Archive

2021

KubaParis

anna-zemankova

Location

FUTURADate

06.12 –15.01.2022Curator

Lukas HofmannPhotography

Jan KolskýSubheadline

Anna Zemánková's (1908-1986) mental vegetation defies the laws of physics, and the only thing binding it to the Earth is that it indeed often grows upwards. Even though the works might evoke spiritualism in art - Hilma af Klint’s works might surface in the mind’s eye - Zemánková never spoke about any higher power at play. Being a self-taught artist, she had to devise her method - the faith in her ingenuity became one of her driving forces and a source of pride. Her dentistry practice then manifested itself in the miniature details - in almost filigree fillings and arabesques of her artworks.Text

Anna Zemánková

7.12. 2021–16.1. 2022

Curator: Lukas Hofmann

Centre for Contemporary Art FUTURA, Prague

(Photography: Jan Kolský)

More Beautiful Than Nature—The Work Of Anna:

Anna Zemánková never left us explicit instructions on how to read her work. The inspiration originated somewhere deep inside her and was more of an automated process than a rational one. As soon as her hand had drawn a shape, it informed the rest of them. The author herself claimed that she could not trace the exact source of her imagination. Nevertheless, she claimed it guided her to free herself from matter and to harmonize her soul. Even though these facts might evoke spiritualism in art - Hilma af Klint’s works might surface in the mind’s eye - Zemánková never spoke about any higher power at play. Being a self-taught artist, she had to devise her method - the faith in her ingenuity became one of her driving forces and a source of pride.

