Archive

2022

KubaParis

Neuzeit Grotesk

Location

Gunia Nowik GalleryDate

13.05 –24.06.2022Curator

Camila McHughPhotography

Katarzyna LegendźText

Neuzeit Grotesk

Julia Dubsky, Hannah Sophie Dunkelberg, Heike-Karin Föll

Curator: Camila McHugh

May 14 – June 25 2022

Opening: Saturday, May 14, 16:00-19:00

Gunia Nowik Gallery

Bracka 18/62

00-028 Warsaw

Neuzeit Grotesk is a font that the German designer Wilhelm Pischner created in 1929, a decade after the founding of the Bauhaus, and adjacent to the design school’s emphasis on minimalist simplicity, form as function and a pared down economy of means. While Grotesk is a synonym for a sans serif font, taking it for its homonym—grotesque—alongside Neuzeit, or New Times, makes for an evocative turn of phrase. A standard in the print industry in the final years of the Weimar Republic, the font fell out of use under Nazi mandate until a version was picked up again in 1970 for official German signage and traffic directional systems, including, for instance, the autobahn signs that guide the straight shot east from Berlin to Warsaw. You might also recognize Neuzeit Grotesk as the typeface of Gunia Nowik Gallery’s logo—the starting point for the associative reflection that spurred this three-person exhibition.

Can art be a sign of the times? A harbinger of the vibe shift? A reminder of a certain tautology in the notion of unprecedented times? Lately, there seems to be a kind of prescience in art’s perennial pendulum between abstraction and figuration, on the one hand, and between sincerity and irony, on the other. Heike-Karin Föll, Hannah Sophie Dunkelberg and Julia Dubsky’s work operates in the hazy space between these poles, and as such, has something to bear on what we could call our Neuzeit Grotesk, our grotesque new times.

Since 2020, Föll has been working on a series of extra-small, flat pictures. There is something radical in their almost eccentrically small scale. Committing to this format constitutes a position against the bigger is better expansionist mantras of the art market (and beyond), coupled with an attempt to pay close attention to economies of expenditure, drawing on Georges Bataille’s thinking on excess and waste. Föll’s small-scale canvases command a striking spaciousness, a capaciousness for contradiction. While painting has a long history of concern with its own flatness, Föll tacitly brackets a tired modernist debate to consider whether painting might glean something from the internal system of that flat surface we interact with daily—the screen. Electronic interfaces produce images via data, which Föll identifies as patterns, mechanically operable signs with meaning. Borrowing this logic, she positions the miniature formats as searching for paintings within the paintings themselves. What could a painting learn about itself—its flatness, its materiality, but also its weighty legacy, its enduring attempt to say something new (or even, somehow, true)—by masquerading as a kind of data processing? Föll mashes up a wide vocabulary of gestural abstraction: dragging, pressing, smearing, dabbing, scratching, pushing paint across the canvas in a systematic search, a continuous rehearsal. For what—a painting? Stéphane Mallarmé’s reflection in his The Mystery in Letters (1896) is instructive: “Writing, tacit flight of abstraction, takes back its rights faced with the fall of mere sound.”

