Tamara Goehringer, Thilo Jenssen, Daniel Stubenvoll

um fragile Affären

Project Info

- 💙 WAF Galerie

- 🖤 Tamara Goehringer, Thilo Jenssen, Daniel Stubenvoll

- 💜 Ramona Heinlein

- 💛 Philipp Pess

Share on

Daniel Stubenvoll & Tamara Goehringer, Installationsansicht WAF Wien, Fotocredit © Philipp Pess, 2025

Advertisement

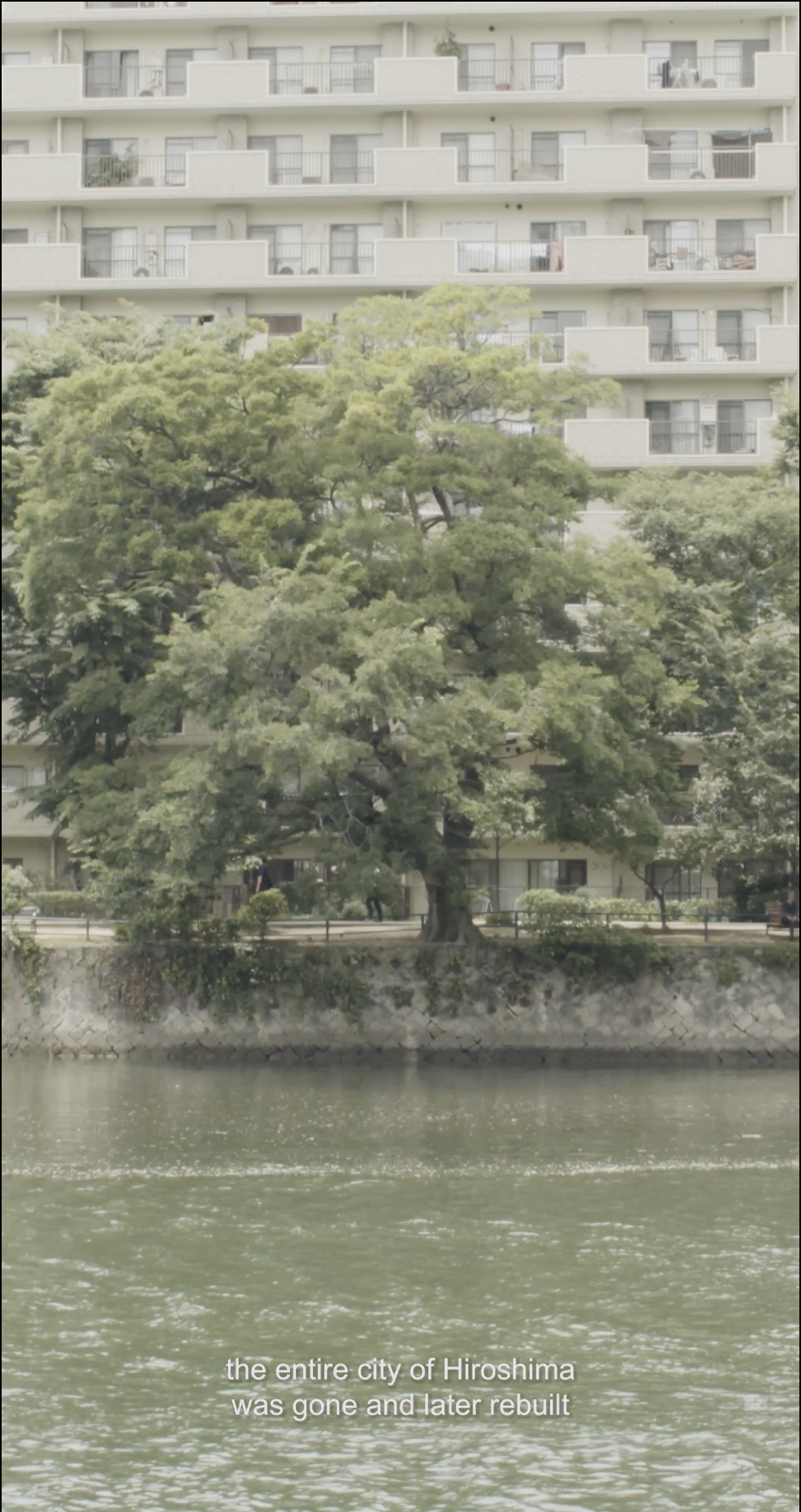

Videostill "Hands and Feet on the Street" © Daniel Stubenvoll, 2025

Videostill "Hands and Feet on the Street" © Daniel Stubenvoll, 2025

Daniel Stubenvoll, Installationsansicht WAF Wien, Fotocredit © Philipp Pess, 2025