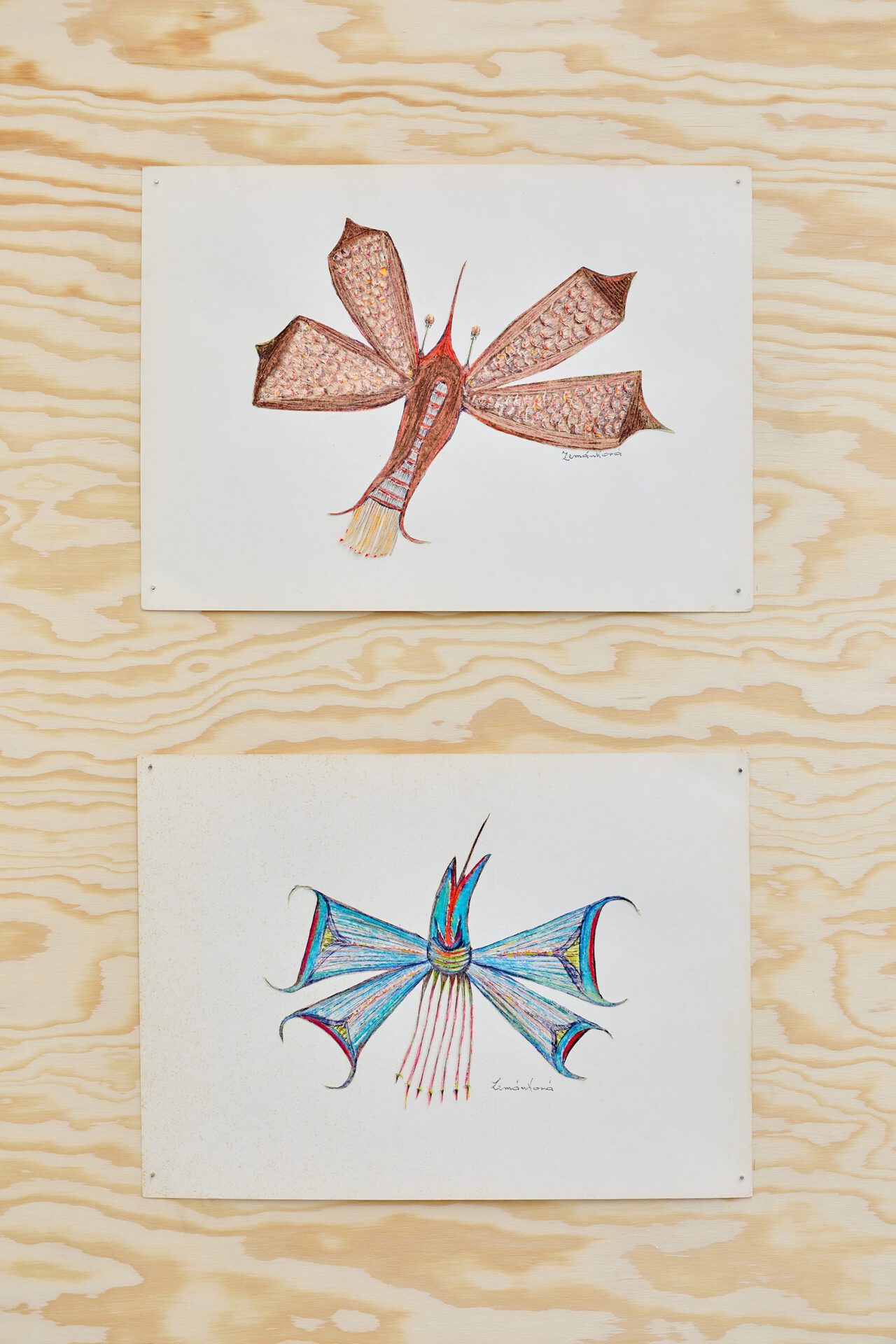

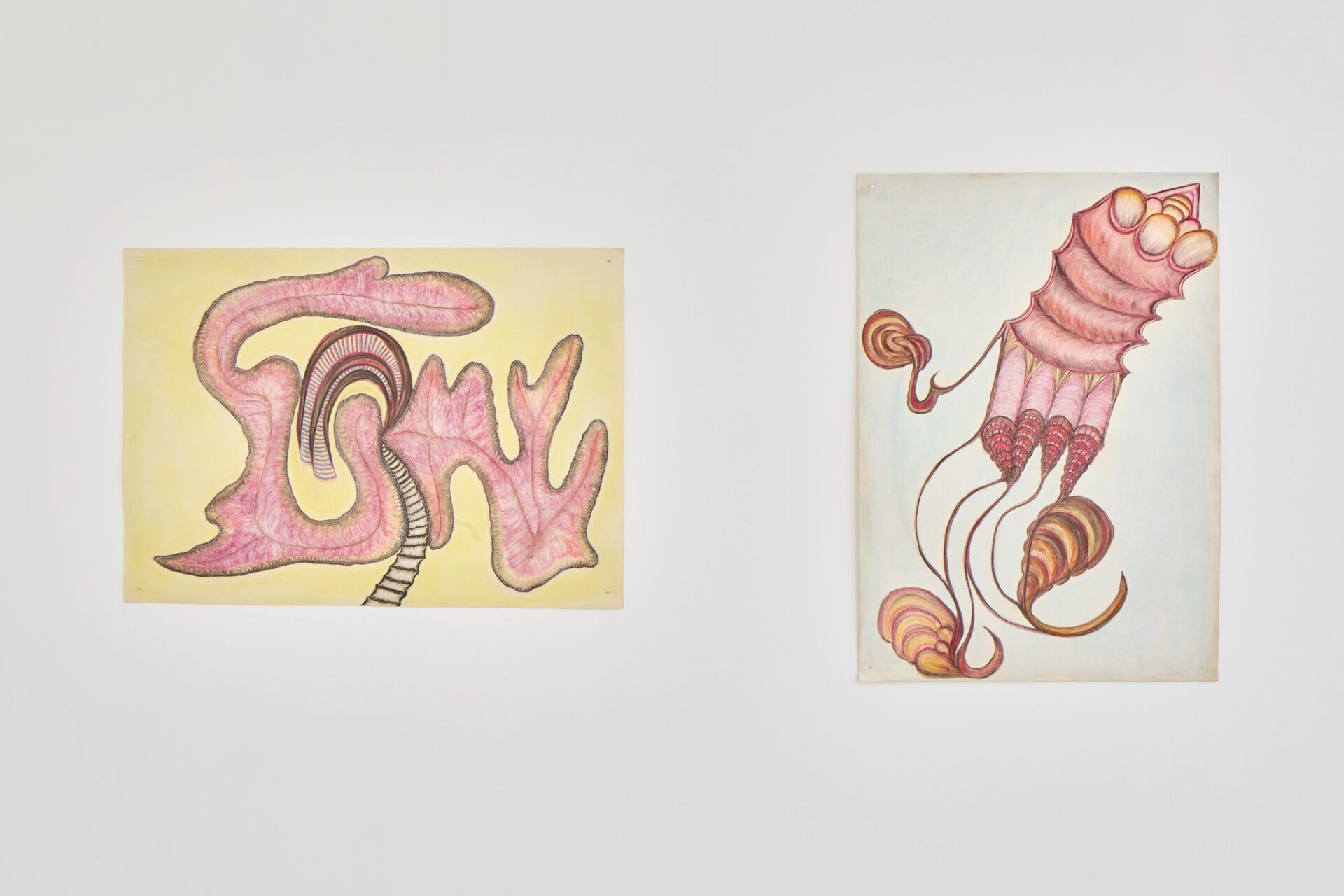

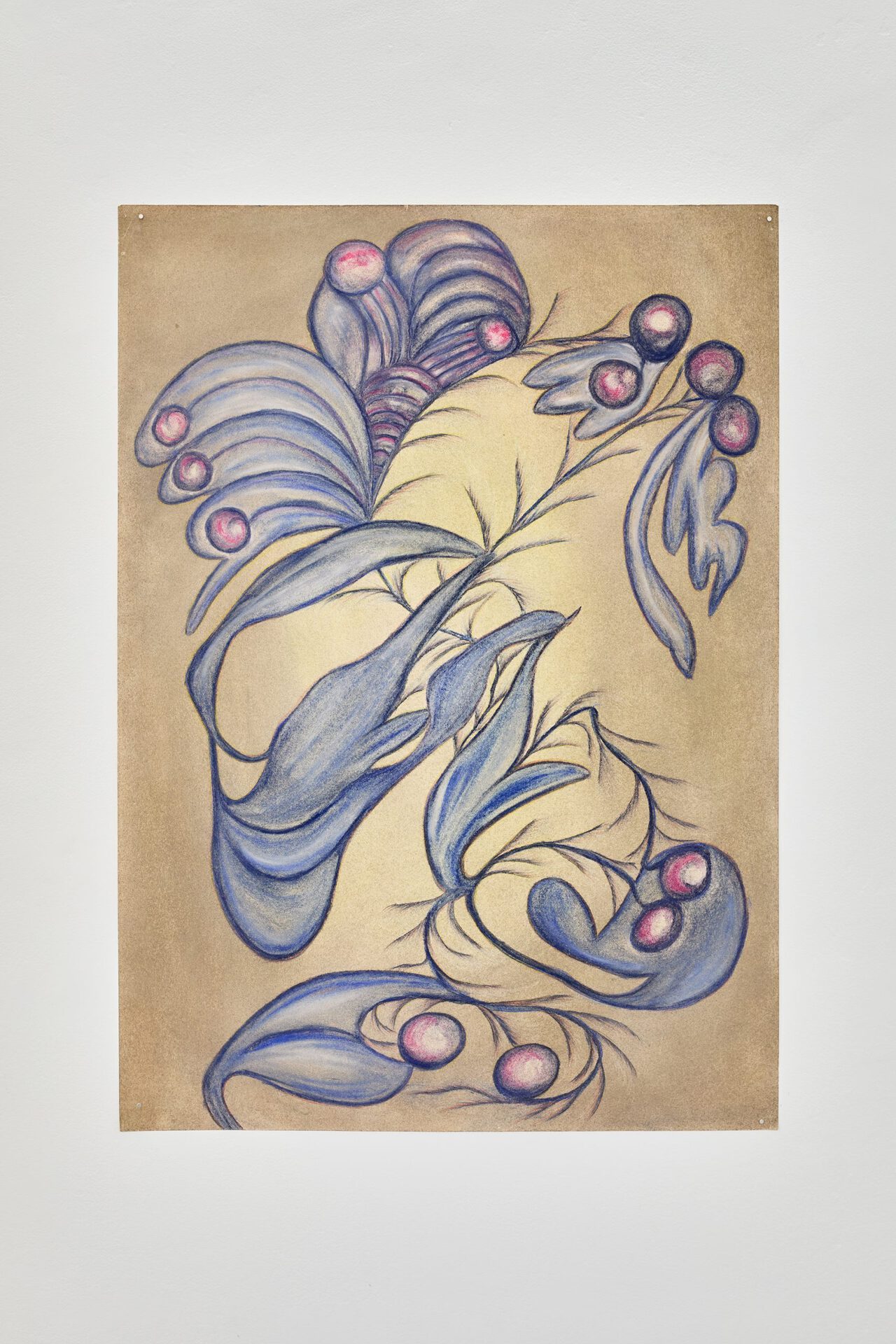

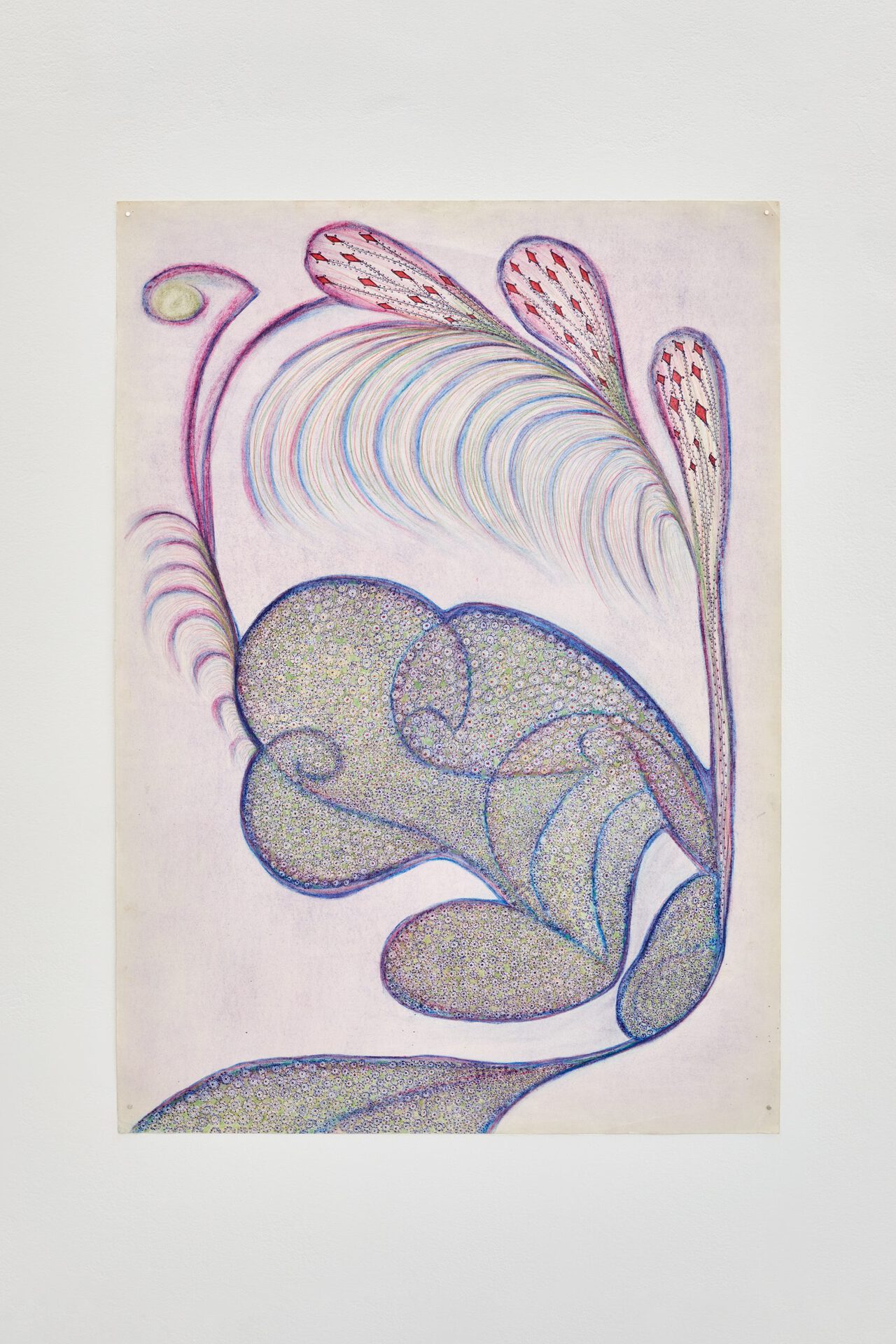

Many reasons come to mind why Zemánková stated that she exclusively created flowers. It is apparent she felt a natural affinity towards them, surrounding herself not only with fresh naturalia but also with their plastic versions. We may assume that her preference was influenced by the folk costumes of the Haná region, herbariums, and memorials, or perhaps even decorative curves of art nouveau. However, even a mere glimpse assures us that these flowers were not formed from terrestrial matter. They often vibrate with an almost ominous mystique, and in her drawings, we may occasionally observe spatial bodies and formations (allegedly, she was a firm believer in extraterrestrial civilisations). It is often unclear whether we are standing face to face with objects of orders of magnitude a few times lower or higher - whether we are witnessing tissues and division