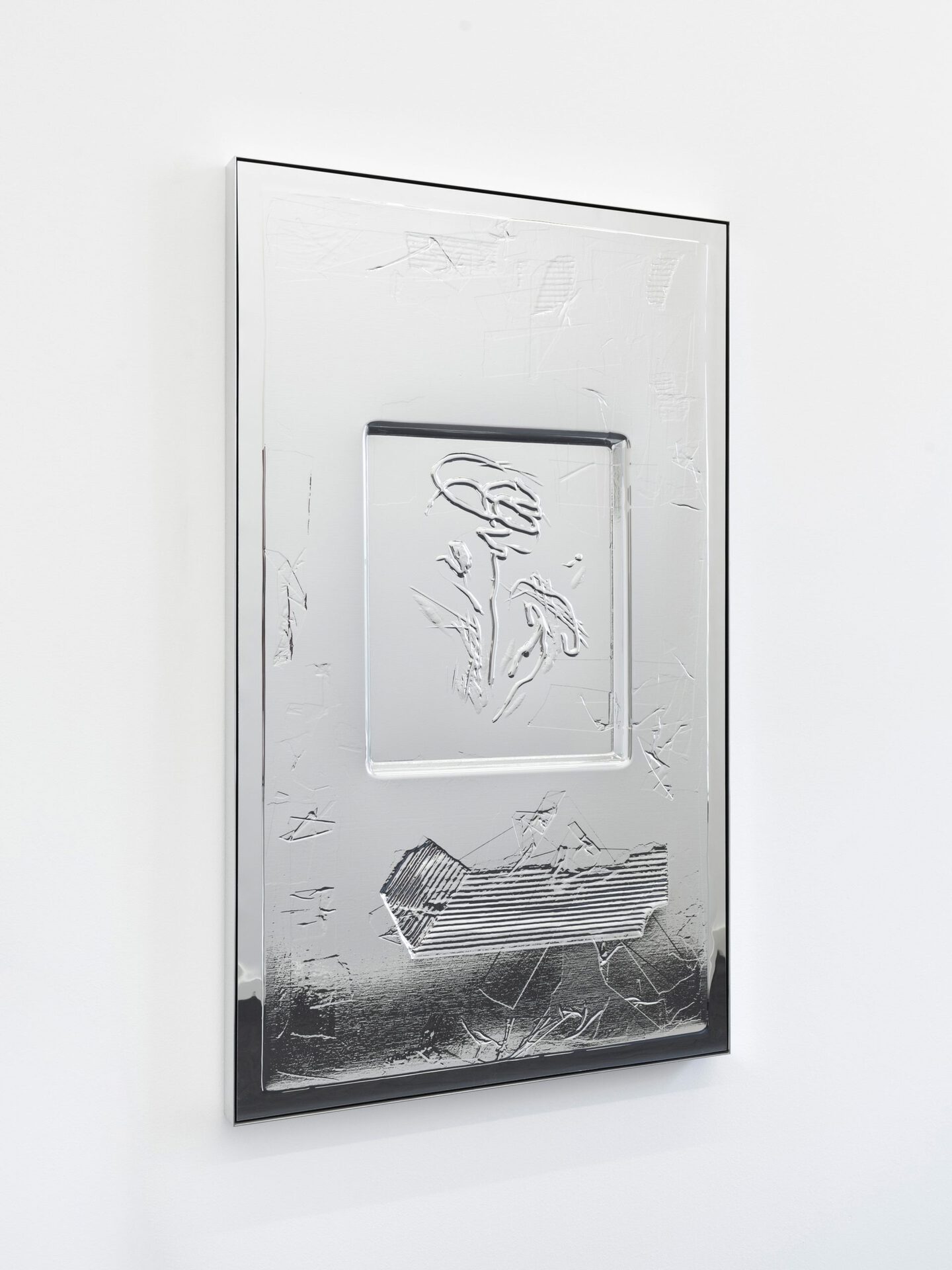

Like Föll’s paintings, Hannah Sophie Dunkelberg’s sculptures also emerge from experimenting with an unconventional, or even contradictory, melding of processes and techniques. Her wall reliefs, for instance, forge a mechanically-produced, inversion of her own gesture, in a method that involves drawing, wood carving, industrial vacuum forming, plastic molding and car lacquering. A scribbled flower stands at the center of her recent series of reflective, metallic reliefs, like a defiant, resurrection of hand-drawn, mark-making, against tightly-bound lines and haphazard scratches that appear like residue of a mechanical process. Dunkelberg cultivates a similar ambivalence, and sense of immediacy, in her massive, powder-coated metal ribbons, by choreographing tension between the works’ scale, material and the connotations of the neatly-tied bow. The rose—a classic grotesquerie, think the iconic lines from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), "He must have looked up at an unfamiliar sky through frightening leaves and shivered as he found what a grotesque thing a rose is…”—is a recurrent motif through Dunkelberg’s new works exhibited here. She handles the rose like she taunts the boundaries of sculpture—reconfiguring, renegotiating, rehashing—primed for the advent of precarious resolution.

With roses on the mind, the reds of Julia Dubsky’s shadowy figures might recall a particularly crimson bloom. She works primarily in three types of red oil paint and two types of blue, each with different material and tonal qualities. It’s as if in the midst of a meditation on color, a figure emerged, parting streaks and stains of paint like a curtain. The subtle variance between 4Actors, 4Actor and 4Acto is like a study in body language: a cocked elbow, a tensed shoulder blade. But also a study in futility, or a gentle prank—the point is not to suss out the differences between these inchoate forms. Dubsky identifies the figure as her own, positioning the series as a kind of masquerade of self-portraiture. She’s interested in acting; or the question of whether a painting can also act like, say, Isabelle Huppert does. Mikhail Bakhtin’s interpretation of the grotesque is also pertinent here, as he suggests that the grotesque image represents an incomplete metamorphosis, a state of growth or becoming. This is a space that is frightening and funny, straddles the real and the imaginary. It’s incomplete.

Camila McHugh

Exhibition partner: Goethe-Institut Warschau

Camila McHugh