Archive

2021

KubaParis

a-plotless-horror-movie

Location

Museum Kurhaus KleveDate

19.03 –23.05.2021Curator

Marie Sophie Beckmann and Julie RobiollePhotography

Katharina SiemelingSubheadline

Holly Childs & Gediminas Žygus, Istanbul Queer Art Collective, Sarah Margnetti, Tabita Rezaire, Liv SchulmanText

As a feeling that seems to have permeated everything that used to be mundane, discomfort still is a culturally volatile, socially slippery sentiment. The various conditions of precarity and instability it’s stemming from are nevertheless both highly topical and inscribed in a long history of unevenly distributed privileges. Investigating affect as “what sticks, or what sustains or preserves the connection between ideas, values, and objects,” (Sara Ahmed), a plotless horror movie invites you to curiously and critically engage in discomfort. Taking the history of the Museum Kurhaus Kleve and the surrounding gardens as its starting point, the exhibition asks about this feeling’s past and ubiquitous presence, exploring discomfort as both an intimate feeling and collective situation. The five works commissioned for this exhibition include an installation in the halls of the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Bad by Sarah Margnetti and four scores by Istanbul Queer Art Collective, Holly Childs & Gediminas Žygus, Tabita Rezaire, and Liv Schulman. They come in audio and text format and are available online.

Museum Kurhaus Kleve is a 19th-century bath house-cum-museum, surrounded by a vast baroque park, where physical wellness was paired with social leisure.

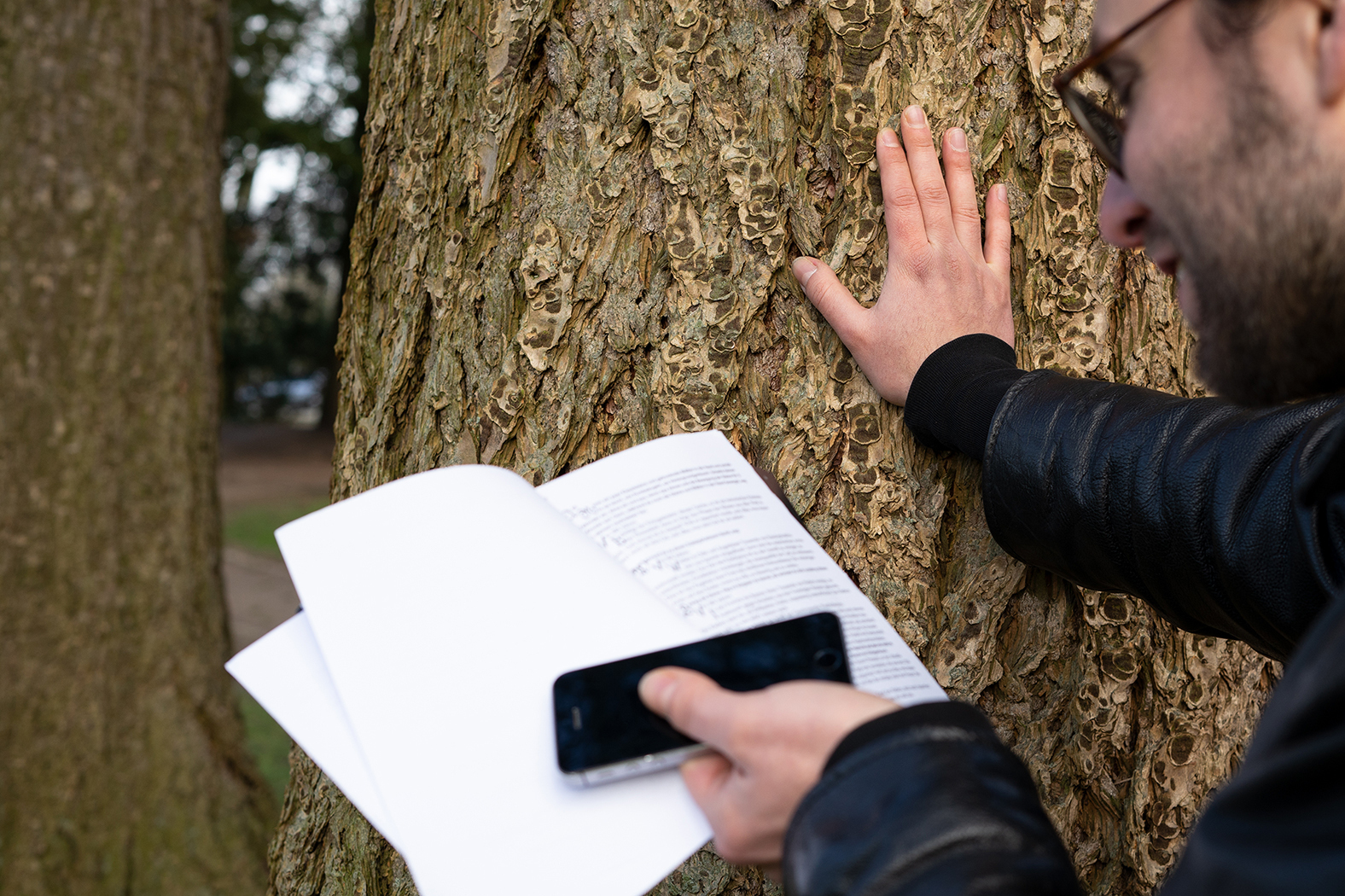

Bath houses and spa towns have been inspiring a number of horrifying scenes and stories, most famously the unsettling Nouvelle Vague movie L’année dernière à Marienbad (Alain Resnais, 1961). Using the concept of soft horror as a tool for disorientation and discomfort, artist duo Holly Childs & Gediminas Žygus turn Kleve and its gardens into a quantum portal that is entangled with all other colonial gardens in Europe. The perfect setting for a heist to happen and a detective story to unfold! Act Like You’ve Just Blown In From Nowhere is both an adventure and an investigation into the invisible violence hidden in our everyday environment.

