Archive

null

KubaParis

LA LA CUNT

Location

Dortmunder KunstvereinPhotography

Simon Vogel, Dortmunder Kunstverein, 2020Subheadline

LA LA CUNT – Anne-Lise Coste / Review von Muriel MeyerText

Ich verbringe meine Quarantäne in LA LA CUNT. Die Wörter und Bilder innerhalb des Ausstellungsraumes wechseln ihre Bedeutung je länger die Rezeptionszeit andauert. Am 21. Februar 2020 eröffnet die Ausstellung LA LA CUNT von Anne-Lise Coste im Dortmunder Kunstverein, kuratiert von Oriane Durand. Beinahe einen Monat zuvor hat das Coronavirus bereits Deutschland erreicht. Ein Mann aus dem Landkreis Starnberg in Bayern ist infiziert. Die Chronik einer Pandemie und mein Ausstellungsbesuch beginnen. Die Grundrisse unserer Wohnungen und Häuser gewinnen während der Zeit der sozialen Distanzierung und der Quarantäne an Bedeutung. Die berüchtigte U-Form des Dortmunder Kunstvereins zwingt mich, die Arbeiten sequentiell zu betrachten. Die beiden Seitenflügel spiegeln sich architektonisch. Die Querseite verbindet die Trakte räumlich. Der Grundriss erlaubt durch seine spartanischen Innenwände einen offenen Spaziergang hin und zurück, jedoch keinen Rundgang. Die verglasten Außenseiten des U-s gewähren den größtmöglichen Kontakt zum Außenraum und vice versa. Der Eingang befindet sich im linken Flügel. Knapp einem Monat nach dem LA LA CUNT eröffnet ist, schließt die Ausstellung unerwartet für acht Wochen.

