Archive

2022

KubaParis

Circular gestures

Location

unanimous consentDate

26.03 –07.05.2022Curator

Alejandra Monteverde & Alexandra RomyPhotography

Philip UllrichSubheadline

with Camille Dumond, Luisanna Gonzalez Quattrini, Tomas Maglione, Jacopo Mazzetti, Raul Silva, Zoé de SoumagnatText

Circular time, or endless recurrences, suggest that all things iterate eternally. Circular time has no end, it is perpetually in motion. In The Gay Science1, Nietzsche develops the idea of the circle of time or eternal return under the name of amor fati - the love of fate - expressing that since everything recurs infinitely in life, we shall love and embrace our fate, our infinite ways of becoming and chaos. Circular time is by definition the contrary of progress, which belongs in the realm of linear time. Progress cannot be drawn as a circle, but rather takes the shape of a line. In Western societies, progress is a way to reach a result: an obsession with perfection, forcing us on a path of advancement. We have no choice but to continuously upgrade ourselves, we must move forward, fast. It is a fashionable human aim to – ultimately – reach Paradise, and the neoliberal capitalist economies trigger us no differently. As our bodies become commodities, we are pressured to grow, consume and waste2.

But what if rather than categorizing time in three distinctive and extraneous units – past, present, future— we would situate ourselves, with our bodies, inside time. For the people living in the Andes, time is built differently. The past is what we can see in front of us, and the future is something that is situated behind our backs. Andean thinking literally embodies the time, using the word „eyes“ to translate the past and „back“ to translate the future. Now the perspective has changed, we are still moving, but walking backwards, observing the past and recognizing the future as something we can’t possibly see, unless we turn our head over our shoulder and have a quick glance at it. In the Andean thinking, time – alike space – is a house, a place we inhabit. It is a heartbeat, the breathing of air, the constant back and forth of the sea or the perpetual alternating between day and night, a cyclic repetition that corresponds to the order of the cosmos. Time is not a quantum that can be expressed in mathematical term or possessed, but rather is considered in its physicality, either according to its quantitative characteristics, like density, weight, or to its relational aspect, for example in connection with the importance of an event or celebration3.

While in Occident we have invariably been going forward into the future, colonized it with our ideas, shaped it with what was in our heads4; there is no idea of progress in the Andean conception of time. What in Occident exists temporally forward in the future, is – in Andean thinking – behind. This is why there is no need to make any projection, no need to have any „desire-to become“, there is simply a need of being5.

