Archive

2022

KubaParis

äußerst ungünstig

Location

Schwabinggrad, MunichDate

16.03 –13.05.2022Photography

Dirk TackeText

The pursuit of ‘happiness’ has come to both determine and contaminate our lives, often depriving us of our agency in the process unnoticed. The exhibition äußerst ungünstig by Lea Vajda precisely explores this tension (re)produced through the standardisation of our hopes and dreams and the marketization of individualized techniques to support their fulfillment.

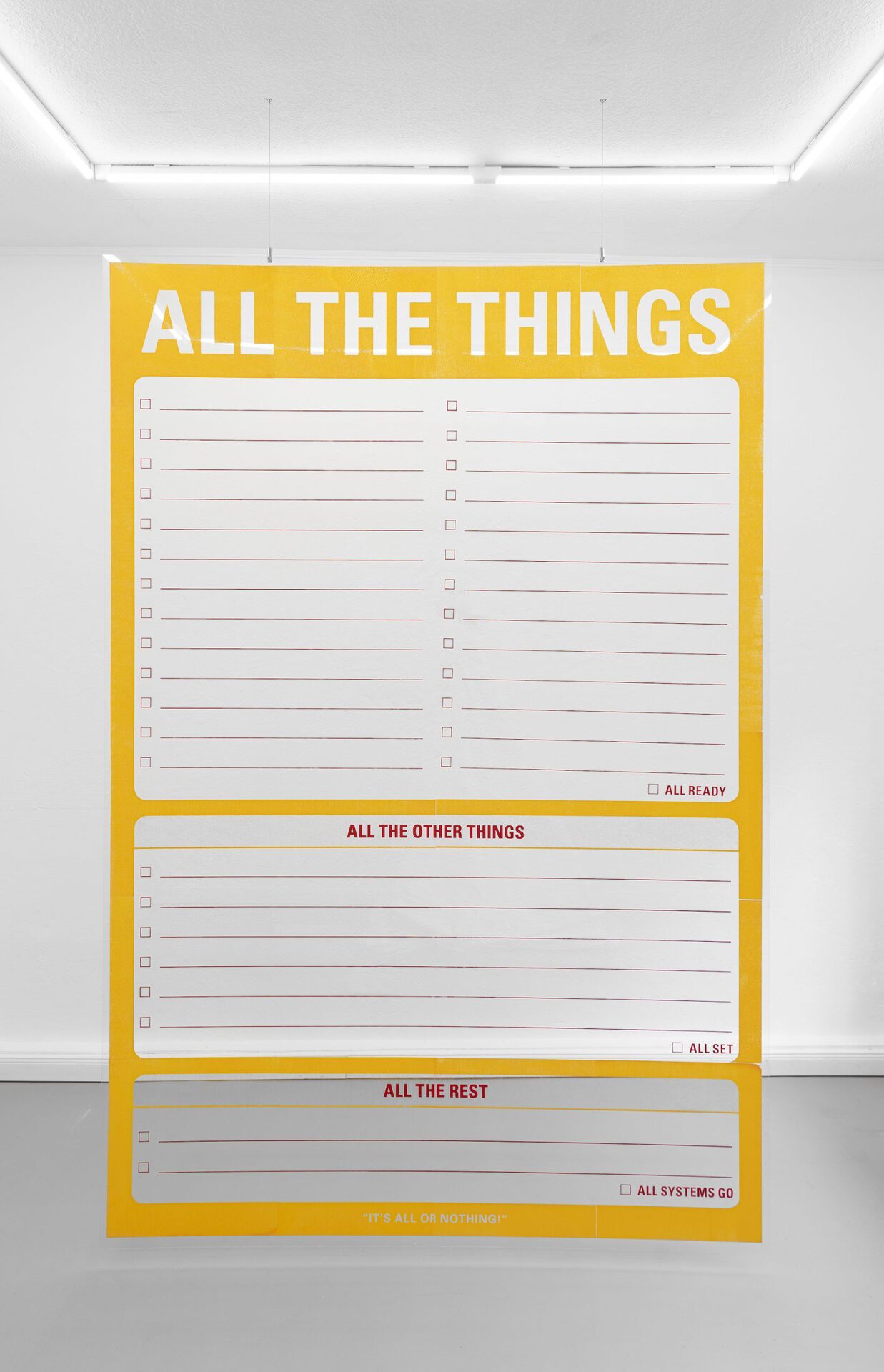

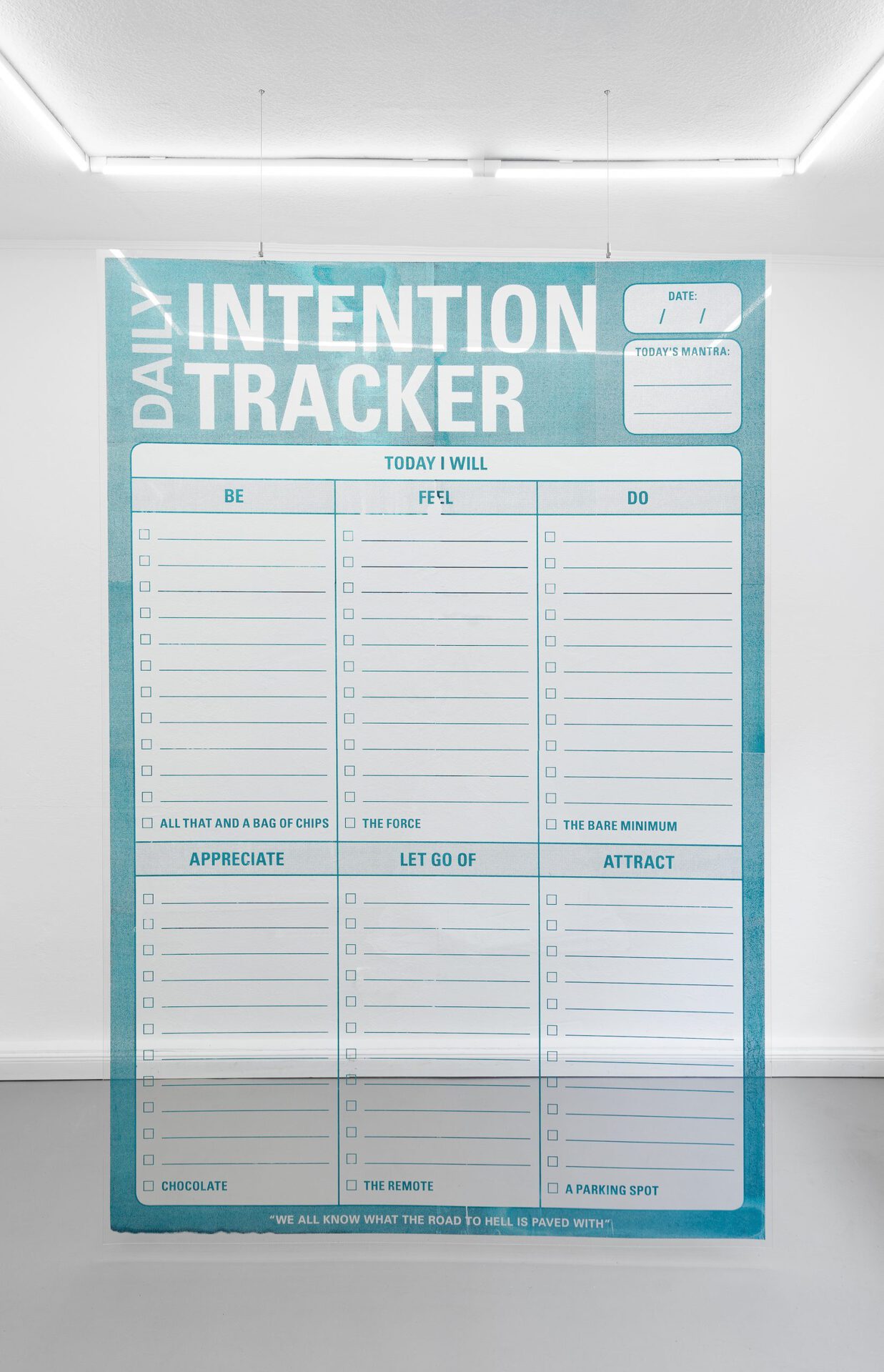

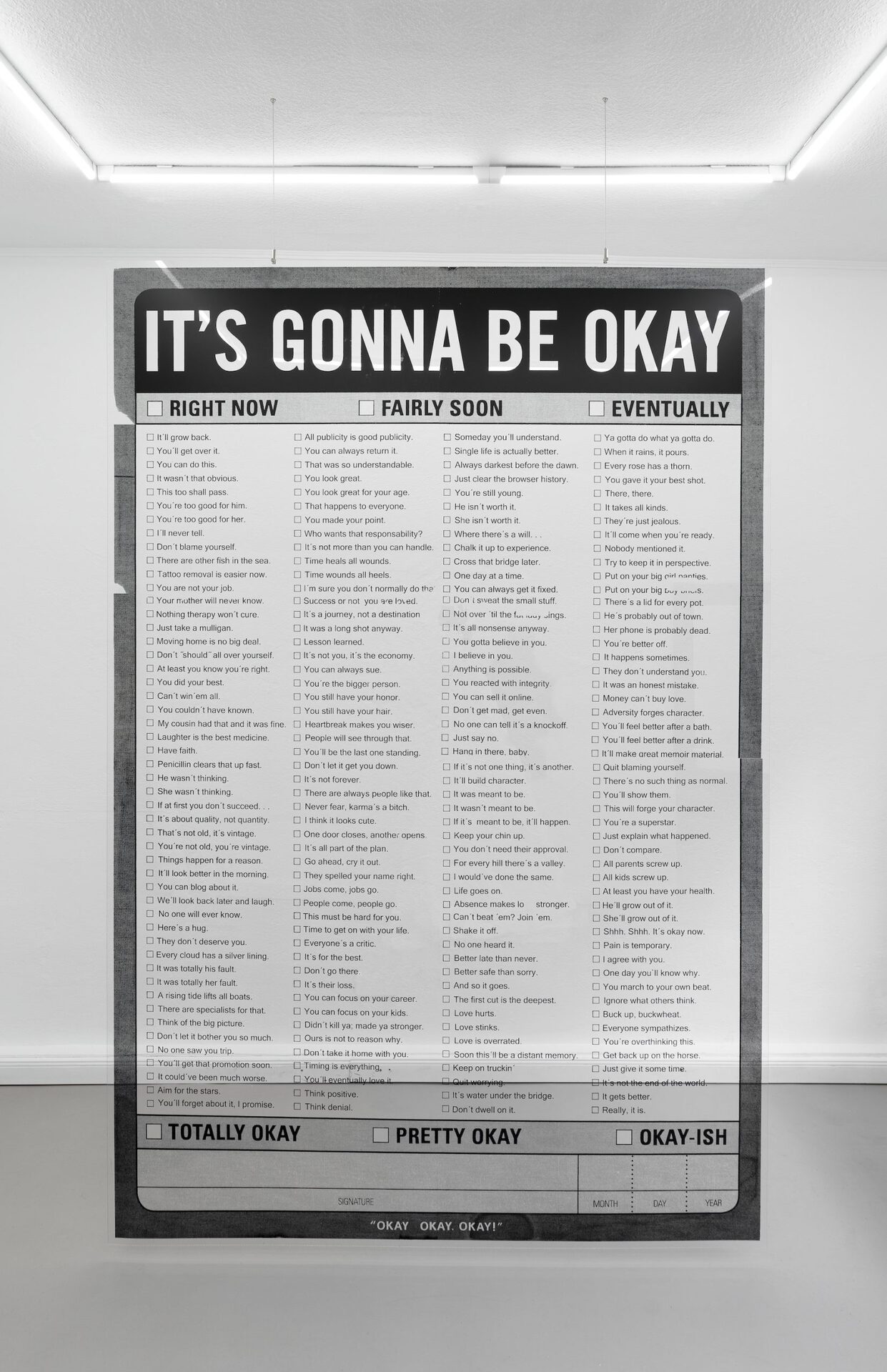

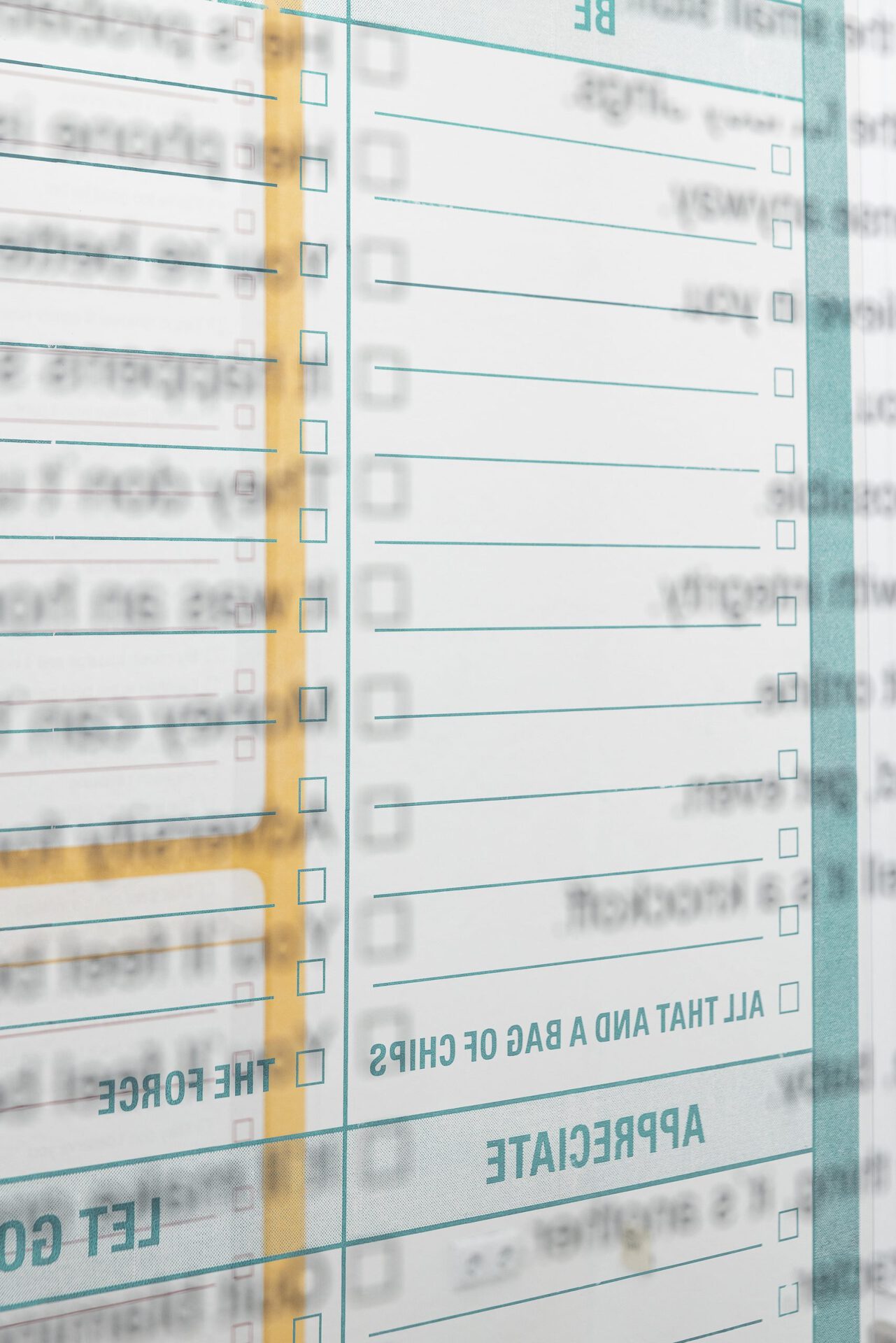

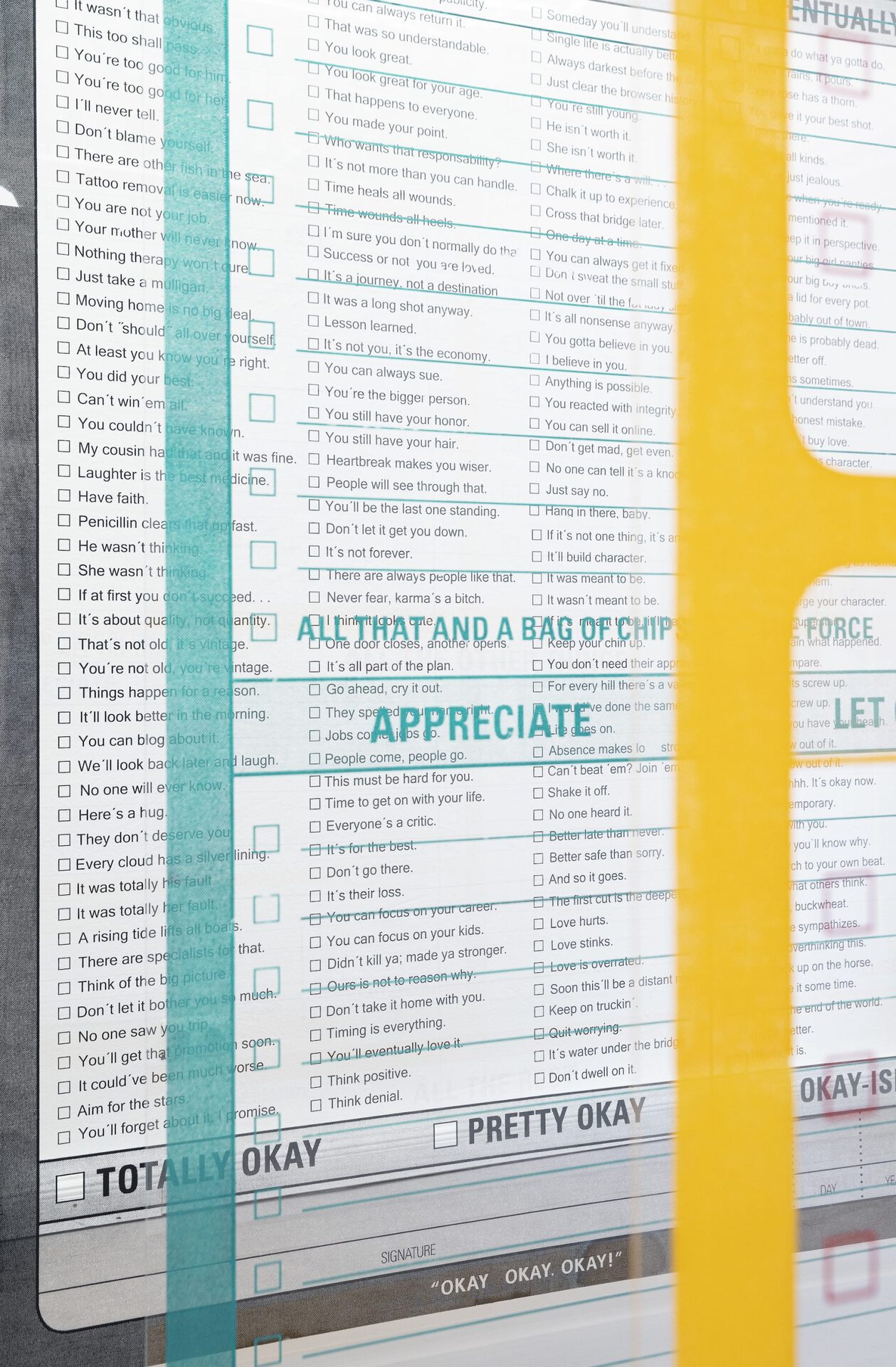

