Archive

2019

KubaParis

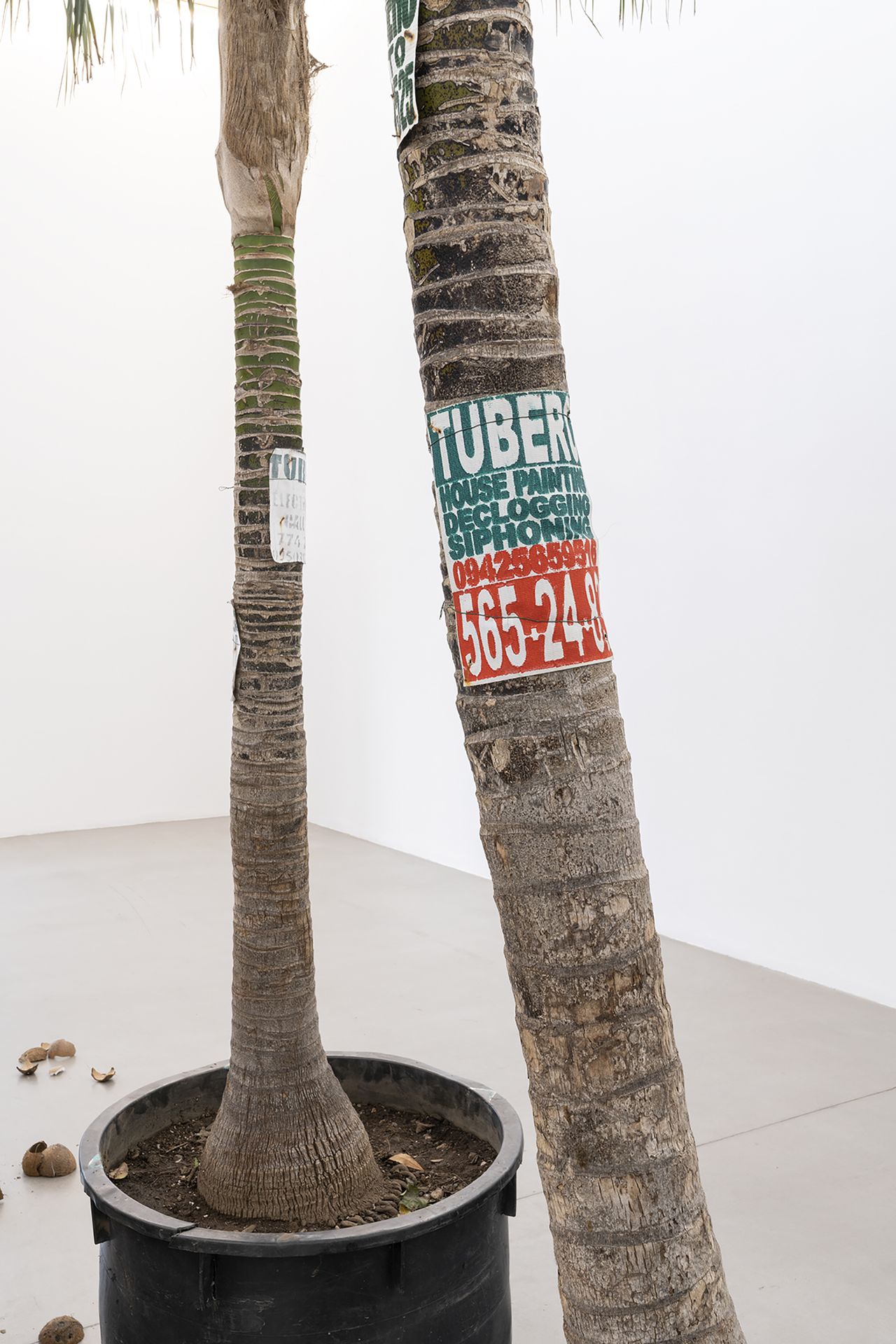

Cloudy with a Chance of Coconuts

Location

PortikusDate

18.12 –01.02.2020Photography

Wolfgang Günzel / John Torres & Shireen SenoSubheadline

On the occasion of Shireen Seno's and John Torres's exhibition Cloudy with a Chance of Coconuts at Portikus, Jasmine Grace Wenzel spoke with the artists about filmmaking as an act of befriending, leakiness and a sense of home.Text

JGW: First I would like to hear more about how you interweave your personal life with your work. A strong sense I have of your practice is that you deeply embed your way of narrating with personal events and yet rework the material in a way which leaves it open to alternative interpretations by viewers. How would you describe your forms of storytelling? Would you see it as a form of personal sense-making?

