Archive

2020

KubaParis

INHABITING basis

Location

basis e.V.Date

05.11 –27.02.2021Curator

Eike WalkenhorstPhotography

Katrin Binner, Copyright: basis e.V.Subheadline

During his residency at the Max-Planck-Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, Alexander Brix Tillegreen developed three bodies of works that reflect and relate to his work with sound illusions in different ways. He is connecting artistic with scientific approaches for his ongoing detailed research. Tillegreen made subjective listening and understanding within and outside borders of language the subject of discussion, while also questioning individual memory. Johanna Weiß talked to him about the unconscious, mental archives and his explorations at the seams between the sonic, the sculptural and the visual.Text

Johanna Weiß (JW): The exhibition “INHABITING basis” consists of three groups of works, divided into three spaces. A six-channel sound installation, a group of sculptural pieces and three graphic prints. In the first room your sound installation Phantom Streams (Zyklus I) is shown. It is opening up an acoustic space working with the phenomenon of the so-called Phantom Word Illusion. What does this phenomenon outline and what is your interest in it?

Alexander Brix Tillegreen (ABT): The sound composition is the reference point for the whole constellation of works. It is based on this psychoacoustic phenomenon called the Phantom Word Illusion, originally discovered by the music psychologist Diana Deutsch. This phenomenon is what I have been diving into developing both as an ongoing body of sound compositions but also interdisciplinary research in dialogue with scientists and staff at the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics. I work in very different media and this exhibition is an example of various types of work coming together, centered around the sound piece. The sound illusion evokes streams of words within the mind of the listener, which are not necessarily acoustically present. The words that are “heard” by the listener are based on their language background and subjective state of mind while listening. For example, a Chinese native speaker is more likely to hear rather Chinese words, and this goes, in theory, for all other languages. Therefore, the experience differs incredibly for every listener. Most people speak or understand bits of other languages than their mother tongue as well of course, which is also reflected in the experience.

Furthermore, the number of words the listener is hearing varies from each individual but also on their daily mindset. It seems like one person is more receptive to hear more words on one day and less the next day. In addition, visitors seem to hear words that are connected to recent events, experiences or memories. One listener for example, very clearly, heard the name of a recently lost lover. I am very interested in how this type of listening can unlock or mirror subconscious thoughts and feelings. In this way it is somehow reflecting the fluidity and plasticity of the mind.

Another important factor is the movement of the listener. The sound signals are getting mixed inside the room they are played in, so the combination of syllables changes on the way from the loudspeakers to the visitor’s ear. In a way, through movement, listeners are creating their own choreography of listening, composing their own experience. It's to some extent a participatory act of listening. I find it striking how one is confronted with one’s own “situatedness” - linguistically, psychologically and physically.

It is interesting to me how this material is able to somehow destabilize one’s relationship with reality through the illusory while listening. There’s a social aspect to it as well. It has a certain effect to listen to it in groups and talk about what is heard collectively. It's quite incredible how different the results can be.

Listening to the work also allows people to somehow play with and direct their own attention - and switch between streams of words and sentences they hear. I quite like that one can physically “hear” and thereby feel one’s own attention and play with it. Especially in a world today where attention is a resource that is constantly drained, exploited and hijacked by social media for example.

The perception of voice is also central to the piece. There is a psychoacoustic distortion of voice in listening to the work. I did a lot of research on voice, including an ongoing dialogue with a voice researcher. So, listening to the work, the “gender” of the voice can be flickering from male and female and in between. I find that also an interesting part of the piece - this blurry fluidity.

JW: In the next room the sculptural work Untitled (diffusers) is installed, which is partly based on the idea of a mental archive. Taking the idea further that subjective listening is based on memories and a vocabulary each person has stored in their consciousness and subconsciousness. The shown objects are usually used as acoustic diffusers in sound studios to reflect the sound in the space. They are taken out of context and shown as autonomous sculptures. In which way do these works refer to the idea of a mental archive?

