Masha Kovtun

Endless Path to Sunset

Masha Kovtun at stone projects

Advertisement

Masha Kovtun at stone projects

Masha Kovtun at stone projects

Masha Kovtun at stone projects

Masha Kovtun at stone projects

Masha Kovtun at stone projects

Masha Kovtun at stone projects

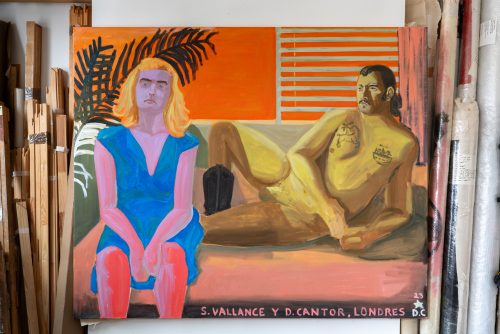

Masha_Kovtun_5AM_2024

Masha_Kovtun_Burning_Poplar_Fluff_2024

Masha_Kovtun_The_sound_of_falling_stars_2023

Masha_Kovtun_The_sun_will_rise_and_we_will_try_again_2024

Masha_Kovtun_Theatre_of_the_war_2022

Masha Kovtun in conversation with Kaspars Groševs

Masha: Hi, Kaspar! I still haven’t finished the paintings. I thought I could send them to you on Sunday. Is that okay? The paintings show a figure turning and looking at the viewer. They continue the theme of the “European dream” or “looking west” that I addressed for my diploma work. “West” can be sunset and “east” can be late evening.

Kaspars: Heeey! Oh, that sounds nice, I can already see your shimmering colors! What do you imagine when you say, “European dream”?

M: In my diploma work, I focused on the metaphorical concept of “євроремонт” (European reconstruction) with an emphasis on how the concept of Europe is fixed and reflected in the internal space of Ukraine and how it coexists with the ideologically charged material dimensions of the post-socialist state. This continued my long-standing interest in exploring Ukrainian murals, which depict views of European cities and are a common interior feature of many apartments in Ukraine.

These paintings on the walls overlooking European cities represent for me the representation of a dream - a view that is as if within reach yet separated by an imaginary wall. One can easily recognize in them the burden of “evroremont” and dreams of new facades behind which a new European reality will grow. It is an escape into an illusion, into a dream life surrounded by backdrops.

The presentation of my diploma was a performance where the entire story was created by text that started with sentences: “I looked at the sunset for so long that my eyes started to water. It felt like walking down a wild path, overgrown with tall grass, where no one had ever walked before.” - Those sentences are the best description of the paintings I’m working on now, where the figures exist in a liminal space, balancing between beauty and brutality, shadow and light, home and foreign lands.

Do you know what is евроремонт? Do you have that concept in Latvia too?

K: Yes, we have that too - “eiroremonts”. It has seriously screwed up the apartments in Riga, so many old beautiful wooden parquet floors have been lost. It’s all laminate now, sadly. My flat has both parquet and light grey laminate which is even more fucked up and I have an “office ceiling” in my kitchen which is starting to fall apart because of the cheap materials. Do you have images of those murals? What do you think of carpets on the walls? My grandmother had carpets everywhere and it’s funny that among soviet blockhouses there are still these metal bars for whipping your carpet. What’s your relationship with that side of interior design history?

M: I remember these carpets from my childhood, as they dusted the walls near my bed.

For many Ukrainians, including my parents, carpets are a reminder of the harsh Soviet past, so instead there are paintings on the walls with views of European cities.

I’m thinking of naming the exhibit “Burning Poplar Fluff”. When I googled that name, the first picture I saw was of Riga. Did you also set fire to poplar fluff as a child?

K: Hmmm, I can’t really recall, but Latvians simply love burning the old grass from the previous year in spring. “Eiroremonts” to me seems somehow like this low-budget consumer dream to live “like in Europe”, but here for most people I think it rather means “spend like in Europe”. Maybe Ukrainians have a more ideological and idealistic view of Europe which is completely understandable in the context of war, it’s about the direction away from all the horrible soviet and Russian world trauma. From my geographic location, I can feel so deep the pain of older generations who went through all that crazy ussr time. Of course, they want to live like in Europe (or at least “evroremont”) which was taken away from them! Do you feel the soviet trauma present in Czechia? What’s your favourite Ukrainian artist from history?

