Archive

2022

KubaParis

Materials for Virtue / Incandescent Flare

Location

BRITTA RETTBERGDate

04.05 –10.06.2022Curator

Àngels MiraldaPhotography

Dirk TackeSubheadline

Yen Chun Lin, Teresa Margolles, Laura Ní Fhlaibhín, Jennifer TeeText

It was March when flowers began to blossom. In the face of everything, the flowers were still blossoming.

It was one year, and then it was two. A relentless cycle of loss and grief, mourning and getting up, standing still, and making do. The long conversation about the distance that exists between us and the mediated image flared back up. Numbers, hospital beds, medical uniforms, protests, police, displacement, war, more displacement. These bare tips of trees always return to flower: their beauty is so reckless, so unforgiving, and so necessary. We find relief in materials that contain longevity that will far outlive us. Like heirlooms passed on over the course of generations, or the archives that contain the names of ancestors, or the fossils preserved in rocks for millennia.

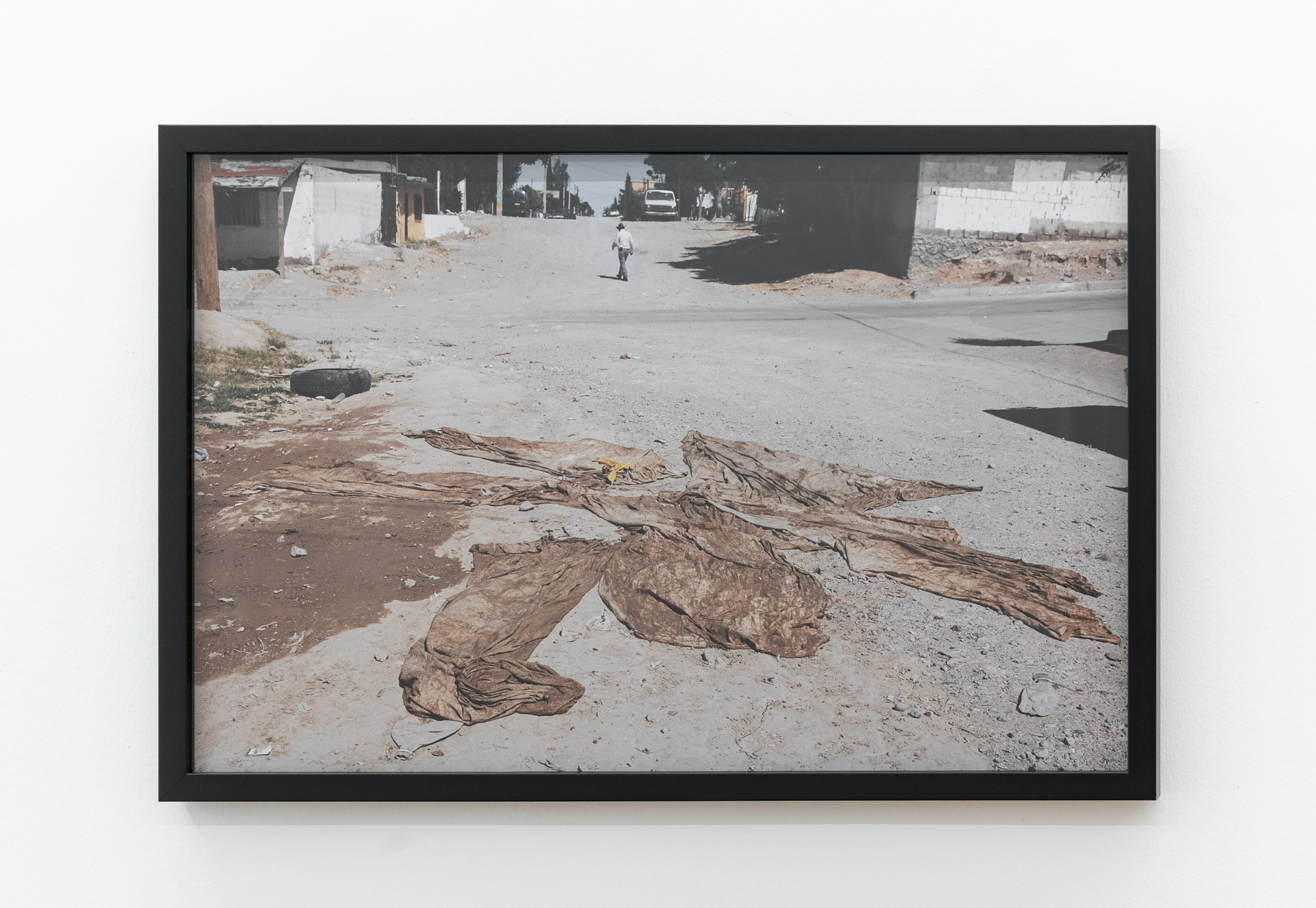

Teresa Margolles is a reference on the distance between materiality and photography. Political contexts related with violence against women, migration, and human trafficking are brought directly into the gallery space to put us face-to-face with past and present atrocities. In Tela en el Desierto (2018) Margolles confronts the landscape dotted with memories of women found in the Juárez region of Mexico where high indexes of femicide continue to plague the population. The fabric is laid out within the landscape where their bodies lay, and is presented next to the photograph, breaking the desensitising barrage of the contemporary news cycle. The horizon on a blue sky is met with the dry cracked topaz earth of unpaved streets where liquid rapidly evaporates into air.

