Archive

2021

KubaParis

Beta

Location

forum presents / WHA GalleryDate

17.05 –26.06.2021Photography

Violetta WakolbingerText

One has the feeling that whenever he gets time, Brandmayr is to be found tinkering away with his ongoing chain of sculptural works: welding a screw to some wire here, hacking the bottom off of a plinth there, or figuring out what he can sandwich together to make an interesting object that defies gravity, shows the secrets of its own creation and amuses the viewer without being grandiose or taking up too much space.

Like his text description implies, there is a kind of recipe for life success buried inside Brandmayr’s sculptures - don’t take life/yourself too seriously, pay attention to the details, be aware that you are a part of the bigger whole. It’s also historically aware of itself. If you compare this work to the egos of modernism, this stuff understands its place in the world (and presumably, the storage system of the artist). Yet at the same time, there is a serious engagement with the concerns of sculpture - How do you put things together, How do you make them stand up, How do you best utilise the exhibition space and of course, What IS sculpture? For an exhibition at the entrance to an art university, it’s content is perfect, an understated example of what sculpture can do.

With the very first work you already get the idea. Forelle is super small, but neatly put together: a piece of laminated chipboard that looks like an offcut from something else is sandwiched into the middle of a cylinder made of poured concrete, which is wrapped decisively together using two pieces of coloured fibreglass smeared in coloured epoxy resin. 'Forelle' means 'trout', and it does look like a sporty fish. But actually the name is doing the thing down. It reduces the thing to one thing that it resembles. There’s an intentional reduction going on here, which sets you up for thinking that the whole exhibition might be about calling things by what they resemble. But as you will see, the naming doesn’t stay on this register. Looking at Forelle, you get the feeling you are looking at an experiment that perhaps didn’t quite go as planned, requiring the tape to hold itself together in the end. As a sculpture it has a whole story written into its materials. As a fish, it is standing on its nose, out of water, which is at odds with what is telling you as a sculpture, namely, “Here is what you can expect from the whole exhibition.” As you will see, these contradictions in meaning play a large part in the game of BETA.

Naming aside, the colour of the epoxy in Forelle raises further questions for me. Why is the concrete bound in purple and green? Colour always seems to be much more arbitrary than material or form to me. Despite this apparent randomness, across the whole exhibition the colours manage to produce balance, so there is clearly a kind of logic organizing everything. The artist is working from a small selection of colours that all seem to be centred around the sixth piece, a complex, side-squashed form of geometric complexity, like a Blender object that has been accidentally pulled sideways. It has a flat, sanded surface of grey, within which the colours of the rest of exhibition emanate in muted tones, their strong hues somehow amplified by being buried under greys. This work, Glücksstelle Moser, which means 'lucky spot' Moser (where Moser is a name like Brown, Smith or Jones - so maybe a friend of Brandmayr's?) serves as the central pivot for the other works, holding them all together with its weird angles and dim coloured light.

In one of several reverse moves that amplify the complexity of this seemingly straightforward exhibition, Glücksstelle Moser presents itself as a solid, weird monolith of some futuristic, toxic civilization gone wrong - or deeply right, right into itself and out the other side to where it stands, heavy on the ground in a parallel, sideways dimension. But actually the thing itself, if you dare to poke it, is deceptively light. It almost wobbles, the surface is brittle and only just hanging on. Where the other works revel in their honesty, this one is lying to your eyes through its teeth, its solidity barely there. The exhibition sheet, with its precise list of materials informs you of this – the thing is made of styrodur, an insulation material of puffed air.

The other two works that accompany and amplify the ‘lucky spot’ are simpler variations on the other materials at play in the exhibition: a narrow, bending tube framework of spot-welded heavy gauge steel wire that takes up roughly the volume of a person, the wires extending from a neatly shaped block of concrete daubed in luminous epoxy resin (Neo-Neo-Geo-Geo – is this a political comment of some sort, or just a fun double rhymey thing??? That’s left up to you). You get the feeling that the base is oozing, as if the ‘person’ is somehow sick to their core, and its got great feet that makes you think about cheeky lamps or some kind of funny metal flower. It’s colleague, Scala Integrale, is a mollusc-like miniature tent-like structure made of a grid or scale of sorts, that wears the basic colours of the exhibition on its outer shell like a kind of weird badge or indeed, another scale - a measure or metre of colour intensity. So as you can see, Glücksstelle Moser’s companions are like all good cartoon sidekicks, a pair of striking contrasts – the effervescent beanpole and the skulking dwarf.