After long strolls, the Kurgäste gathered in the bel étage of the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Bad to enjoy drinks, games, and a privileged view onto the Kleve gardens.

It’s for those rooms and their windows looking out onto the “Forstgarten“ that Sarah Margnetti created two pieces to partially cover the precious view. Hideout and Hearing, Healing, Caring are curtains that also pretend to be curtains, mimicking the depth of folds and panels of a heavy textile surface. Playing with deceit, the curtains expose the porous border that only seemingly separates the interior from the exterior. The technique of textile assemblage, a mise en abyme of Sarah Margnetti’s own practice of using her body parts as models for her pieces, reveals the awkwardness of one’s anatomy as an assemblage of symbols and imagery that don’t belong to us. In the center of Hearing, Healing, Caring, a baby-like figure appears, enclosed and distorted. The image of twisted limbs is inspired by reflexology and Auriculotherapy charts. According to this therapeutic technique in Traditional Chinese Medicine, areas of the body, organs, and physiological functions are reflected in our ear: the inside turned out and vice versa.

Peeking through the windows not covered by the curtain, the gardens come into view. Brought to Kleve by the governor of Kleve and former governor of Dutch Brazil, Johann Moritz von Nassau-Siegen, in the 17th century, the park that still surrounds the museum today is an example of what used to be state-of-the-art garden design. Its configuration is rooted in a symbolical and hierarchical ordering of the world. Kleve is thus a prime example of how nature in the 18th and 19th century came to serve as a place of leisure and comfort, sense and meaning – albeit only when governed, controlled, and, literally, cut into shape, since arbitrary growth and wilderness presented a source of discomfort that had to be controlled and put into mathematical order and causal logic. This approach not only reflects the organized depletion of both ecosystems and cultures in the New World by Western colonial powers but also testifies to the long development of the ideological act of rationalizing and hierarchizing people and landscapes.

With Landing, Tabita Rezaire offers us a meditation on our relationship to our earthly heritage. Here, realizing that we never exist in a vacuum, that we are not singular but in fact connected to what has been before and what will come, is a double-edged sword: honoring this truth comes with responsibility, but there is comfort to be found in acknowledging discomfort.

Discomfort is an affective state of general uneasiness and ambiguity. Stemming from no identifiable source, it often leaves one feeling both exhausted and restless, edgy and fatigued, alert and distracted. In the words of Sianne Ngai, discomfort can be thought of as an “ugly feeling:“ Neither passionately grand nor noble, nor romantic, docile or quiet, discomfort fails to offer emotional, purifying release. It is a feeling that describes neither excess nor lack; rather than motivating any action, it seems to suspend it. In its flatness, ongoingness, and non-cathartic character, it is perhaps best described in metaphors: the experience of badly worn shoes, whimsical exhaustion, or a plotless horror movie.

As such, discomfort is a state particularly well known by those who have historically been confined to the domestic sphere, namely women. In the closed space of the family and the home, women have, on the one side, traditionally not been allowed the emotional release of exploding into screams, cries, or laughter. On the other, the very term “emotions“ has for the longest time been associated with and used against the triad of the personal, the body, and the feminine, which in turn stands in alleged binary opposition to the objective, the mind, and the masculine. Discomfort – like the lingering bad taste on the tongue of silenced emotions – thus also comes with the weariness of denied agency and of being a forcedly passive witness to the political outside.

Forms of languages and address that reappropriate positions of marginality are part of the tools that Istanbul Queer Art Collective use in their queer reenactments of Fluxus scores. Understanding failure as a potent source of discomfort, their audio guide takes us to the fine line between discomfort and care, provocation and gentleness. The four poetic yet matter-of-fact tracks comprising their audio guide challenge us to question our relationship to the ordering of gender, sexuality, and nature. Assuming that discomfort is an almost primal state, they even render the lust for comfort an uneasy path.

Naturally, discomfort matters in crucially different ways; particularly in this time, as it is a feeling that varies according to one’s privileges. While suggesting neither a universal reading nor a precise definition of what discomfort is, a plotless horror movie assumes that this particular feeling can, at this particular time and place, be made productive as a critical and collective tool – as an affective mode of inquiry of what is otherwise hard to grasp. When approaching discomfort from this perspective – and during the currently forced revival of the domestic space – questions arise about how the self and other, private and political, interior and exterior, visibility and invisibility, interrelate.

“In a situation that doesn’t look like whatever we are used to knowing anymore, and has not yet become something that we can actively imagine or predict, I’m going to write a score for you.“ Liv Schulman invites “people living in Kleve, people able to go to Kleve, and people with the ability of imagining Kleve’s gardens and the will to perform a score“ to perform the series of score-scripts and to become a voice in her piece A Thousand Soldiers.

Walking in the gardens today, letting one be guided by the scores conceived for a plotless horror movie, what is brought to our attention is how Kleve’s history is crucially interlaced with class-, race- and gender-specific notions of (dis)comfort. Site-specific but not located, the scores can thus be understood as frameworks and generators for explorations that don’t require physical presence at the exhibition site, yet, potentially, create a feeling of proximity to it. The scores might be thought-provoking, healing, or teasing. They might invite imagination and speculation, and require one to leave one’s comfort zone, embrace moments of awkwardness, and accept that there is no immediate relief or no easy solution. Most likely, they will, for the better, raise more questions than offer answers – and, incidentally, let us perceive the Museum Kurhaus Kleve and the surrounding garden landscape in a different way.

Marie Sophie Beckmann and Julie Robiolle