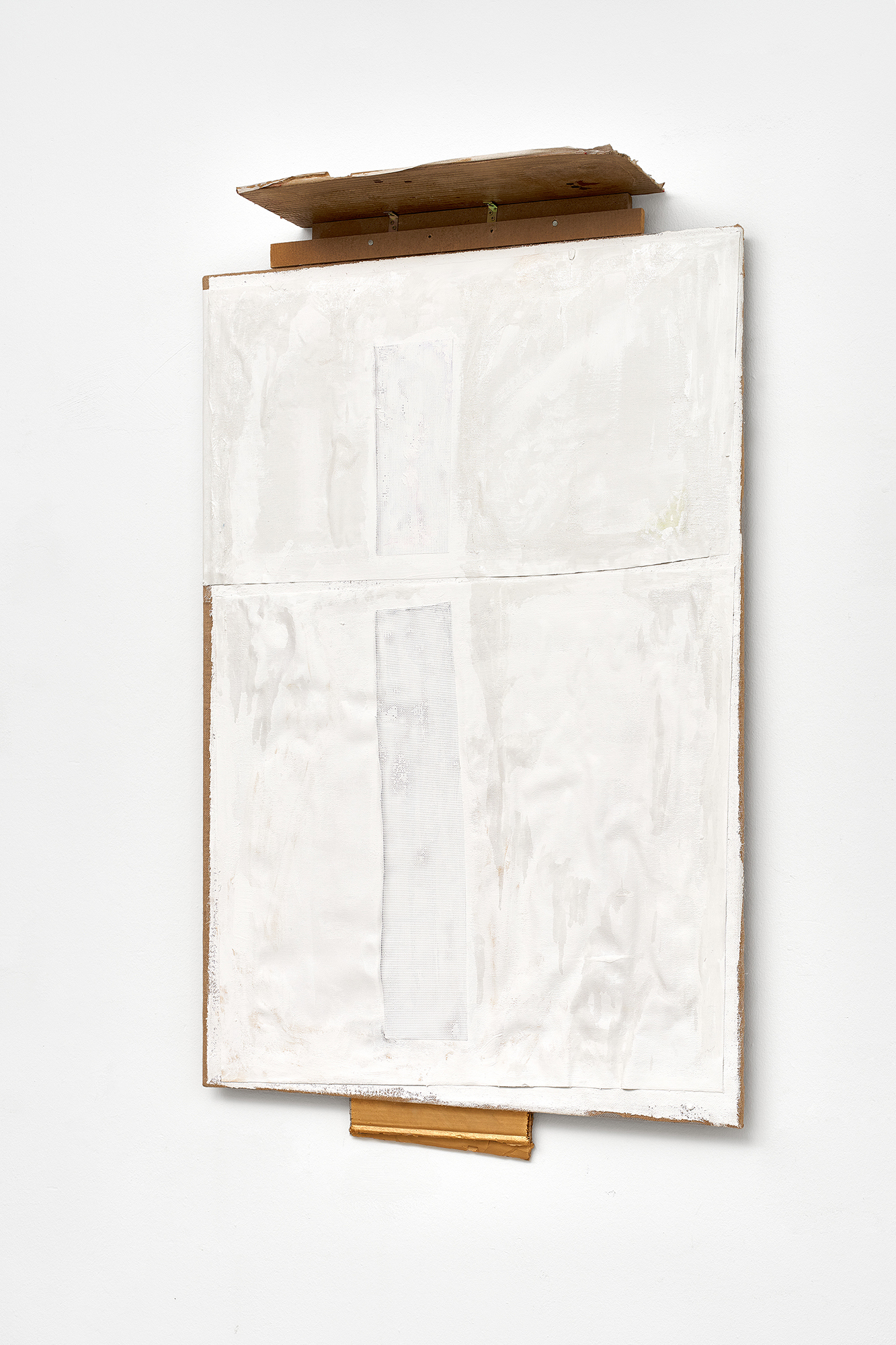

Daniel Stubenvoll – In ruins (Triumph), Fotocredit © Jens Gerber, 2025

Daniel Stubenvoll – In ruins (Horizon), Fotocredit © Jens Gerber, 2025

Daniel Stubenvoll – In ruins (it leaks), Fotocredit © Jens Gerber, 2025

Daniel Stubenvoll – In ruins (Columns), Fotocredit © Jens Gerber, 2025

Thilo Jenssen & Tamara Goehringer, Installationsansicht WAF Wien, Fotocredit © Philipp Pess, 2025