Together, these three objects - the lucky spot, the mollusc and the bending tube, set up a focal point from which the other works of the exhibition extend. Their placement leaves room for the remaining works in the first room - Odysseus und der Home Button and ACME - whilst at the same time, they draw the viewer through into the second part of the exhibition where another cluster of sculptures await. Both of these side constellations are talking with one another, whilst also setting up their own stances and vibing off of the central lucky spot. The four in the back room seem to be a continuation and elaboration on the ‘rules’ of this sculptural set, whereas the two in the first room have specific things to say and diverge more perversely from the norm established by the others. Following the route I took when I first explored the space, let’s turn our attention first to the second room.

Serving as a kind of static museum attendant that draws you closer, Lotus also consists of thick gauge wire, this time notably coloured with yellow spray paint – whether by the artist himself or a result of a previous process is unclear. Like Neo Neo Geo Geo, the structure of this sculpture has been patiently formed by spot welding. We see where the paint has been destroyed by the process of heating as the structure was built, which creates a pleasing colour variation that again speaks to or answers Glücksstelle Moser. The top part of the sculpture, three screws bored into the underside of the ‘lotus leaf’ wooden top, have deftly had their heads sawed off and been welded directly onto the body of the sculpture. This feature serves to draw the viewer in, its specificity laid bare by the simple, empty frame. The honesty of this structure chimes with Forelle and is at stark odds with Glücksstelle Moser’s deceptive surfaces. The most figure-like in terms of its size, Lotus feels more like an unfinished model of an empty building than a person. The title, with its allusions to the plant and the car manufacturer, positions the structure more in a metaphysical space, its internal emptiness perhaps serving as a critique of brands of this kind, or as a sad cry for the tragedy of climate change and its effects on the natural world, its hollow innards joining forces with the upturned fish out of water, Forelle. Though all of this reading might be a bit of a reach...

Chances are, the name just felt right to the artist and it was partly chosen to allow the viewer to play these kind of games without being able to ultimately land somewhere definite. That’s part of the fun that arrives when one works in the way that Brandmayr does – exploring materials, processes and forms. The results naturally speak to one another and create a myriad of associations for the viewer, many that the artist did not intend. That’s the thing about openness. It’s a gift that keeps giving, in both directions.

The final three works in this room are arranged in a two-to-one cluster. Drunk in Public stands with Formpolizei, a somehow obvious association that again breaks its own rules: a drunk and a copper. But if the cop is just an inspector of form then it won’t care how much you’ve been drinking. By the looks of the drinker’s bright orange face, that’s lucky, because she/he/it is hammered.

Drunk in Public consists of what looks like a recycled plinth, which has been hacked at the bottom end to remove its secure connection to the ground. A delicate, symmetrical wire construct connects the blocky body to the simple ‘head’, a bright orange piece of laminated chipboard with a white back, which is kipped at a lairy angle. It’s this combination of areas of fine, careful detail and simple forms that lead one to explore this exhibition, understanding some elements immediately and needing to peer closer to inspect areas of interest up close. This variation of attention creates real movement within the space – the movement of an active mind wanting to explore this game of 'show and don’t tell' from all angles.

