Archive

2022

KubaParis

S(k)ins

Location

Toxi OffspaceDate

18.03 –26.04.2022Curator

Oz OderbolzPhotography

Flavio KarrerSubheadline

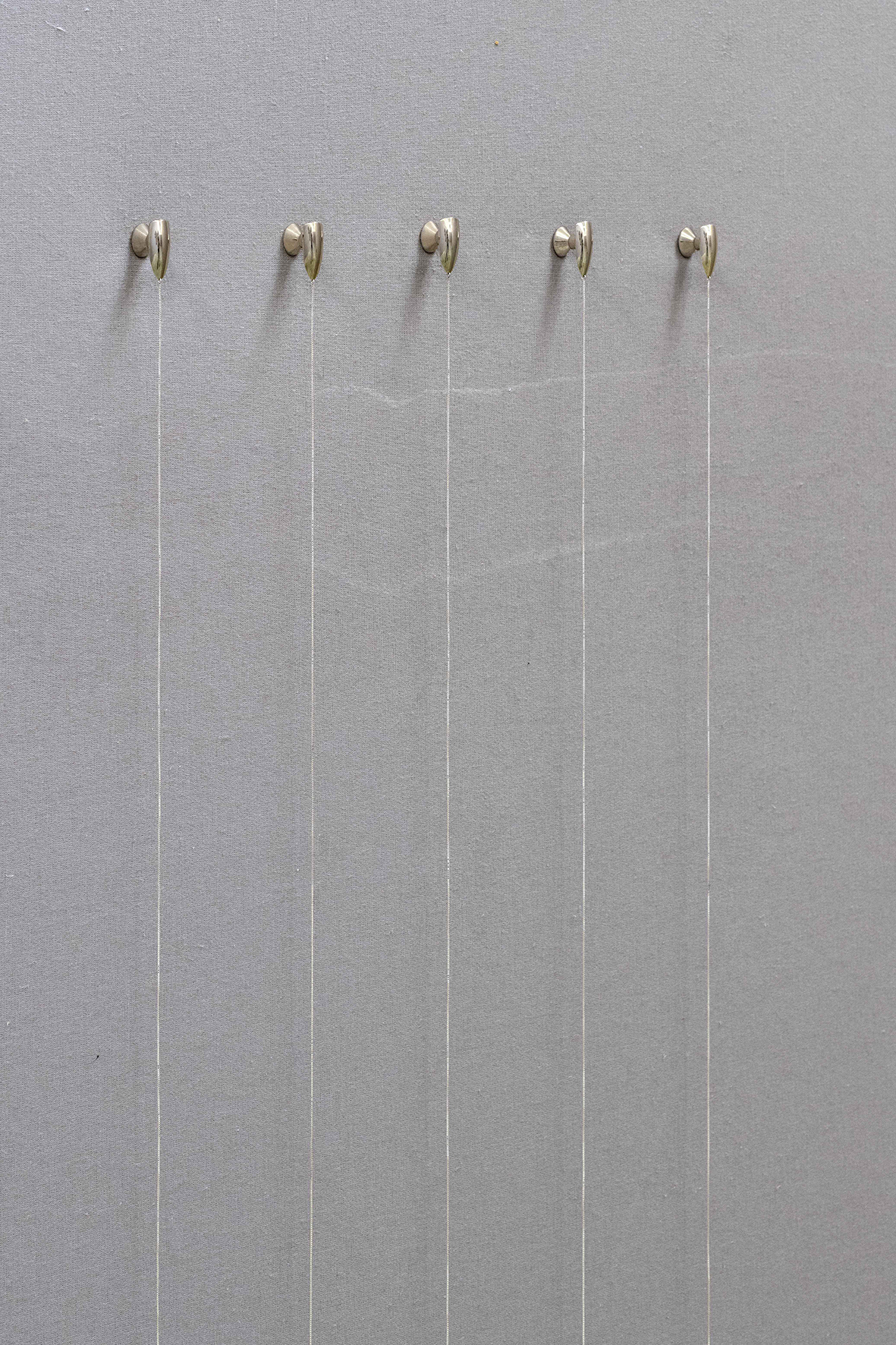

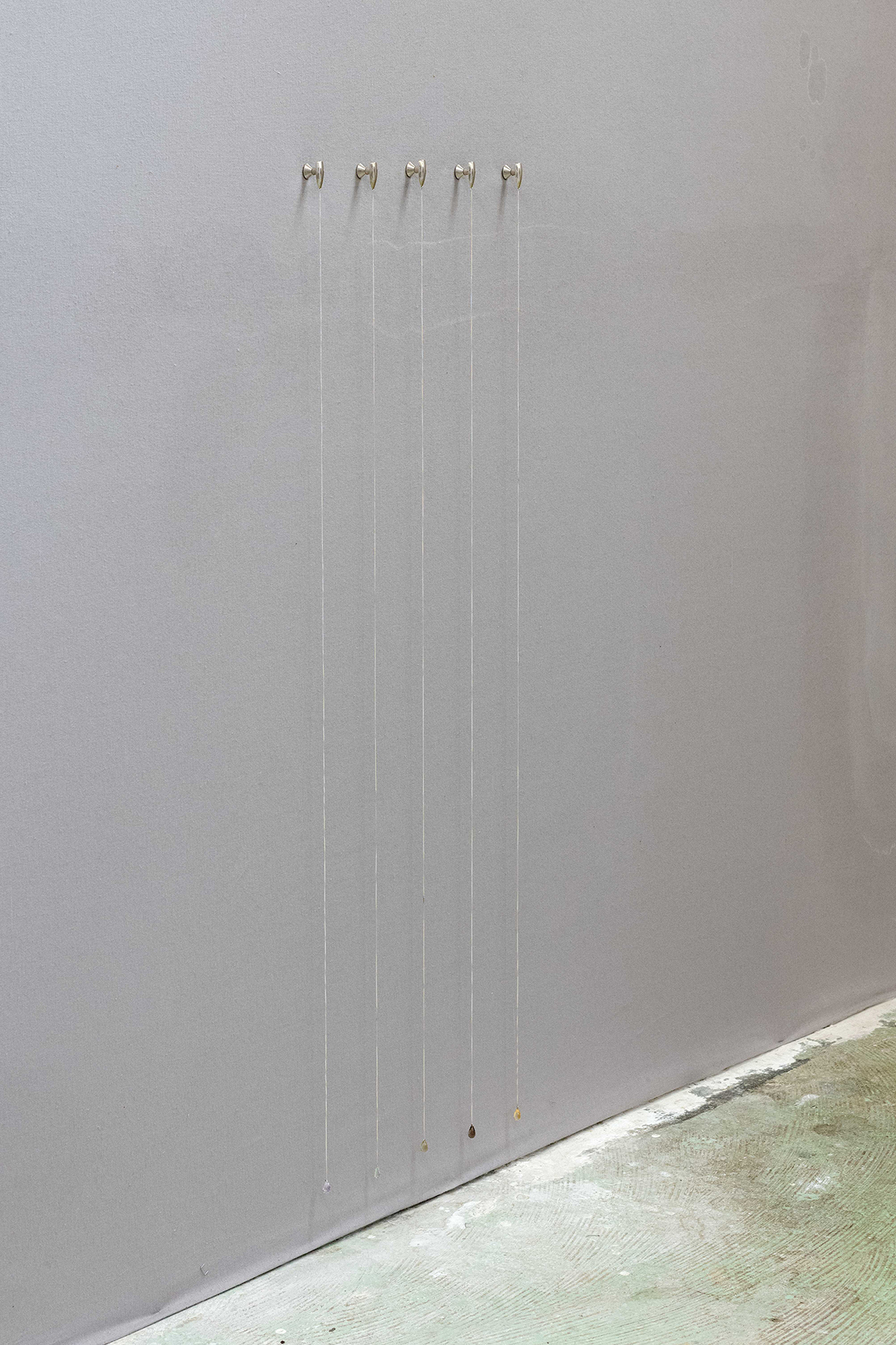

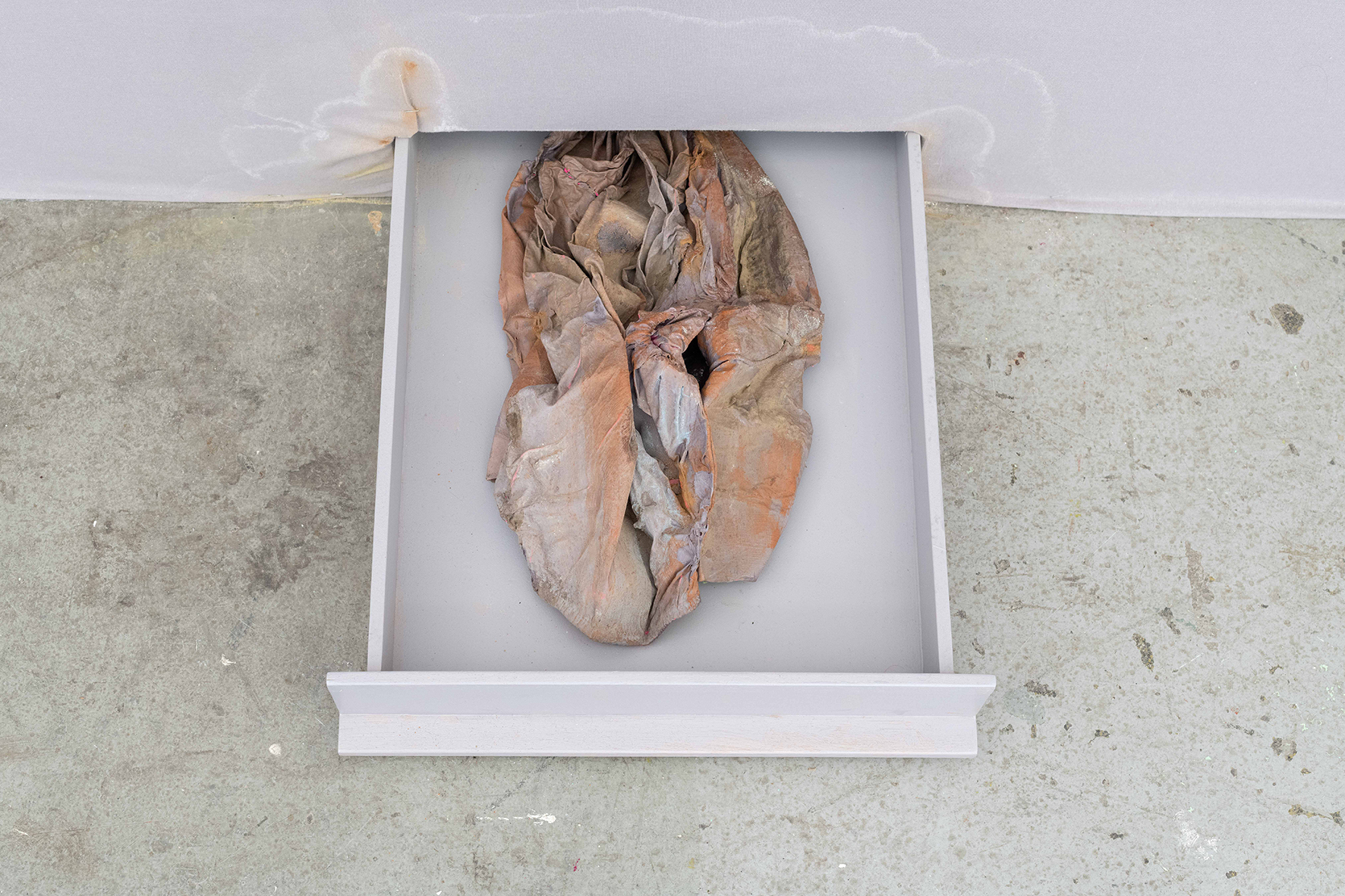

Soloshow by Swiss-Dutch artist Manon Wertenbroek at Toxi, Zürich Manon Wertenbroek constantly speaks of the body without ever representing it directly. Her practice is based on tactile contact with the material, summoning a delicacy that borders on fetishism. Leather and latex sculptures evoke the skin, sometimes crumpled, sometimes stretched by metal bridges that underline their suppleness. A meticulous and precise work that is paradoxically coupled with explicit pain: when Manon Wertenbroek pinches and twists her compositions, she imagines, for example, piercing a skin with a needle. "These different materials are like pieces of the body that I mutilate and