ABT: That body of work is connecting to the sound piece in several ways and can be interpreted from different points of view. First of all, in a structural way, there is the similarity of rhythmic, repetitive blocks of serial sequences in variation. In a way they allude to each other’s formal structures. The sound and the sculpture group. I also think the modularity in them is important. I have earlier worked with the ‘Vierkantrohre Serie-D’ of Charlotte Posenenske in a slightly similar way in terms of juxtaposing a modular set of sculptural elements with a sound piece.

There are all these material threads and reference layers of correspondences in between. I think that the Phantom Word illusion and the sound work kind of activate and access the listener’s memory and vocabulary, so one could also see this group of sculptures as evoking imaginations of a mental archive. The shelf-like compartments and units could be reminiscent of storage facilities but then they also evade that with the different levels of depth. The sculptures also engage with movement, there is a play with shadow and light. The perception of this interplay changes perpetually when moving in front of them, due to the different depths of compartments in the objects. This aspect of movement is important in the psychoacoustic effects of the sound installation as well, where the listening experience is altered drastically by bodily movement.

JW: Your third body of work is a series of three graphic prints. How do they relate to the other works?

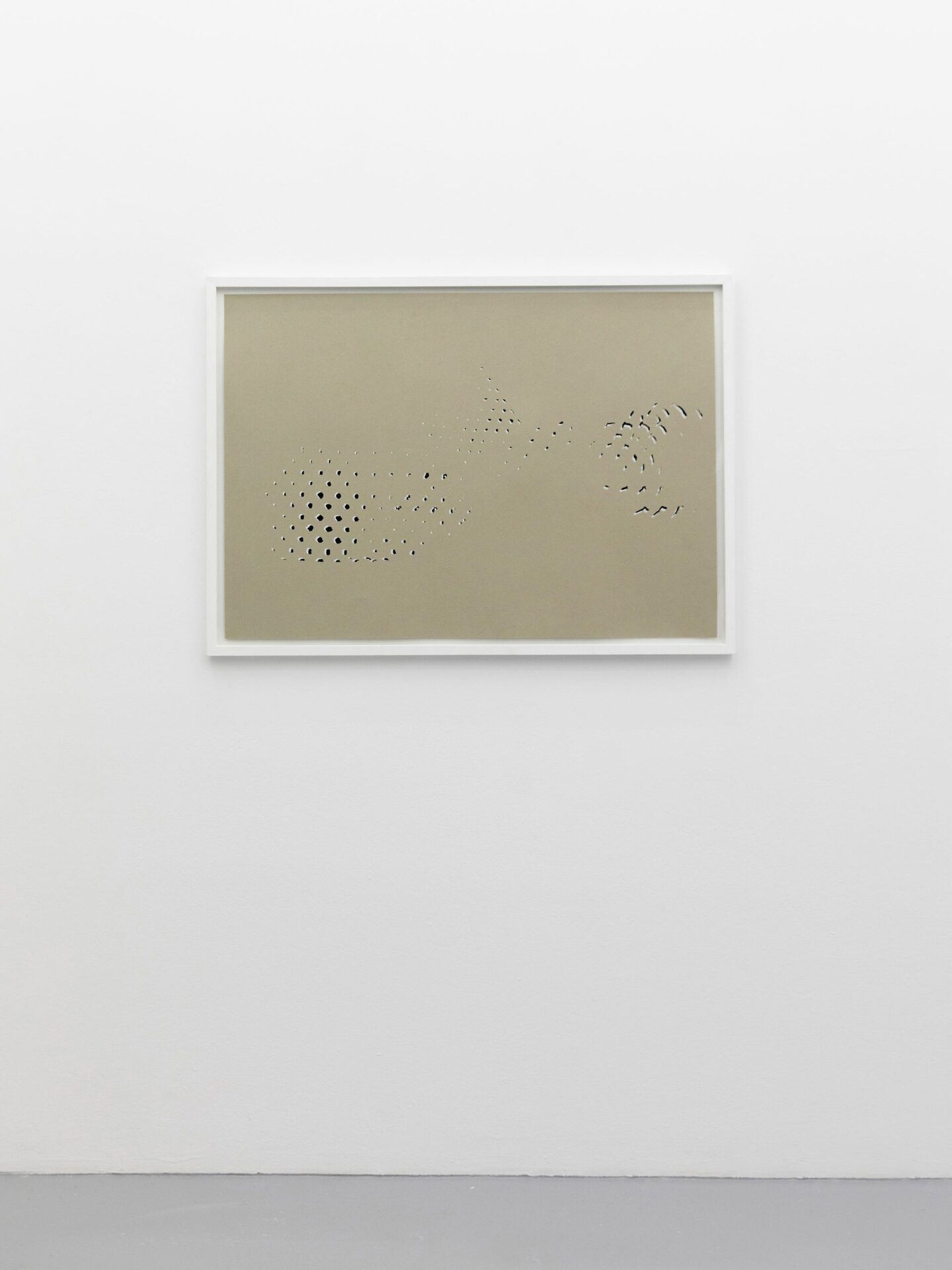

ABT: The silkscreen piece ,Score (5 movements)’ is a graphic representation of the compositional structure of the sound, much like in the sense composers have done earlier with visual, graphic scores. The two other prints are etchings and reflecting the psychological state of listening to the sound piece in more abstract ways. ‘Wanderer’ for example could be seen as a visualization of how it might feel to be surrounded and overwhelmed by shifting streams of sound, while ‘erwartung (feld)’ speaks about a sense of a semi-defined space and a sort of blurry field of voices.

JW: The exhibition is partly based on the Artist-in-Residence program INHABIT from the Max-Planck-Institute for Empirical Aesthetics and is one artistic materialization of your research during the residency. How have the interactions between you and the institute influenced the exhibition and your research?