of cells, seaweed, and amorphous protozoa, or planetary explosions. This mental vegetation defies the laws of physics, and the only thing binding it to the Earth is that it indeed often grows upwards. Otherwise, it exists in the vacuum rather than in humid air.

Zemánková consistently prided herself on her themes being unique and never recurring. It is truly astonishing how many permutations one can achieve when using the idea of a plant as a material. Even though walking through the exhibition I can’t wrap my head around the multitude surrounding me, I find a specific, fertile quality precisely in this overflow emanated by her drawings, paintings, and collages, which leads to a certain out-of-body experience. Various authors dealt directly with ontological processes, libidinal desire to self-impregnate, in their interpretations of the work because the world of plants naturally provides such potential. However, Zemánková’s matter is inanimate or otherworldly, more enticing and succulent than nature itself, which makes it even sinful at times.

If we met Anna in the street or visited her, we probably wouldn’t see her as a particularly sophisticated woman - she created a “fairytale kingdom” at her home in Nusle, surrounding herself with kitschy things and a deluge of fresh as well as artificial flowers. That’s because, in her living space, she preferred conventional beauty. However, in her artistic practice, it was the other way around - she seems to be bolder and imaginative in her creative expression. Remarkably, these two aesthetic concepts split so thoroughly, giving rise to art as a sacred vessel where the author stored her creative tension and spiritual exaltedness. The same schism between the author - “an ordinary woman” - and her extraordinary work occurs in almost a superhuman focus often necessary to produce tens of thousands of dots and lines in the drawings’ details, which Zemánková always produced without errors and smudges, with the skill and rigours which would have also been necessary for her job as a dental technician.

