Archive

2022

KubaParis

heavy-ornament

Location

Studio PRÁMDate

23.05 –30.05.2022Curator

Šárka KoudelováPhotography

Anna PleslováText

(...)

You've got cucumbers on your eyes

Too much time spent on nothing

Waiting for a moment to arise

The face in the ceiling

And arms too long

I'm waiting for him to catch me

Waiting for you to embrace me, oh-oh

A young girl standing on a private pool springboard slowly begins to move, as if concentrating a long-accumulated force. She holds her clenched fists against each other like two poles, an anode and cathode, moving her own body and the still-calm surface beneath her. What she's wearing evokes a recent catharsis - perhaps only a second away from the moment she was dressed as a typical teenager - but now her entire appearance points to an unspecified ethnofuturistic ritual of partially destructive transformation, for which she needed a multitude of amulets as well as war paint. Strands of her matted long hair partially cover her face. Maybe she's trying to stave off the end of the world, maybe circumstances drove her to the desire to wreak revenge, and she decided to start the storm in this very pool. The jerky dance moves and hand gestures control the water, which is coming alive and it is bubbling with a dark, long-held energy. The surface was already half-covered with dry leaves, and the face of an elderly man watching the dimming dystopian scene from the safety of the house reflects an indifferent unconcern and perhaps a little fear. Just one drop of her saliva is enough - or is it a tear? - and the still melancholic grey sky gets dark, and the water erupts through geyser after geyser.

The music clip for "When I Grow Up" by Swedish composer, singer and producer Karin Elisabeth Dreijer, directed by Martin de Thurah, has become almost cult-like since it was released in 2009. The melancholy atmosphere and the story of the transformation, visualized by the neo-shamanic figure of a young girl, is easy to see as a new mythology, resonating with contemporary experience. The lyrics of the song, in which we suspect the silent revolt of a child disappointed by unreciprocated affection, facing a cold disinterest, can also be understood, thanks to the clip, as a metaphorical capture of the young energy that brings an end to the old order.

In the opposing couple from the video, that is, in the characters of a young girl, yearning for recognition of the rightfulness of all her emotions and an aging man who clings to the remnants of the old order, fear masked by both indifference and aggression, it is impossible not to see the picture of current socio-political problems.