ABT: About two years ago, before the program had started, I was already invited for a performance at the institute. At this point I started to engage with different scientists, including sound technicians, voice researchers and a neuroscientist who was also interested in the Phantom Word illusion. There was for example a lack of sound material of phantom word illusions that was based on the German language but also further technical things that I started to solve. At the performance I did later there was a psychology researcher who approached me and we started discussing a collaboration. Although we have different views and backgrounds we have a good collaboration going on and have some curiosity and questions towards the common material. These interactions with the institute unfolded to become the foundation of the program, the residency and the interdisciplinary work as it is now continuing.

I would say that there are indirect insights and dialogues that are equally important. I had many meetings and small experiments with linguists, musicologists, neuroscientists, sound technicians and a voice researcher. Dialogues and experiments brought me closer to the development of the material both knowledge-wise and artistically. There has been an ongoing reactive mode of experimentation and exploration at play. The most amazing thing for me, as the first fellow, has been to be able to consult people from such a broad range of fields at an interdisciplinary institute.

As mentioned before, one result of the residency is a concrete study about the Phantom Words phenomenon, that I designed together with a researcher from the Department of Language and Literature. I cannot share details or first results of the research at this moment since it is still running but I am looking forward to sharing it later. I can say that it is an actual laboratory experiment with more than 150 participants who engage in different ways with the sound material. For me, it is material research that is being conducted here as well as insights into the material and its various artistic and scientific aspects and effects on the human mind. These insights prompt also new ideas for further work and research. The research and the questions that the material raises are one thing. But I think the work itself has such a strong physical impact, everyone can understand it through the act of listening. One can see that in both the study and in artistic situations.

JW: What is the attraction of working in a scientific context for you?

