Archive

2020

KubaParis

Land der Ideen

Location

ConradiDate

16.08 –04.12.2020Text

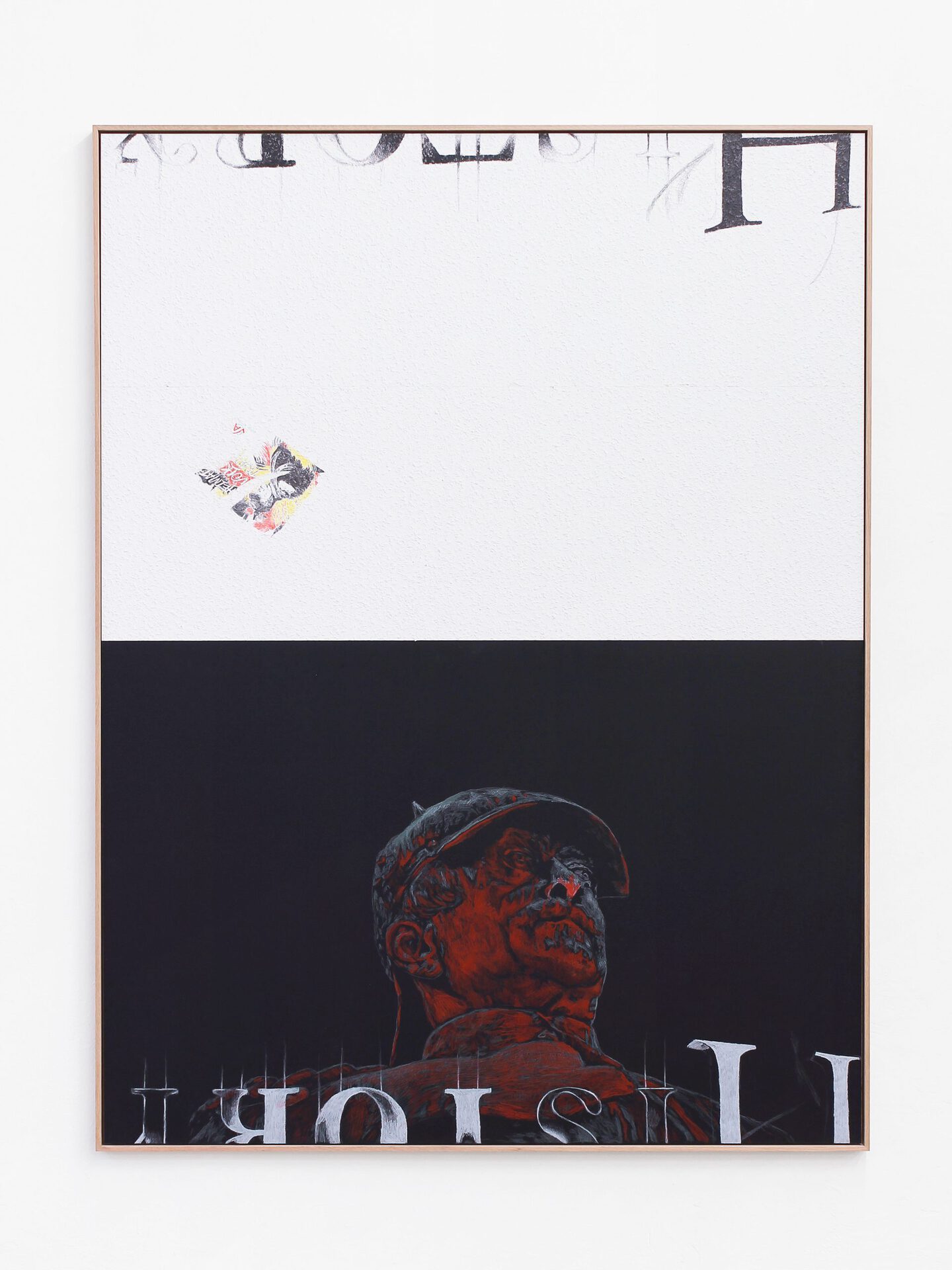

The photograph on the card with which the gallery invites the public to the exhibition Land of Ideas is a motif from Kärcher’s current image campaign. Proudly showcasing its ‘cultural sponsorship’ program on its website, the company in the southwestern German state of Baden-Württemberg boasts of its pro-bono campaign to clean the world’s largest Bismarck monument as well as other historic landmarks such as the Porta Westfalica, Mount Rushmore, or the Colossi of Memnon.