SS: Yes exactly, a form of personal sense-making, first and foremost. Making work as a way of acknowledging we are never fully formed but rather always in the process of becoming ourselves.

JT: When I first started making films, I really liked that I was gathering fragments of everyday and striking details of a place when I was filming to gather them together on a mini-DV tape to be reviewed over and over. They felt more like an exercise of feeling, and from early on I embraced my way of zooming in and out to transport me to a fictional dialogue I could almost hear, between strangers, keeping myself at a distance, having this breathing space to be okay with things not being understood. I felt like the personal-ness of the process of filming itself was what I felt at home with, so that I was able to finally at that moment come to terms with my own ways. I still gather things up to now, I feel it is all an exercise to move and collaborate with things we didn’t plan for.

JGW: Just before I got here, I was revisiting one of your previous collective works, NANG and the edition on Scars and Death which John co-edited. It is a magazine about movies and film practice from Southeast Asia. Many of your friends in the Philippine film scene contributed with writings and visual material. To me, this issue is very much in tune with the time I spent with you in the house of Los Otros1. I remember living with you in this house in Teacher’s Village in Quezon City and how everyone, mostly your friends and colleagues in the Philippine film scene, would come by and hang out, and how it was really a place of ‘mahabagin’, the Tagalog word for compassion. Do you want to talk more about your forms of relating collectively while working as Los Otros and Tito & Tita2 and which spirit it embodies?

JT: Credits really go to Khavn De La Cruz, Roxlee, Lav Diaz, and to our love for both, music and film. I remember when we were in Singapore for a film festival, that was practically my first time to show my work to a foreign audience. What I remember most was how freely everyone related to one another, playing improvised music together on the guitar, being very open about performance, and speaking about our own lives and dreams in an empty mall early in the morning. It didn’t feel like they were filmmakers as much as they were fun-loving people who just wanted to roam and explore. This really inspired me not to take my craft too seriously, because it all seemed we were more interested in things bigger than this. This is what I wanted to kind of pass on to the rest, aspiring artists, to never lose the spirit of play and to welcome open structures along the way. I see filmmaking as an act of befriending. In NANG, I wrote that I was also massaging friends’ backs and shoulders when we used to hang out, to calm them down and also to communicate with them through touch. Some of my friends don’t often express through words, so I always trick them into saying that when I touch their shoulders, I get to know their secrets and their own ‘state of affairs.’ We developed this language as friends in order to better understand each other through sublayers, subtitles and what is left unspoken.

SS: This sense of collectivity in Manila was new and refreshing for me, and it’s really what drew me here and what continues to ground me. We've been so fortunate in having other film and art initiatives around to engage us, and in being able to travel for our work, it became quite necessary to open our personal space as well.

JGW: It seems to me that your work stems from a very intuitive and explorative approach to found footage, revisiting material traces of the past and working with them, turning them into something new but never trying to detach it from a still present past. Do you want to speak about the temporal orientation of your work and about your connection with the past? How do you explore the relationship between personal histories and the collective narration of a history of a people?

SS: I like how you put it – a still present past. I think it is really interesting how they vary between people, these histories. For my film Big Boy, I was trying to exorcise my own versions of family histories. I was realizing there is a multiplicity of ways of looking back into the past, that it is not black and white, not so solid. Until now, I think I am still trying to process what was happening while growing up. But I like that, to keep some degree of mystery there, so there’s always another layer to peel off. To share with others is very important, I think, too. In college, I was very influenced by a teacher who suggested that we think of films in terms of problems, and that asking why is not nearly as interesting as asking how. I chanced upon several works that really resonated with me because they were not the closed kind of work in a conventionally closed form or medium. They kept a degree of openness to them and made me think about my own life, my own problems and own histories.

JGW: In your previous work it seems to me that feelings of being away from home, homesickness and a certain sense of longing and belonging plays a relevant role. Can you talk about this more, also about the notion of family in the context of living and working in the Philippines while engaging internationally as cultural producers?

