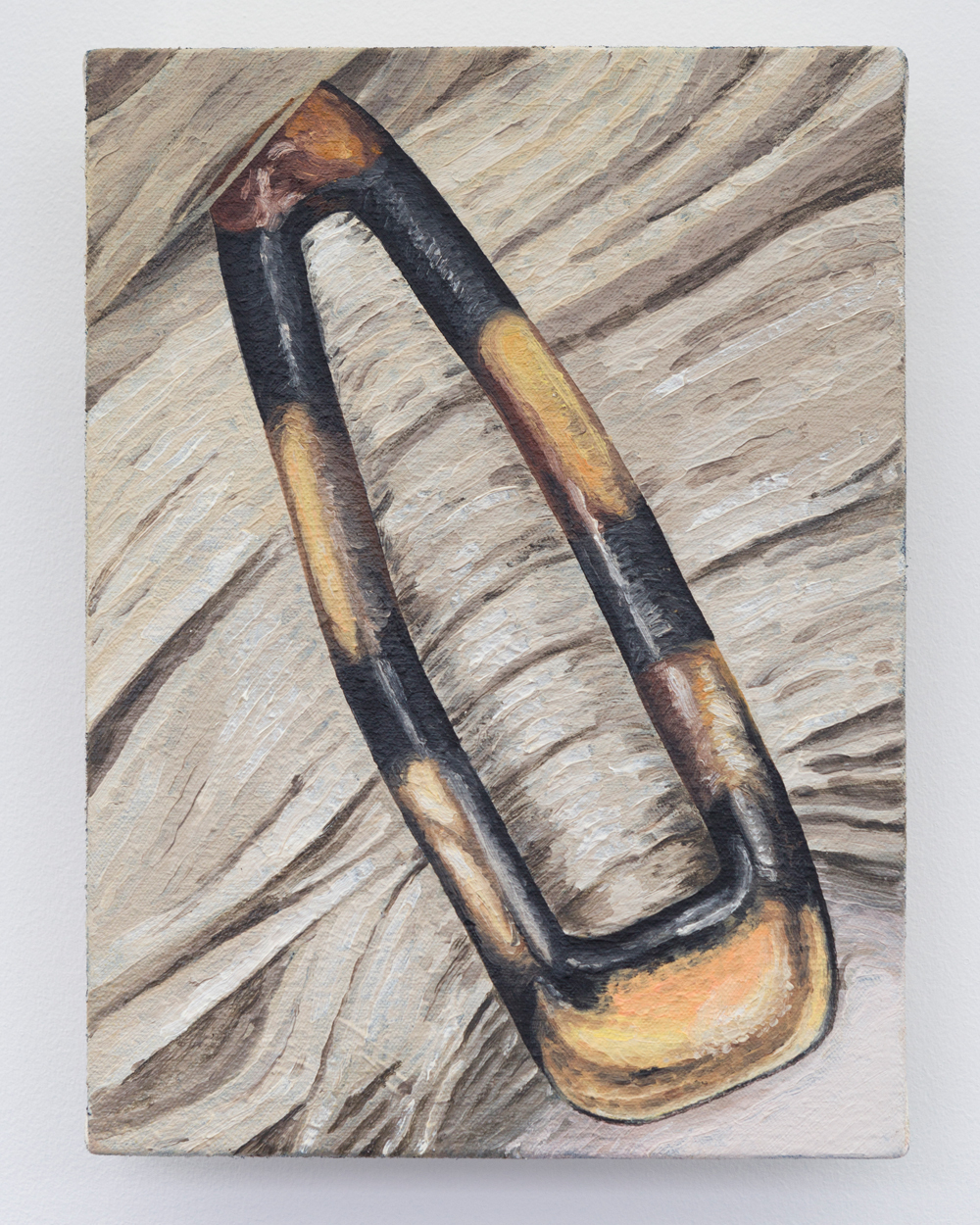

An earring, a necklace, a belt; these objects are all murmurs of the self. Whispers of breathy glamour that rupture the way we read a person, a body. These moments are the ones that a stranger's eyes rest upon when they sit opposite you in a cafe, or when you nearly walk into one another in the street.

