Archive

2022

KubaParis

Blade Memory

Location

Dortmunder KunstvereinDate

20.05 –30.07.2022Curator

Naama Arad, I. S. Kalter, Eran NavePhotography

Jens Franke / Roland BaegeSubheadline

BLADE MEMORY II a cooperation of Dortmunder Kunstverein and CCA Tel Aviv-Yafo curated by Naama Arad, I. S. Kalter, Eran Nave 21 MAY – 31 JULY 2022 with works by Uri Aran, Oded Avramovsky, Marianne Berenhaut, Max Ernst, Avner Ben Gal, Noa Glazer, George Grosz, I. S. Kalter, Talia Keinan, Martin Kippenberger, Harel Luz, Roy Menachem Markovich, Lee Nevo, Tchelet Ram, Ariel Schlesinger, Shay-Lee UzielText

BLADE MEMORY II

curated by Naama Arad, I. S. Kalter and Eran Nave

Dortmunder Kunstverein

in cooperation with the CCA Tel Aviv-Yafo

21 May 2022 – 31 July 2022

With works by Uri Aran, Oded Avramovsky, Marianne Berenhaut, Max Ernst, Avner Ben Gal, Noa

Glazer, George Grosz, I. S. Kalter, Talia Keinan, Martin Kippenberger, Harel Luz, Roy Menachem

Markovich, Lee Nevo, Tchelet Ram, Ariel Schlesinger, Shay-Lee Uziel

“Blade Memory” is an exhibition in two chapters curated by the three Israeli artists Naama Arad, I. S.

Kalter and Eran Nave. Its title evokes an aching memory, a memory that strikes to the heart, which

should be understood on both a personal level and that of social developments. The artist-curators

see each of the works as a kind of holder of time.

Chapter 1 was shown at the CCA Tel Aviv-Yafo, and took a critical look at the idea of art as something

‘produced’. Chapter 2 at Dortmunder Kunstverein examines the role of artists whose present is

marked by the disenchantment that professionalisation, corporate branding and its architectures

have left in the individual’s sense of agency since early modernity. The world began to accelerate

increasingly in last third of the 20th century: densified inner cities leave little room for individual

expression; the time economy of digitalisation is optimising global effectiveness, creating not less but

more work for some and none for others. Structures of capital and power are consolidating.

The exhibition takes place in the shell of the new premises of Dortmunder Kunstverein, which were

formerly used as an insurance office. Artists and insurance offices are joined in a Kafkaesque love-

hate relationship that exemplifies social developments – but also awakens ambivalent memories of

bureaucratic coldness or of the predictability and stability that such places still emanate. Through

digitalization and the pandemic, vacant office space increasingly represents a turning point: the ruins

of the early 2000s office architecture now provides a space to look at the world in its status quo, to

order it, to contextualise it. Rather than exaggerating and overwhelming, the sober setting of this

backdrop allows the art to appear incidental, giving it a chance to reclaim its autonomy outside the

spectacle.

Some of the sculptures, drawings and paintings shown here deal materially or in their content with

simple everyday office materials, and are in search of a space of individual expression within the

institutional and bureaucratic grid of efficiency. At the same time they are objects that refer to

memories of the past:

The clock by Lee Nevo (*1984), with its somewhat ageing design, its hands pushing a mountain of

cigarette stubs around, or the wooden computer by Shay-Lee Uziel (*1978), in which a rabbit made

of spat-out sunflower-seed shells perches on a miniature table, can both be seen as homages to

slowing down – the artists’ response to the efficiency machines of digitalisation. As the drawing of a

photographic self-portrait after a shower, the work by Dortmund-born Martin Kippenberger (1953–

1997), probably from the year 1973/4 and exhibited here for the first time, is the equivalent to a

media doubling of memory. The drawings by Oded Avramowsky (*1956), integrated into office tracts

and furniture, bring about a conflict-ridden encounter between rationality and dream. And the

“Bread Library” (2020/22), by Uri Aran (*1977), which reproduces the Latin alphabet in carefully

sorted block letters, is a loavely collection of utensils for the production of text. The work asks how everyday activities can be used to produce meaning. The letters can notionally stand for all kinds of

sentences: poetic, bureaucratic, objective, academic, emotional, personal.