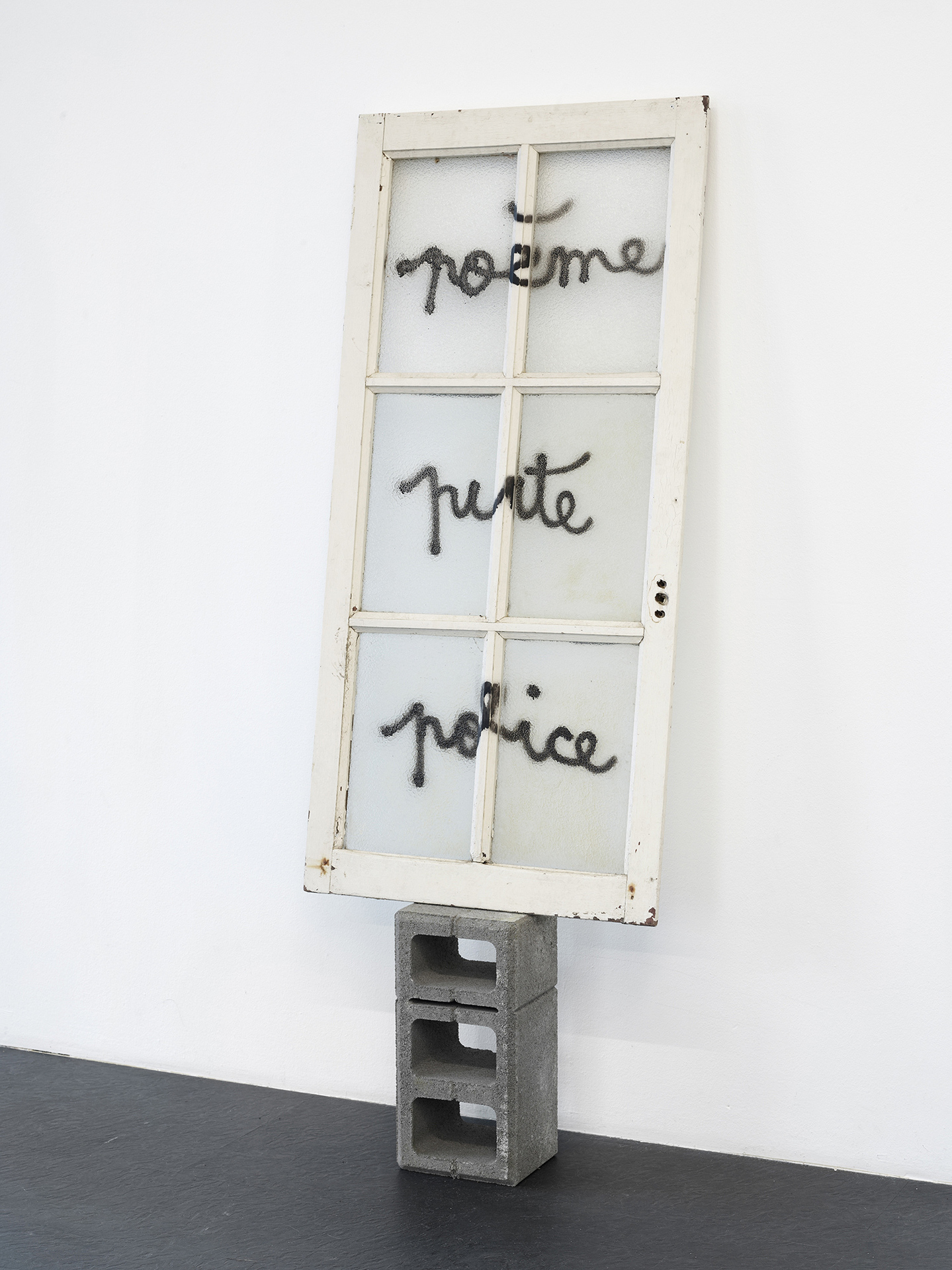

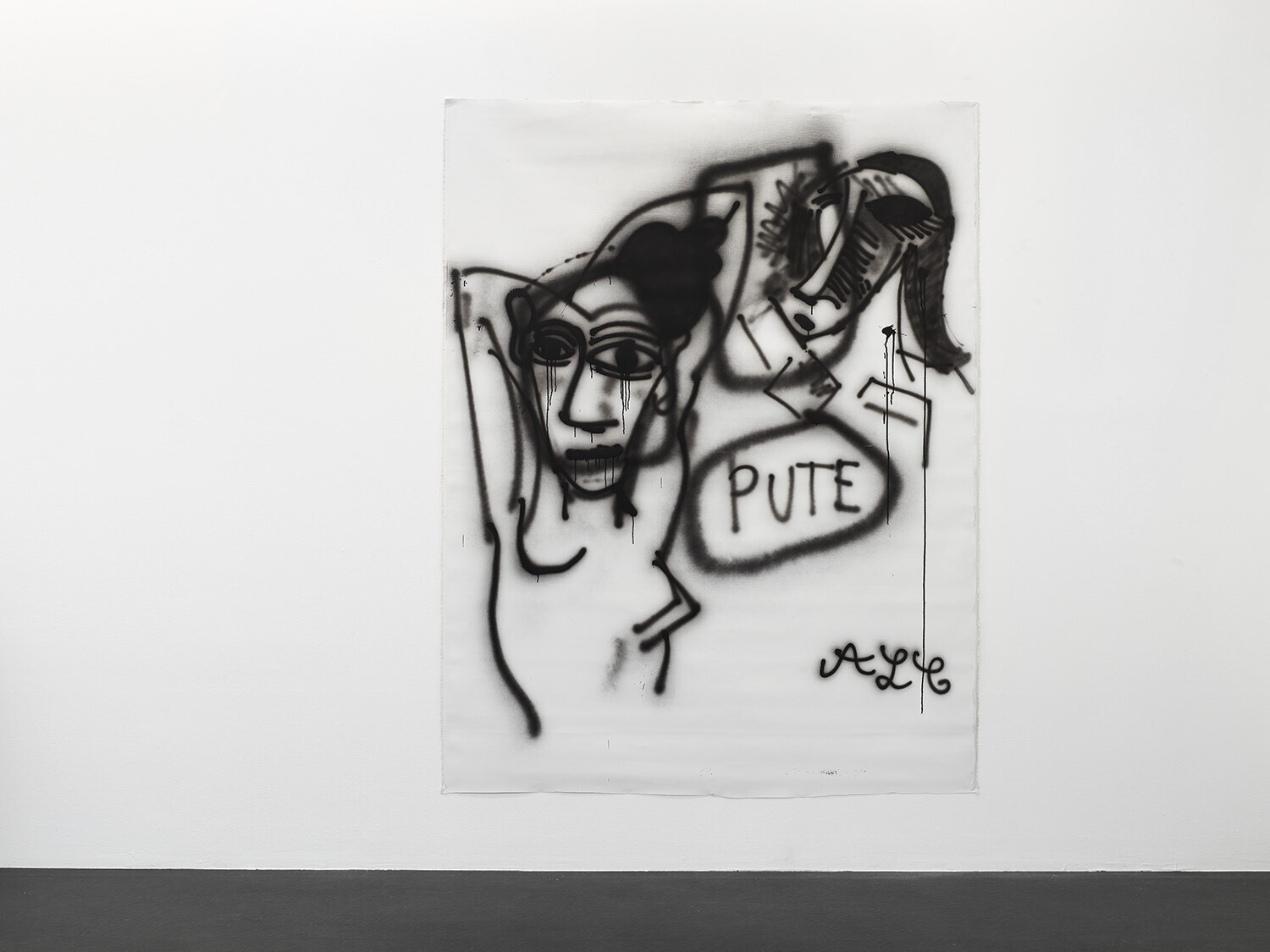

Direkt neben der Glastür steht die erste Arbeit: Poème, Pute, Police (2020). Das Licht der umgebenden Fensterfront verfängt sich im Milchglas des sechsteiligen Fensters der Arbeit. Der Blick aus dem Fenster als die minimalste tägliche Interaktion mit der Außenwelt hat während der Quarantäne das Leben vieler Menschen weltweit gerettet. Der einzige Ausblick in der Isolation auf das Außen, das weder imaginiert oder digital vermittelt ist, bringt mich zum neuralgischen Punkt: Kunst und ihr Verhältnis zur Wirklichkeit. Bereits René Magritte hat in seinen Arbeiten damit Schabernack getrieben – darunter zahlreiche gemalte Fenster. Das Kunstwerk Poème, Pute, Police zeigt eine Perspektive auf die Realität, genauso wie ein Blick aus dem Fenster. Unsere Sicht auf die Welt gleicht dem Blick durch ein Guckloch, niemals sehen wir das komplette Bild. Das Kontaktverbot hinterlässt seine Spuren. Die Kunst umhüllt mich und an manchen Tagen schaue ich die Arbeiten an, als ob ich sie zum ersten Mal sähe bzw. sie mich. Ich meine Marcel Duchamps Fensterskulptur Fresh Widow (1920) in