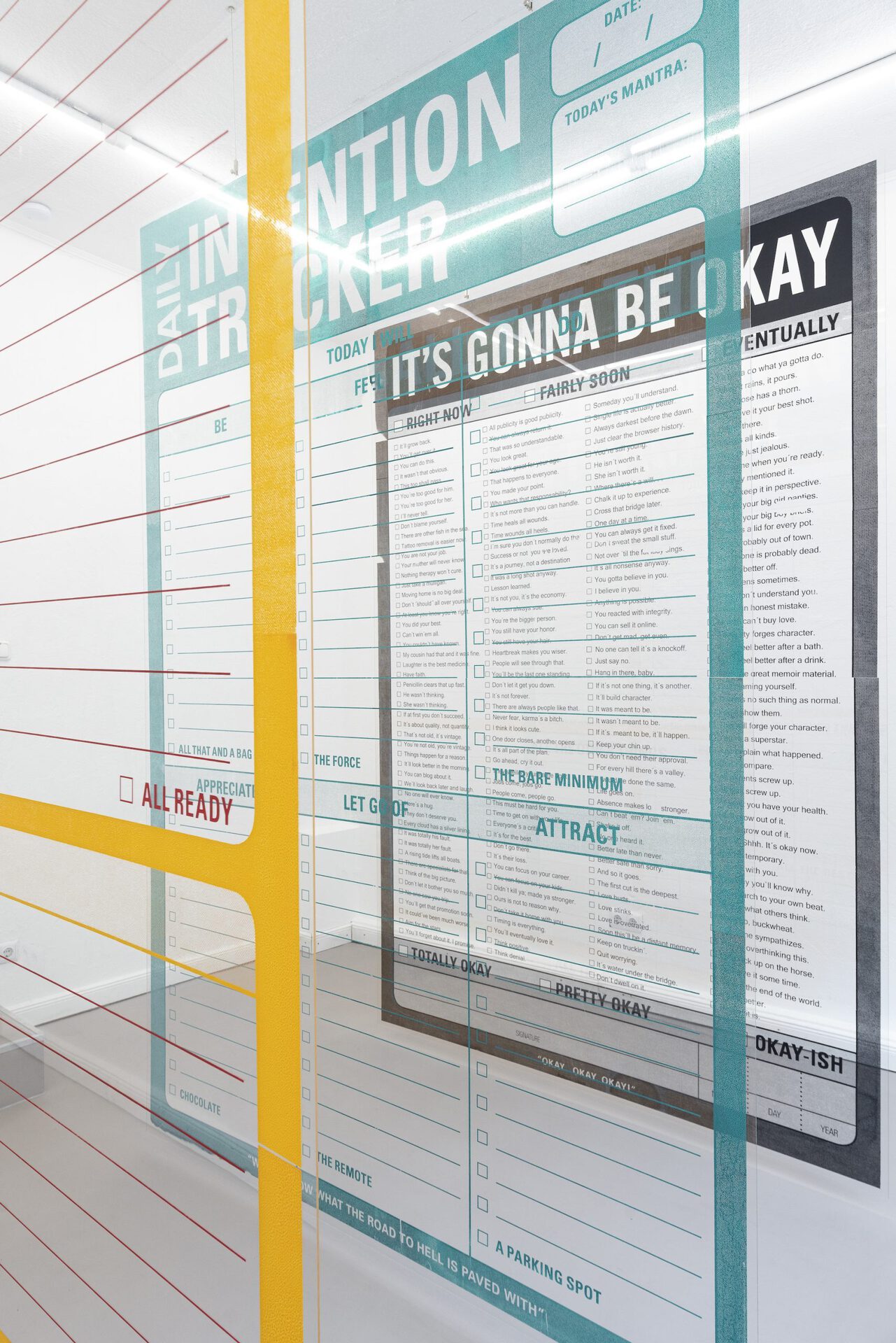

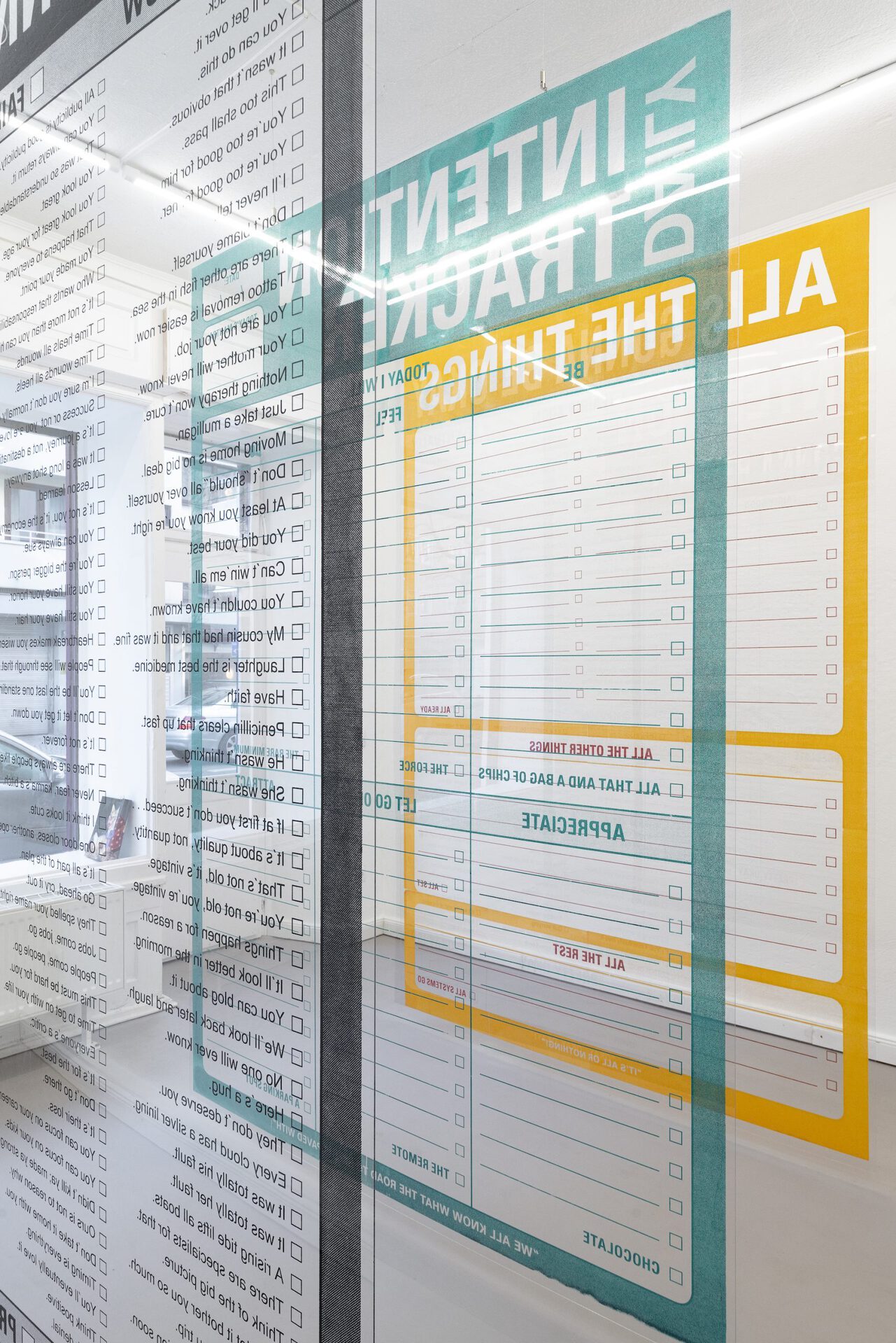

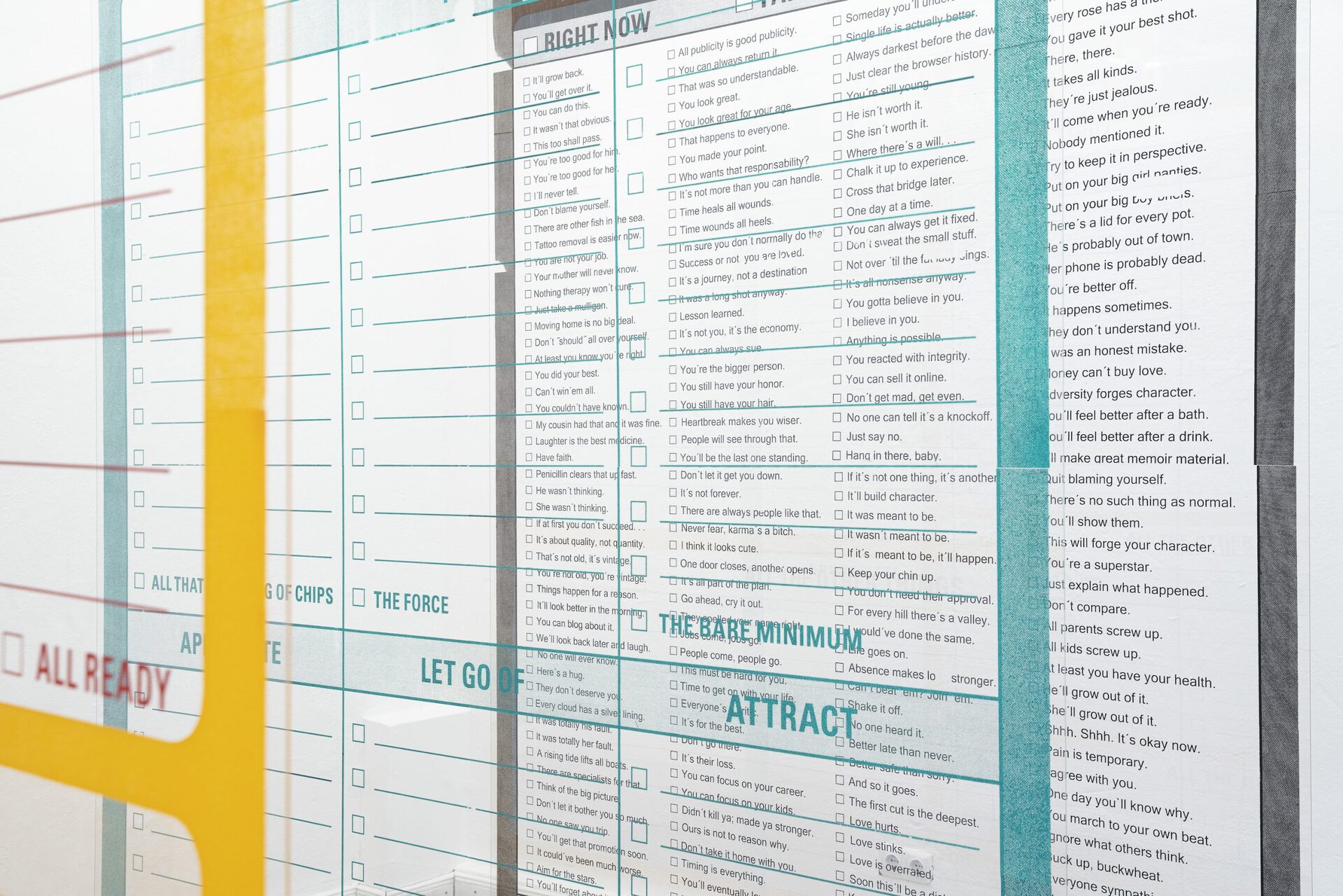

The presented works, three in number and part of a body of work begun in 2020, are enlarged reproductions of found paper tear-off pads transferred onto polycarbonate. Their content is a very narrow sampling of our needs and desires that neatly conform with normative social concepts. The depicted questions and phrases—the lines to fill and boxes to check—evoke interrelated contemporary and market-enforced notions of ‘self-control’ and ‘self- care,’ with their ideological undertones being abundantly clear: from binary gender stereotypes (“Put on your big girl panties.”) and supposed mentally healthy lifestyles (“Don’t ‘should’ all over yourself.”) to an imposed set of emotions (“You’re overthinking this.”) and insidious promises of happiness by overcoming entrepreneurial or personal challenges (“One door closes, another opens.”).