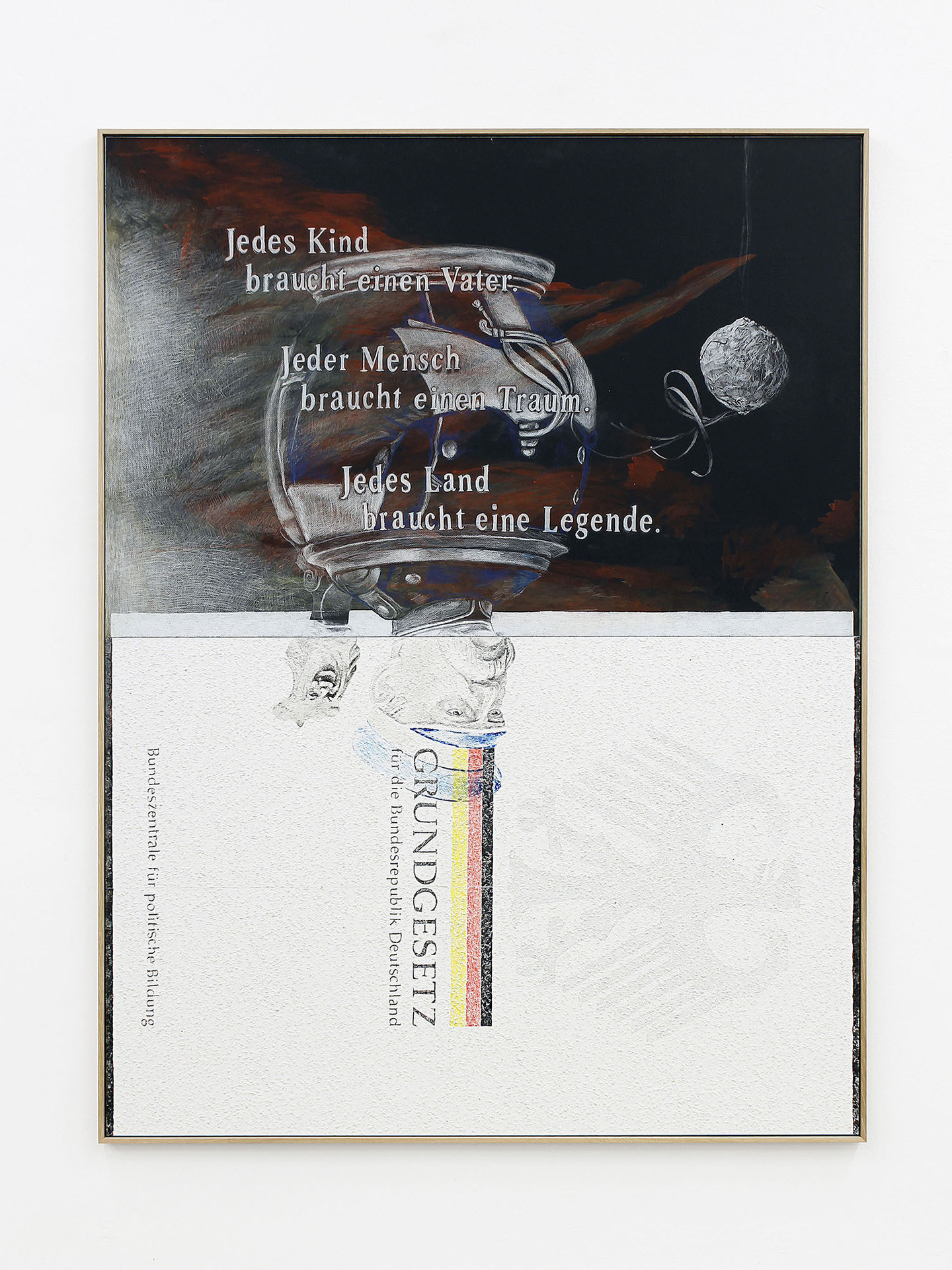

The monument, in Hamburg, features the aging chancellor of the Reich in a vaguely medieval fantasy knight’s armor, a lonely Roland supporting himself on a mighty sword. He guards the city’s Neustadt neighborhood above the piers, flanked by two eagles that nestle up to him. The influential Hamburg architect Martin Haller, a member of the jury convened in 1901 to select a design for the future monument, saw the eagles as symbolic figures, representing the prudence and vigilance of a politician whose strategic acumen was widely admired.* Heroic muscular young male nudes surround the pedestal beneath his feet. Bearing his shield and sword, they stand for the Germanic tribes, underscoring the granite monument’s nationalist connotation.

After the renovation, an expert panel will discuss what a responsible public engagement with the monument might look like today. As of this writing, no decision had been made on whether visitors would get to see the swastika murals inside the monumental structure, which was used as an air raid shelter during the Second World War. The enigmatic iconographic program of the interior decoration was unmistakably inspired by the cult of the Volk, but parts of it have yet to be decoded.

The citizens of Hamburg had ambivalent feelings about the monument from the outset. The history of what they made of it can serve as a prism on the cultural changes underlying the German public’s discourse about itself: formerly a screen for projections of grandeur fueled by nationalist sentiment, then a target of the New Right’s attempts to appropriate it, the Bismarck monument has always been a crucial pawn of diverse claims to power.

In June of this year, someone threw a red paint bomb at the smaller statue of Bismarck in Hamburg-Altona. The iconoclastic motive behind the act may be connected to Bismarck’s role as the initiator and moderator of the Congo Conference. Held in 1884–1885, the Congo Conference had sealed the partition of the African continent between the major European powers, paving the way for the ruthless pursuit of economic interests that, we now know, resulted in atrocities on a vast scale. The extent to which the exploitation of colonized countries propelled the accumulation of private wealth in Germany as elsewhere was mostly hidden behind a veil of silence for decades afterwards, as more recent historical scholarship has demonstrated.