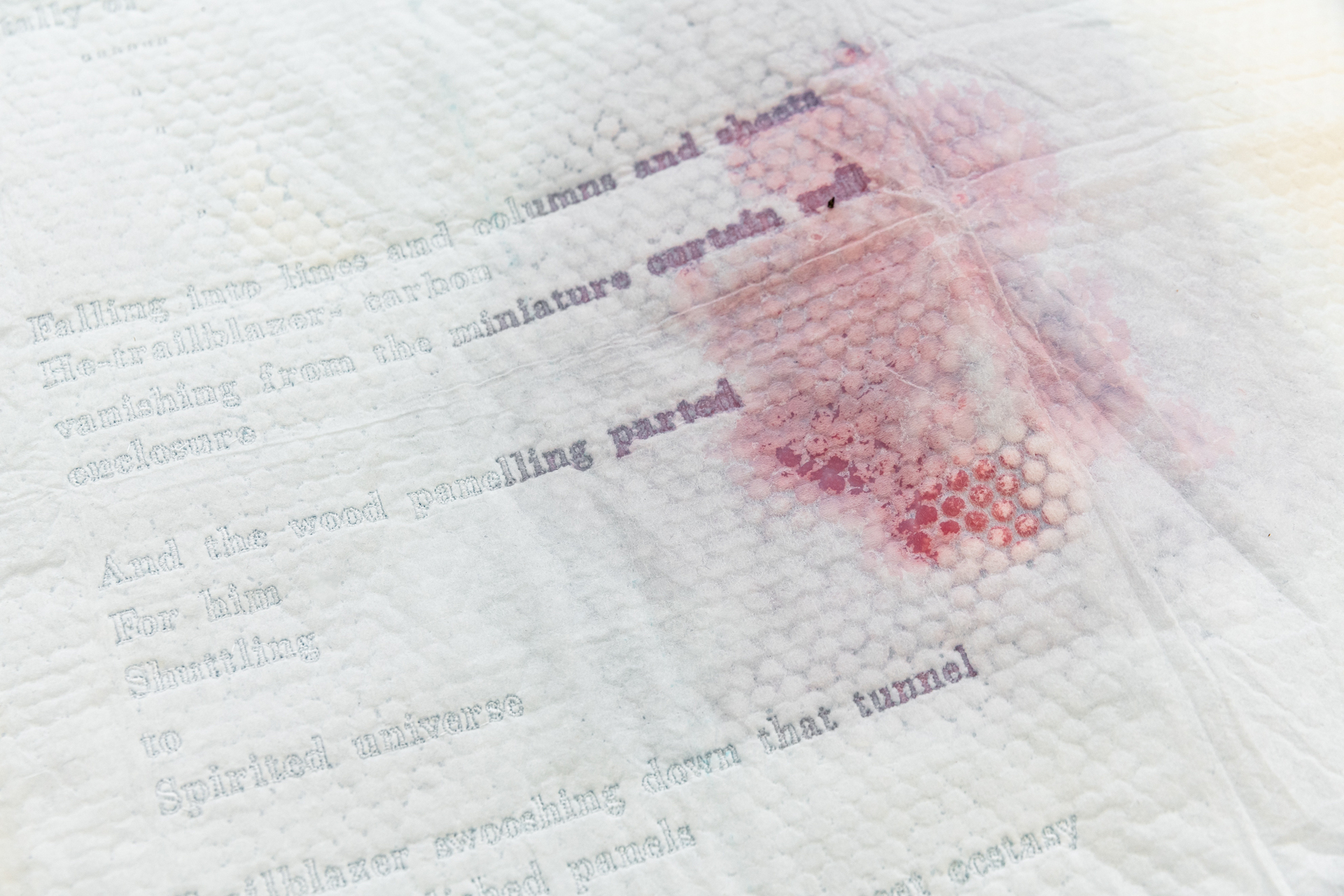

In the rolling hills of South-Eastern Ireland, Laura Ní Fhlaibhín’s works in oil and metal reference personal histories, amulets for an ecstatic afterlife, folklore, and the mortal reality of petro-culture. Cast bronze amulets from earlier clay works, marl spirit creatures, are welded onto lengths of stainless steel chain, conjuring an interconnected system of rupture and repair through the gallery rooms. An often-romanticised rural life leaks into the hyper-masculine motorbike and top velocities on winding country roads. Forest Fungus, gifted to Laura from a friend in Wicklow, is fossilised in bronze and guards the motorbike-oil offering, holding the dead dear. Metal chains and medical equipment pierce through soft materials drenched in oil and carbon. Delicate swirling traces of slugs and spirit creatures on bed incontinence sheets dance like grease on water.

Swimming in a sapphire sea off the coast of Taiwan, Yen Chun Lin had a dream-like vision of a body becoming a whale, and then dissolving into water. In a series of new works, personal experience and heritage merge into an installation that references cosmic listening and reincarnation. One of the beliefs of animalism from the islands around Taiwan is that the soul contains fragments of all beings, including animals, plants, and stones. When someone passes away, these pieces split apart and return to their origins, but we also contain a human element - this one goes to an unnamed reef not far from Orchid Island where they are collected as memory. There, a friend of hers gave her a bone, a piece of a whale’s spine that, being part of the island, contains thousands of unknown memories.

Yen Chun Lin points towards liminal areas, between inside and outside, life and death, between visible and invisible, between audible and hallucination, between material and immaterial realities. Listening to quiet voices is a practice of caring for the world that we inhabit with all creatures. Seven pewter casts arc across the room in a cosmic arc – the last contains a pool of water that catches the sun’s rays at around 3:45pm on bright days. This performance is a brief activation that aligns the sculptures with the sun. A thin red thread ties the sculptures together. Although it is nearly invisible, it traverses this world to a spirit world and to past lives.