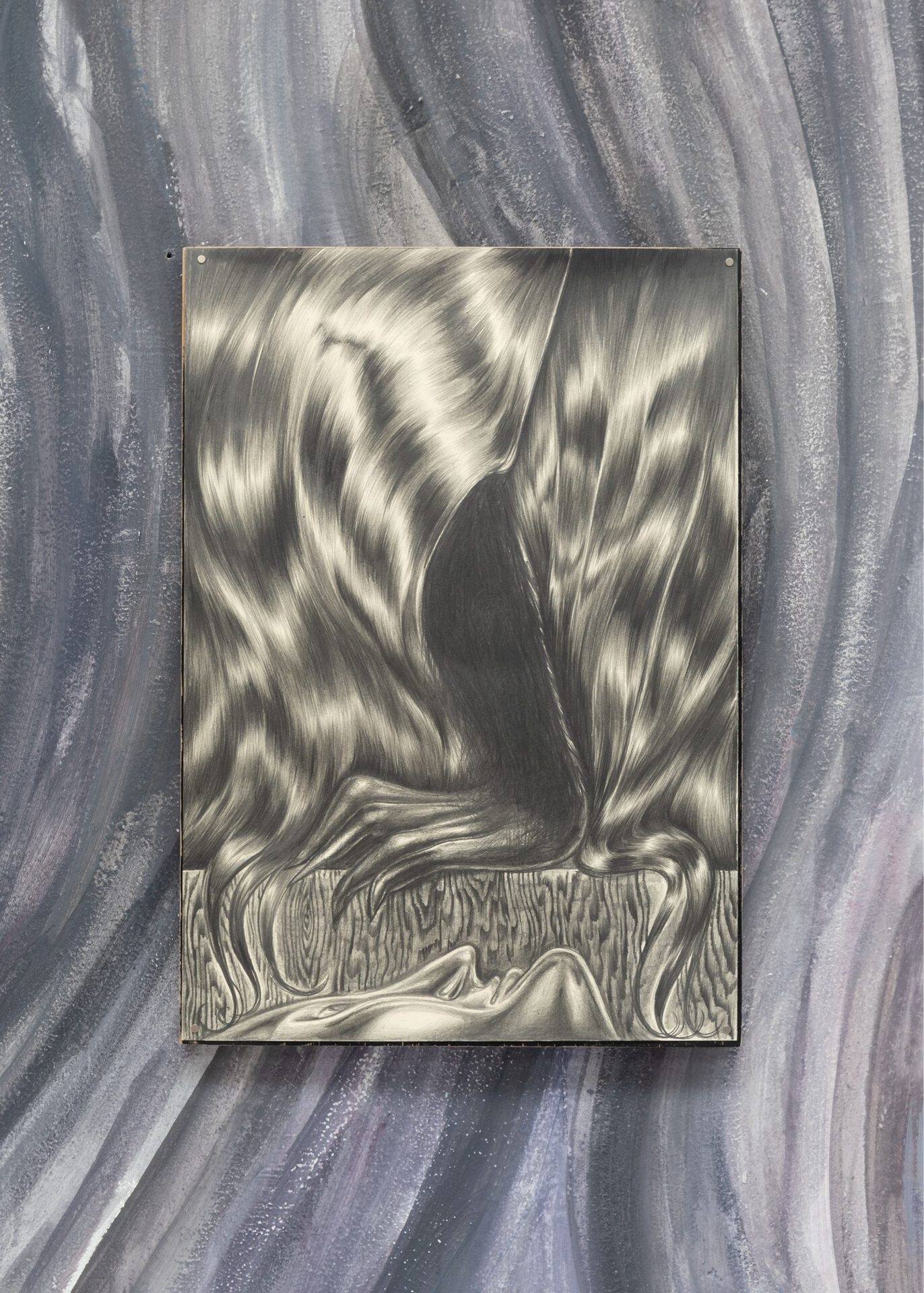

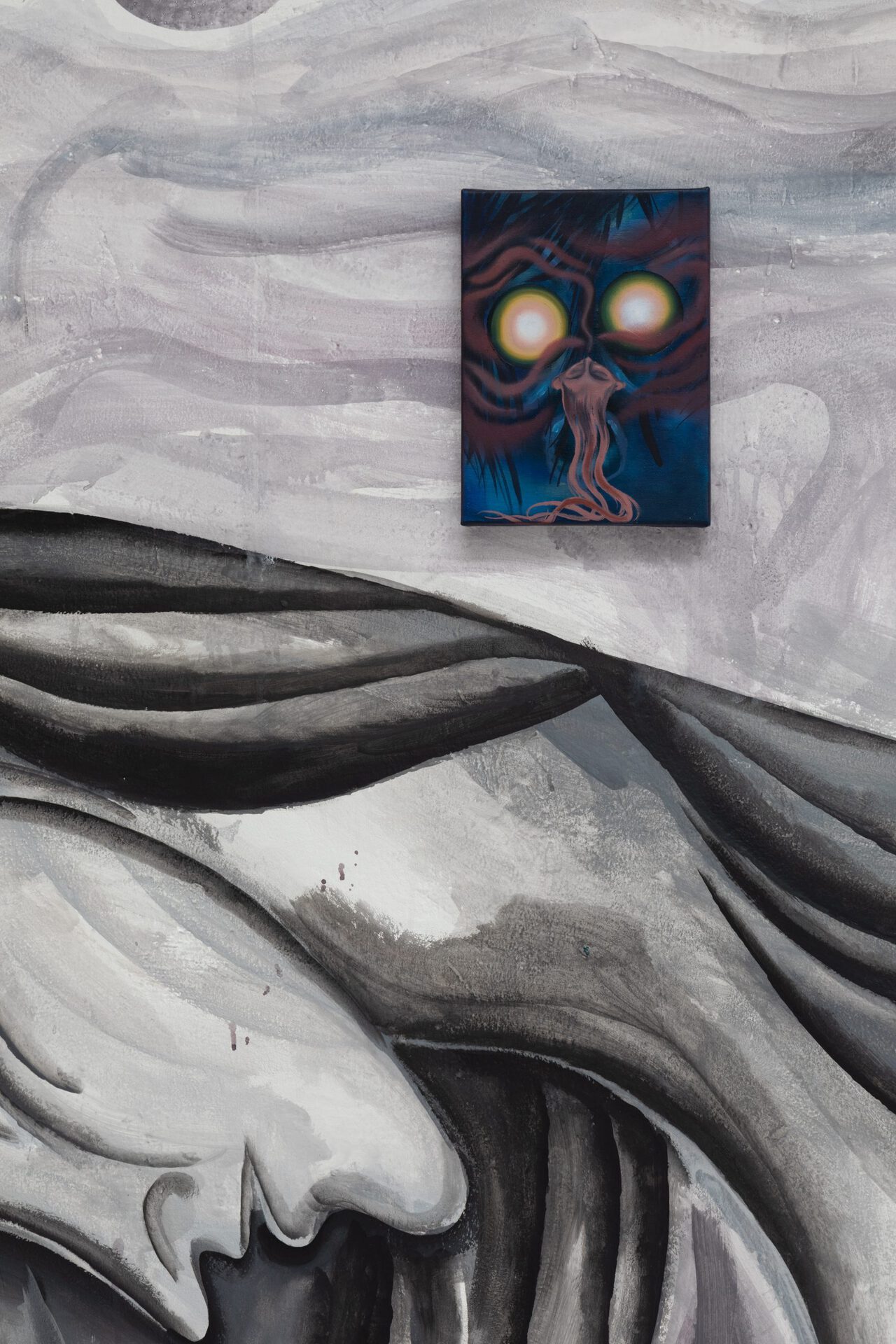

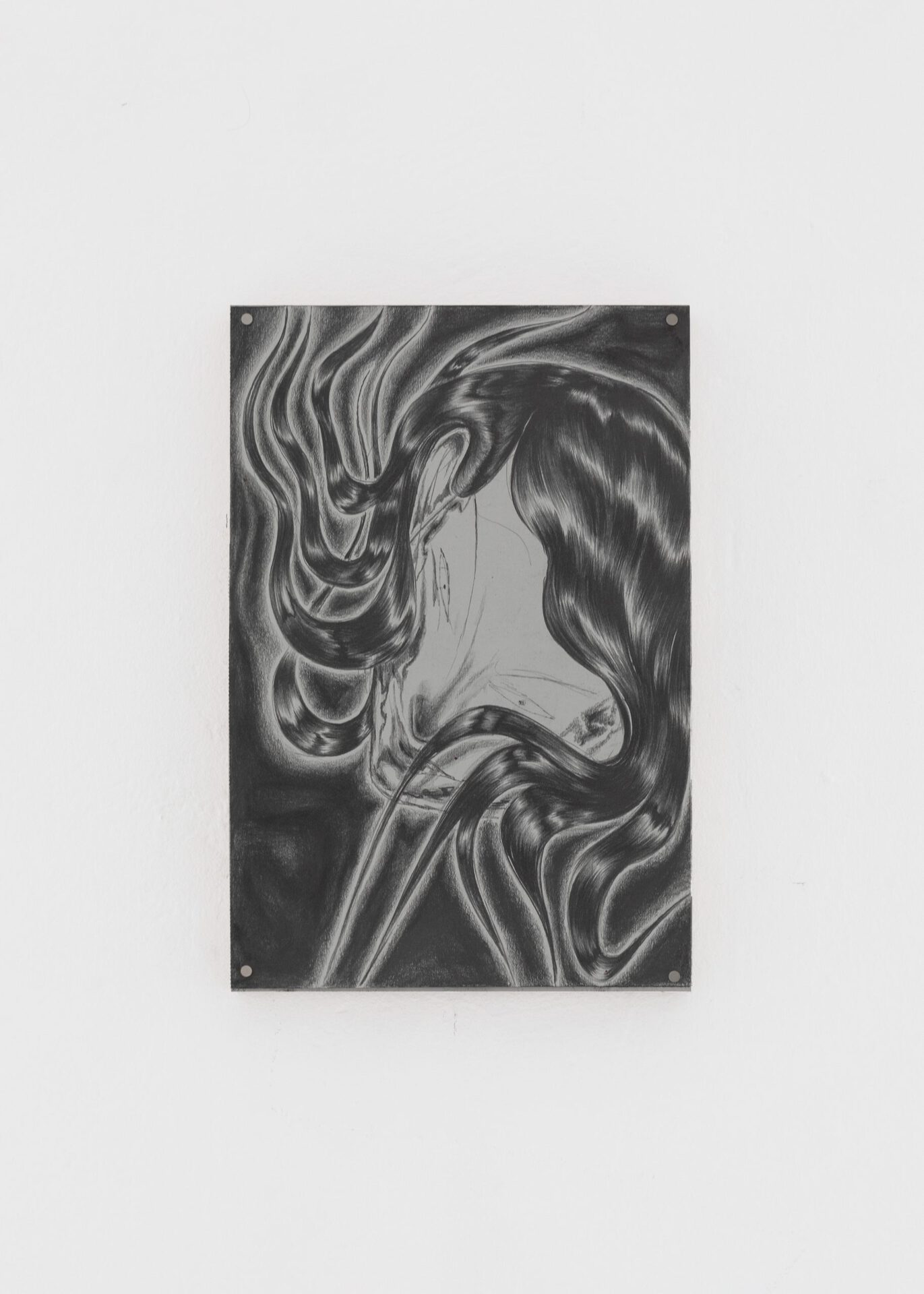

Paweł Olszczyński's pencil drawings are almost intoxicating in their fascination with structures, concentrated in subtle formats. Between contrasting annual rings of plywood, latex-shiny hands and demonicly deformed faces, the seductive texture of flowing hair that flows like a glistening river is repeated, braided into tight braids, or comes to life like Medusa's snakes. Hair is itself a multifaceted symbol that can evoke positive and negative emotions depending on the context. The thick mane symbolizes health and youth, success and power. In contrast, even a single hair on the edge of the plate is enough to make us feel absolutely disgusted. In Paweł's drawings, the ambivalence of hair works as a metaphor for the dark seductiveness of female power with which his hybrid female heroines fight their revenge for equality. Another recurring dichotomous motif is the tear, whose sad but aerodynamic shape