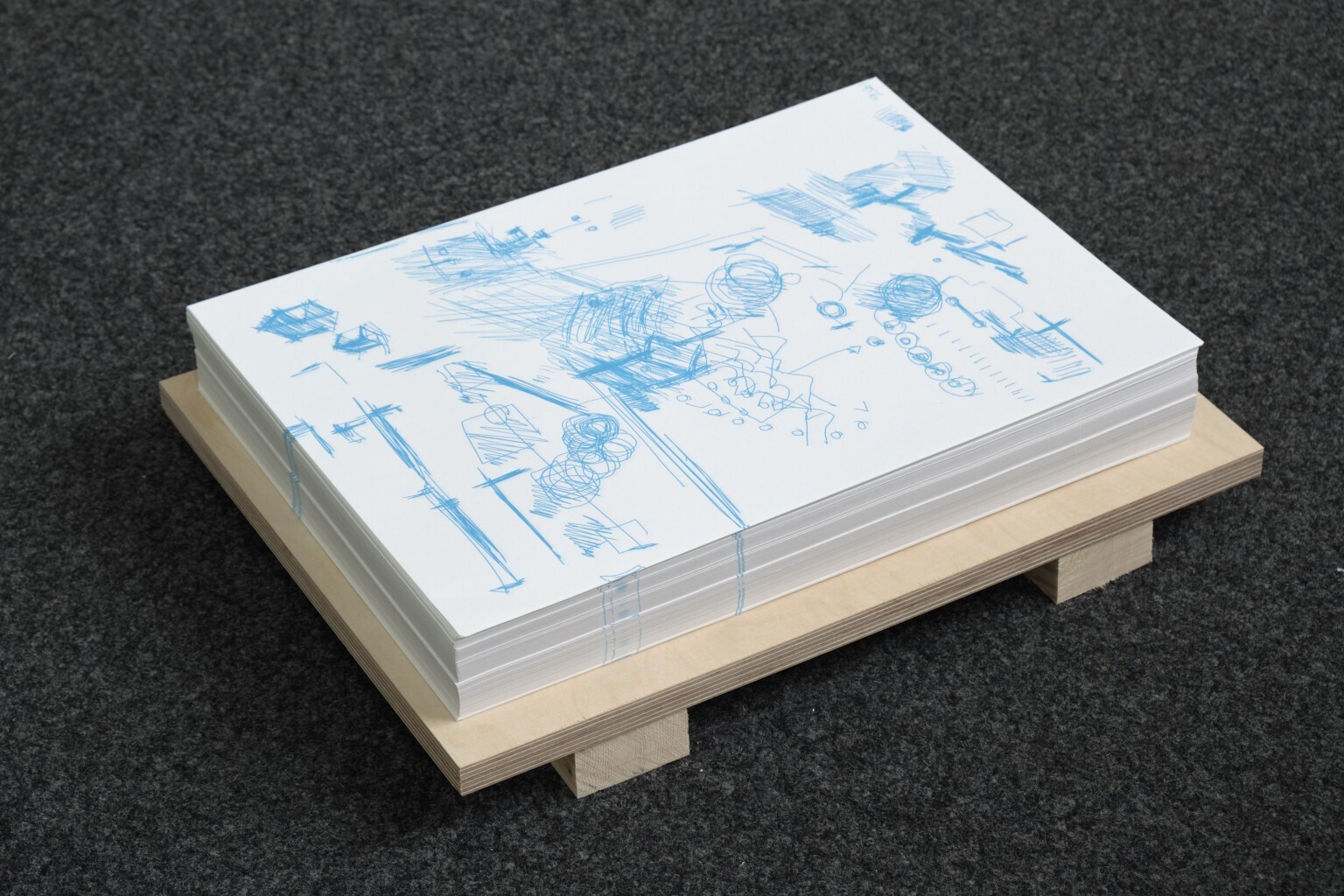

In his video-performance, For future‘s sake, Raul Silva addresses our will for progress. The work is accompanied by a drawing that the audience is welcome to take. During the performance, Silva achieves an automatic drawing while reading a semi-fictional family testimony, speaking about the impossibility of changing the present from the trans- formation of a concrete event in the past. Silva keeps reproducing the same drawing until the audience realizes that this drawing is exactly the same as the one they are holding. In Tomas Maglione’s video, When the world dissolves, we follow the journey of a round feather object spinning without any agency in the streets of Buenos Aires, ultimately drawing infinite circles. Further, Jacopo Mazzetti’s round sculpture addresses a feeling of circularity. Its materiality that combines industrial lathe and a sunflower seems to connect our industrial being with a kind of astral nature in an infused paradox. Children, the crystal quartz engraved sculpture belongs to the lineage of the ancestral stones which were made to tell stories, such as the altar of Coricancha: a golden plate carved to represent the Andean cosmology6.

Embodied gestures and movements are at stake in Zoé de Soumagnat‘s painting and Camille Dumond‘s sculpture. While de Soumagnat‘s legs seem to encircle a duality, a desire to move whilst also being constraint, maybe an appeal to change direction or look somewhere else; Dumond‘s mobile slightly moves within the air, in a continuous motion, while – at the same time – elegantly staying put. Luisanna Gonzalez Quattrini’s paintings, on the other hand, take us to a place that erases any idea of time and demands us to stand still for a while and look thoughtfully at what lies ahead; subtle color surfaces that make visible a world in front of our eyes that deserves our attention.

Circular gestures is an attempt to think of time with our bodies, to situate ourselves in time as a space, to embrace or accept the circularity of life with a certain motion or magnitude. Circular gestures means moving in circles.

1Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, 1882, IV, §341.

2Josef Estermann, Intercultural philosophy / Andean philosophy, Intercultural Theology, Andean Theology, An anthology, International school for intercultural philosophy, 2021, p.127.

3The entire paragraph refers to Israel Arturo Orrego Echeverría, Ontología relacional del tiempo-espacio andino: diálogos con Martin Heidegger, Bogotá: Universidad Santo Tomás, 2018, pp 131-139. 4Ursula K. Le Guin, Dancing the Edge of the world, 1989, pp.142-143.

5Israel Arturo Orrego Echeverría, op cit.

6Replica of the Inca Golden altar of Coricancha, Church of Santo Domingo, Cuzco, Peru.

Alejandra Monteverde & Alexandra Romy