Anne-Lise Costes Arbeit zu erkennen. Die Unterschiede zwischen seinem Fenster, das er bei einem Handwerker in Auftrag gegeben hat, einem Ready-Made und dem Objet trouvé von Coste interessieren mich nicht. Was mich fesselt ist die Krisenhaftigkeit der beiden Arbeiten: Das Milchglas und die Polizei, das bezogene Leder und die Nachkriegszeit. Das Wortspiel Fresh Widow zwischen dem französischen Fenster und der Witwe eines verstorbenen Soldaten hat etwas Obszönes. Eine Frau mit einem Objekt gleichzusetzen, ist eine chauvinistische Sauerei, genauso wie einer Witwe etwas Frevelhaftes anzuhängen. Zurück zu den gesprayten Wörter Poème, Pute, Police auf den einzelnen Scheiben vor mir. Klar ist die Verbindung mit der Malerei PUTE (2020) auf der gespiegelten U-Seite. Doch die Tage verschwimmen zu einer Brühe. Die Kunstwerke um mich herum vermischen sich zu einer unheimlichen Gemengelage. Auf der anderen Seite zeigt die Airbrush-Malerei PUTE einen Ausschnitt von PicassosDemoiselle d’Avignon (1907), die Ikone des größten Chauvinisten der Klassischen Moderne: Warum bezeichnet Picasso die Frauen auf seinem Gemälde als Fräuleins anstatt als Sexarbeiterinnen?