Earrings are the sweetest of these companions. They dangle around in our skin, slipping through holes in our body. The sound of a jangling earring becomes an ally for the day, a soundtrack of comfort in our own choices.

There can be occasions though where this sound interferes with the hyper-listening we are forced to do, the sonar we employ for threats and disturbance. These threats, often quiet, born from whispers, so many of us key into as we move around day-to-day. The threats we try to imagine when we roll these objects around in our palm in the morning, still at home, trying to negotiate our threshold for the day. What does this clip activate in others, what does it perform in the orbit of this outfit? Will the sun glint off this necklace warm, as pleased to see it as I am? Or will it be too visible, the sun heating the metal so a burn sears the skin?

When we get ready, we get ready for ourselves and others, we get ready to respond and to be seen.

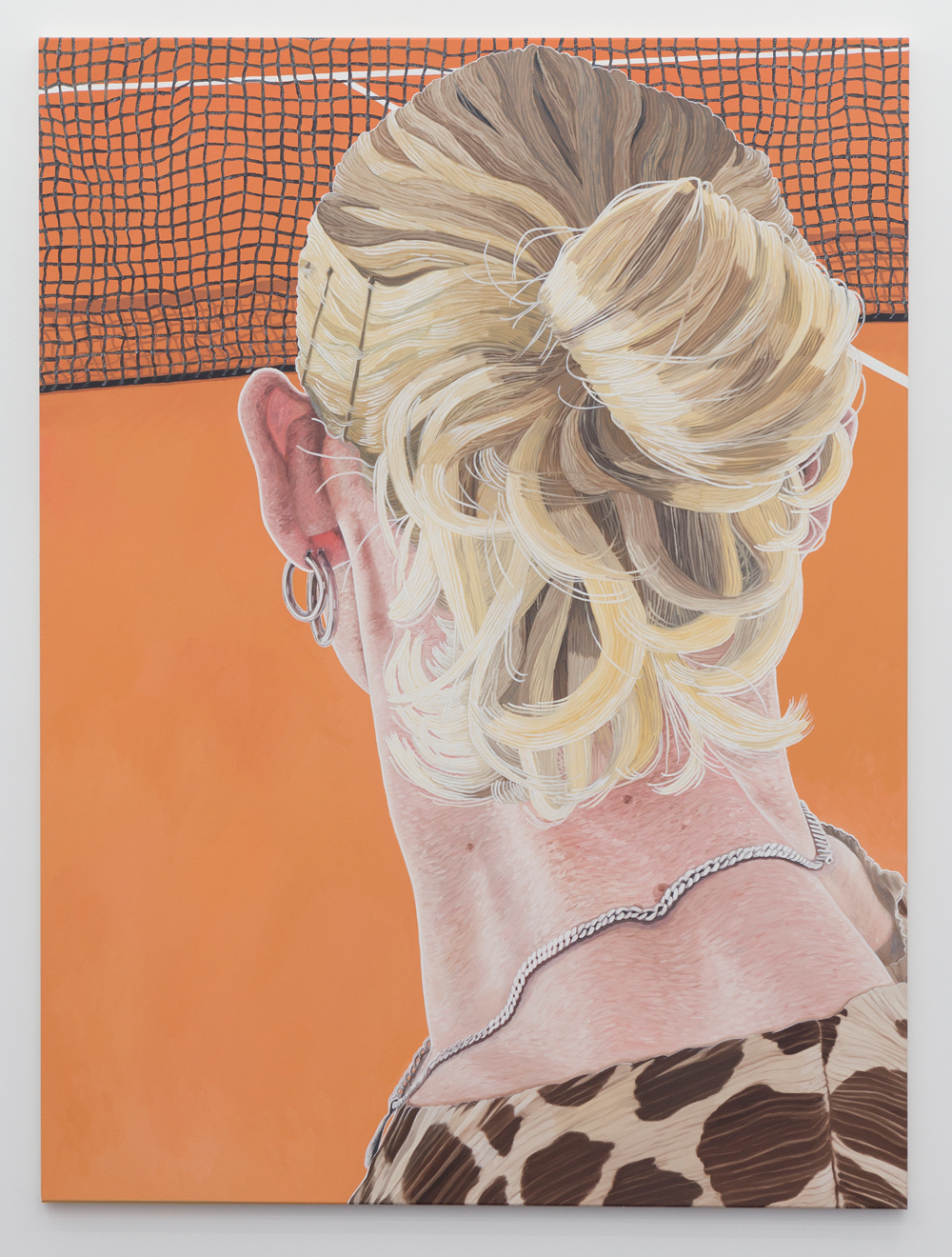

The paintings in Hamish Chapman’s Love Game reject some of the potential for such gazes. You will never be allowed to place the face of the figure in them into the catalogue of faces you have known. Nor will you ever be allowed to see the face framed by these small glamours. You are resigned to a moment, post the turn of the head, where the figure surveys a landscape of tennis courts, perhaps preparing for the first serve in a match or evaluating the next play. The glint of an earring is all we have to signify a character and it is given to us solely as a proposal.