Thilo Jenssen – Re-Formations (Milleniumcity), Fotocredit © Philipp Pess, 2025

Tamara Goehringer – DON JOY (or how to learn to walk to love), Fotocredit © Philipp Pess, 2025

Tamara Goehringer – DON JOY (or how to learn to walk to love), Fotocredit © Philipp Pess, 2025

Thilo Jenssen, Installationsansicht WAF Wien, Fotocredit © Philipp Pess, 2025

Thilo Jenssen – Reenactments IV + Reenactments V, Fotocredit © Philipp Pess, 2025

Thilo Jenssen, Installationsansicht WAF Wien, Fotocredit © Philipp Pess, 2025

Thilo Jenssen – Re-Formations (Westbnhf), Fotocredit © Philipp Pess, 2025

Tamara Goehringer & Thilo Jenssen, Installationsansicht WAF Wien, Fotocredit © Philipp Pess, 2025

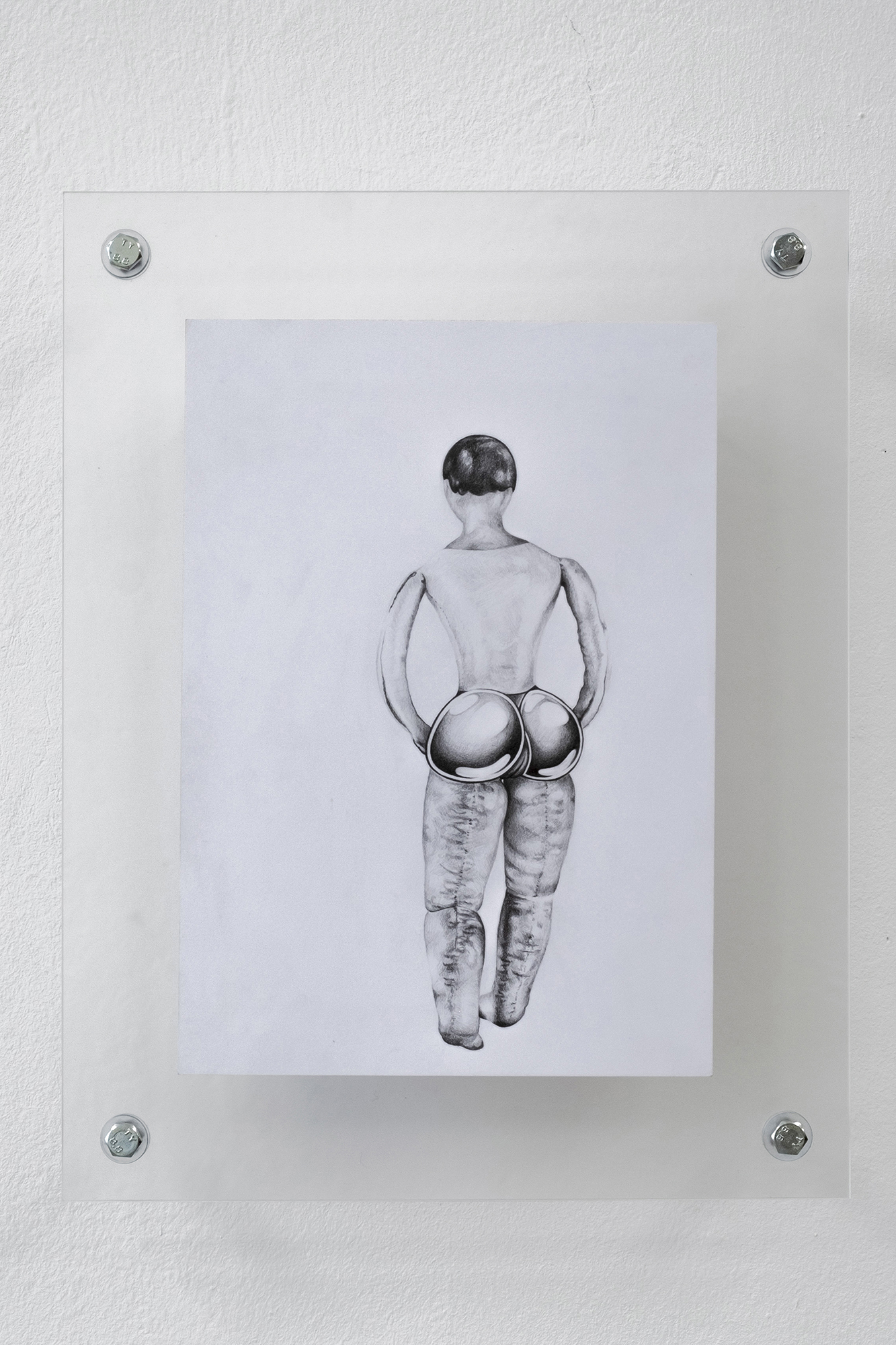

Tamara Goehringer – let's play 03, Fotocredit © Tamara Goehringer, 2025

Tamara Goehringer – let's play 04, Fotocredit © Tamara Goehringer, 2025

“It hurts. Ouch. Itai.”