JT: I remember when I was around 11 or 12 years old, I was wearing campaign shirts bearing 'Marcos for President’ text, complete with badges screaming to continue on with the Dictator’s reign in the country. I never knew what Marcos stood for at that time.3 But my family, who were both born and raised in the Solid North, were loyal to him. So I wore the shirt and the button. I had just transferred to a Jesuit school that stood behind Cory Aquino, and so all of them wore all things yellow. I didn’t understand why everyone on TV were on EDSA for what would be later referred to as the People Power Revolution.4 Everyone seemed so happy to oust Marcos. And I had a feeling this was a significant time. Things slowly dawned on me as the years went by, and I felt like I missed out on something. When I was making Years When I Was A Child Outside, it was the time when I walked around the different parts of my father’s body. To massage his different aching parts, from the back to the legs. He never really talked about what happened when we learned about his many secrets, the secret children who called him Father, so I took it upon myself to take advantage of taking flight rather literally when I would take my time filming outsiders of many circles in life: relationships, politics, games, geography. I began to see myself as an outsider myself, and I longed to connect with others who thrived in making work outside circles.

SS: I grew up in Japan in this strange kind of international school environment, representing the Philippines without really feeling part of either nation. My mom was a teacher and I felt like I had to be a model student. We would travel during our summer vacations, but never really became connected to other people or places. So I was going through the motions on this so-called path to success, but not really feeling in touch with the world outside as well as inside of me, just carrying a certain emptiness and a certain pressure, the push and the pull of all these forces. I decided I needed to go far away from my family, and it wasn’t until I was alone in Canada after college that I realized I must go back to try and piece myself together.

JGW: Both of you develop your practice in very open forms. I see it in your ways of narration, in applying different lens-based practices and it also shows in ways of how you interact in collectives. Can you talk a bit more about this leakiness in-between?

SS: I like the idea of leakiness. We need each other, we need exchange. In between fluid and solid. Because so much of the time we are, at least in film, so serious about certain endeavours, solid in a way. But as soon you become more relaxed, things can start to flow.

JT: Give me more of those leaks. They save me, save me, save me. I always layer the work in a way that allows more chances for things to leak so I can be blessed by them, and so they can change the material so that it turns into something else. Most of the time, they make me look like I knew what I was always doing all along, especially when it has elevated into a symphony of coincidences. Because of the leaks, they turn into something else that I could never ever do alone.

_

[1] Los Otros is an artist-led space and a collective around film practice in the Philippines. Here, John Torres and Shireen Seno have been making and presenting work with friends and colleagues since as far back as 2003. Los Otros is located in their home-studio-garage in Quezon City, Metro Manila. More about their activities here: https://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/interviews/los-otros-shireen-seno-john-torres-interview-experimental-film-community-philippines (14.02.2020).

[2]Tito & Tita is a film and art collective from the Philippines in which John Torres and Shireen Seno are involved. Their work spans installation, film, photography and collective actions. The name Tito & Tita is Tagalog and translates into 'uncle and aunts', suggesting an informal network of artist collaborators who are centrally concerned with possibilities of photographic media and its various histories. You can find documentation of their work here: http://titoandtita.tumblr.com (14.02.2020).

[3] Ferdinand Marcos was President of the Philippines from 1965 to 1986 and ruled as dictator under martial law from 1972 to 1981. He was forced out of power by Filipino people who could no longer bear the structural plunder and human rights abuses of his regime, by the People Power Revolution in 1986.

[4] Maria Corazon Cojuangco Aquino, known as Cory Aquino, held the office of the President of the Philippines after the People Power Revolution in 1986. The People Power Revolution, also called EDSA -, or Yellow Revolution, was a series of public civil resistance against the Marcos regime, mostly in Metro Manila. The non-violent protests ousted the 20-year rule of Ferdinand Marcos after the opposition leader Ninoy Aquino was assassinated in 1983. His death led to a number of events which were followed by the PPR. The name Yellow Revolution stems from the yellow ribbons, a symbol of Marcos' opposition, which eventually became associated with the Aquino family, and by extension, the liberal party.

_

Shireen Seno is a lens-based artist, filmmaker and curator, known for her movies Big Boy (2012), Shotgun Tuding (2014, short), and Nervous Translation (2018).

John Torres is a director, musician and producer, known for Todo todo teros (2006), Taon noong ako'y anak sa labas (When I was a Child Outside, 2008), Lukas nino (2013), and recently for his last movie We Still Have to Close Our Eyes (2019).

Together, both artists are part of the collective Tito & Tita, exploring more conceptual and performative dimensions of moving images. With Los Otros they produce and present film and video work, in the form of both screening programs and exhibitions.

Jasmine Grace Wenzel is a writer and editor of GROVE Journal, an online/print magazine for creative ecologies. She is based in Berlin.

Jasmine Grace Wenzel