can also be used as an offensive weapon in Paweł's drawings. Paintings on canvas, which complement the cycle of drawings, naturally leaves behind the graphic nature of expression. By their colour scheme, limited to greys, blues and purples, they symbiotically subvert the belligerence of drawings with decadent melancholy. The concentrated strength in smaller formats of both colour and black and white works is supported in the exhibition by a wider scale of wall scenes. Their motifs and cover of the space refer to period decorative architectural elements and Paweł's research on works by Czech symbolists, most obviously Portmoneum by Josef Váchal, as well as paintings by Jaroslav Panuška, Jan Preisler and Karl Šlenger.

The way Paweł communicates the main idea of his work, the fight for equality for the oppressed, whose largest and most visible group is women, essentially coincides with the encyclopedic definition of the symbolism movement. Symbolism was, at the end of the 19th century, an emotive response to revolutionary socio-political change as well as to the pre-apocalyptic atmosphere of the end of the century. The main effort of the artists has been to make phenomena available through emotion, intimation and suggestion which we fail to describe rationally and directly and of which we avoid such description. Thus, in the current feelings between the pandemic, the impending war danger, the climate crisis and the fear of the "end of the old world order," the advent of neo-symbolism is not surprising, nor is the renewed shift to mysticism and nature. It is not only in Paweł's native Poland that demons, which we have tried for decades to finally forget, have awakened in the society. Many of us wonder how this could happen, why is history repeating itself again? Weren't we paying enough attention? The history that passes before our eyes is like a comforting pattern on wallpaper, we look into it for so long that we can't see how the originally graceful ornament changes shape and makes our heads spin.

/Šárka Koudelová, 2022/

Šárka Koudelová