Archive

2022

KubaParis

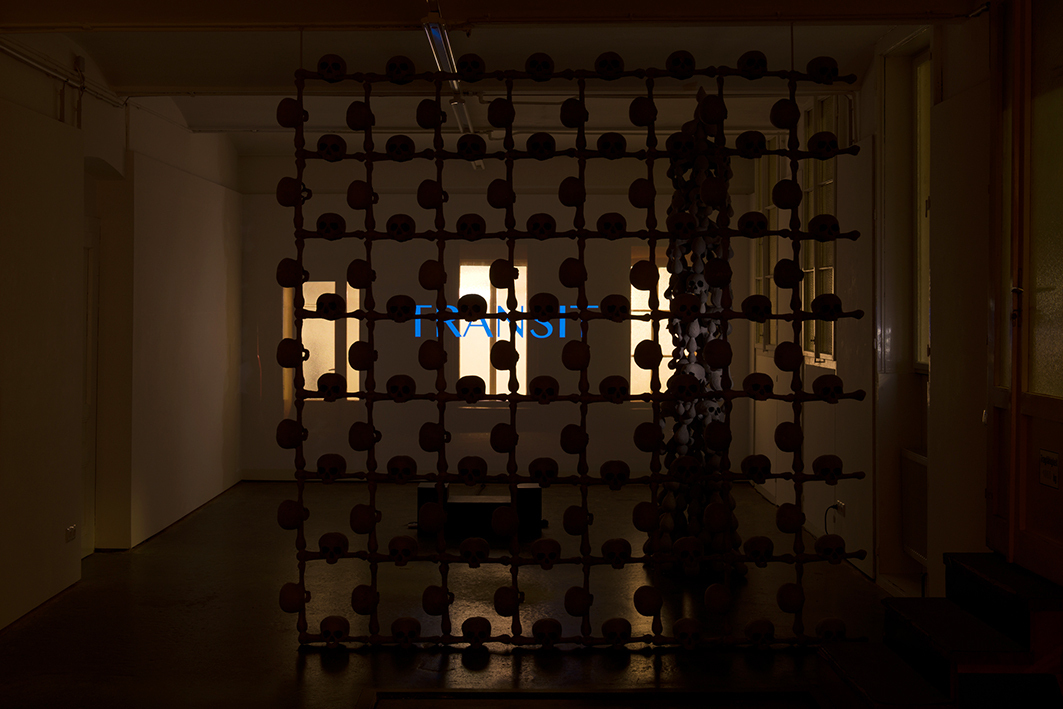

TRANSIT

Location

ClubclubDate

21.03 –28.03.2022Curator

-Photography

Stefan LuxSubheadline