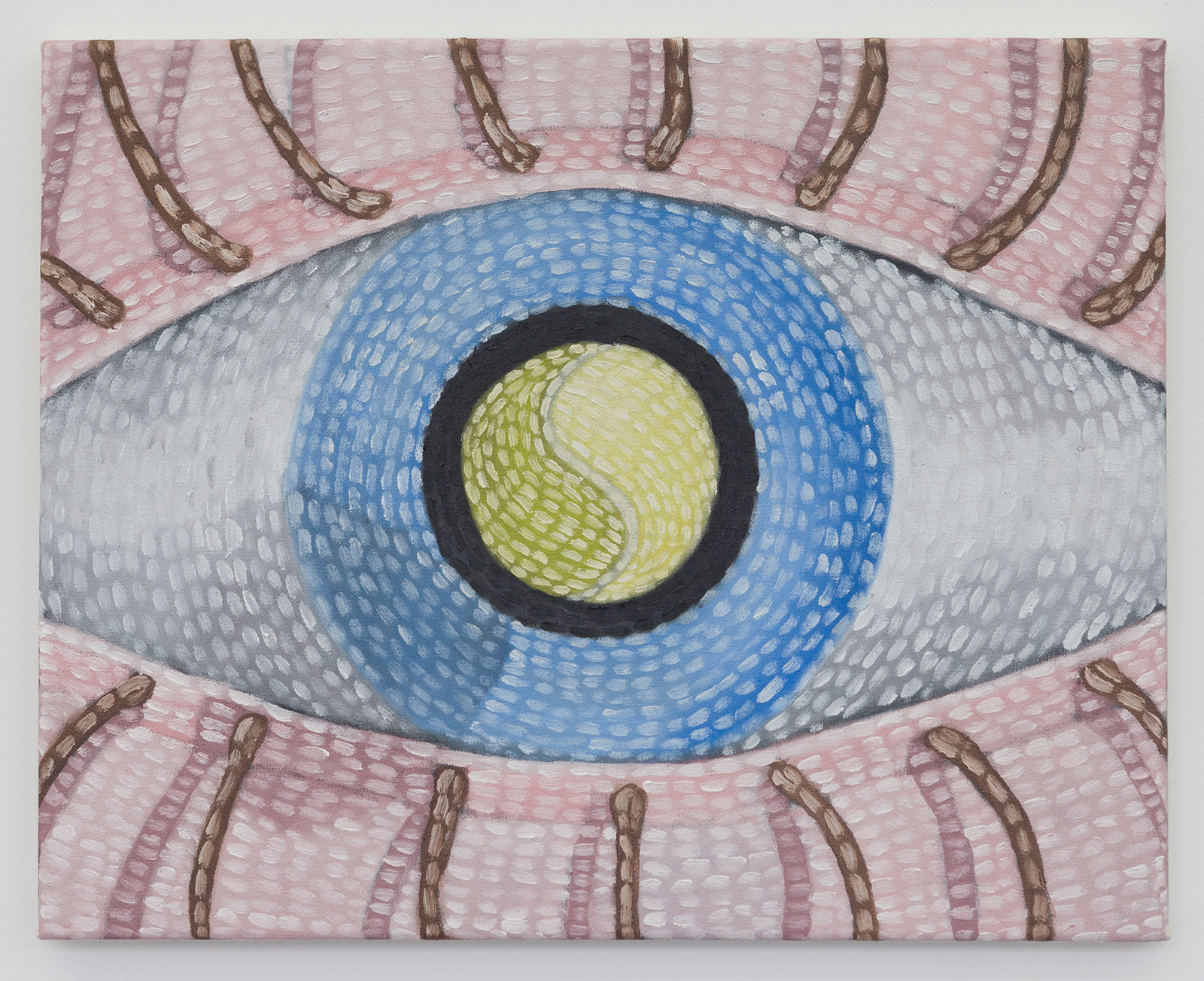

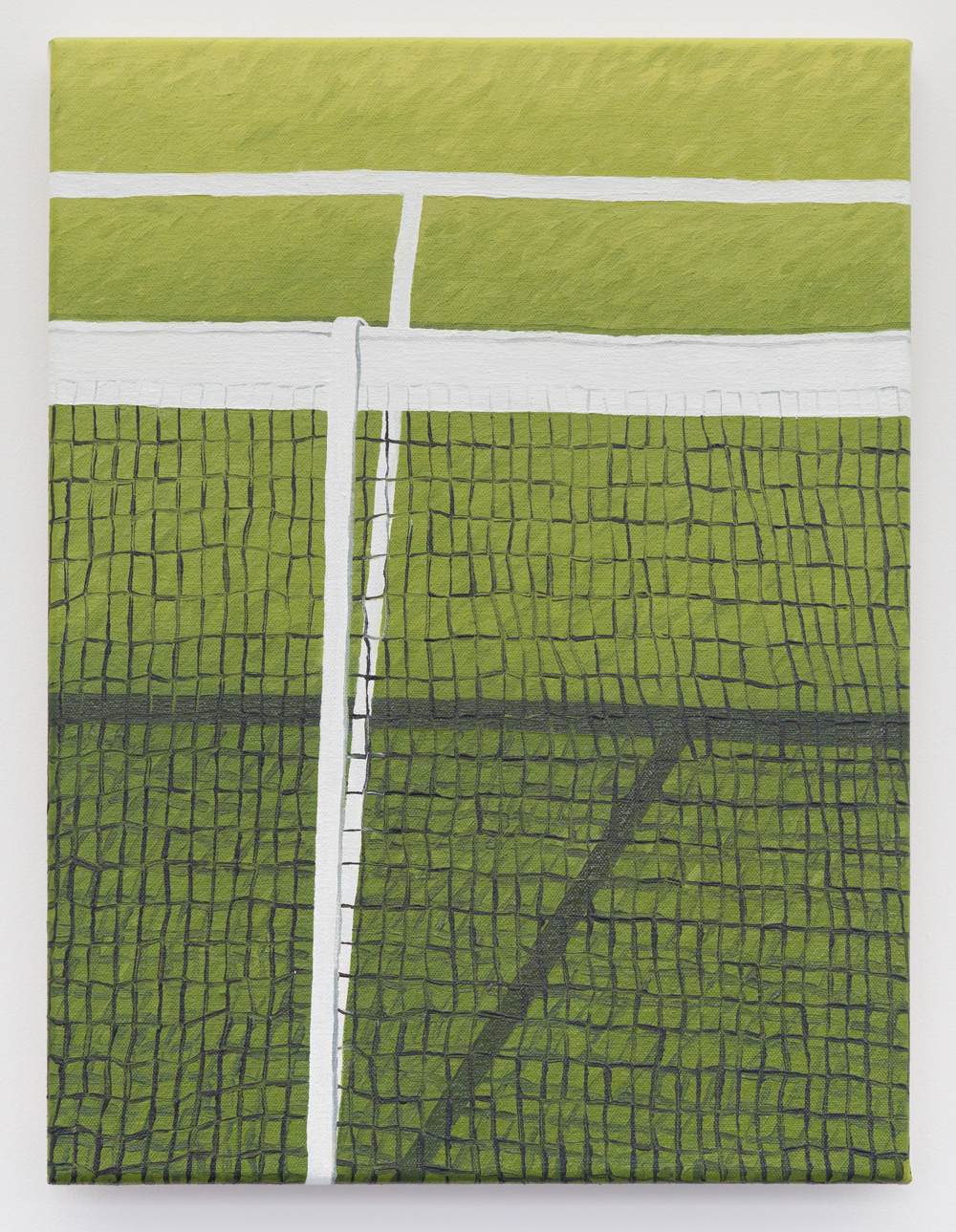

Tennis is a game of psychology, boundaries, and force. Every court is the same size and has the same outs and ins. Even with constant back and forth of balls it’s lines and boundaries stay firm. Eyes sliding to and fro horizontally, courts thudded by firm legs and certain footsteps.

