Archive

2022

KubaParis

waves

Location

CosarDate

28.01 –17.03.2022Photography

B.S.Text

Berit Schneidereit

Waves

“The sun had not yet risen. The sea was indistinguishable from the sky, except that the sea was slightly creased as if a cloth had wrinkles in it. Gradually as the sky whitened a dark line lay on the horizon dividing the sea from the sky and the grey cloth became barred with thick strokes moving, one after another, beneath the surface, following each other, pursuing each other, perpetually.”

Virginia Woolf, The Waves, 1931

Boundaries between prose and poetry become blurred in Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves, the title of which Berit Schneidereit borrowed for her solo exhibition at COSAR. Six inner monologues interweave to form the facets of a narrative, generating a continuity rather than a self-contained story. Virginia Woolf herself referred to the work as a “play-poem.”

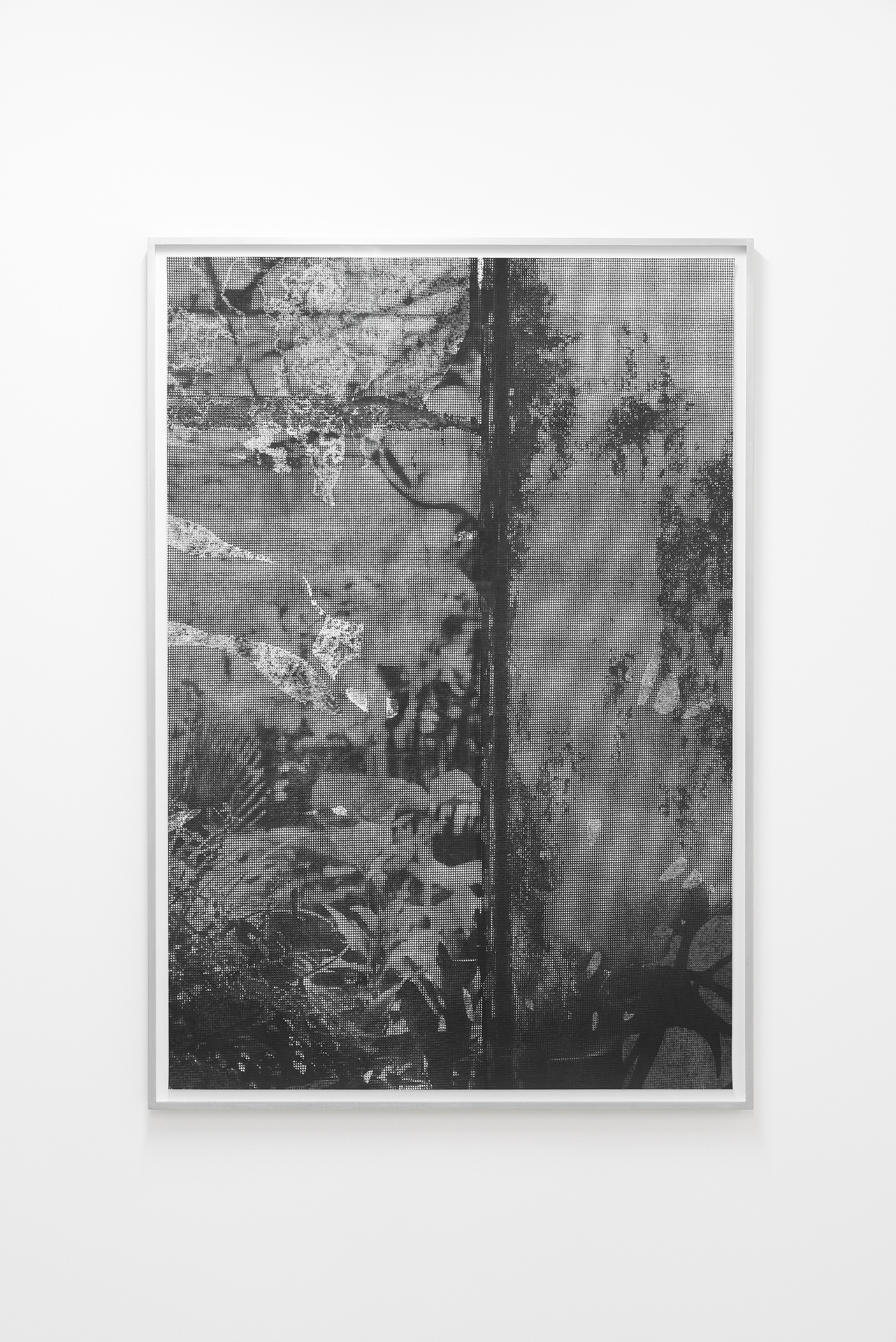

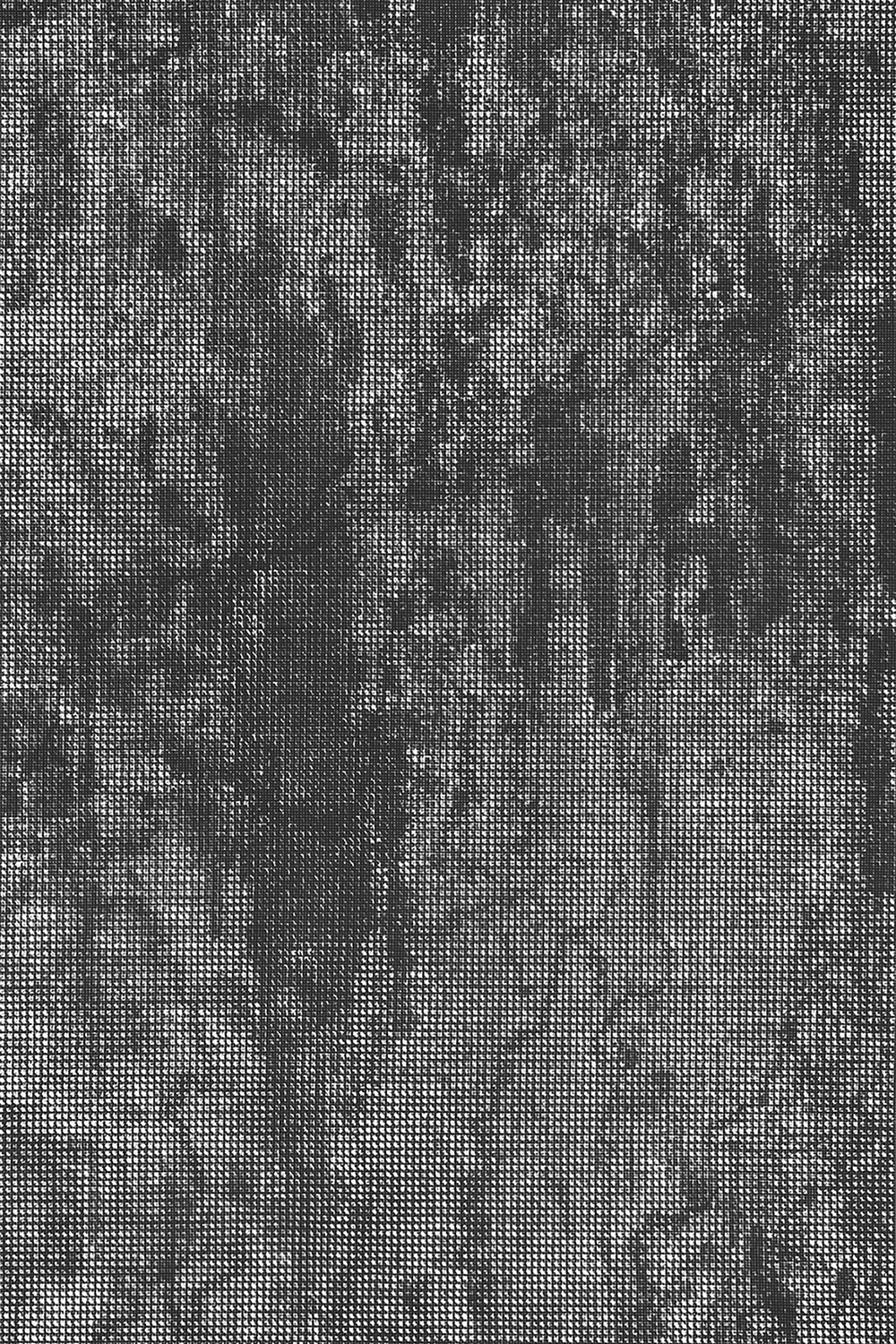

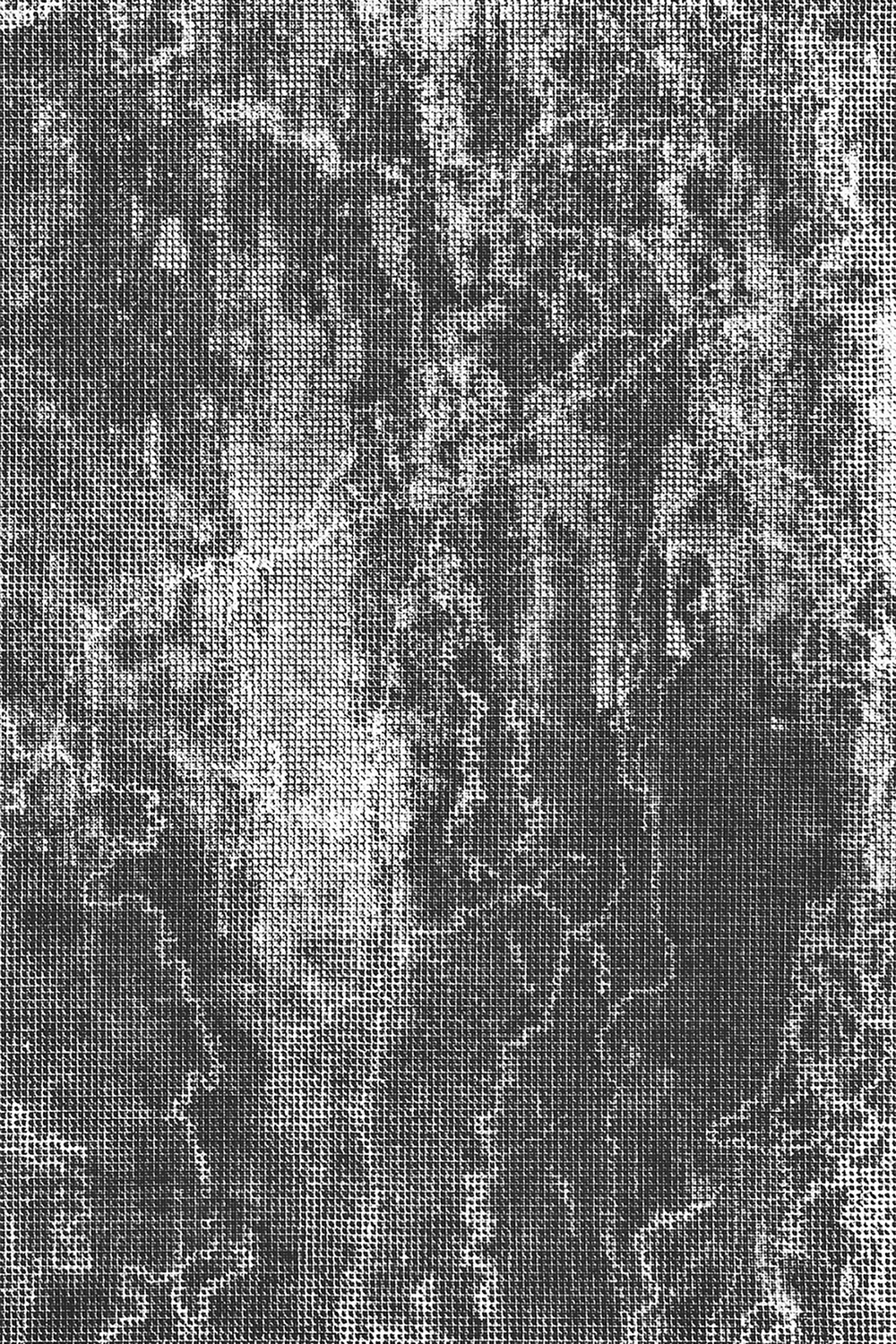

Berit Schneidereit’s photography similarly blurs boundaries, constantly moving between different dualities: color and black-and-white, fiction and documentation, painting and photography, positive and negative. The two series developed for the exhibition face each other as polar opposites, which nevertheless build on two approaches that Berit Schneidereit has been working on for a long time. The large-format, black-and-white photogram series retouch is based on the artist’s archive, which she continuously maintains and