A wisping voice speaks of pain. A pain that runs deep in the trunks and branches in Daniel Stubenvoll‘s film Hands and Feet on the Street (2025). The trees are held up by makeshift constructions, supports and strings. They stand in Hiroshima – not far from the epicentre where the atomic bomb dropped in 1945. Called “A-bombed trees”, their injured bodies are still present, a daily reminder of the catastrophe. And yet: they have survived. Vitality and death are intertwined in them. Even though some of the trunks have died, green crowns are sprouting. A sign of strength that may grow out of trauma and that tells of resilience amid the city, without the scars becoming invisible. Here, an active will to shape and claim public space comes to the surface, as well as moments of solidarity and mutual connection, that are too often obscured by the narrative of individual autonomy. In a more abstract way, holding together is also the theme of Stubenvoll‘s large-format monochrome paintings In ruins (2025) showing architectural elements. The wall colour used doesn’t just create self-serving strokes but is also an adhesive that attaches forms from jute canvas or plastic mesh to the image carrier.

A support structure is also inherent in the compositional elements of Thilo Jenssen‘s painting bodies Reformations (2025). These works bear witness to the injury that was necessary to cut the metal into pieces. And to the painstaking work it took to varnish and weld it back together again. With the seams, the darkening of the material through the heat, the peeling of the paint due to the piercing of the surface, the process of creation remains clearly visible in the finished works. Acting like painterly traces, these settlements encircle various bright colour fields which, for all their fragility, also seem joyful. The questions remain: Is the provisional patching up an act of care? And does fixing always go hand in hand with forcing something into a certain mould? After all, the material is stubborn, full of tension, it bends out of its intended shape instead of lying flat in it. Jenssen‘s found-footage photographs of bandages and support structures entitled Reenactments (2025) are, too, carried by a deep ambivalence. They are intended to protect, immobilise and allow bruised or broken bones to grow back together. The colourful T-shirts of those affected correspond with the surfaces of the metal paintings, as does the desire to return from being broken to a seeming whole. Despite the apparent seriousness of the situations, the bizarre constructions, which resemble props or their own characters, have something slapstick-like about them.

Pleasure and pain also go hand in hand in Tamara Goehringer‘s symmetrical textile work DON JOY (or how to learn to walk to love) (2025). This consists of a surgical splint, support straps and other medical material and is stretched like an animal skin in a metal frame. On the one hand, the piece appears like the abstract silhouette of a Rochart test fanning out around a vulva-like centre, on the other hand the corset-like form testifies to discipline and control. Stretched to bursting point, the textile seems confined and yet close to breaking free. The fact that the medical material also has something erotic and fetishistic about it reveals a hybridity that is also inherent in the artist‘s drawings entitled let‘s play (01–04) (2024). Here, Goehringer combines European depictions of dolls from the 18th and 19th centuries with elements from Japanese hentai comics. Big saucer eyes stare at us, plump breasts push out of a tied top, a round bottom is thrust out at the viewer. The stylised, almost alien-like bodies look sculptural, oscillating between object and human in an unsettling way. In fact, “hentai” means “metamorphosis” or “transformation”, in a sexual context “perversion” or “abnormality”.

In a system in which functioning is the top priority, the deviation from what is considered “healthy” and “normal”, the vulnerability of our bodies, is a political issue. It is closely linked to social exclusion processes, power relations and questions of participation. At the same time, it is precisely this vulnerability that harbours the potential to enable empathy, liveliness and community. In the second part of Stubenvoll‘s film, the first-person narrator tells the story of how the game of pétanque was born out of injury: where boules thrive on strength and heroic gestures, one player‘s body could no longer keep up due to illness. Instead of excluding him, the rules were changed. From now on, it was only possible to throw from a standing position, without a run-up. The fist gripping the ball is proudly stretched upwards. A gesture of victory? Certainly, a gesture of selfassertion – and hope.

“I‘m still standing, yeah, yeah yeah” the voice sings brightly at the end.

Ramona Heinlein