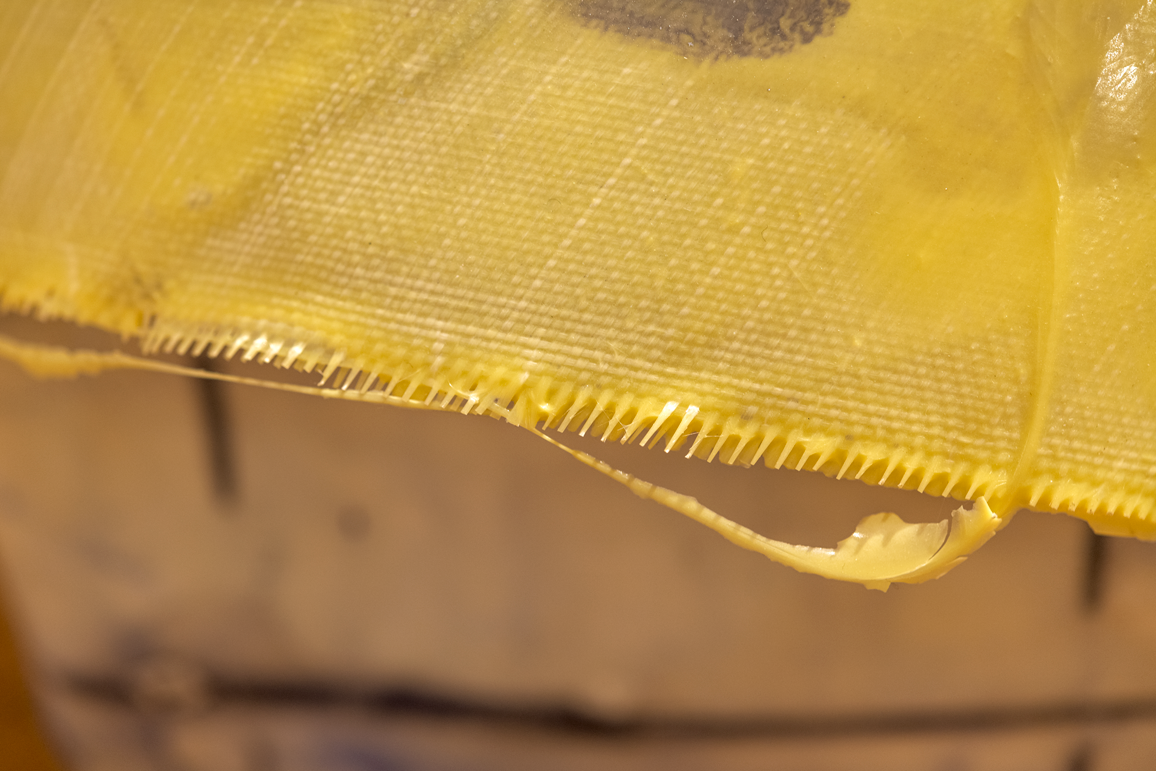

A low lump on the ground, Formpolizei is either crouching beside its drunken friend or lies there decapitated. This is the most annoying of the assembled works. Another shell like construct of fibreglass over steel, it has an additional strip of fibreglass in bright yellow draped roughly over the top of it, so that the thing resembles a riot gear helmet. It’s really ugly. An exercise in bad form, which the name sarcastically acknowledges. And of course the funny thing is, when one shucks past the shonky madness of the assembled works, it is clear that Brandmayr is paying very close attention to form, so the naming and the decapitation serve as further double bluffs. The sculptural head looks out over the other works with a keen eye, said gaze hidden under its garish visor, just as the artists intent is buried beneath self depreciating modesty.

While Formpolizei regards the assembled works, the luminous face of Drunk in Public points in the direction of Die Unschuld 2, creating a loop that gathers these three works into one group of characters, tied by the ‘gaze’ of these people-things. The most minimal work in the show, Die Unschuld 2 performs a low, private dance in its isolated corner that has our blazing drunkard mesmerized. Consisting of a short, L-shaped steel support through which a piece of steel wire has been ‘woven’ in increments of increasing length (another scala), its top parts point up aimlessly into the air. Meanwhile its lower end, neatly illuminated by the room’s spotlights, extends out along the floor to create a long arc that shadows the ground without touching, setting up a lovely relation with its own negative. At this physical ‘end’ of the exhibition, this near-kiss shadowplay strikes up a conversation through the wall with Odysseus und der Home Button, drawing the viewer back into the endless loops of the exhibitions twisted pathways. Before we turn our attention to that work, its worth adding that the title of Die Unschuld 2 plays a different game to the others. ‘Unschuld’ is ‘innocence’. Well, it might be innocent, but it might also be drawing the attention of the drunkard on purpose. You never know with these types of characters. What we can say for sure is that the ‘2’ establishes in the mind of the viewer a continuity of process that ought to be clear from the assembled works, but is here made explicit. Where there is 2, there was most likely 1, and will probably be 3 in short order, etc. The 2 reminds the viewer that these objects are being churned out in some weird chamber somewhere, with an airgun, horrible stacks of plastic, the remains of forgotten artworks, pieces of kitchenette and other weird materials laying about the place.

Where all that work is taking place is EFES42, Schillerstraße, Linz, studio and offspace gallery of Stefan Brandmayr, Felix Pöchhacker and more recently, Christel Kiesel. The focus there is on sculpture in all of its contemporary forms. Brandmayr also teaches elements of sculpture at the Kunstuni Linz. As is clear from the exhibition, this is the work of an artist who has found their place and is able to use that position in order to radiate outwards, carrying elements of their wider life and interests back into the work. We see traces of teaching in the active play of the work and physical elements of EFES42 are carried in literally.

Moving on... As I said, Odysseus und der Home Button is playing a similar game to Die Unschuld 2, in contra position. Where Unschuld stays low to the ground, sculpturally independent, O&dHB isn’t standing on its own at all. This creates a contrast not only to Unschuld, but also sets the piece apart from all the others in the exhibition - a point further highlighted by its title on the floorplan, which is printed in a different font. Where the others are all very much in contact with the ground and involved in some kind of act of balancing and supporting their own weight directly, here, only two of the four ‘legs’ reach the ground. The other two mirror Die Unschuld 2 by hovering millimetres above the floor, talking to their shadows, which this time are created by the piece itself – O&dHB contains its own light.