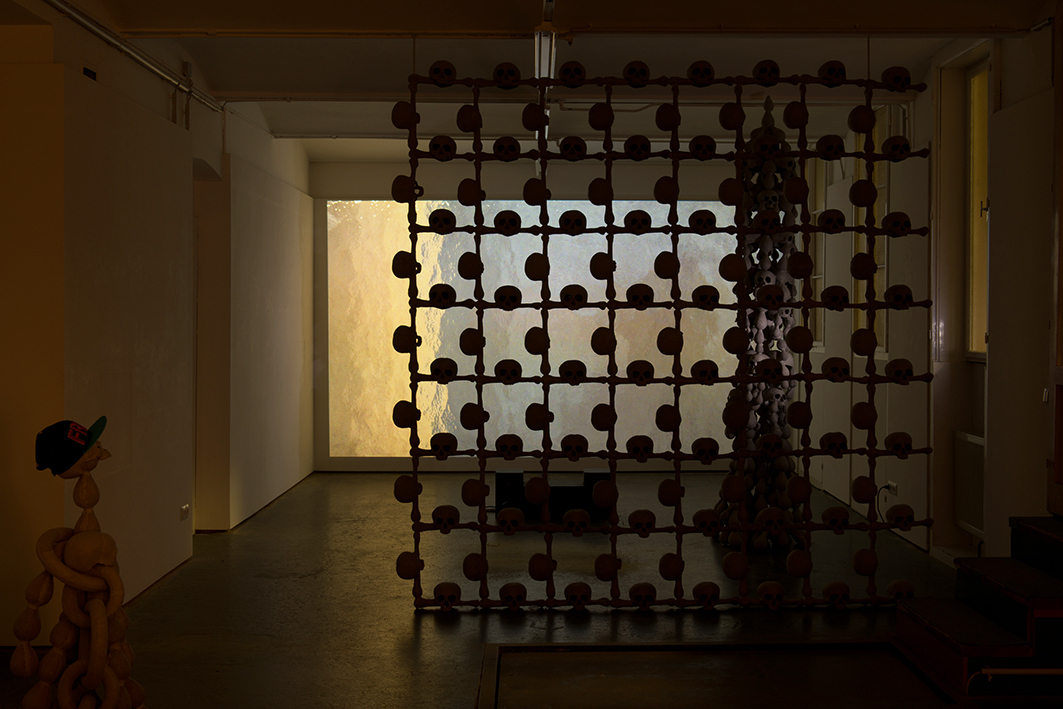

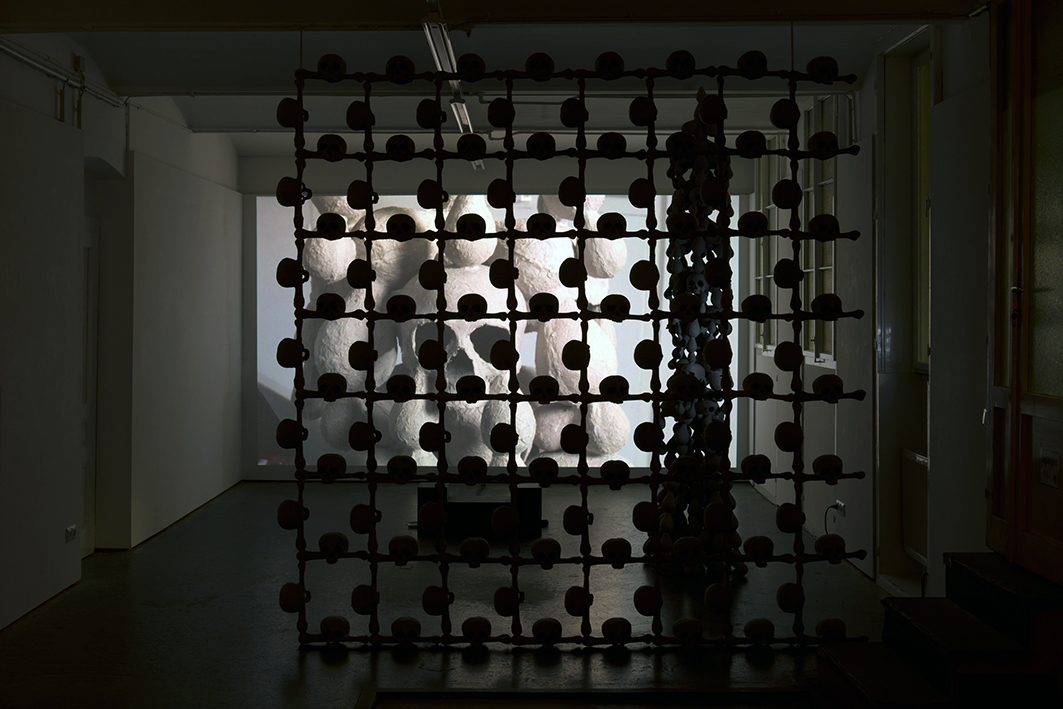

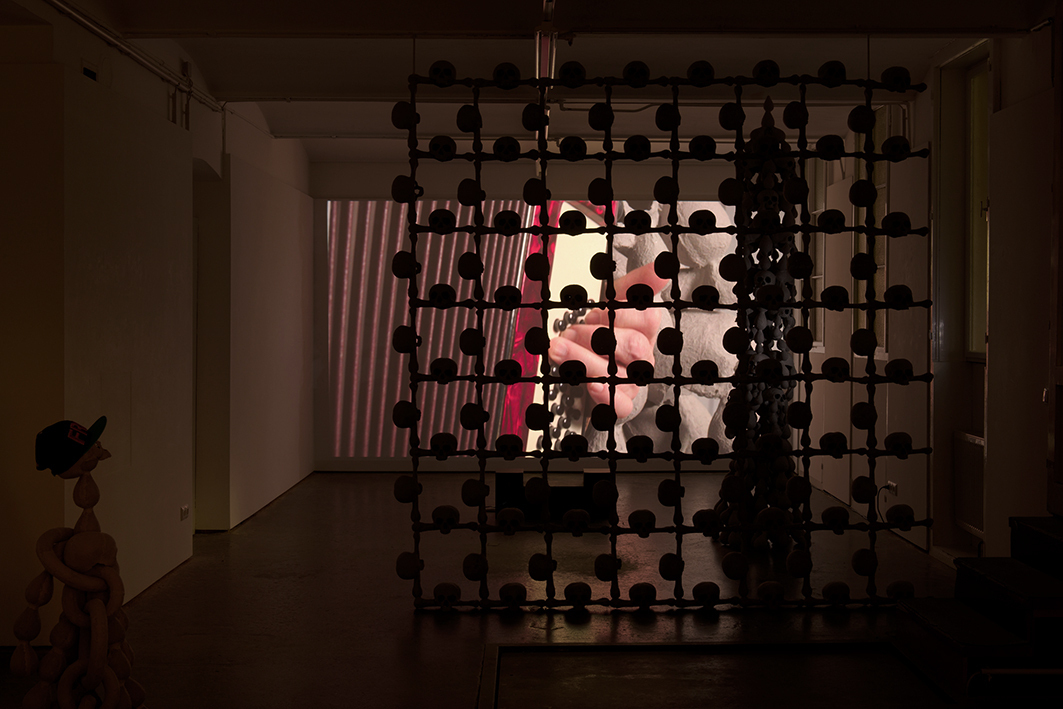