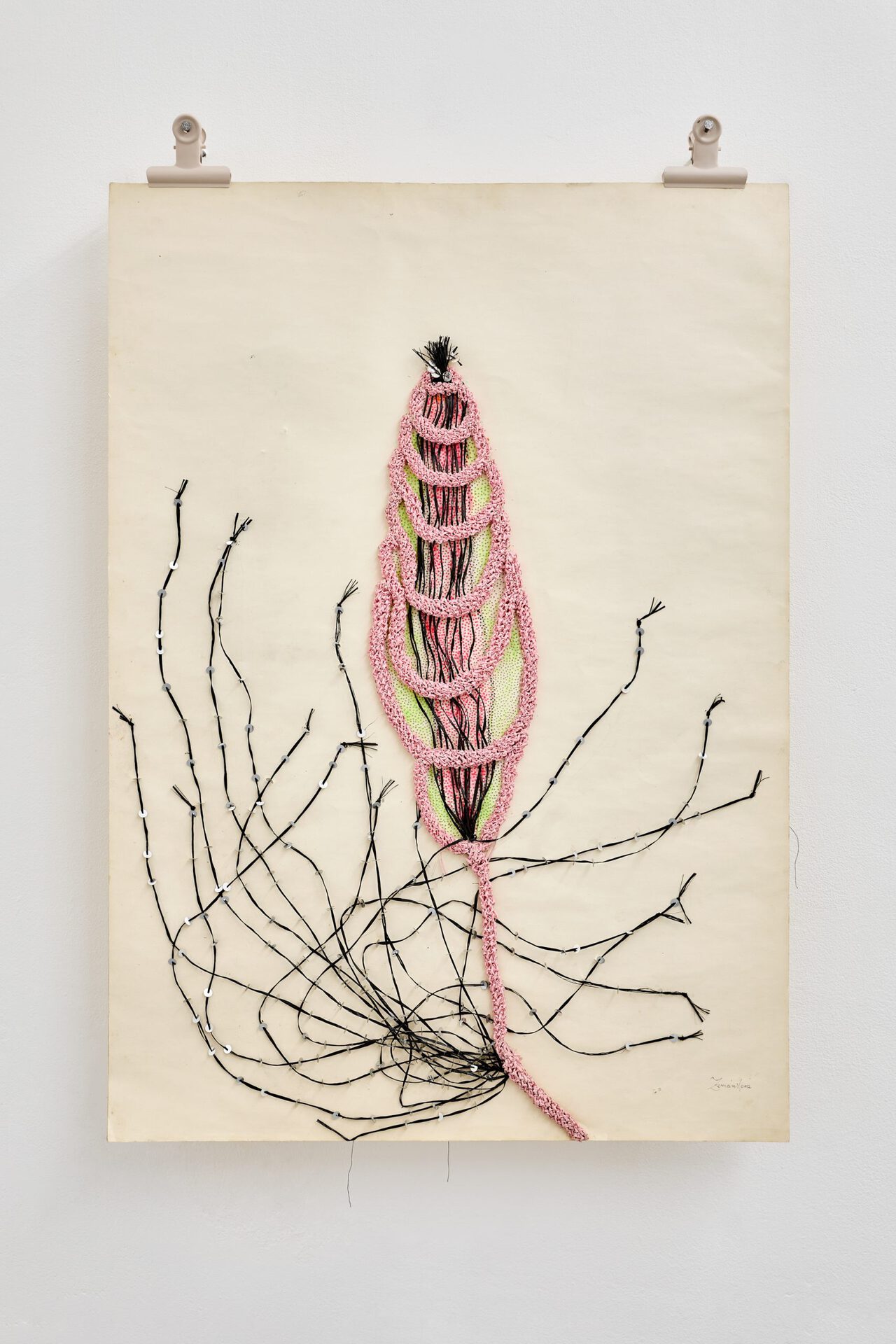

Initially, the artist worked with pencil and tempera paint, watercolour, then with dry pastel, oil pastel, and crayons. The details were first marked with ink, then a pen and marker. There was a time she used to cover her drawings with cooking oil to seal them - it didn’t occur to her that the oil would soak in and leave an unsightly stain around the contours. She composed collages out of paper snippings, then sewed beads and sequins into them. She used a needle to punch a paper placed on styrofoam and printed onto it using blind blocking with blunt objects, then fixed these protrusions in a relief. She starched, cut, and painted synthetic satin.

All of that took place on her kitchen table.

To Become Her Own Person—The Life Of Anna

It’s perhaps only in the details where one can see that the hand of an older person drew them with no artistic training. Anna Zemánková (1908-1986), already at an early age, painted landscapes based on postcards and showed interest in studying art. However, she followed her parent’s advice instead and was trained as a dental technician, opening her practice in Olomouc. At forty, she moved with her husband and children from Moravia to Dejvice in Prague. In 1960, her sons found a small suitcase in the attic that was full of paintings. When they learnt that she was the author, they persuaded her to return to making art. This was because they felt that their mother was going through a personal crisis - she was experiencing long-term discontent. The children had long left their nest and didn’t require her care anymore, the relationship with her husband also wasn’t harmonious. She was holding in an inordinate amount of energy that needed to explode.

