Archive

2022

KubaParis

Tangible matter

Location

F2 GaleríaDate

01.04 –27.05.2022Photography

Roberto Ruiz; Sasha TamarinSubheadline

"tangible matter", a solo exhibition by artist David Benarroch at F2 Gallery, Madrid. The sculptures that are shown reflect his interest in process, movement, body, gestures and material experimentation. The artworks are mainly created out of processable materials that are in transition from liquid to solid, like: resin, latex, cement, wax, bronze, brass etc. Usually, the creations process reveal the traces of the conditions of the sculpture’s creation, and often the making of the work is embedded in the work itself.Text

One afternoon in early January 2021, David Benarroch was returning home through a Madrid still under the effects of Filomena. The streets were still covered in snow and the wider streets had barely been recovered for road traffic. White dominated the roofs of houses and cars but the pavements were a mixture of brown, grey and black. Due to the light of the street lamps, everything around them had a warm, golden tone, inherited from the Christmas season, whose decorations remained buried in piles of branches, rubbish and snow. Benarroch thought that there must be little left for the definitive thaw. A couple of days, maybe three at the most. Then the exception status that the city had gone through would be over and everything would return to normal. All that would remain of those days would be the anecdotes and the millions of gigabytes of photographs that no one would ever see again because everyone had shot them identical. In other words, narratives that only exist while they are being told, and images forgotten on the phone. Hardly anything.

Suddenly he stood there in the middle of the street, under the beam of the streetlight, his eyes wide open, contemplating an impossible idea. Immediately, with the blink of an eye, he broke the spell and started to move, staring at the ground around him. Carefully he moved forward, trying to step in the gaps left by the melting snow, taking care not to break the solid white slab, all the while looking carefully from one side to the other. He was looking for normality, vulgarity exemplified, something that did not stand out. However, he was immediately aware that the more time and intention he spent looking for it, the more distant that target would be from him, and with a final turn of his head, he made up his mind. Bending down, he picked up a piece of snow that had been left loose from the pile made by the street-sweepers. Like an iceberg torn from the polar mass, or an ashlar detached from a pyramid, abandoned to its fate on the cobblestones, it was a perfect white.

He immediately broke into a run, returning to where he had passed shortly before, retracing the path to his study. For time was now a critical factor, in fact, the most important one. At one point he slipped on the ice and almost fell to the ground. Luckily he regained his balance and, with an anxious glance, checked that he had not broken or dropped the piece of ice. He advanced a little further, always fast, but now more carefully, bearing his weight with each step to avoid another accident, nervous but firm, until he reached the door of the shop. There he had to gently deposit the piece of snow back on the ground while with trembling hands he reached into his pocket for the bunch of keys and opened the metal lock.

Once in the studio, he gathered together the ingredients and began the process of mixing them without losing sight of the white parallelepiped resting on one end of the work table. Against the wall its flickering shadow was drawn as he stirred powder and liquid in search of the perfect texture. It was a precise job against the clock. He had only one chance; there was no room for mistakes. Finally he made the decision to take the risk and gave the mixture his approval. He was afraid of being late: ultimately the most important ingredient was time.

He carefully placed the lump of snow upright on a tray and, gripping the casserole pot firmly with both hands, began to pour the viscous mixture over it. The moment the liquid touched the ice he thought he heard thunder in the street and it seemed to him that the light trembled in the studio. It would not be surprising if he thought that nature could not but rebel against the abomination he had just summoned. Still he kept up the steady flow of the liquid, which, as it fell, formed a solid layer around the patch of snow. At last, the last drops slipped off the edge of the casserole pot and he was relieved to find that he was breathing normally again.

All that remained was the last part of the process: waiting for the ice to disappear, for the snow to return to its original state, for the water to escape from the mould it had just created, leaving behind only the shape. If all had gone well, he would have succeeded in turning everything that had happened in the city in the past days into bronze, preserved forever.

* * *

David Benarroch’s work always refers to the process of creation. His sculptures are the result, record and witness of the time and gesture used in their production. Each one preserves, reveals and eternalises for the spectator the movement, strength and time that the artist used to create it.

The volume and weight of the work is limited by the physical capacity of the artist. His works are as large as he can physically handle. There is nothing in his production that he cannot move or attempt. That is the limit. In that way they are also a reflection of his own body, of his height, of his strength and, ultimately, of the solitude of his work, which involves no one else. Of the isolation of the creative moment in the studio. If sometimes we see that some works have a happier, more melancholic or more amusing tone, we can imagine that they are a reflection of his state of mind during the creative process.

His sculptures are marked by the signs of manual labour: lines, wrinkles, strokes and cracks. In each one of them we can see each phase of creation eternalised. It is geography of the process that has become an essential part of the work. They are like sedimentary strata that record the different moments in the creation of this particular sculpture.

Benarroch works mainly with non-natural materials. As in other aspects, he seems to be fighting against the commandments of historical sculpture. There are hardly any pieces of wood, but never, for example, stone, and the traditionally noble material of classical sculpture. Metal, yes, especially from industrial use, and, above all, resin, fibreglass, latex or cement. Moreover, this allows him to accentuate the interplay between what the spectator sees and what things are really made of. There is a pretended confusion between hard and soft, light and heavy, fragile and resistant.

For the same reason he always seems to be looking for the limit point of equilibrium of each sculpture. As if they were at an awkward point, on the verge of falling or in danger of being knocked over by a brush or a gust of wind. Questioning in this way the most basic thing a sculpture should do: to remain firm in space.