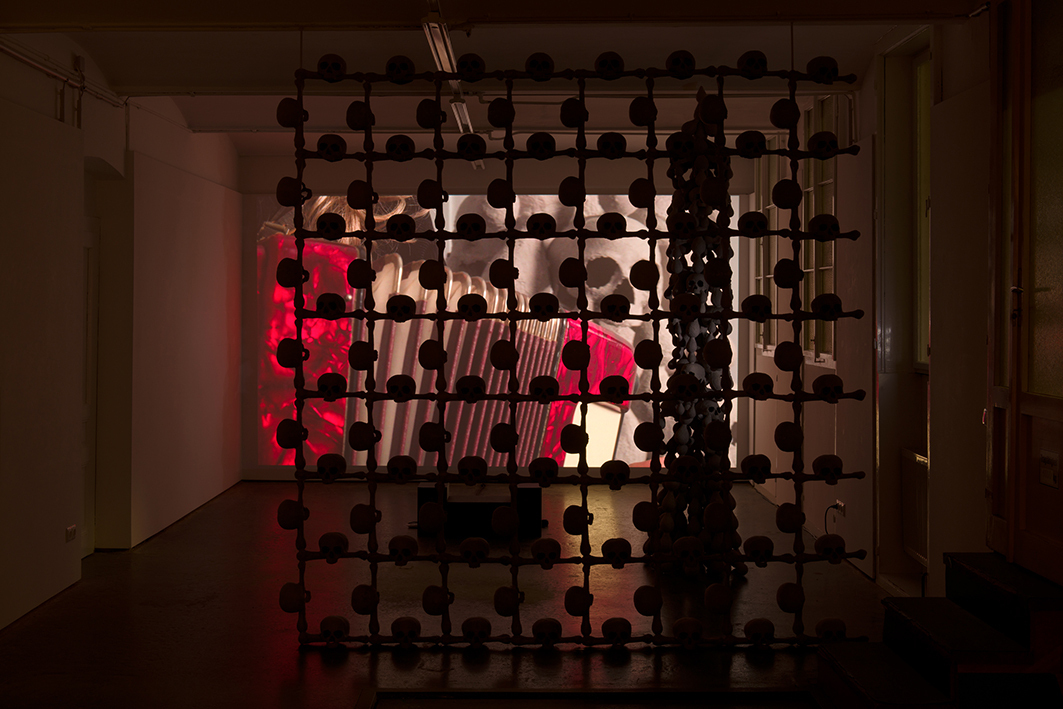

TRANSIT is a cooperative production by Ulrike Johannsen (sculpture) and Stefan Lux (Video). Yuki Higashino contributed the text.Text