Despite various critical debates over the past century, Germans have persisted in their reverence for Bismarck—no other personality, no poet or thinker, has had more monuments dedicated to him. Thousands of streets, squares, pharmacies, hotels, entire neighborhoods, ships, and even towns are named after him. Hitler decorated his office at the Reich Chancellery with a portrait of Bismarck by Franz von Lenbach, and the cucumbers, apples, cigars, trees, liquors, and, last but not least, the famous herrings churned out by the consumer goods industry remain perennial favorites.

The original meaning of the Hamburg Bismarck monument was forward-looking—it signaled the certain conviction that economic growth, imperial ambitions, and the cultural superiority affirmed in pathos-laden speeches heralded a great future for Germany and for Hamburg. Then, after the end of the First World War, the tone shifted.

On the one hand, the monument lost its significance as an integrative symbol and was generally seen as an apolitical city landmark. At the same time, the so-called Bismarck celebrations organized at regular intervals by nationalist fraternities increasingly attracted revisionist and national-conservative circles. Carefully orchestrated rallies stoked nostalgia for Germany’s prewar glory and idealized Bismarck’s tenure as well as the country’s colonial ventures while catering to racist resentments. These observances, some of them lavish productions, were quite popular in the 1910s and 1920s. In a society wracked by political and social tensions, their religious and even cultish quality also served to compensate for bourgeois fears of alienation. As early as 1898, representatives of Germany’s student unions had gathered at the Haus der Patriotischen Gesellschaft in Hamburg to draft a proclamation for the so-called Bismarck towers: each year, columns of fire were to rise from the braziers on these structures on April 1, Bismarck’s birthday, to suffuse the entire Reich with their heartwarming glow. Documentary records show that at one point there were 240 such Bismarck towers; 173 of them still stand, scattered across today’s Germany, France, Czech Republic, Poland, Russia, Austria, Cameroon, Tanzania, and Chile, and their popularity as tourist destinations remains undimmed.

