Archive

2022

KubaParis

A Monstrous Fruit

Location

BerlinDate

10.02 –25.03.2022Photography

Trevor GoodSubheadline

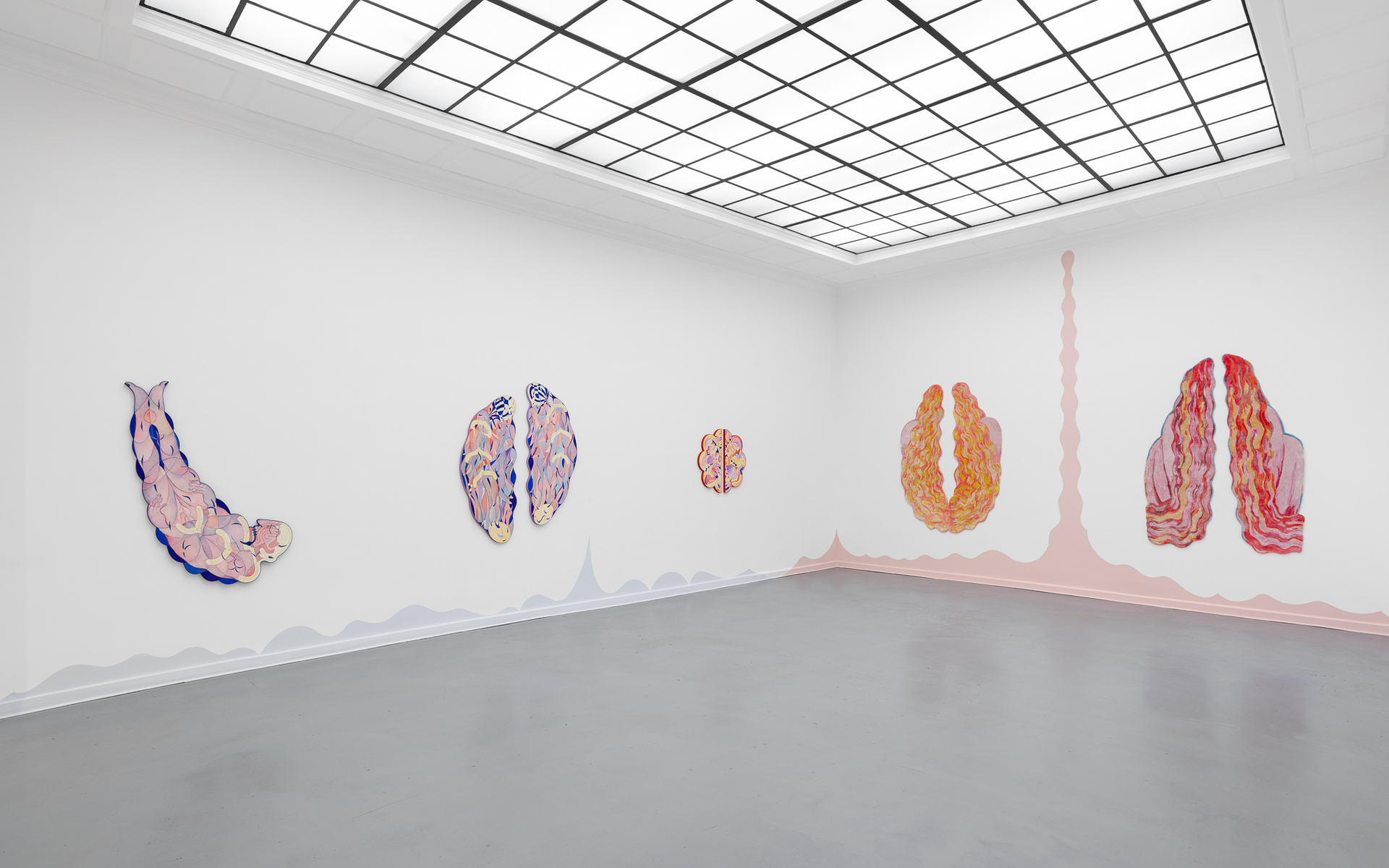

The starting point for Bea Bonafini’s exhibition of new paintings, drawings and tapestries was the labyrinth. Delving into Hermann Kern’s 1981 book on the subject during her 2020 residency at the British School at Rome, she researched this archetype, which goes back over 5000 years. The title of Bonafini’s 2022 exhibition, A Monstrous Fruit, derives from a line by Euripides, who describes the Minotaur as “a hybrid form, a monstrous fruit.” Bonafini likens the creature to “the way a fruit or a body rots and changes, where a succulent nutrient fruit becomes repulsive and toxic.”Text