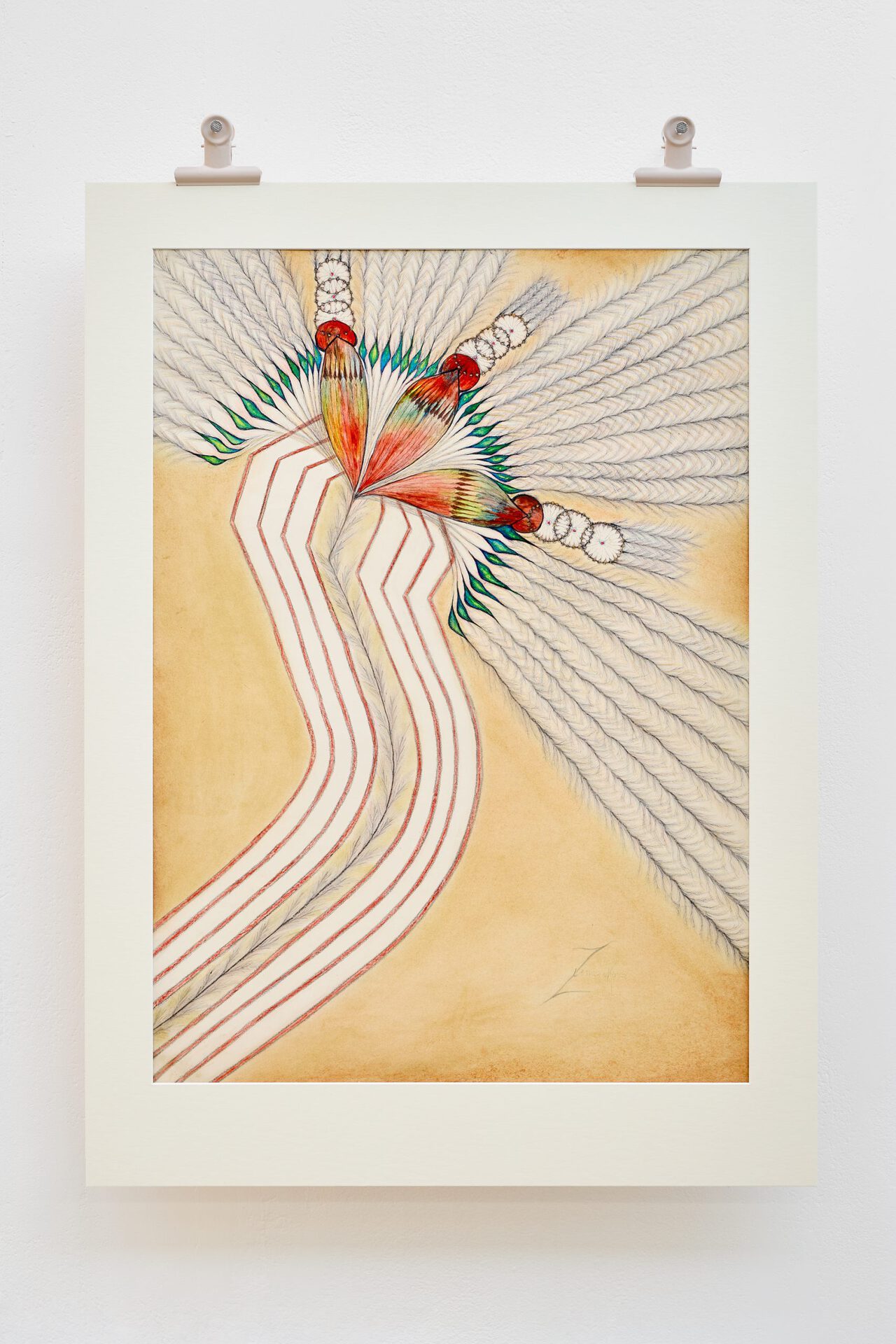

Zemánková’s artistic work soon became a form of art therapy and she succumbed to it completely. Similar to the other representatives of the art brut category, in which she is usually included, her yearning for a creative realisation arrived out of the blue - not in her youth, but when she was middle-aged. It was a means of self-preservation and pleasure - the meticulous work brought her satisfaction and even a deeper potential of becoming “her own person”. She used to wake up around four in the morning and started to paint while listening to classical music, unable to create in silence. These morning seances, somewhere between night and day, between dreaming and awakeness, became a ritual. Her hand first covered contours of the largest volumes, then it resorted to shaping the smaller units, and finally, it came to the lacing of tiny details. Her dentistry practice then manifested itself in the miniature details - in almost filigree fillings and arabesques of her artworks.

Art was becoming a more and more significant centre of her life. The author immersed herself into inventing new techniques with a childlike vigour and had a strong desire to exhibit her creations. Zemánková organized Open-Door Days at her home, where she invited her neighbours and also her children’s friends from the art world. She would hang her artworks on the walls, on the improvised boards, and even on wardrobes. When, in the sunset years of her life, first one and later the other leg had to be amputated because of her diabetes, she moved to a retirement home in Mníšek pod Brdy, where due to the limited space and motor skills she created increasingly minuscule artworks until the last moments of her life.

Atlas Of It All—The Framing Of Anna:

Zemánková’s artworks usually find themselves in a more formal environment, more often in the context of modern art and art brut, than contemporary art. They are frequently dressed in mats, framed, and displayed under glass. Here, we can meet them naked, which makes them somehow lightened and more youthful. The nakedness allows for the truth of the circumstances of their origin to come out - thanks to the various stains and impurities on their margins - as well as the fact that some of the artworks of the same series slightly vary in size or similar. This exhibition thus unintendedly manages to thematise the aspect of institutional framing - in the philosophical as well as literal meaning. The project resembles more an anthology than a retrospective. More than an effort to write an encyclopaedia definition, I aim to tell a sensory tale without objective criteria, to illustrate (and truly, even amplify the impression of) the evolution from the concrete shapes to more abstracted signs, from tempera and watercolour towards pastels and other techniques, ending in the room with vaulted ceilings by artworks characterised by the use of synthetic materials and sculpturally emerging into space. The notice board and the table might remind us of the artworks’ origin on the kitchen table and the activity of pinning on the notice board on the Open-Door Days.