The Bismarck commemorations reached a temporary climax in 1925. The festival—held eight years before the Nazi Party’s so-called power grab—was meant to herald a new era of German grandeur. The Bismarck Youth gathered in Hamburg and, joined by various right-wing factions carrying black-white-and-red flags and torches, marched on the monument, which was bathed in the red glare of Bengal lights. These productions paved the way for the Nazis’ visual politics, which strategically functionalized the Bismarck monuments, and especially the one in Hamburg with its adaptation of the Roland tradition, for purposes of ideological mobilization.

Björn Höcke, too, was born on April 1. The Alternative for Germany, which has adopted the first Reich Chancellor as its patron saint, has capitalized on the coincidence, staging ceremonies every year in which especially meritorious members are awarded Bismarck medals; meanwhile, the Junge Alternative, the party’s youth wing, has produced advertising stickers: a dashing Bismarck in full dress uniform grimly looking to the right before a snappy Germany graffiti and the slogan Heimat, Volk, Tradition promotes the ‘180-degree turn in the politics of memory’ that Höcke famously called for in a speech in Dresden in 2018. The so-called ‘Reichsbürger’ movement, which denies the legitimacy of the post-1945 Federal Republic and its constitution , likewise cherishes Bismarck’s memory. The scene is especially adamant in its glorification of the period between 1871 and 1914 as the golden age and cultural culmination of German history, which has led some to embrace the conspiracy theory that the Federal Republic is actually a limited liability company established by the Allies after the Second World War. These and other groups have recently begun to close ranks under the label Querfront, which has received plenty of media attention in connection with the protests against the government’s measures to contain the coronavirus pandemic.

But what has actually caused this reignited national disinhibition—how and when did cultural developments first augur what, in 2020, has led to the new alignment between organizations of the extreme right such as the Junge Alternative, the ‘Reichsbürger’ movement, Querfront, and the figure of Bismarck?

What is the Land of Ideas?

The exhibition inquires into the connections between a growing receptiveness to identity politics, which has increasingly infected the middle and upper classes as well, and the ostensibly harmless return to an identity-based national entertainment culture promoted by the media

—and finds one possible answer in the 1990s.

To discuss a linkage between political strategies of nation building like the Bismarck monument and contemporary visual cultures of nation branding, it is helpful to look to a prominent example: Guido Knopp’s History-Channel-style TV movies for the broadcaster ZDF. Knopp was one of the first to ride the wave of national rapture after the fall of the Wall and the World Championship win in 1990; he went on to work for public television, producing a number of history documentaries that leaned heavily on emotionalism to appeal to a large viewership. Titles like Hitler’s Helpers, Hitler’s Helpers II, Hitler’s Warriors, Hitler’s Children, Hitler’s Women, and Hitler’s Managers suggest an overt fascination with the creepy frisson of the Nazi era, as do the dramatic music selected for the soundtracks of these productions and the portentous narrator’s voice.