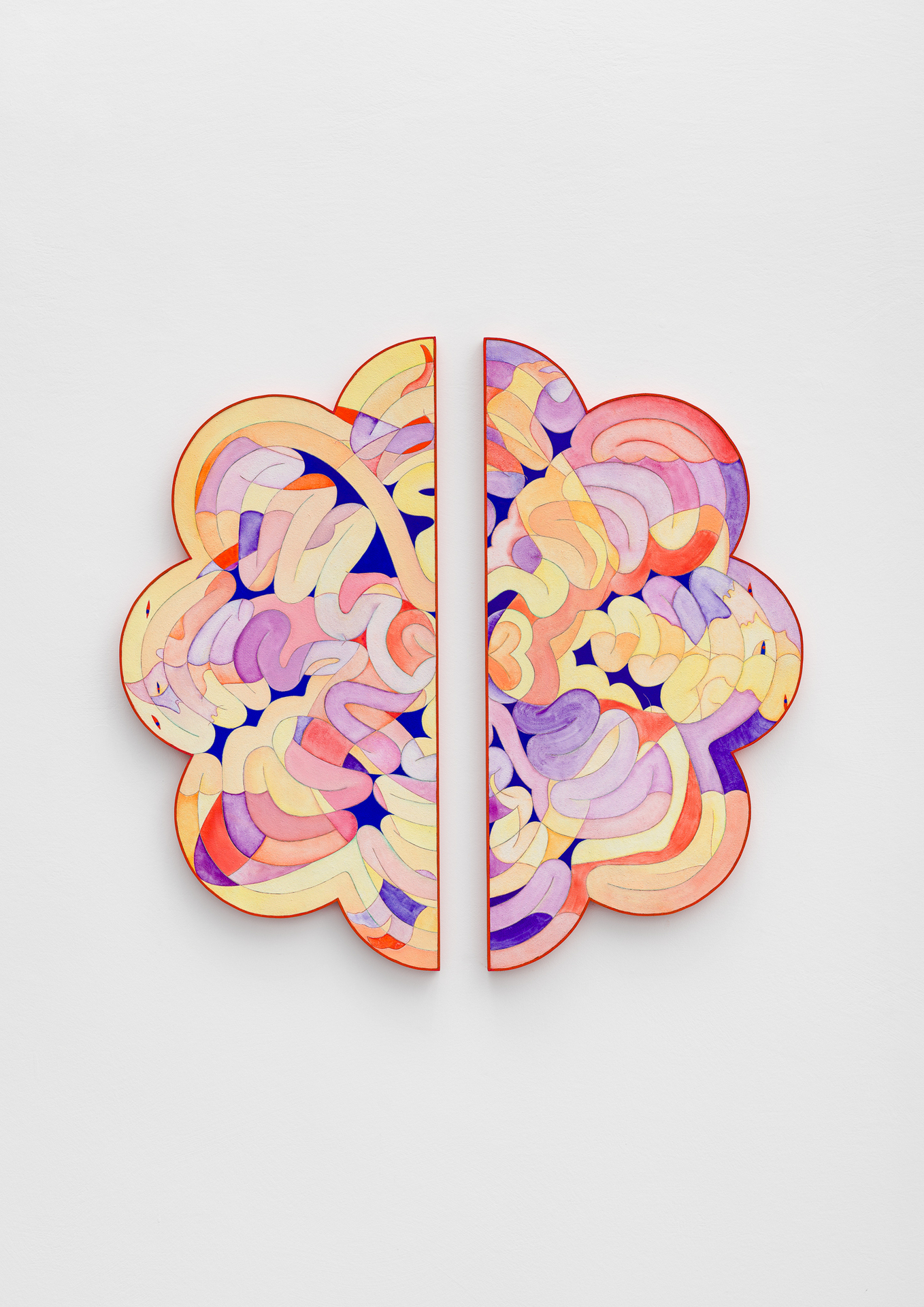

Take a sheet of cork and make two parallel incisions infinitesimally close to one another. Slice, slice. Now tease out the sliver in-between, leaving a line that is a vein by its very nature, feeding life to fragments, as well as a boundary between parts. Keep cutting until you have so many lines that shapes form within shapes. Your eye will see different potentialities in the complex patterns, maze-like, forms revealing themselves and getting lost again, in and out of focus.