Jennifer Tee’s tulip petal collages Tampan Tulip (2014-present) reference traditional Indonesian weavings while reflecting on migration, loss of homelands, and the passage of life. The original designs were made for funerary purposes and for luck to seafarers - sharing the notion of physical and spiritual voyages. These traditional weavings were practised for centuries by artisans who passed on the trade from generation to generation. In them, life is described through understandings of the world from the indigenous populations of the Lampung region in south Sumatra as womb and reflective surface. A world above and a world below generally shadow each other like the surface of the river Styx – a watery separation between here and other worlds.

Tee’s own heritage sparked her initial interest in these objects and has researched them since. Her Dutch grandfather was a tulip trader, and her father migrated from Indonesia to the Netherlands after the second world war. The use of these ceremonial tapestries ceased with the famous eruption of Krakatoa which was simultaneous with the cultural and social upheaval of Dutch colonialism and the extractionism of the VOC. Tulips are a symbol of the Netherlands since the well-known 17th century ‘tulip mania,’ and this still very present cultural artefact melds with one that has been lost. Although much of the original meaning of these patterns has been lost, Tee gives them new life through contemporary retellings that attempt not to artificially reproduce, but to reimagine them from the perspective of a multicultural Dutch society.

The volcano split the island in two, it set the forest on fire. But amid the settled volcanic ash, the first sprigs of succulents grasped towards the sun. Their lizard-like stubby limbs rose, and then those small yellow flowers surrounded by shards of obsidian peeked their heavy heads towards clear blue skies.

The exhibition is supported by Culture Ireland, Taiwan in Deutschland, Fire Station Artists’ Studios and Ramon Llull.

Àngels Miralda