Chapman’s work focuses on the court as a space for possibilities, for performing, thinking, tactics. Constants are only constants if they can stay the same when things around them change. These spaces hold form when faced with the realities of our current world or when they are inserted into Chapman’s paintings. In Bun, Hoops and Pleats (30.05.21, 14:03) we are offered the possibilities of these courts existing in the multidimensional potentials of a transformative queer future. The hyper colour of this place invites us to step onto the court and experience a game with new parameters. The net becomes a focus in the works, its role for trapping, getting stuck, in opposition to its role as a boundary and protector. Its woven threads pull through lines of texture across the canvases.

I am someone whose body has always stood them at the edge of their gender definition and because of this my hair is very significant to me. How I put it together, how I style it, using it to find and reveal part of myself. The hair in Chapman's work understands this need. In the paintings, strands of hair are tamed, gently smoothed and directed. You can feel each action in the tip of your own fingers, the anxious fumbling of a kirby grip or the dexterous movements required when plaiting hair. Clipping it up to expose the ear and give air to the small pressure points made in the skin where an earring has been rubbing in the heat of the day.

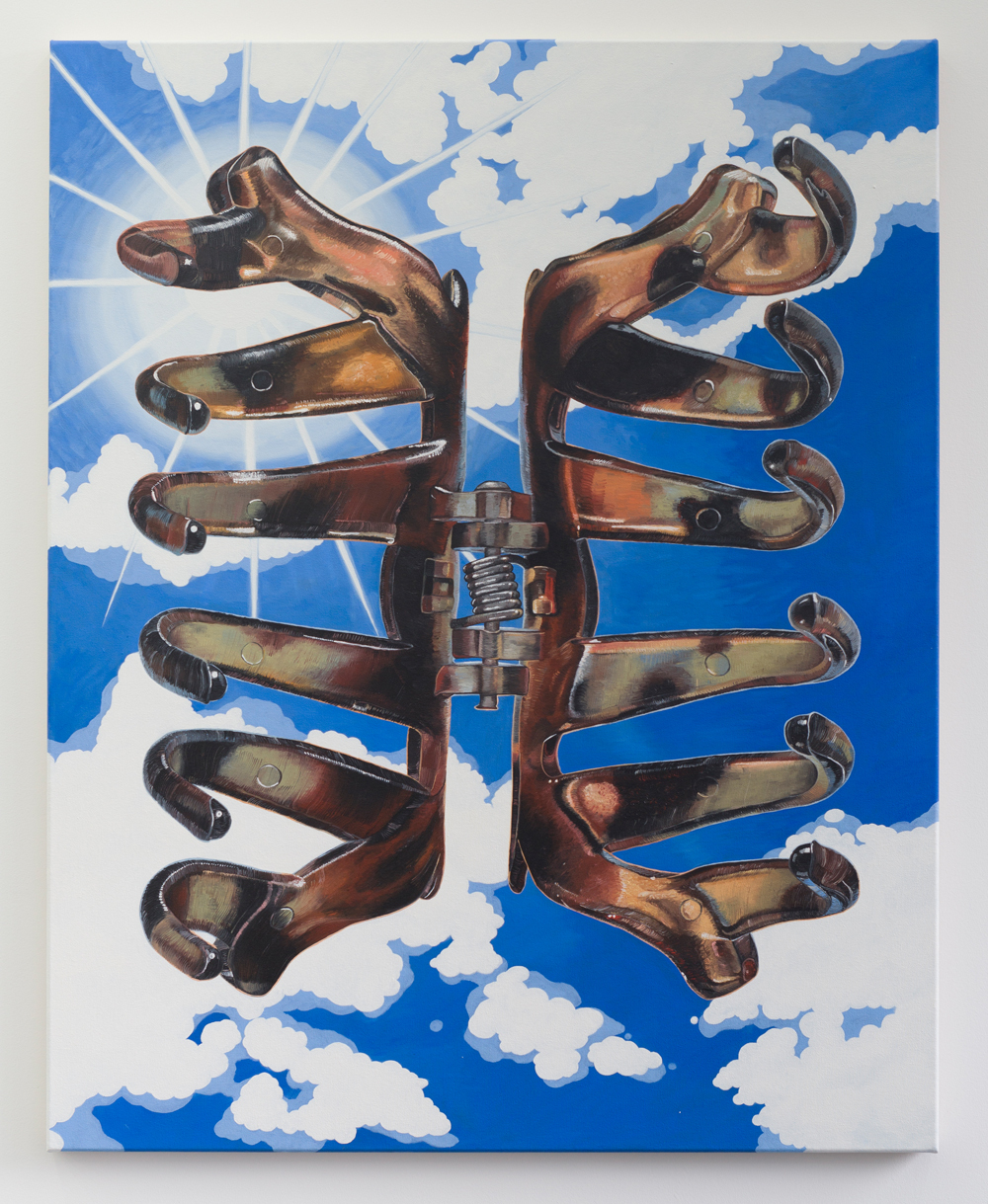

The clip becomes a motif throughout. In Butterfly, spheres of shimmering light transform the functional moulded plastic into a celebrity. The spring, front and centre, holds the whole thing together. Just seeing it coiled, prepared, exposes it as a snapping jaw, desperate to grab hair in its mouth.

The figure in Chapman's paintings is always them, and brings to mind traditional 16th Century Renaissance portraiture, in which states people would choose to document themselves with the things that make them the most them, creating documents that would surpass their lifetimes. There is much of this self-awareness within the work. The paintings seem very aware of what they are, leaning into the flat planes they embody, the use of stroke and technique is purposeful, visible. The medium used historically to capture people at their most poised, Chapman undermines by including unfiltered blemishes of the everyday. Spots and blotches scatter across the skin in the paintings, angry marks demonstrating that our bodies are always in process.