The starting point for Bea Bonafini’s exhibition of new paintings, drawings and tapestries was the labyrinth. Delving into Hermann Kern’s 1981 book on the subject during her 2020 residency at the British School at Rome, she researched this archetype, which goes back over 5000 years.

Greek mythology tells the story of King Minos, whose wife, queen Pasipha , gives birth to the Minotaur, a hybrid creature, half-human, half-bull, conceived through her insatiable lust for a white bull. King Minos subsequently builds a vast and unknowable labyrinth to banish the Minotaur ‘monster’, with blind alleys and winding passages that makes escape impossible. Having never known love, kindness or touch (surely?), the Minotaur’s fate is to be slain by Theseus, who gradually unspools his lover Ariadne’s thread to successfully navigate the labyrinth.

Labyrinths have countless guises, if you consider them literally and metaphorically: tantric labyrinths used for meditation practices, people travelling through imagined passages; the labyrinth-like journeys we take before the rites of passage from childhood into adulthood (and beyond); the astrological labyrinths that historically determined the course of the sun and the planets.

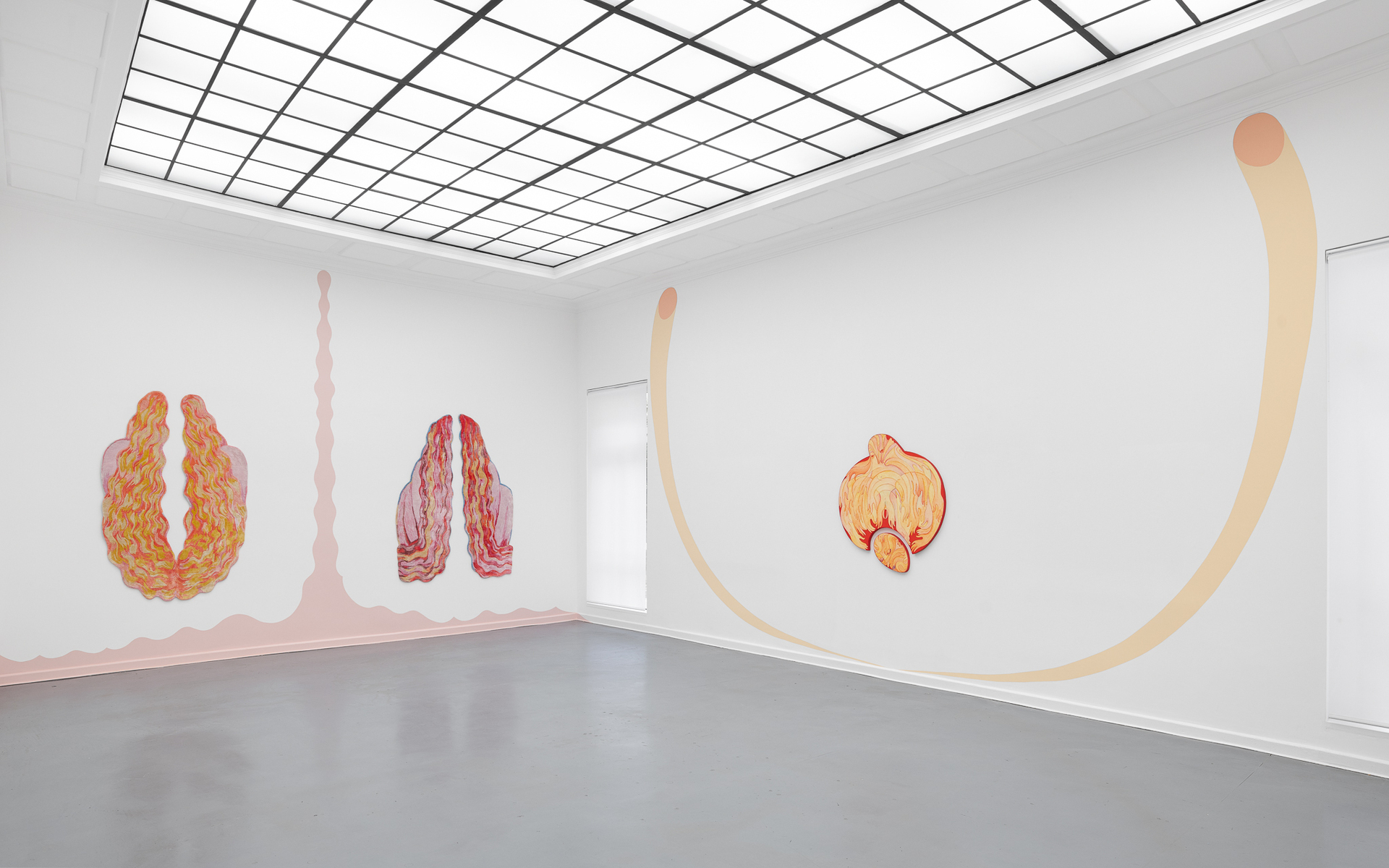

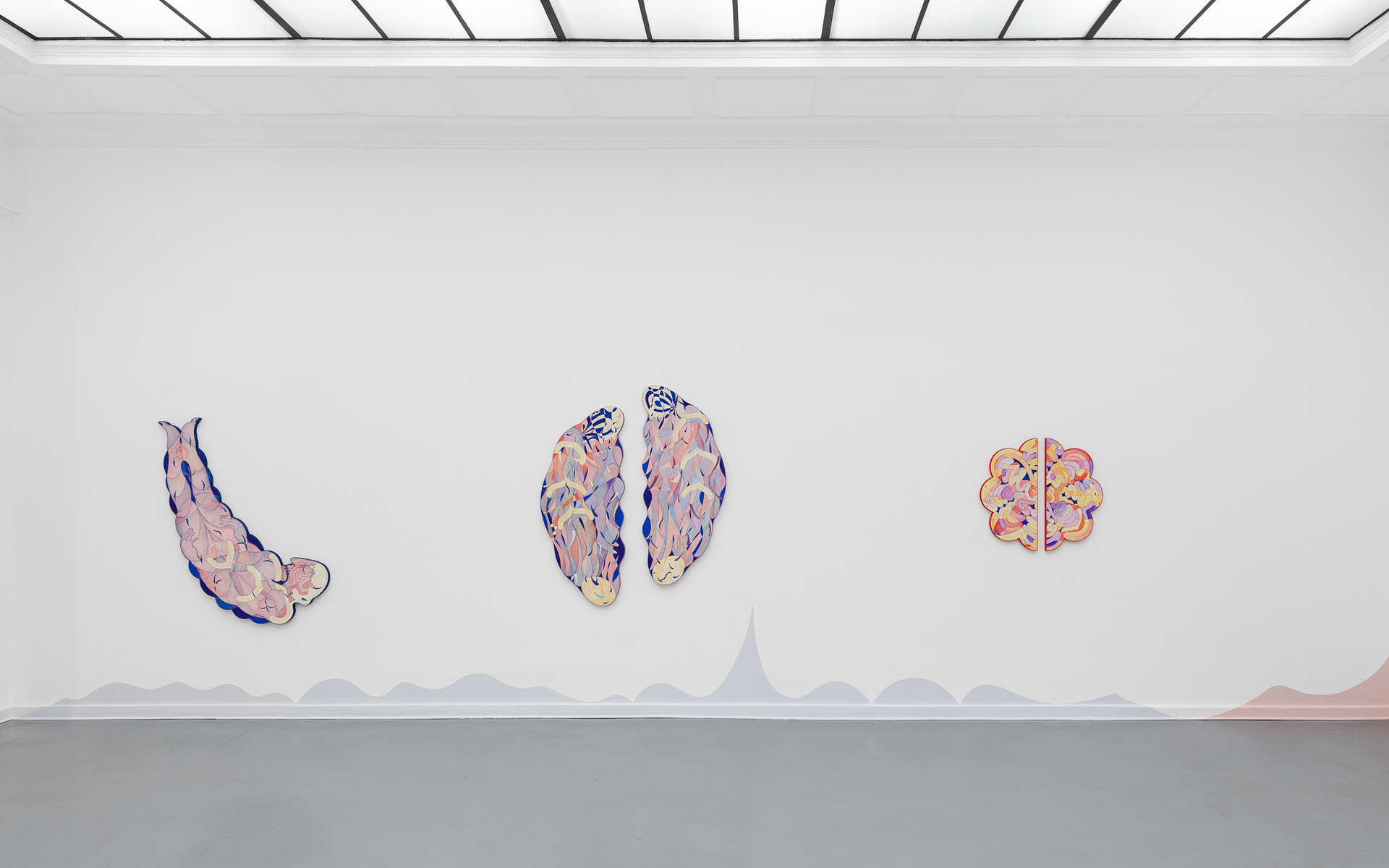

In Bonafini’s Earth’s Bowels (2022), a single-path labyrinth also doubles as an intestine or a brain, delicate fleshy tissue gently curving, ever winding and coiling upon itself. Painted with liquid washes of gouache and watercolour pencils, jewel-like colours reminiscent of Hilma af Klint – deep purples and blues rubbing up against pastels of yellow, pink and peach – swim as myriad subdivisions. Camouflaged within this softness are two bodies separated across two panels. A flexed foot, the sweep of a thigh, a face in profile. These people are at once isolated within the labyrinth whilst also being the labyrinth, imprisoned by the very lines that too express their existence. A space of confined interiority is suggested; thought patters impeding our bodies, trapped in a stream of overthinking.

