Archive

2021

KubaParis

A Thinnest Thin

Location

stanley brouwn pavilionDate

17.12 –04.01.2022Curator

Reinier Vrancken & Rabin HuissenPhotography

Charlott MarkusSubheadline

Reinier Vrancken & Rabin HuissenText

Introduction

I once had my breath guillotined. I was about to say something really profound before I was right before the first syllable interrupted. I drew in the breath that on its way out would throw whatever it was I was going to say into the not

me, but then I swallowed w, h, a, t, a, f, a, l, s, e, s, t, a, r and t. A false star and a false start.

I was given a poem the way newsreaders in the middle of a broadcast are handed by a hovering arm an ominous note saying something that whatever it is it cannot wait. Guillotine. Either because of the thinness of the paper or the sharpness of the words in the poem. When thin is at its thinnest, thin and sharp are one and the same.

It makes me wonder how long it would take to cut through a finger with a piece of paper. I suppose it depends on what is on the paper. Whether the paper is empty, a music score, a drawing or a poem. In any case I think it takes less time to cut through a finger with a piece of paper that is a drawing of a knife than it does with a piece of paper that isn’t really anything, just paper. Five cuts.

Out of that finger comes your ghost to wrap itself around you like linnen around its pharaoh. Let it check your body for ticks. Also, your ghost wrapping makes you look like a mirage.

By far the cleanest pass through a finger would be with a piece of paper that is also a one word poem like the ones written by Aram Saroyan. Do you remember his poem lighght? Kniiife for a long swift cut made by a sharp cleaver or knifffe, for the jagged cuts of a dull breadknife.

Imagine you cut off the tip of your finger with one of those poems and you leaking out of yourself like smoke emanating from a cigarette. You could draw messages in the air with it. James Lee Byars said that the perfect love letter is to write I love you backwards in the air.