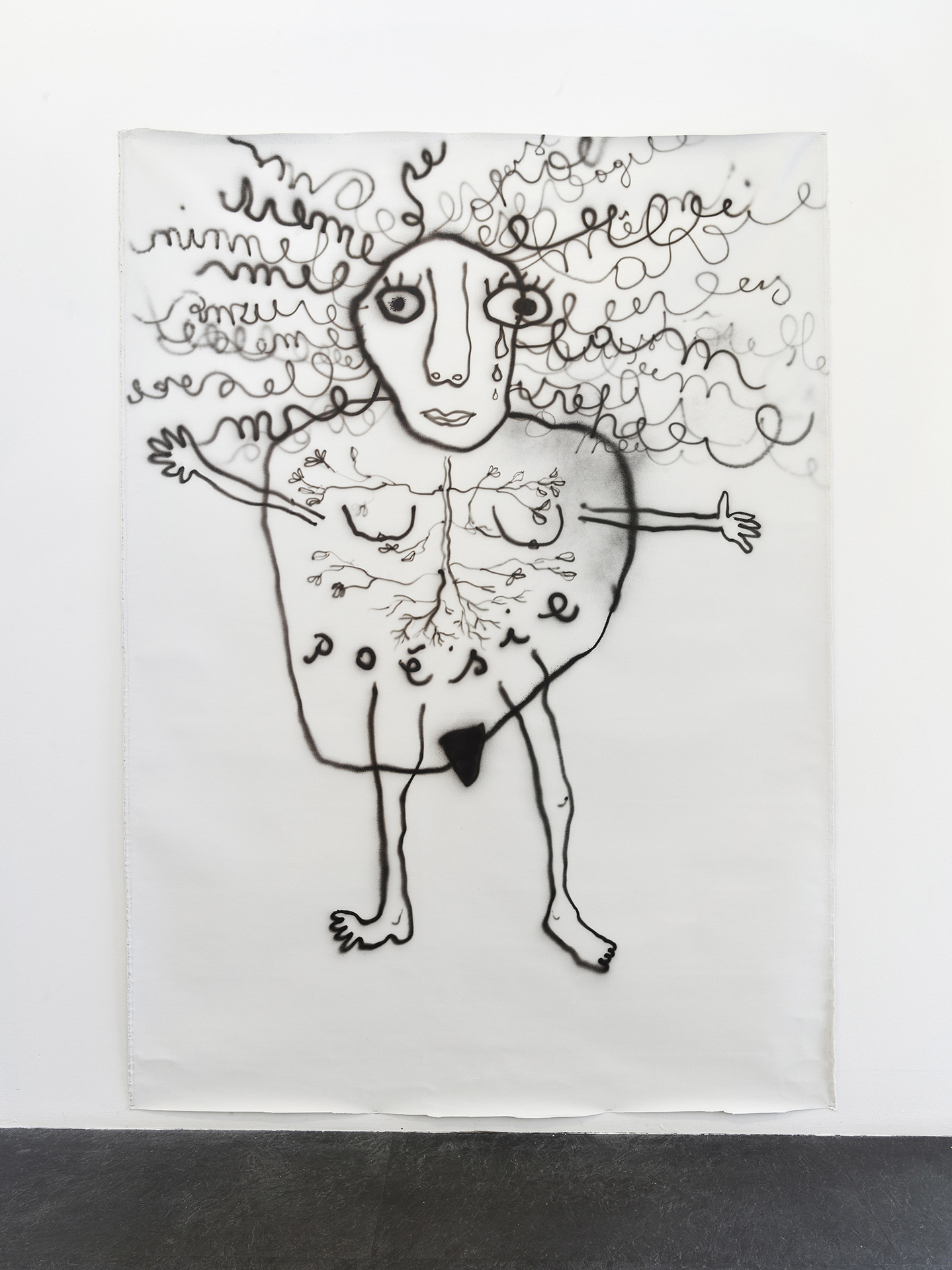

Je länger die Quarantäne andauert, umso mehr sich um mich herum, außerhalb des Ausstellungsraums das Virus ausbreitet, suche ich Ausflüchte. Ich erweitere meinen Bewegungsradius. Um mich abzulenken, betrete ich hinter dem Eingang den einzigen etwas abgetrennten Raum der U-Form. Am Boden liegt ein weiterer Geist der Kunstgeschichte. In Glühbirnenform erscheint vor mir Félix González-Torres. Er hat seine Arbeiten seinem an AIDS verstorbenen Lebenspartner Ross gewidmet. Meine über die Krise hochgezüchtete Melancholie steigt in mir auf: Wer jetzt alleine ist, wird für immer alleine sein! González-Torres thematisiert den Verlust eines geliebten Menschen in einer Pandemie, die – tabuisiert –viel zu lange nicht als solche behandelt wurde. Meine wirre Gedankenwelt sucht nach Parallelen zwischen der Pandemie des 20. und der des 21. Jahrhundert. Mir fällt keine ein, außer, dass wir von der ACT-UP Bewegung lernen können, der es gelungen ist, aus der Perspektive von Minderheiten, die Welt zu verändern. Zur Arbeit Poésie (2020)gehört nicht nur die Glühbirne am Boden, sondern auch eine lose Leinwand, lässig an die Wand getackert: Einem Wesen zwischen Weiblichkeit und Non-Binärität entweicht eine Träne. Eine riesige Lunge durchwächst diesen Körper. Unsere Sauerstoffversorgung ist durch das Virus bedroht. Die Lunge als Baum spiegelt unsere Lebensader. Die Erdatmosphäre ist verschmutzt, die Meere sind zu heiß und der Regenwald wird trotz Covid 19 abgeholzt. Der Mensch stört empfindlich. Ich atme ein, ich atme aus.

