Archive

2022

KubaParis

Hex

Location

Galerie DerouillonDate

12.01 –18.02.2022Photography

Gregory CopitetText

Alex told me that in England, according to superstition, people will salute a magpie whenever they see one, the way a soldier salutes a general. Should you not do this, it then becomes a portent of bad luck.

This magpie follows us with its assertive gaze, staring at us with a look so piercing that nothing seems to be able to escape it. An "evil eye" which gives the exhibition its title. With this superstition, we respond to the intensity of this gaze and to the discomfort that it makes us feel by trying to get rid of it, by waving it away with our hands.

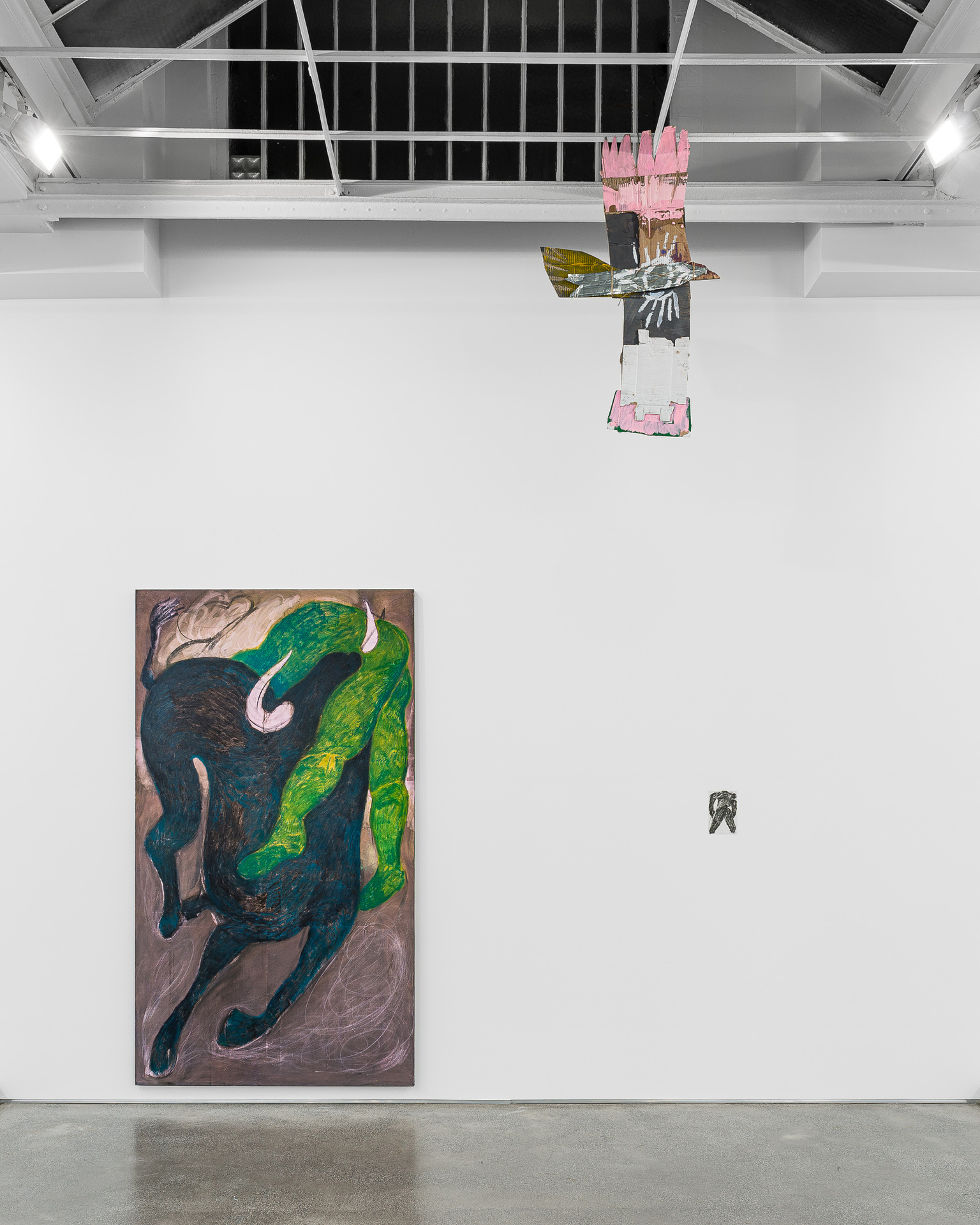

It’s this violence and obsession with the gaze that drives Alex Foxton’s work. The magpie is always affixed with an eye on its plumage, highlighted within the exhibition, and becomes the general symbol of the pressure inflicted by the codes of masculinity. These cross-shaped birds are the harbingers of obsessive images, archetypes imposing an unbearable gender identity which is constantly renewed by the historical and popular characters that populate our collective imagination. Foxton thus summons various figures, which are sometimes already familiar throughout his paintings: sumos, bullfighters, Greek statues, all sorts of models who alienate us. The eye has become a recurring element in his vocabulary, appearing from canvas to canvas alongside other the terms within his lexicon as a painter: glitter, intense colours, charcoal, scratched canvas.

“Hex” starts with shattered glass from broken sunglasses, which opens the story of this very personal exhibition. Foxton deconstructs his typical uniform on the first canvases, reminding him of his father’s uniform and of the man who was his first male model. A pair of black glasses, leather derbies, a blazer, a straight coat, a white shirt and tie. The black and white of the clothes can only let us see the folds and signs of its usage carved in charcoal and oil, a uniform that only lets us guess the contours of the body that slips into it. Much like a portrait of the artist, they bear witness of an obsessive absence of its body, which is not portrayed, but only existing through gestures. On the walls, the drawings rub shoulders with the paintings, without any sort of hierarchy. They are not mere studies; they have a fundamental importance for Foxton, revealing the strength behind his initial gestures. The coat and shirt slip around the blazer-like layers of more-or-less warm clothing, the small charcoal on paper challenging the large gored bullfighter of Bullfight (Green) on the center wall, the strong legs of the sumo wrestler a response to the dismembered busts. The intimacy of the medium creates a closeness with us and draws us into a face-to-face encounter with the work.