My fruit bowl is piled high with skinless lemons. A spongy white pith remains as a layer of protective tissue, bearing the traces of the sharp blade inserted beneath the peel. Zingy autopsy. When left for a few days, lemons quickly dry, pale yellow pores hardening into a cratered landscape. Days later, they are solid little browning balls on the edge of decomposition. A rancid demise. A monstrous fruit.

The title of Bonafini’s 2022 exhibition, A Monstrous Fruit, derives from a line by Euripides, who describes the Minotaur as “a hybrid form, a monstrous fruit” Bonafini likens the creature to “the way a fruit or a body rots and changes, where a succulent nutrient fruit becomes repulsive and toxic.”The World’s Night (2022) speaks to a body suspended and in a state of transition. Embalmed or cocooned, within him a labyrinth unfurls from head to toe, interspersed by shrivelling hands and huge pliable wishbones. Human, animal, indefinable organism: its blue flecks look like scattered petals or, more grotesquely, small larvae breaking down the body. Back to the earth, back to the sea, up to the heavens. A return. Ritual processes with notions of the sensual and visceral underpin Bonafini’s approach to making. This body suggests the unavoidable course of changing matter, shifting shape while bound to the process of time. The rites of passage into another unknowable phase.

The sun rose as we washed you. Gently lifting your limbs, tracing the cloth across your still-freckled skin. Outside, sun. Crystal clear winter sky: a blue speaking for the heavens, the sea and the in-between. It was crisp and clear and simple. We moved in full definition, though slowly. You were still the colour of you, still the smell of you, still the stillness of you. Barely eating, I pierced the membrane of a bright orange egg yolk. Bleeding. Wilted finger, prodding. Still searching.

In the same way that an artist like Joan Miró had an ardent desire to reveal the marvellous in the quotidian – some of Bonafini’s schematic lines and opaque shapes with monochromatic grounds remind me of his lexicon – Bonafini too winks at the surreal; cascading hair mutating into lava, twisted braids into lobster claws, fingers into fish skeletons. Her paintings speak to the hybridity or manifoldness present in an unconscious mind, that reservoir of memories and emotions. Fishing Skeletons (2021), for example, depicts two interconnected beings kissing beneath a moon that merges into bone into nerves into sea into foot into hand into land into belly into claw into hair into fingernail into breast into cheek into mouth. On-going metamorphosis, or is this a genetic chimerism: a single organism composed of more than one thing? It has the sense not only of duality but shared existence, of changing cycles, time returning and repeating: of restoration.

During a period of personal grieving, Bonafini became interested in the vagus nerve (vagus meaning “wandering” in Latin), the longest of the nervous system, which is comprised of two strands: another duality. Its mass of sensory fibres spreads from our jaw down over our organs until reaching the groin. Perhaps best described as the nerve of our emotions, it regulates our mental health and wellbeing. Describing its affinity with the labyrinth, Bonafini emphasises how mourning while ritualistically bringing bodies into being played a role in her own healing:

While processing grief and working on these horizontal surfaces laid out on my table, the first markings felt like the bodies were coming to life, the washing away of pigments felt like a ritual, the incisions felt medical, providing the satisfaction of getting closer to some sort of answers or healing.

With themes not only of duality, but of multiplicity and birthing – take the eggs and nascent forms in Purer and Purer (2022), for example – Bonafini motions for the Minotaur’s monstrous fruit to seek a way out by morphing between states, finding ever-new constellations. In Eternal Incandescent (2022), an abundance of hands shapes a circulation of vital energy, the cocooned warmth of touch evading loneliness and giving birth to new life. The sumptuousness of Bonafini’s velvety reds asks for succulence and tenderness while acknowledging the deep heat of pain. The artist seeks transformation, not as a way of escaping death, but as a panacea that shows just how little separates humans from non-humans.

When the wind blows, I feel you. All the truisms are swaying in the branches, rustling with the leaves, turning in the breeze. You settle into silence and I sit with you there. Still. Content.

Louisa Elderton