The references to classical sculpture go as far as the plinth. Many have a structure, sometimes a found object of everyday use, which reminds us of it in an ironic way. In this way he acknowledges its existence but questions its nature. Moreover, in contrast to the commonplace of the round bulk, Benarroch gives the impression that he tries to embrace all directions with elements that emerge from the main volume in all directions.

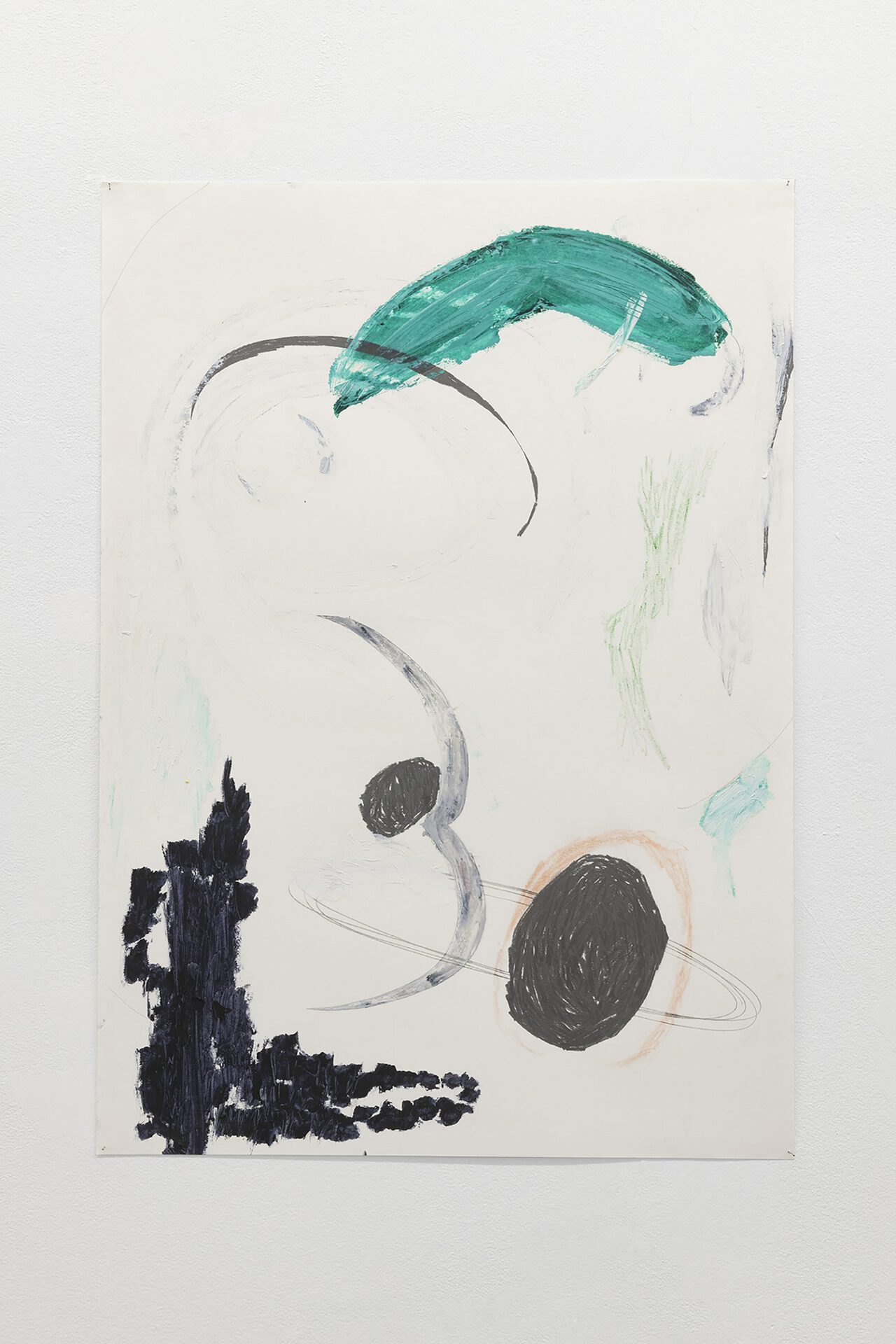

At the same time, David Benarroch understands drawing as an intimate medium. The working method is the same as in his sculptures, but by making the gesture on a smaller support, closer to the body, lighter and closer, the result (like the process) is closer and more conceptual.

Let us understand Benarroch’s work as that of an alchemist. Alchemy, that branch of pre-science between chemistry, philosophy, magic and mysticism. In the same way that it literally turns liquid into solid, it also aims to eternalise a particular moment, to solidify time, a particular moment, and preserve it forever. The lack of a frame or pedestal serves to free the work from the idea of the artistic object.

However, during the process, something always happens that is neither foreseen nor measured, that cannot be calculated or anticipated. That is the risk and its motivation: to find that which has a spiritual aspect, practically, the transmutation of time into matter. During this work, a negotiation is established between the artist and the material: the former wants to get to a point, but has to see how far the latter will allow it. Along the way there is energy, surprise, accident and chance. It is a cycle and a search and the result creates a place for contemplation where time and space come together.

In order to understand David Benarroch’s work, it is essential that, formally, these works take us back to the first two examples of the use of sculpture: the monolith and the stele. Vertical or flat forms that served as an element of commemoration and remembrance, of preservation of an event or person against the passage of time. In this case they are practically a monument to a specific instant, to a precise encounter between material and artist. They are the celebration of an instant.

Joaquín García Martín

Joaquín García Martín