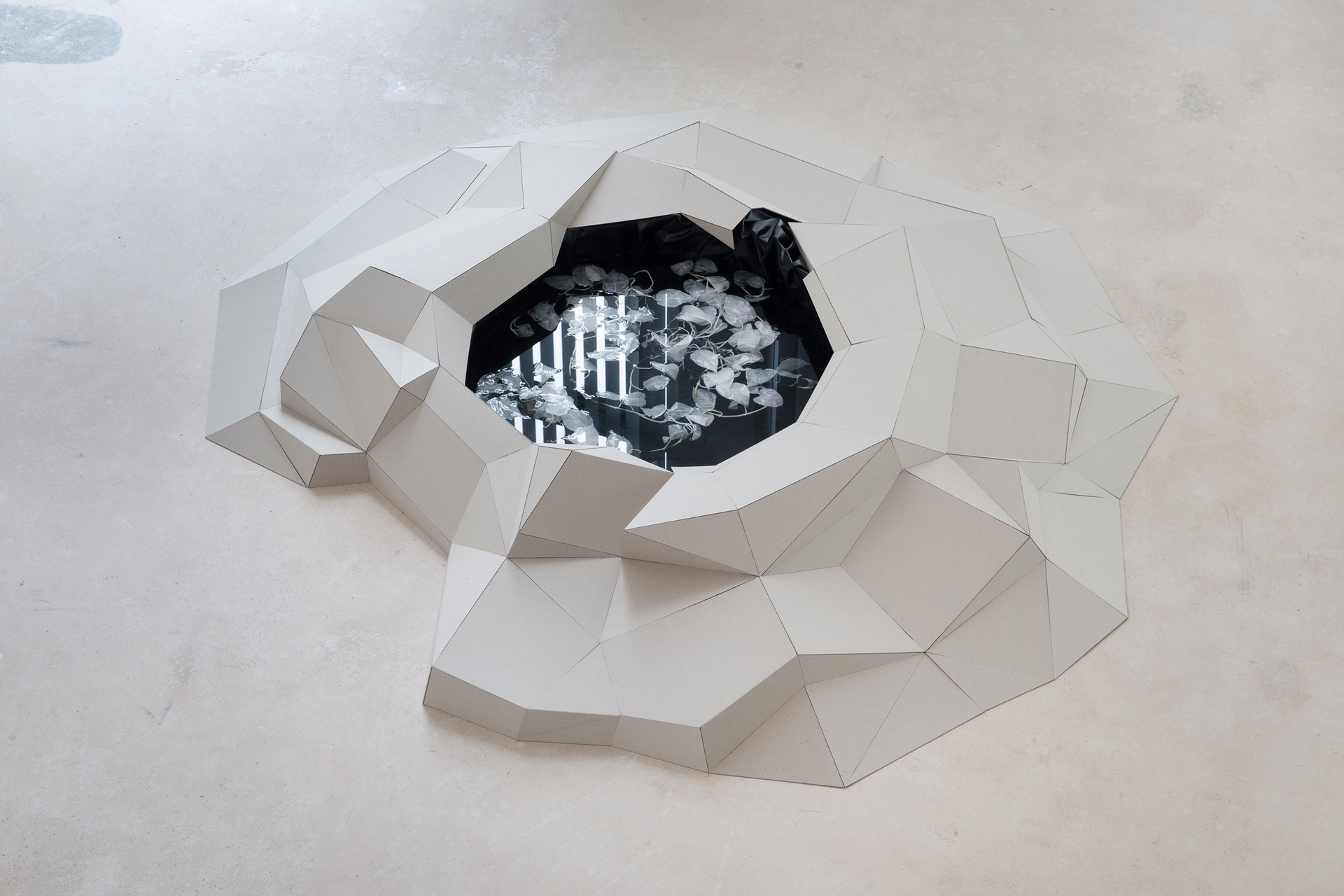

Plants bleached with cleaning fluid in the work of Tchelet Ram (*1982), a textile sculpture filled with

toxic glassbuds by Noa Glazer (*1981) or Roy Menachem Markovitch (*1979)’s modernistic

sculpture made of garden hoses and cables are examples of a poetic repurposing of everyday

materials in this exhibition. Markovitch’s sculpture looks something like the sketch of a sculpture in

the foyer of a bank, a place where for decades artworks have been used as the symbols of power and

expression of potency. This idea is underlined by the pharma company Pfizer’s Viagra pill enlarged by

Harel Luz (*1979).

The ascent to the gallery on the upper floor is a transit to the level of power, and is bathed in orange

light (a reference to Blade Memory I): in a carpeted room stands on oversized conference table. At

one end the sculpture “La Génie de la Bastille”, by Max Ernst (1891–1976) is solitarily enthroned. On

the wall hangs the 1919 lithograph “Der Mensch ist gut!”, by George Grosz (1893–1959), which

reflects the urban space around the Kunstverein and shows a company of three wine-drinkers, one of

whom has laid his knife on the table. Both artists were in their time part of the exhibition

“Degenerate Art” (1937), and can act as points of reference for how the past operates on the

present, and for the question of the place of artists in society. Perhaps to the accompaniment of that

unchanging song of power to which feathers dance on a record-player in the work by Talia Keinan

(*1978)? Or like the network of spider’s webs in the large-format painting by Avner Ben Gal (*1966)?

The metal branch as oil lamp by Ariel Schlesinger (*1980) heralds the atmosphere of the final space,

the ‘janitor’s room’: here a work by the Belgian artist and Holocaust survivor Marianne Berenhaut

(*1934) stands next to the painting Death belongs to the Realm of Faith, from the 18-part series of

Living Paintings by I. S. Kalter (*1986). Berenhaut’s broom is far too big for the small dustpan. An

imbalance common to the exhibition as a whole that raises questions about the toxic effects of

unequal power relations in the world.

Text by: Rebekka Seubert

“Blade Memory” was curated by the three artists Naama Arad, I. S. Kalter and Eran Nave, on the

invitation of Nicola Trezzi (CCA Tel Aviv-Yafo) and Rebekka Seubert (Dortmunder Kunstverein).

Naama Arad (*1985) works in sculpture. Her pieces were presented in a solo exhibition at the

Dortmunder Kunstverein in 2017. In 2021 she curated the exhibition “Show me your shelves” at the

Kölnischer Kunstverein.

I. S. Kalter (*1986) is the founder of the curatorial platform Ventilator, and has presented his artistic

work in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art (2021), at Zona Mista, London (2022) and elsewhere.

Eran Nave (*1980) works in sculpture and painting. Recent exhibitions have included a solo show at

the Tel Aviv Museum of Art.

Rebekka Seubert