M: have been living in Prague for 10 years now and because my art academy studies were in the Czech Republic and not in Ukraine, my knowledge of Ukrainian art was taken from Google and my family’s artistic interests.

For example, my grandmother had a copy of Aivazovsky’s painting of a ship hanging in her kitchen. By the way, this is one of the first paintings that I repainted, my grandmother still has this drawing. And one of my mother’s favourite artists is Malevich. My mom often repainted his paintings to order. All I knew about these paintings was that they were painted by Russian authors. Who would have thought at the time that both artists were Ukrainian? A great example of Russian colonization of Ukrainian art.

Now I can’t say if I have a favourite Ukrainian artist. But I like the paintings by Marija Prymachenko. In primary school, I learned Petrykivka painting, which is a Ukrainian decorative and ornamental folk painting. I also like contemporary artists such as Nikita Kadan. Around 2010, he and his art group R.E.P. did a couple of installations called “Euro-renovation”.

The trauma of soviet colonization and past communist life is very much felt in the Czech Republic. I recently saw a signboard “Best-selling apartments: European quality in Prague”. I think that the dream of a European Union is related to the fact that the countries that were colonized by the Soviet Union have no choice. On the one hand Western capitalism with its “modern, quality materials”, on the other hand, the Soviet dictatorial past and the fear of modern Russian occupation, as it is happening now in Ukraine or Georgia.

What do you think about the name of the show Endless Path to Sunset?

K: It’s interesting that in the 2013 Venice Biennale, the Georgian pavilion was dedicated to the kamikaze loggia - extensions to block house buildings that are used as terraces or even natural fridges. I’ve seen some in Riga. It’s also another example of reaction after soviet collapse, on the verge of law, using all available materials and means. At the pavilion, there was Nikoloz Lutidze’s performance called “Euro-renovation” where he was renovating the pavilion’s space in the style of “evroremont”. In his opinion, this trend showed that we didn’t do any attempts to analyse our inner layers and instead focused on a new layer. I think for many people in Latvia the war finally opened their eyes to the failure of “integration” of the Russian-speaking population and the fact that we are still deeply entangled with the remnants of the empire. Will we ever reach sunset? Will it still be there when we come to witness it? Hopefully, it’s not a completely endless path.

M: During the full-scale Russian war in Ukraine, there is a famous sentence that is said by both civilian people and the Ukrainian military. It goes, “The sun will rise, and we will try again.” I feel so much pain in this sentence and at the same time hope.

Oil paint is love for me. I’ve tried painting with acrylics, but I think many artists will realize that it’s impossible to compare. With oil paints, you can convey colour as it really is. In my painting, colour is very important to me. I also paint with a dry brush, a technique I found after drawing with pastels for a long time. I think that with acrylics I would not be able to convey this technique. I also don’t use black and white paint.

Painting has not been my main medium all the time. It was only after the full-scale Russian invasion started that I found myself in this medium because it is the best way for me to convey what I felt about the war in Ukraine.

K: Who are the people in your paintings?

M: These are friends. I often take pictures of people and draw them but in my own way. Often, I draw different faces. Different backgrounds, whatever comes to mind. I also really like your work; I think there is a similar melancholy in our work. And also, the colours! If I get the opportunity to do a duo exhibition, I would love to have an exhibition with you.

K: Thank you! I would also really love an exhibition with you! I also sometimes like painting friends, I think the community aspect in art is quite important, not only art but also different other communities. Where do you see yourself in these different community intersections?

M: I don’t know, to be honest. I like that contemporary art is closely related to music, for example. I like to draw covers for albums, and I also like to work together with musicians, like in my last performance work where I had Johannes Tröstler do the music.

K: How do you feel as a part of the Ukrainian community in Czechia?

M: Before the full-scale Russian invasion, I didn’t consider myself in the Ukrainian community because I was mostly in a Czech environment.

Now every time I hear Ukrainian speech, I smile and sometimes join the conversation. It just gives me a warm feeling to meet Ukrainians. Because I miss my home very much.