Eyes multiply around the gallery, their gazes scanning, clocking points scored. Looking is made an example of, blue eyes layer on top of each other or face off against the tennis balls. We track these eyes as they move across the paintings that surround them, over the courts and the backs of heads. It is this surveillance that we are invited into, while also realising it is that very action in which we are participating.

In tennis, the word love means nothing. A zero. To play the game is to play for love, athletes will say. In these paintings, Chapman shows us nothing. In these paintings, Chapman shows us love, they show us how the things that surround us and define us build up the tactics and methodologies that we need to chip away at the prescribed monotony of our neoliberal present. They site us in a play of both allowance and refusal, of looking and being complicit in allowing the gaze of others to proliferate. They propose this to us with an earring, a glimpse of fabric, a butterfly clip, and take these small celebrations onto a court where we can play a game for a new future, our hair tied back, warming in the sun.

Lisette May Monroe 2022

Kendall Koppe is delighted to present Love Game. This is Hamish Chapman’s first solo exhibition with the gallery. Chapman was IN RESIDENCE at the gallery in 2021 which culminated in presenting a new body of work at Paris Internationale 2021.

Hamish Chapman (b.1993, London) lives and works in Glasgow. Upcoming solo exhibitions include Meadow Mill, Dundee (2022) and Quench gallery,Margate (2022) Recent projects include Meltdown, Ridley Road Project Space, London; Windsor Terrace, Glasgow (solo, 2021); Paris Internationale (2021); A Queer Anthology of Wilderness, published by Pilot Press and its accompanying exhibition A Horizon is not Straight, Tenderbooks, London (2020); queer tim s school prints, Gallery of Modern Art, Glasgow (2018).

Lisette May Monroe is an Artist and Writer based in Glasgow. Lisette is also the co-director of Rosies Disobedient Press with Adrien Howard. Rosie’s is an artist led publishing project focusing on writing from marginalised perspectives with a focus on queer, working class and feminist writers with accessibility to writing at its core.

Lisette May Monroe