heal at the same time," she exclaims, spontaneously summing up the sensuality of her works and the violence suggested by her techniques.Text

In English, the expression ‘to get under one’s skin’ carries a puzzling polysemy. It can be said of something or someone that irritates – sometimes until obsession – and, at the same time, it can also refer to the fact of gaining a deeper understanding of something or, even, to manage to fill someone’s mind to the point of gaining control over them. In any case, it describes a feeling that is all at once visceral and overwhelming. This is most notable when, like in Cole Porter’s song, the expression is used in reference to someone one is not able to forget or ignore.1 There, love and pain become intrinsically enmeshed, and the skin turns into the symbolical site of this emotional entanglement.

With S(k)ins, Manon Wertenbroek tackles precisely the interrelationship between these two feelings. The exhibition’s title is borrowed from a text by Jay Prosser in which the scholar reflects on skin as a memory surface. In particular, Prosser’s essay uses psychoanalysis to assert that our ‘skin’s memory is burdened with the unconscious’.2 Discussing psychoanalyst Didier Anzieu’s book The Skin Ego as well as a number of what he calls ‘skin autobiographies’, Prosser argues that traumatic (family) memories, including unconscious ones, can re-emerge, sometimes generations later, in the form of a psychosomatic skin condition such as psoriasis or eczema.3 There lies the constitutive connection between ‘sin’ and ‘skin’, as highlighted by Manon Wertenbroek in the title of her exhibition: the skin ‘re- members’.4 We carry, not only under, but also on our skin, the traces of our emotional life, and even our most guilty secrets and best repressed thoughts can suddenly burst out in the form of a relentless, itchy rash.