Yet, the figures in Alex Foxton’s work (almost) never look back at us. As if these people had lost their power to exist, incapable of handling our gaze and the desires it projects. Only the Sumo glances directly back at us. Only the man who has escaped the Western norms of a desirable body would be automatically freed from this yoke. Although they always borrow from these archetypes of a fantasized version of masculinity, the bodies Foxton has painted are all fragmented, damaged. The torsos have been amputa- ted, the heads cut off from their necks, the Greek statues revealing the metal frame supporting them, the perfect bodies of the bullfighters overturned and gored by the beast in a macabre dance. The portraits, loosely associated with the bodies of bullfighters or Greek torsos, bring together the emblematic figures of twentieth-century culture and its stories of homosexuality, whose lives and works were shaped by a form of emancipatory violence. Foxton summons Michel Foucault, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Yukio Mishima, and Justin Fashanu (the first English footballer to come out of the closet) in response to these broken idols.

Contrasting with the constrained desire emanating from the canvases, a profound freedom emerges from the artist's gestures. Alex Foxton does not treat painting like an image, but grabs it and shapes it like an object. He exposes how the canvas has been stretched, its frame, its staples, and tests its limits. The frame of Bullfight (Yellow) becomes the spine of the upside down bullfighter, structuring a rib cage with its bars; Butcher Knife is modeled with thick layers of paint and charcoal, which are spread out and scraped on, and whose volume is enhanced by a mortar made of crushed coffee beans. Foxton goes even further with Magpie (Moon) by sanding down the contours of the eyes, getting rid the edges and punching holes in the center of the canvas, revealing the wood of the frame. The scratches reveal lighter layers underneath the depth and velvety texture of the char- coal, as if it were a memory of the painting. The bright colours of the birds and the bullfighters' clothes burst forth from the general black and white atmosphere that accentuate its hanging. These are made of recycled cardboard, recalling playful and childish collages whose simplicity could counteract any menacing gaze.

Foxton's story of the eye shares elements with Bataille's, summoning the tangential eroticism of death, like a bullfighter's movement which preserves the extreme beauty of the gesture, and the meeting of those two bodies towards the ultimate threat. Alex Foxton deliberately breaks free from the artificial canons of masculinity and focuses on the fragility of these characters, returning to the vulnerable depiction of a body struggling with its emotions. The butcher in Hex is the only figure whose entire body is actually imposing, making the violence his own, and seeming to turn it around with a precise gesture that thrusts this thundering knife into the canvas right in front of our eyes. This story of the eye is, above all, a story about a painting going beyond its status as an image in order to become a full-on embodiment.

Don't forget to salute the magpie on your way out.

Marion Coindeau

Marion Coindeau