There is a painting of Mary Magdalene by Titian. She is contemplating the sky, her long, wavy hair loose and cascading over her shoulders and chest. In front of her is an open book resting on a skull. This woman, the chief disciple of Jesus and the leader of the early church, according to the Gnostic tradition, is often depicted with a skull. Presumably as a memento mori but after being paired in so many pictures, she developed a strange familiarity with this most macabre of objects. Being the primary witness to the resurrection, death was her friend. There is another painting, this one by Georges de La Tour, where she has a skull on her lap and rests her hand on it as though it was a cat. Tender. The picture has that typical La Tour stillness, and the skull is the most animate presence in it. Its upward gaze mirrors Titian’s Mary Magdalene and with its jawbone missing, it perpetual laughs. It’s a funny skull.

In the video by Stefan Lux, we see long blond hair and skulls. Both the hair and the skulls belong to Ulrike Johannsen. The hair is hers and the skulls her sculptures. She is playing an accordion. She is singing.

She is singing “Wenn ich mir was wünschen dürfte” (“If I Could Wish for Something”) by Friedrich Hollaender, made famous by Marlene Dietrich. It is a song about the futility of fulfilled desires. The vacuity of granted wishes compared to the sweetness of expectation. That thing you wanted was worth it only when you were longing for it.

She is singing. She is in her studio. We are in her studio.

We are in her studio listening to lines like “Ich schaue in die Stuben durch Türn und Fensterglas” (“I'm looking into living rooms through doors and windows”) which is exactly what the camera is doing. The camera is outside looking into the room we are in right now, watching the footage it took. It looks in but cannot see anything because the glass is frosted. It can only capture the warm yellow light, diffused and soft. Enticing. And then it is inside. But it is already looking out through the same frosted glass. Outside is night. It is blue.

Does it already want to leave? Perhaps. This room it so wanted to enter is full of skulls and inhabited by a woman who sings of the pointlessness of fulfilled wishes. She conjures these cousins of La Tour’s droll skull by the dozens. How beastly. But it is night out there. The song fades. In the end, the camera is back on the street, focused on the pale reflection of the warm yellow light of the room it just left on the window of the car parked outside. A Ford Transit.

Hollaender was a Jew, like Mary Magdalene. A successful film and cabaret composer in Berlin, he was forced to emigrate in 1933. He found himself in Hollywood and had an illustrious career there, teaming up again with Dietrich.

He went back to Germany in 1956 though. And settled in Munich of all places. That is mindboggling. Why would anyone, let alone a Jew, do that? The stench of death couldn’t have cleared yet. Skulls strewn across its blood-soaked earth. I can only speculate. The cultured and secular Jews of Europe really, really wanted to assimilate, to be admitted into that enlightened civil society they thought existed across the invisible threshold, as inviting as the yellow glow of a warm room seen from the street in a cold night. But that room was full of death and destruction in reality. That thing they wanted turned out to be night. Europe was attractive to Jews only when they were wishing for it. Could Hollaender not let go? Also, he wasn’t the only one who went back. Were they chasing the pale reflection of that non-existent society into which they wanted to assimilate?

Paul Celan wrote, “A man lives in the house he plays with the serpents he writes / he writes when dusk falls to Germany your golden hair Margarete,” in Death Fugue. He wrote:

Ein Mann wohnt im Haus der spielt mit den Schlangen der schreibt

der schreibt wenn es dunkelt nach Deutschland dein goldenes Haar Margarete

Dein aschenes Haar Sulamith wir schaufeln ein Grab in den Lüften da liegt man nicht eng

Er ruft stecht tiefer ins Erdreich ihr einen ihr andern singet und spielt

A man lives in the house he plays with the serpents he writes

he writes when dusk falls to Germany your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Shulamith we dig a grave in the breezes there one lies unconfined

He calls out jab deeper into the earth you lot you others sing now and play

Music, hair and corpses. It is an enduring image. It so happens that bones and hair are the two things that last the longest when we die. They are the least transitory of our constituents, even though we shed hairs regularly. But bones are our cores, while hairs are the extremities of our body. Is their longevity, well after our passing, a grim form of inside/outside dialectic? Maybe. But we will be too long gone to find out what happens when they meet without any flesh obstacles, even though, technically, they are us.

Yuki Higashino

Yuki Higashino