In order to produce illumination, such a sculpture must be plugged in. Normally this requires a cable being lain neatly across the floor to the base of the plinth, a constant ‘problem’ for sculptors that denotes the end of the work and the beginning of real life. Dodging this, O&dHB uses the architecture of the exhibition space, the light rails above, to hold itself up - as if it is also drunk. With a name like Odysseus, it might well be somewhat inebriated whilst on its exciting, vital adventure, the fate of an entire nation hanging on its shoulders... The impression of excitement is created here through the coiled cable of the light at the centre of the piece: Odysseus has finally found ‘his’ way home! But again, one gets the impression that this odyssey is another critical comment on modern life. The cable that holds the sculpture reaches up into the ceiling and away into the grid, in much the same way that the internet alluded to by the Home Button of the title also leads away from most modern homes. We can all recognise this dependency on outside sources of energy for our own daily doings, clinging as we often do to outside sources of power and entertainment to get us through, rather than getting off our arses and doing something active to resist.

The final work to tell is ACME, another inversion in relation to O&dHB and Die Unschuld 2. Placed on the low shelf of the gallery’s main window, hte other side of the univeristy rubbusih bins, ACME presents itself as a bedside or table lamp, even sporting a neat plug with on/off switch. Here all of the ingredients of the show coalesce in condensed form – steel, fibreglass, epoxy resin, concrete, lacquer, chipboard, cable with switch, a source of illumination and of course, self depreciation. From the placement, the execution and the name, this work could almost be a genuine item for sale – if there was a shop for toxic, abrasive wild looking household items (which there probably should be…). Of course, as with all the other works in the show, one gets the impression that Brandmayr is acknowledging the irony of his position – most likely, no one will buy the thing. Though I must admit I am tempted.

Contemplating ACME leads us back to the entrance of the space and the start of the exhibition, a good place to conclude. For me, this work does what I want sculpture to do in an art space. It leads me in, takes me round, makes me want to crouch, peer, poke, sniff and laugh at the whole, and the parts thereof. It uses variation to set up contradictions, echoes, conversations and loops. It uses titles to create specific associations on a range of meta planes, allowing me to understand the work in all of its specificities, as a part of the larger art conversation and as a critical / poetic reflection of this mad modern world of ours. The materials chosen complement these reflections nicely, causing an uneasy sense of fascination and disgust.

For me, the tragedy of this work is that it probably won’t be seen by enough people, and it might not be understood by them if they don’t have an art education and an open mind. I fear there is too much apparent ugliness and unfinish for most eyes to be able to see what is directly in front of them. Perhaps I am wrong about that. I hope so.

In his email to me after I started writing this, Stefan very directly stated that 90% of his sculptures have already been recycled. He described enjoying seeing parts of his old works pop up in works of the current Kunstuni students, who have picked his remains out of the rubbish to repurpose into their own creations. He also made reference to various old artworks that have made their way into his pieces. Something from Thomas Kluckner’s work for FMR in 2019, and another part from Noele Ody and Rainer Grilberger’s exhibition at EFES in January this year. There are also parts of a kitchenette involved – the bright orange pieces. This very Zen approach to art making is to be admired and perhaps also queried. As can be seen here, process based art making done well can produce wonderful constellations for the mind and body.

Having worked for a short while as a shop fitter in London, I am often struck by the similarity between the junk production of contemporary art practices and these kind of neoliberal makeovers, where entire rooms are stuck together with hot glue, finished with spray paint only to be ripped out the following season. Of course, Brandmayr’s openness to the void, and acceptance of the continual re-use of materials goes some way to 'solving' the idea of junking. But there is something about this means of production that still makes me feel uneasy, even as I practice it myself.

Another query I have that relates to junk exists in the form of a wish or hope. Rather than existing on the fringes, in these spaces for a short amount of time only, why isn’t there a place, or PLACES PLEASE in this Linz world of ours where such works could form a part of the everyday landscape? Why isn’t there a coffee shop, library or public place for sitting that has been arranged and put together by Stefan Brandmayr or artists like him, where the ongoing, unfinished nature of these works can reflect back into the daily doings of ordinary people? The public seating works of Franz West spring to mind here as a kind of signpost, pointing to a place where the idea of BETA can bleed back into the polished veneer of most shared spaces in this city. That is what I wish for in this Linz corner of our mad world. But at least in the meantime, I can walk around with my head full of all that elegant, critical play. Cheers, Stefan.

Sam Bunn