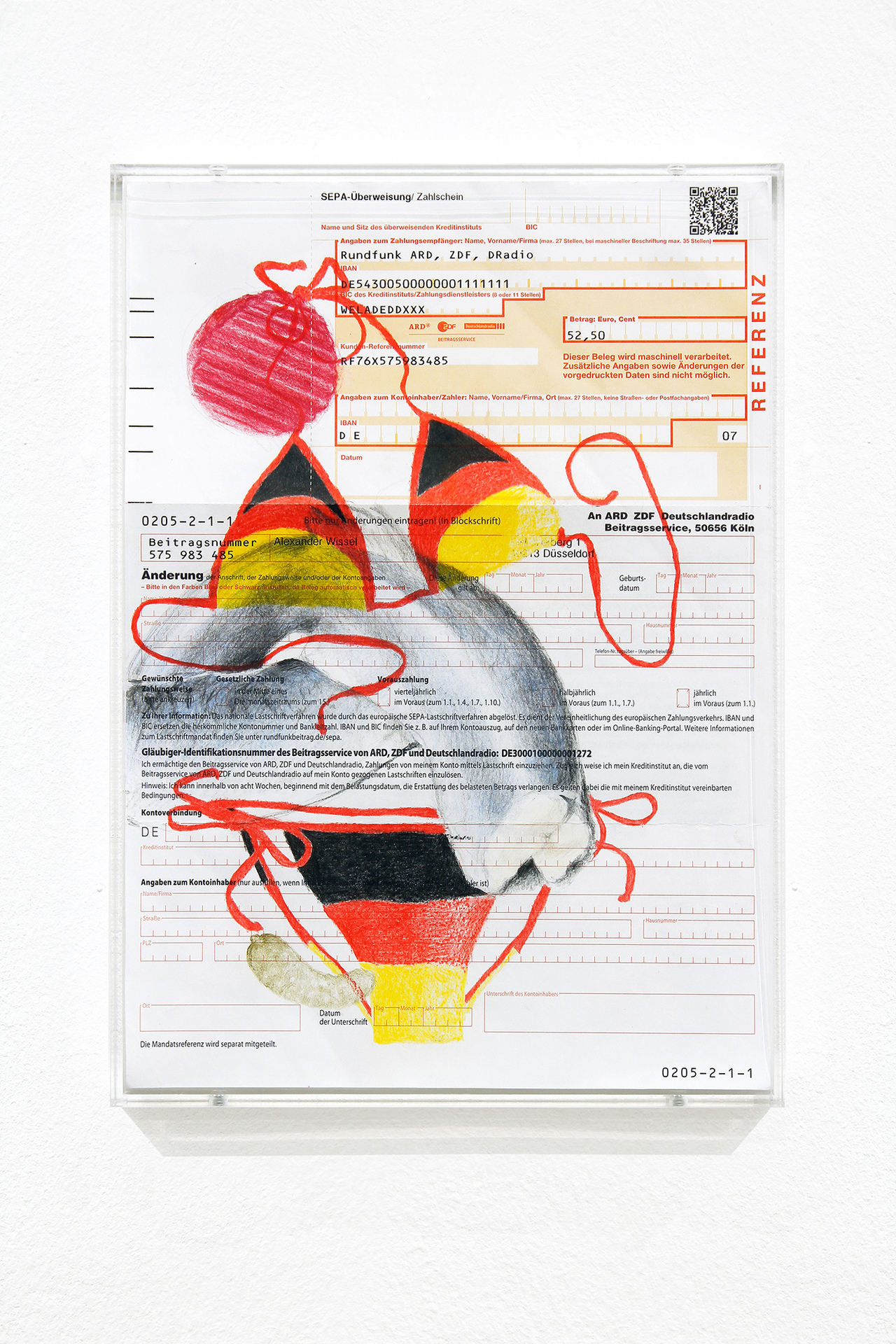

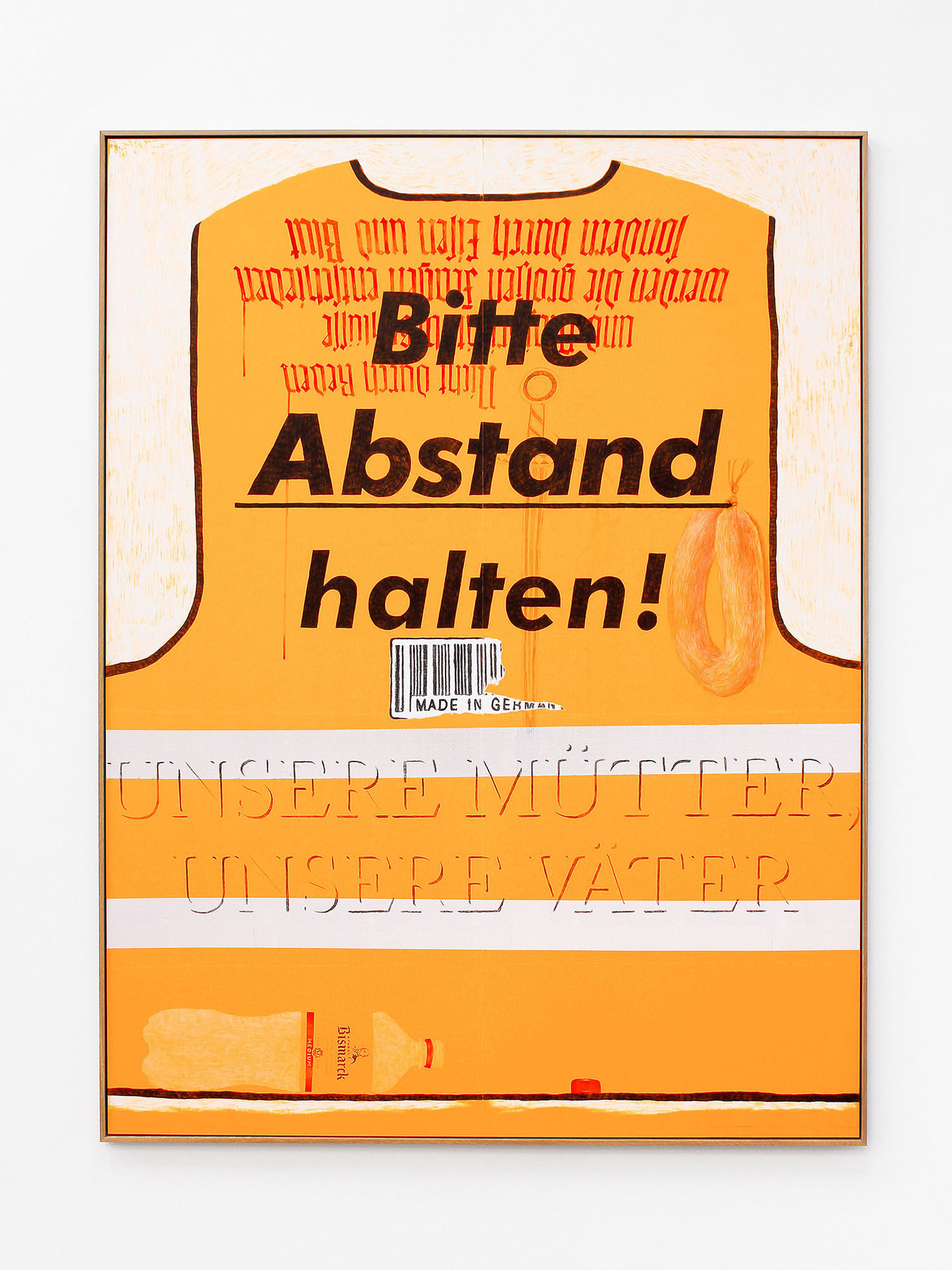

In the 2000s, Nico Hofmann, now chief executive of Ufa Productions, harnessed the same strategies of emotionalization in films like Dresden, Our Mothers, Our Fathers, and The Escape, which turned the spotlight on the suffering of the German population during the Second World War.

After Germany’s selection to host the 2006 World Championship, a social marketing campaign coordinated by Bertelsmann was rolled out that attracted controversy. Under the motto Du bist Deutschland (You Are Germany), it emphasized positive identification with Germany, fueling the rise of national sentiments in the run-up to and aftermath of the ‘home championship.’ Hamburg was home to the campaign’s strategists and masterminds as well as the ‘campaign headquarters,’ at the agencies Kempertrautmann, Jung von Matt, and FischerAppelt. Three years before the national mega-event, Sönke Wortmann had directed the movie The Miracle of Bern, a kind of how-to manual for the enthusiastically received narrative of how Germany had made peace with itself. Later, during the ‘summer of magic,’ Wortmann shot the documentary film Deutschland: Ein Sommermärchen. The Land of Ideas welcoming friends from all over the world—the major success of these campaigns and films reveals the deep desire for a national identity encapsulated in a carefree collective experience unburdened by history.

But if German flags waved by fans drunk with joy and black-red-and-gold wigs and leis figure centrally in the new storyline of German greatness, so does a rise of the New Right that was downplayed for several decades. That is why the Nationalsozialistischer Untergrund’s killing spree, the murders committed by right-wing extremists in Mölln and Solingen, and the riots and attacks in Hoyerswerda and Rostock-Lichtenhagen not only point to a structural problem, they must also be seen in the context of the swing of public opinion since the 1990s. Now, at a time of wrenching social changes, the narrative of a cosmopolitan and educated liberal middle class collides with the bewilderment of millions whose diffuse feeling that they have been left behind and that their cultural and economic status is increasingly precarious drives them to seek their self-image in legendary visions of the German grandeur of yore. As this sketch of the evolution and construction of images and narratives and the identities they have anchored from the nineteenth century to the present illustrates, the gradual rightward shift of a society’s political discourses is not the work of radicalized circles alone.