expands, especially while traveling. On her travels, she searches for places that harbor an ambiguity: urban settings where nature and culture merge and intersect. Humans play no role in her images. They are more focused on the interplay between plants as a kind of artificially assembled nature and constructed forms like grids, visual barriers, and other structures that hinder one’s gaze.

Berit Schneidereit’s unique negotiation of the photogram technique continues her concern with structures and their influence on the perception of the image’s visual field. She covers her photographs with lattice structures or meshed fabrics in the darkroom that register on the photo paper’s light-sensitive surface as a testimony to the material. In so doing, she transforms a digital image of reality into a newly constructed imaginary space that gives the body of work it distinctive character. One can’t quite tell what lies above or below—even less so what is a found object and what is a constructed surface. Berit Schneidereit plays with the optical processes of vision, baiting the eye that wants to order things but ends up jumping back and forth between two sides of a net. To intensify this play, she also worked with the inversion of positive and negative space, a pillar of photography as fundamental as it is effective. She juxtaposes the same “image” in light and dark, thus underscoring the explicitly conceptual approach of her research.

If her earlier works were about drawing the viewer into paths between individual images, she entirely dispenses with the effect of depth here. Surface, form, and materiality take the place of perspective and spatiality.

The second series in the exhibition also picks up on this train of thought. Berit Schneidereit encountered the cyanotype technique on a grant to work in Mallorca while she was looking for a way to expand her photography-based concepts beyond the darkroom and the associated large technical equipment. In this early photographic process, the medium was photosensitized with iron instead of silver, while the exposure was traditionally done with sunlight. Here, Berit Schneidereit also works with photograms and grid-like elements placed on the photosensitive paper. Fabrics hover in the image as if captured mid-flight. They suggest traces of movement in themselves and conceal their protracted process of light exposure. They present a dark blue to white color spectrum in all of its gradations, dominated by iron-oxide blue and warm yellow. In a painterly gesture, Berit Schneidereit recently introduced bleach into her production process, which she applies to exposed paper in various ways. This partly effaces the images’ three-dimensionality, erasing the color and rendering the process of flattening visible through the blotted traces of the bleaching agent.

In The Waves, Virginia Woolf writes, “the light struck upon the trees in the garden, making one leaf transparent and then another.” Berit Schneidereit uses light to produce transparencies between what is there and what becomes visible, between reality and its impression, between surface and depth.

Leonie Pfennig

Leonie Pfennig