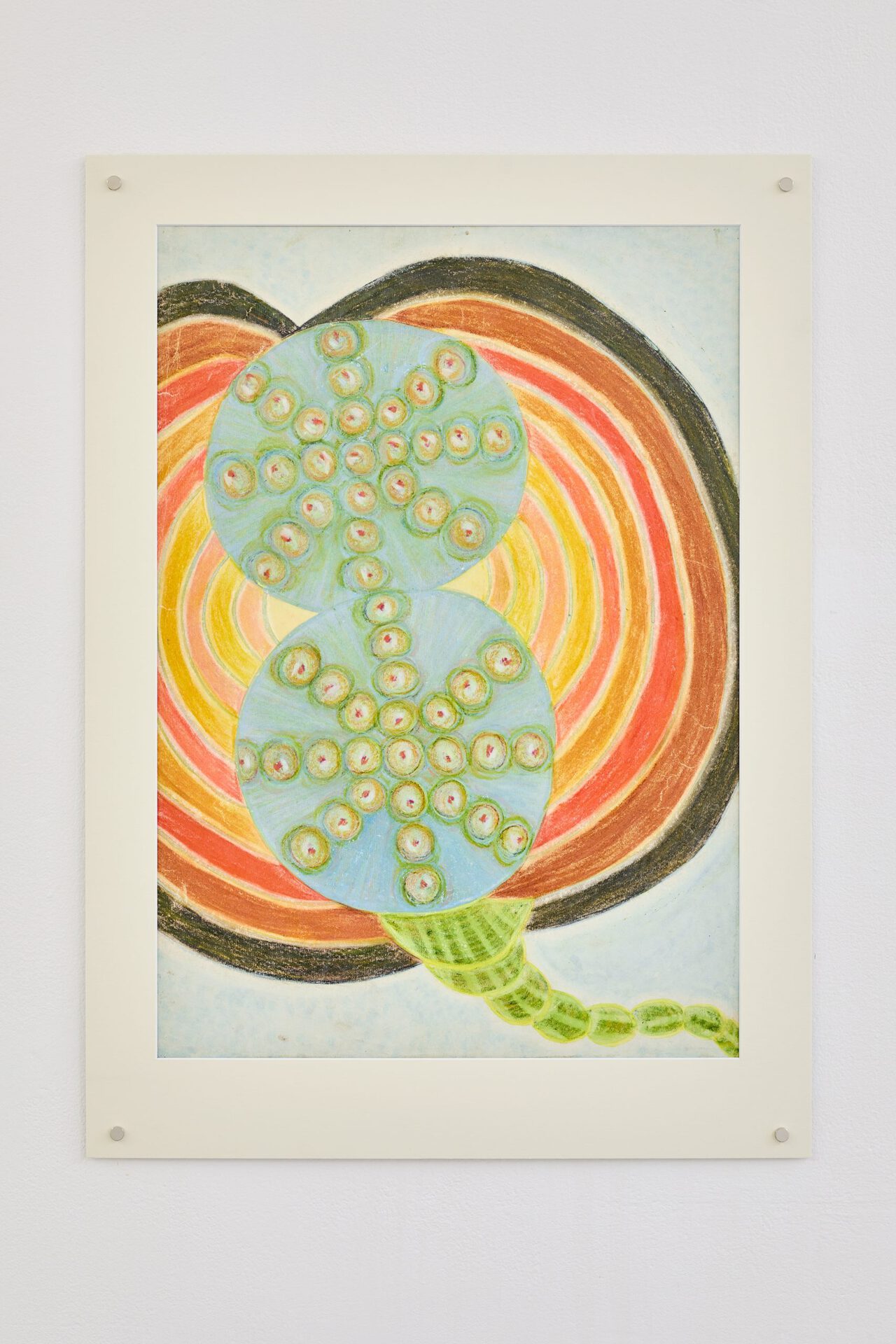

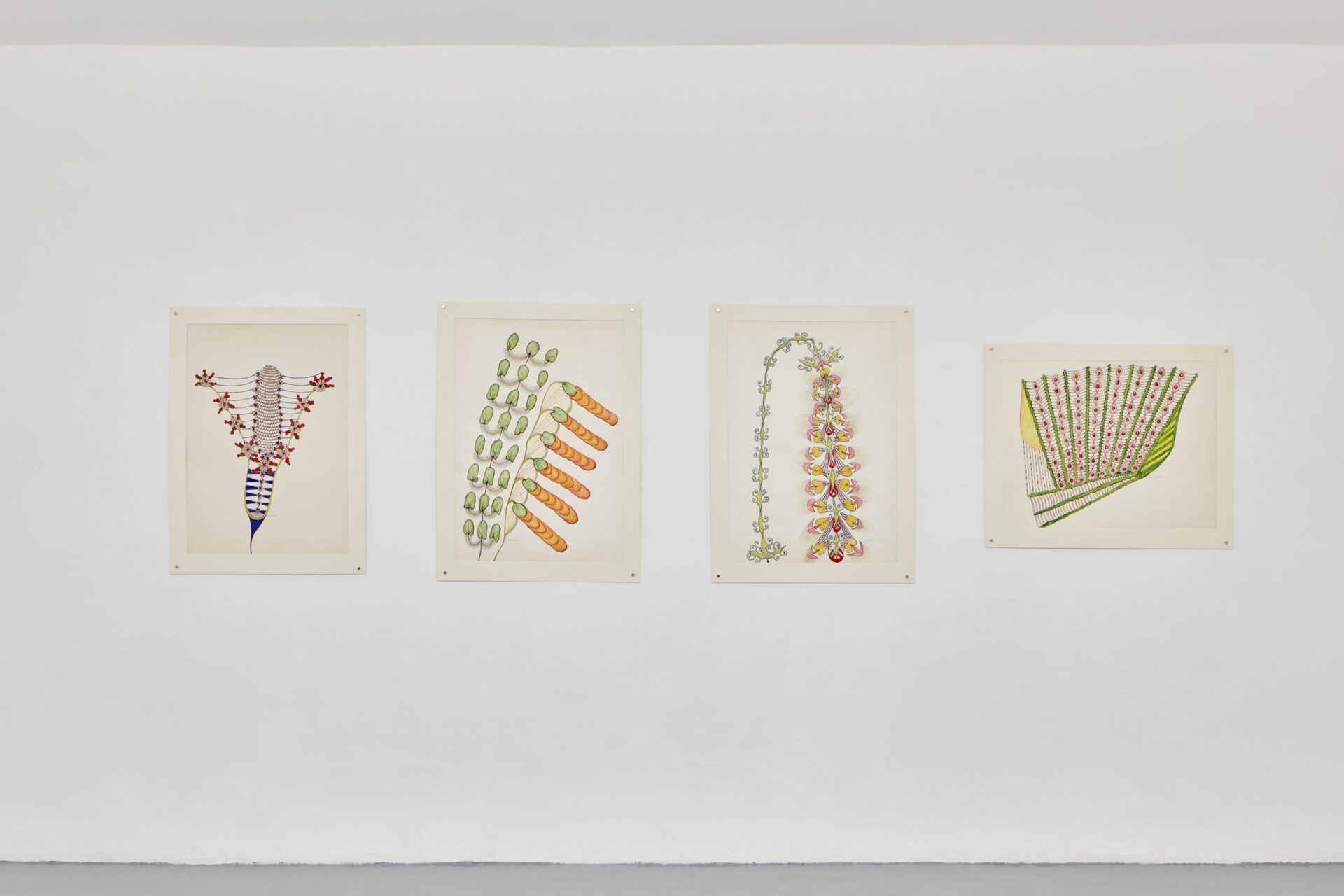

In the first room I see objectification of ontology - the image of cell division of a maggot in an apple was destined to open the exhibition. Two quartets of artworks from the early 60s offer the comparison of the more concrete and static, almost herbarium-like line, in opposition to a more abstract and dynamic, conflicted one which sticks its fiery, poisonous tongues out on us. It gives us the opportunity, for the first and the last time, to observe watercolour - a technique that the author soon refrained from.

The second room under the glass ceiling opens with two pastels that were created as a parable of the birth of her two sons - Slavomír and Bohumil. It’s their first opportunity to hang next to each other and to function as a memento of motherhood, which the author herself considered being her key role. On the pillars, we find four totemic, meticulous drawings of stunning detail that the sun touches at least sometimes. The wooden board by the light is inhabited by, among others, shaggy-looking butterflies that haven’t been shown yet.

Pastels from the second half of the 60s dominate the largest room- the extensive color scale of this material allowed for a simple layering, solid line, and provided superb control. This soft material especially appealed to Zemánková. At that point, she was already suffering from glaucoma, which gradually blurred the edges of her vision into the dark, and similarly, she lightens up the centres of the paintings here. She brilliantly draws the flowers’ curves, as if they were magical shields or petrified animals.

The small, hybrid room evokes a darkened cosmic cabin infected by alien protozoa and berries of slime. Here, drawings are characterised by the gradual simplification of the sign, and a more rounded shape. The wooden boards, originally from the decorative wall of the flat in Nusle, seem to talk in the language of runes.

Four pictures are hanging in the hallway that are inspired by Cubism, more in their visual aspect than content. Zemánková didn’t build a relationship towards the history of art, but we can imagine that from watching TV she was familiar with eminent artists the likes of Picasso, and at one point she indeed set off toward geometrisation in abstraction. These attempts were merely epigonic, though, and she soon steered clear of them.

Subsequently, the author worked mostly with synthetic satin that she dyed and glued to paper. In the room with a vaulted ceiling, we discover examples of this practice on the six pieces of jolly herbarial neo-forms. The monumental artworks on the wall at the back represent the peak of her oeuvre using paper, which she frays, layers, folds, and models skilfully. The three works crocheted from plastic bast even arise from their format and seem to release themselves from their surface. At its end, a brown pastel drawing symbolically sums up the entire exhibition, and its pores lay bare the plant atlas of it all.

—Lukas Hofmann

Lukas Hofmann