*Jörg Schilling, ‘Distanz halten’: Das Hamburger Bismarckdenkmal und die Monumentalität der Moderne (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2006)

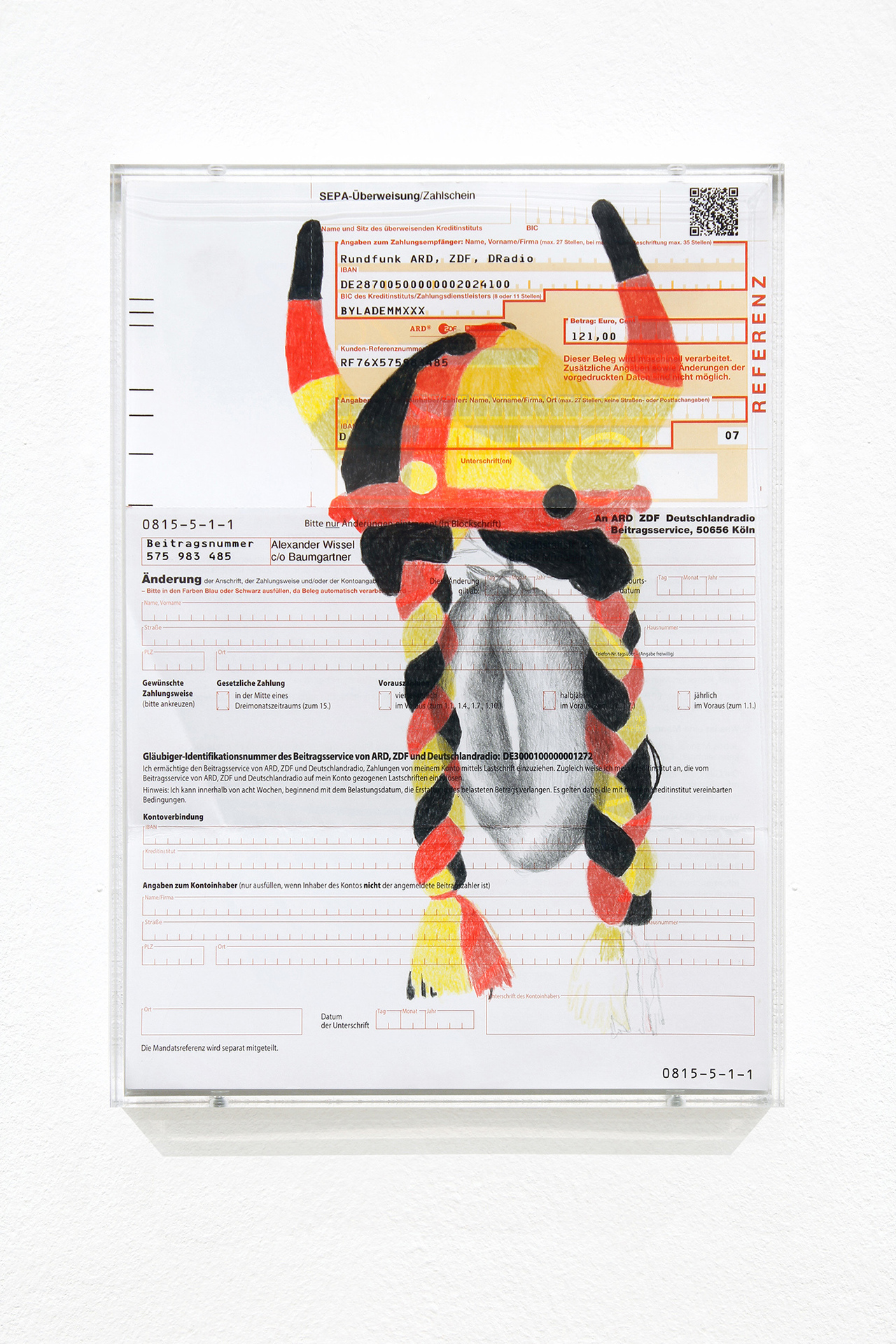

Elena Conradi and Alex Wissel