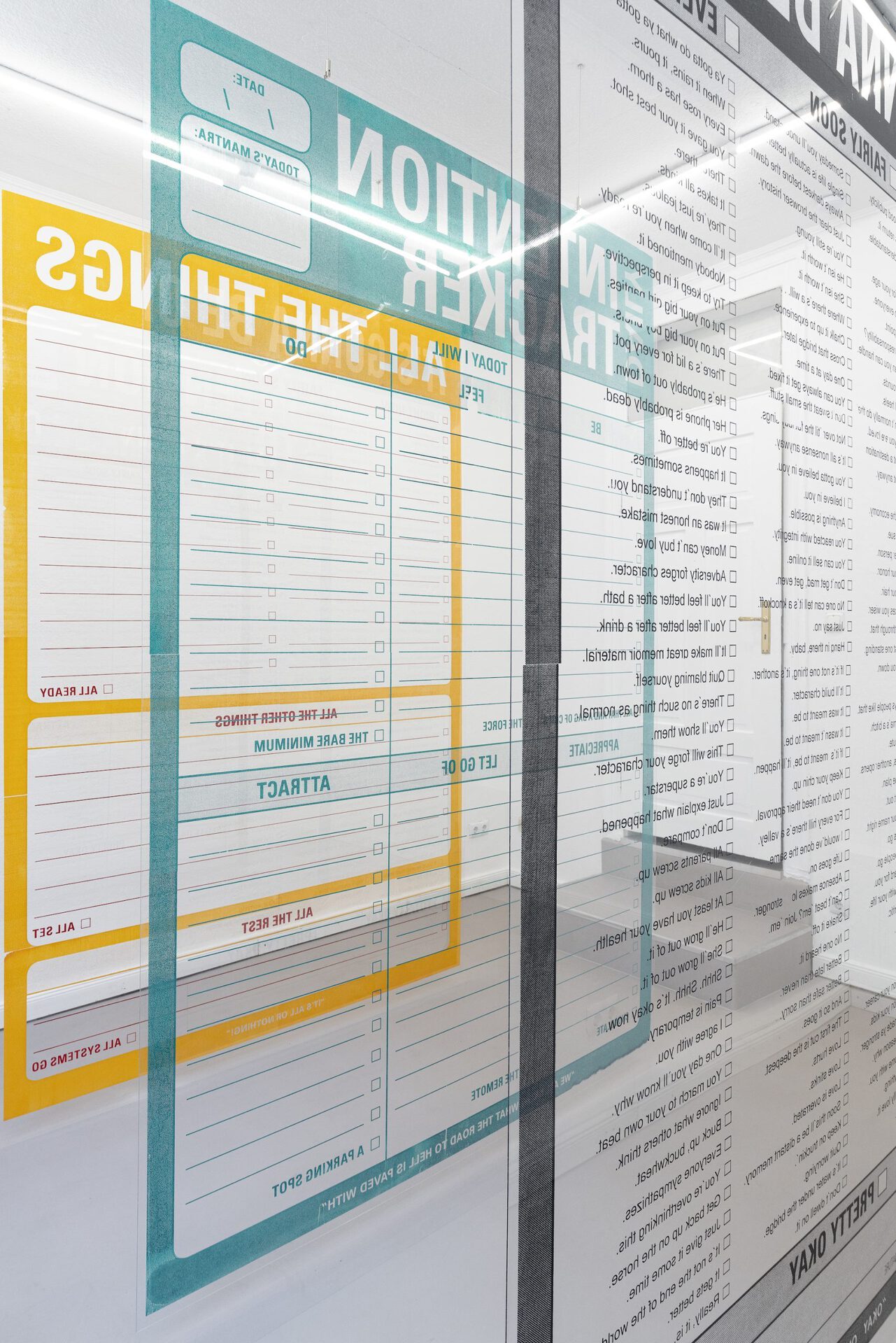

Other than perhaps expected at first glance, the works themselves are not produced industrially but handmade, thus containing several irregularities. These are markers of the difficulties encountered by a single body and its ability to move while producing on such a scale. In this way, and contrary to the promises they portray, the works seem to propose a different attitude towards ideals of (self-)perfection. The transparent prints are installed in a way that they superimpose one another, their respective content materializing only tentatively, occasionally complementing or crossing out each other. Another look at the oversized forms also reveals a comical quality inherent in the works.

Two complementary theoretical approaches come to mind: for one, Sara Ahmed’s widely discussed concept of the ‘promise of happiness,’ in which she ties happiness to structures of the social and exposes desire as a method of regulation based on its prioritization of certain lifestyles and narratives over others. The other being Lauren Berlant’s notion of ‘cruel optimism’ which refers to the structural and psychological dynamics that keep people in proximity to objects and fantasies that in fact seem to diminish them. Or, to put it another way, despite undeniable evidence of its unattainability, we remain stubborn in our pursuit of the ambitious and highly ambiguous ideal of ‘the good life.’

The view of the daily world is a gloomy one: living in a time when crisis itself has become the ordinary, the necessity of care—for ourselves and others—has arguably become more pressing. However, contrary to the history of the term ‘self-care’ and its initial use in the context of collectively organized resistance movements, ‘self’ in relation to ‘care’ today only seems to imply the isolated exercise of shouldering the sole responsibility for one’s own wellbeing. Consequently, it becomes apparent that the term possesses a slippery nature made up of a medley of good intentions, the elimination of ‘bad habits,’ and self-optimization. The works on display explore exactly this double bind of the original commodities, whereby they might act as both anxiety-inducing objects and as helpful tools employed in an effort to grasp something of such enormity, namely the complex relations constituting our lives that effectively can only remain intangible—which of course is the actual beauty of it.

— Gloria Hasnay

Gloria Hasnay