In her practice, Manon Wertenbroek has been exploring the duality of skin as something that singularises us and, at the same time, puts us in relation to others, a containing yet revealing organ – like a curtain providing privacy while letting the light through. Whether shaping it directly as leather or creating works that evoke it more poetically or metaphorically, she uses the image of skin as both a boundary and a point of contact, a fleshy layer that simultaneously protects and connects, to reflect on the traces left by our experiences and interactions. Though fleshy, Manon Wertenbroek’s works are usually disembodied: they are reminiscent of bodies without taking a body’s shape or volume. For it is not so much the physical being as it is the spiritual essence hidden under the surface that she seeks to uncover. Entering this exhibition, you may have had the feeling of crossing a threshold, of penetrating a deeper layer, of going, in some way, under the skin. This immersive space within the space is an invitation to scratch the surface, to peel off the cutaneous layers and to reveal, perhaps, a concealed emotional truth. The walls of the room are wrapped in brushed cotton covered with salt stains, as if the fabric were perspiring. Out of this greyish membrane, enigmatic objects emerge, both evocative and suggestively organic, like memories, nightmares and fantasies resurfacing from the depths of the unconscious, clawing their way out of oblivion and repression. There, in the back, opposite the door through which you entered, a recess in the wall accommodates two items, hung there like pieces of clothing forgotten in a wardrobe or a hide ready to be tanned. Three open drawers pierce through the room’s walls. One contains a zipper – a signature element in Manon Wertenbroek’s works – that incites you to look behind the surface. Similarly, in a second drawer, a hatch is slightly ajar, hinting at a false bottom and truths deeper than what may seem. The third one encloses a bizarre, fleshy clump, materially similar to the objects hanging in the niche and echoing the colour of the walls; an organic protuberance already too swollen for the drawer to be pushed in again. In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard described a house’s furniture and, in particular, its storage units with their doors, shelves, double bottoms, and locks, as ‘veritable organs of the secret psychological life’.5 Chests and cabinets are necessary not only because they hold our belongings and help us organise our material life, but also because they safeguard our privacy. Pulling a drawer open or peeking inside a wardrobe also means penetrating someone’s intimacy. It amounts to sounding the depths of a soul. In this room that is also a body, every object exudes double entendres, seems to conceal and reveal in equal measure and to epitomise a secret chamber that has begun to overflow, to leak through the cracks and interstices in the walls. The drawers and alcove puncturing the wall’s surface suggest furniture but they are also orifices gaping on our most repressed desires and traumas. Though intimate, this space is anything but cosy. The cushions, promise of comfort, are rendered unusable, caked with latex and fused old rags. The room’s colours are not those of a healthy, rosy flesh but, rather, of a deteriorating skin, stained with sweat and oozing fluids. It is a skin made sick by fears and secrets. Yet in its illness, the space also conceals beauty and care, apparent in the meticulousness with which Manon Wertenbroek has executed her pieces, of which she often says that she simultaneously scars and nurture them. In this room that is also a body, love and hatred are put face to face. There is pain, but there is also a promise of care.

For the artist and feminist psychoanalyst Bracha L. Ettinger, the aesthetic experience entails a therapeutic potential. She considers artists as healers who desire ‘to transform death, nonlife, not-yet-life, and no-more-life into art’.6 For S(k)ins, Manon Wertenbroek created a space in which death drive and life force, decay and eroticism go hand in hand. It is an exhibition that conveys us to an experience that is simultaneously uncanny and gestational, in which fears and pain begin to surface to be confronted rather than remaining buried and infectious. While sick, the body is still displayed here as a home to inhabit. And inhabiting one’s own body, embodying it, also means making it comfortable, homely, despite the mess that sometimes overwhelms it, spilling out of its drawers and cabinets. We are never as aware of our body as when we experience pain, when it suddenly doesn’t feel like it should. It is in these moments of alienation when our own body becomes estranged from the idea or image we have of it, that we start to acknowledge it, to be ‘in touch’ with our own self. Out of alienation emerges a possibility for connection, and for healing.

References:

1 Cole Porter, I’ve Got You Under My Skin, 1936.

2 Jay Prosser, ‘Skin Memories’, in S. Ahmed and Jackie Stacey (eds.), Thinking Through the Skin, Routledge,

2001, p. 52.

3 See Didier Anzieu, The Skin-Ego, trans. Naomi Segal, Routledge, 2016.

4 Prosser, p. 52.

5 Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, Beacon Press, 1994, p. 78.

6 Bracha L. ERnger, ‘Weaving a Woman Artist with-in the Matrixial Encounter-Event’, in The Matrixial

Borderspace, The University of Minnesota Press, 2006, p. 197. Thanks to Nicole Schweizer for pointing out this reference.

Simon Wursten Marin