/

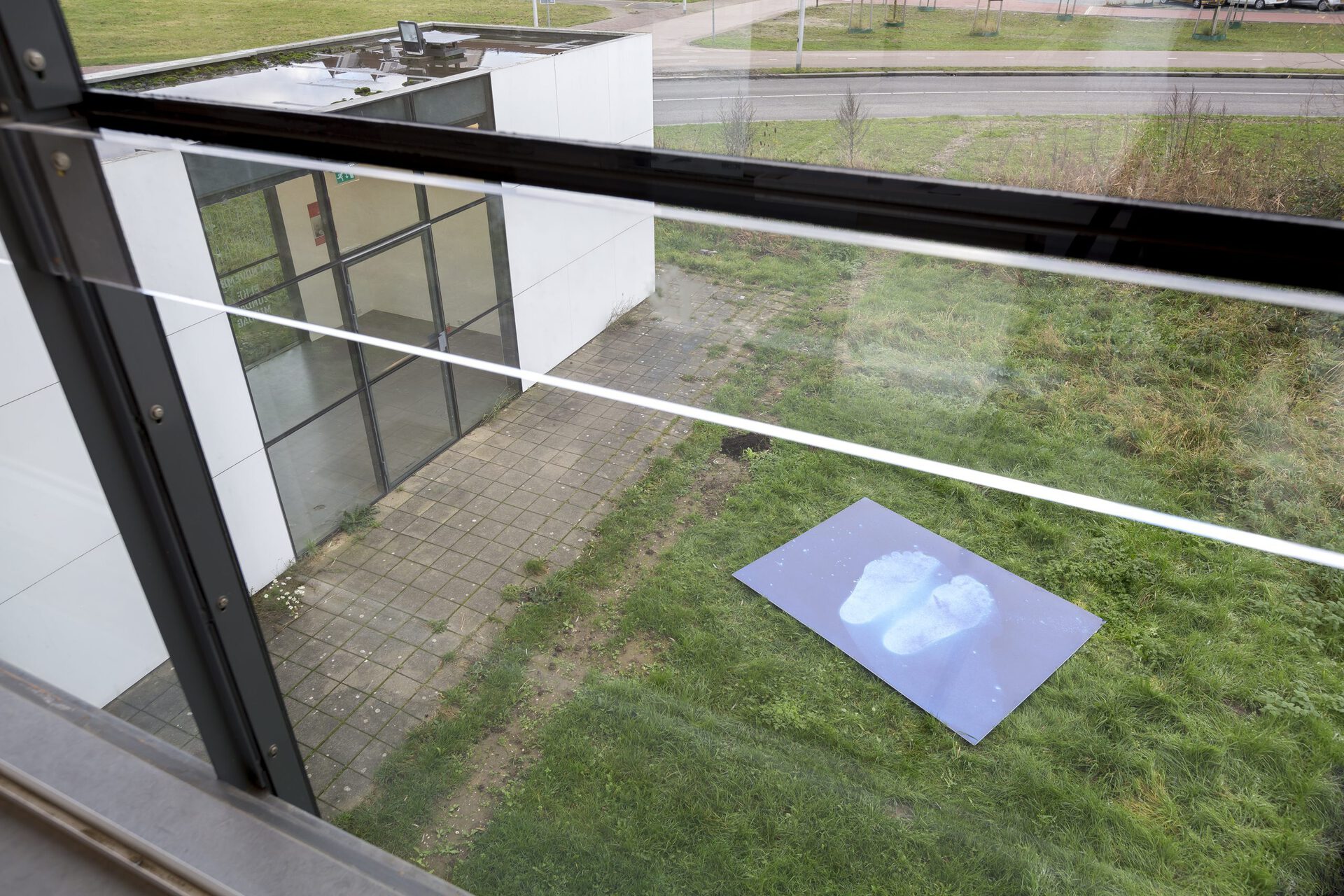

Rabin Huissen and Reinier Vrancken exhibit together in Het Gebouw, a building by the godfather of Dutch conceptualism, stanley brouwn. Their exhibition is the result of an exchange of thought between the artists and a dialogue with the pavilion, that is both sculpture and architecture. It was completed in 2005 as part of the art project Beyond Leidsche Rijn. What are now construction sites used to be uncultivated fields of grass. The pavilion consists of two elongated volumes, stacked on top of each other, based on stanley brouwn’s unit of measurement, the sb-foot, that is used extensively in his artistic practice. This exhibition is an experiment in which the practices of Huissen and Vrancken meet and situate themselves within the formal and conceptual framework of Het Gebouw. What connects Huissen and Vrancken is an intimate, perceptive, and at times poetic concentration that is so characteristic for their practices. The works can be subtle, yet, at the same time, communicate big gestures. Both artists start from an idea, an investigation into form and action, which sometimes results in an art object, or in a performance, or sometimes even in absence. The works of Huissen and Vrancken are on display in and around the pavilion, in search of resonance and connection with one another and the setting.

Rabin Huissen captures his presence in photograms. It is important where he is exactly, and what gesture he captures in the recording time, which has a certain length, that influences the final image. A photogram is an early form of photography, in which an image can be made onto light-sensitive paper. His recordings are performances in which gesture, time and location merge. This can last for minutes, a timeframe in which spontaneous influences help shape the image: brightness, climate, grains of sand blowing onto the paper, onto the body or the amount of motion made by Huissen himself. As a ritual, he washes the photo with liquids from the environment, sometimes water, sometimes a drink. Different layers of color and pigment follow, with each color referring to a day of the week on which he made the piece. The contact between fingers, hand or foot with the paper, the contact with the paper on the spot, are ways of recording the traces of an action, of his own presence. Huissen made a series of new works especially for A Thinnest Thin.

Reinier Vrancken interrogates meaning and signifier. With a poetic touch, he lifts objects or words out of their original context and alters something, subtly changes it, to reconsider their circumstances. Estranged from their primary situation, the forces at play that underlie specific meanings are made to move in new directions. By doing so, his installations raise the question of where one thing ends and another begins. Where does a body end, for example? Is a person expanded by his or her aesthetics, or is it the smell? Or the name? And what if a body is just one moment in a long chain of past and future lives? In his practice, the artist is hardly ever visible, but in this absence all the more present. His ideas, leaps of thought and associations determine the process and the final form of his works of art. In A Thinnest Thin he shows both new and existing works.

Machteld Leij (exhibition text), Reinier Vrancken (introduction)