Roman Ondak

Wish We Were Here

Exhibition view, Roman Ondak: Wish We Were Here, Galerie Martin Janda, Vienna, 2024

Advertisement

Exhibition view, Roman Ondak: Wish We Were Here, Galerie Martin Janda, Vienna, 2024

Exhibition view, Roman Ondak: Wish We Were Here, Galerie Martin Janda, Vienna, 2024

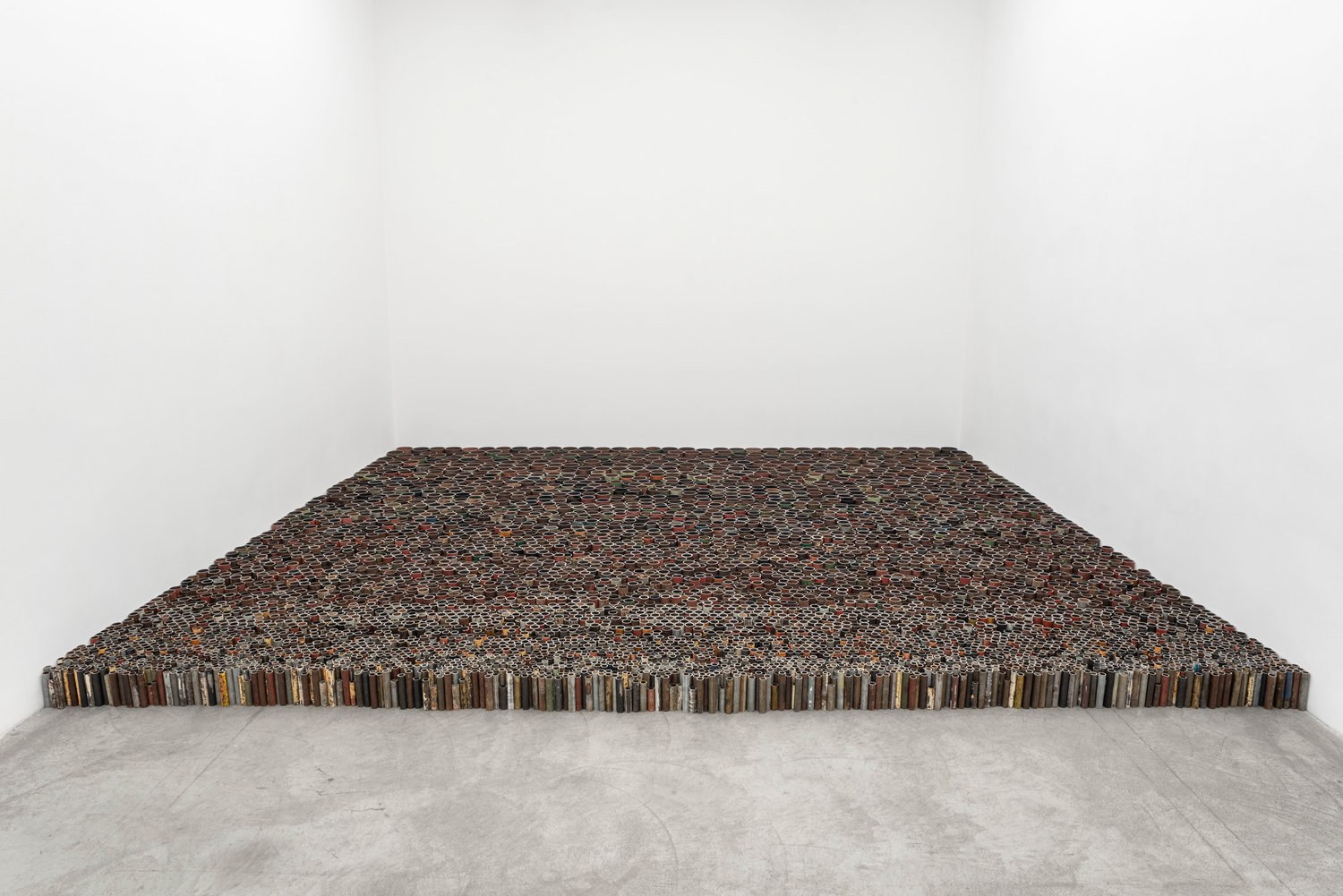

Roman Ondak, Dystopia, 2021, modified heating, water and gas steel pipes, overall dimensions vary with the size of the room

Galerie Martin Janda is pleased to present Roman Ondak's fifth solo exhibition, Wish We Were Here, from 12th April until 1st June 2024.

It seems only right that postcards are a recurring conceit within Roman Ondak’s practice. For almost three decades, the artist has carried on a stubborn correspondence with the history of art, interweaving references to the contemporary canon within his own investigation into the porous borders of reality and representation. But his is a practice that willfully confuses here’s and there’s, conflating sites with souvenirs to produce objects-as-experiences and experiences-as-objects.

There’s a wily humor to his manipulations and provocations, which derive obvious pleasure in their gentle violation of “natural” orders. Take It Will All Turn Out Right in the End, 2005–06, an installation that reproduces the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall at one-tenth of its size, reversing the dynamic of its staggering scale so that it is now the viewer who looms large. Or Failed Fall, 2008, an installation that revels in the visual punchline of dried autumn leaves scattered around an indoor garden of verdant palms (a gesture that finds more morbid echoes in the tattered parachutes dangling from trees, cliffsides, or even Brazil’s famous Christ the Redeemer in the found photo series Fail to Fall, 2010).