ABT: I don't know if it has a direct attraction, or it is not consciously planned out. It is more something that is happening organically. It started very naturally somehow, and I always had interests in different disciplines. I think art can incorporate things from many areas of knowledge. At the same time, artistic material and methods can exist in and contribute to scientific contexts and operate in meaningful ways. This can tap back into the artwork. In general, I think that there is great and beautiful potential in working interdisciplinary. It can be challenging sometimes especially when overcoming communication problems. But I really think it can be worth it and it can be productive for several parties although it also doesn’t have to be productive in a measurable sense. Personally, I have been very satisfied and grateful for the openness I have been met with at the institute from all departments. I think if you come with a certain energy, you will be met with something similar. I can function and move around in different ways and contexts within and outside of the “arts” or “science” and bring things between disparate fields. We participated for example in a festival where we did a small experiment that then became a “pre-study” for our actual experiment. We could simply use this data to outline and raise the support within the institute to establish and design the bigger study.

As an artist moving in and out of certain contextual spheres - which is one of the “powers” we have – we might be at times, also within the art world, confronted with pigeonholing and met with rigid expectations.

I have my whole life been strongly opposed to pigeonholing. One has to always fight for freedom and mobility if one wants that. I am against restrictive, narrow-minded understandings of what an artist or knowledge exchange can be. Instead, responsiveness and acknowledgment of nuances and fluidity are rather important. I think art can play a key role in that on a societal level.

JW: How do you see the relationship between artistic research and your artistic practice?

ABT: The term artistic research is a complicated term; it is widely discussed and rightly so. It is hard to generalize, and I feel like many projects are so beautiful in their specificity. In a way I believe all artists do what one could call artistic research. But operating temporarily as an artist in a scientific environment, subtracting and exchanging knowledge, exploring different interdisciplinary potentials and aspects of a material is a very specific mode of working. In my case I feel that these moments of research and the practice is overlapping. Knowledge influences the formations that take place, and this partly shapes the work. Experimentation happens in a constant, reactive way and this is just one out of many modes of working for me. I also believe that many things can form the creation of a work. Including atmospheric conditions like the weather.

JW: Which opportunities do you see in the collaboration between artists and scientists? What will remain for you from this collaboration?

ABT: I would be very careful saying anything generalized about both parties. One could say that both scientists and artists are driven by a genuine curiosity about the world and more or less systematic experimentation towards questioning things and working with material.

I think that a big potential lies in dialogues between people and disciplines. It is important to be able to step out of one’s own situated knowledge field and feel stupid for a while and be open to examine and listen to other disciplines. One’s intuition and being in sensible contact with it is something artists are very good at (some scientists too!). We are sometimes able to see connections between things that are often overlooked, and we can get very involved with a material, and share our insights on several levels. This can be useful in terms of what artistic research could be.

There are many things remaining for me from the collaborations and they are still ongoing. New ideas, questions and dialogues keep popping up around this material and there is still the study to finish as well. One of the things I like about working with sound and specifically this body of work is that it can adapt and unfold into different formats where it can live and act in various ways. For example, I am working on a solo album where I will include parts of the sound work. Then there are listening sessions coming up that take on more participatory and performative modes of presentation and experience. I am also working on a museum exhibition where the site-sensitive activation of the architecture and choreography of space is animated again by the means of sound installation. Research wise I am also working on different textual outcomes and future studies.

About the program:

The exhibition INHABITING basis is the first collaboration between basis e.V. and the Max-Planck-Institute for Empirical Aesthetics. The starting point is the Artist-in-Residence program INHABIT which was founded at the Max-Planck-Institute in Frankfurt in 2019. Within this framework, three guest artists from different artistic disciplines worked in dialogue and exchange with scientists from the research institute for three months each year. The joint exhibition at basis e.V. features the artists of the first edition of INHABIT – Lea Letzel, Pedro Oliveira, and Alexander Tillegreen – and the works they created during their residencies. All three artistic positions deal with the topic of sound in terms of content and concept but take very different forms. Their works manifest different approaches to the scientific environment and aesthetic practices informed by the specific encounter, dialogue, and cooperation during their fellowship.

The exhibition, which was supposed to be open on November 6, 2020 and run until February 14, 2021 could not be shown to the public due to the current Covid-19 measurements.

Curator of the Artist-in-Residence program & exhibition: Eike Walkenhorst