These disruptions can be subtler, as well. The Stray Man, 2006, unleashed a would-be spectator at a remove just legible enough to produce a vague discomfort within the exhibition space, while the sly SK Parking, 2001, stationed seven sedans—all made by the formerly Czechoslovakian brand Škoda, all bearing Slovakian license plates—in the clearing behind Vienna’s hallowed Secession. Other documentation shows the cars—not quite squatters, not quite guests—casually colonizing a parking garage, suggesting just enough of a coincidence to be implausible, but not impossible. For Good Feelings in Good Times, 2003, Ondak orchestrated a similar uncertainty—an immaterial question mark, to borrow the formal vocabulary of one of his influences, Július Koller—by planting patient queues of people who appear to wait for no particular reason. Again, not squatters, not guests: there for a purpose, though perhaps one inscrutable to the audience.

Following this kind of logic, Ondak has developed a substantial body of work that reroutes everyday objects and experiences. Unlike in the refined discourse around readymades, which would see these humble objects “elevated to the status of art,” Ondak’s found objects refuse to go willingly. They cling to the traces of their former utility with an awkwardness that scratches at our ability to perceive them within the exhibition context. Just as with the lines to nowhere and for nothing, we have to reckon with these objects as they are, irritants bearing both aesthetic aspirations and the tiny tragicomic friction of the functionless.

Ondak’s interventions affix found doorknobs, bolts, switches, and window handles to immobile walls, so that the elements can only pantomime their intended function. His sculptural arrangements of keys capitalize on the aesthetic properties of the objects, while still conjuring the hundreds of unattended locks left in their wake. Meanwhile, his sculptures with keyholes play out a minidrama in which the accessibility promised by the fixture is available only through the limited contours of the recess for the key itself, a miniature window into a space with no “there” to wish one was.

If language is what props up the conceit of the readymade, Ondak uses his titles to tease narratives (and the denial thereof) for his objects and interventions, toying with the audience’s expectations through deftly-deployed turns of phrase. The artist evoked an entire unwritten narrative by titling a charred fire alarm box After, 2017, while, like a magician, Captured Void, 2012, converts a vacuum bag and wicker basket into a domesticated black hole. Door Left Ajar, 2014, applies only the bottom edge of a door to trace the outline of where it would be in relation to its frame had it been left slightly askew, creating an impression of an opening where there is no closing. Bed (Northwest and Northeast), 2024, arranges sections of various corners of a wooden bedframe into a wall-mounted sculpture, the intentional mismatch of “frames” drawing attention to the void where an image might otherwise go. Another new wall piece, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, 2024, reassembles three small drawers into an uneasy triangle of interlocking edges, rendering the objects as ornamental as the “national” values they derive their name from.

In 2018, Ondak salvaged a series of copper pipes used for gas, water, and heating from a building in Bratislava. Sawing them to only slightly differentiated lengths, he positioned them into a sunflower-like mandala on the floor. Each pipe is not flush up against the others, but rather creates the illusion of fullness through harmonious hive-like patterns that cordon the largest pipes in the center, with the slimmest forming a tight rim at the perimeter. The title—Perfect Society—lends a slightly bittersweet interpretation to the scrappy pipes left in mild disarray around the edges of the circle. When viewed from above, they suggest flower petals or rays of sunlight. From other vantage points, however, the pipes read as the unruly outcasts, the parts rejected for their chunky connections or wiry curves.

In 2021, the artist would revisit this material with Dystopia, an installation that filled the gallery wall-to-wall with martial ranks of short lengths of metal pipes, all standing upright and at attention. The pieces are not uniform; they vary in color and diameter, with the thickest set at the back, and the thinnest up in the front to create a kind of perspectival play. Some are taller, their tips poking up above the wavering horizon of the others, while the smaller ones sit tucked into the shadows of the surrounding pipes. The title poses its own kind of provocation: what exactly is dystopic in this vision of heterogenous equality?

When Dystopia was first exhibited, it was in a show that included the work Messages, 2017, a series of old postcards with their inscriptions blacked out with paint. The gesture was simple, but effective, resonating across Ondak’s oeuvre, while also referencing those of artists like Koller. In effect, Ondak strips the object of its purpose, suspending it in a state that is equal parts liberation and grief, though a grief accented by the artist’s dark humor. When there is no “there” there, we are left to reckon with what it means to be here.

For this new revival of the work, Ondak offers viewers an opening by pairing the installation with a series of works overlaying photographs of the quarry where his father worked with silkscreens of ornate crossword puzzles excerpted from youth magazines of the late 1940s. If the photographs are not exactly postcard-ready, they do bear the intonation of industrial optimism that could be found in that early propaganda. The crosswords are highly graphic, incorporating illustrations and deliberate patterning that Ondak playfully rhymes with the technical elements from the photographs. The artist purposefully excludes the puzzle clues, so that the blanks share the same suspended state of the blacked-out postcard: illegible and yet full of possibility.

Kate Sutton