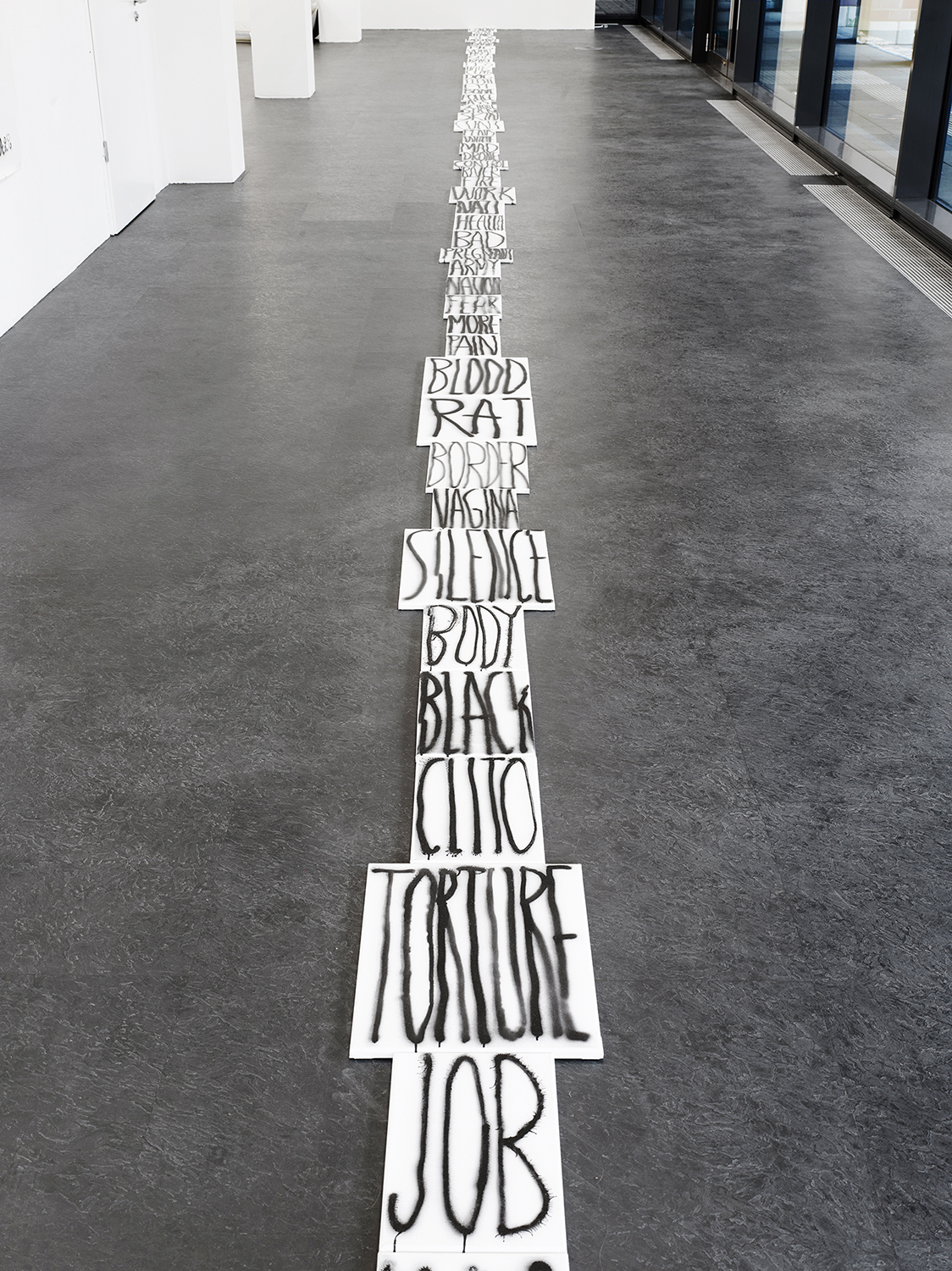

Auf Malereien, leeren Leinwänden, Objekten, an der Wand oder am Boden verteilt, überall in der Ausstellung stehen Wörter und formieren sich. Am eindrücklichsten geschieht dies in der Arbeit: Poème de la Douleur (Poem of Pain)(2020). 56 gerahmte Leinwände auf denen jeweils ein Wort gesprayt ist. Sie liegen auf dem Boden und durchziehen den Querraum des U-s. Sie verbinden ebenso die Arbeiten, wie sie den Raum durchtrennen: BAD HEALTH NAZI WORK FIRE RIVER CONROL DRONE MAD WHITE PENIS. Die Wörter erinnern mich daran, dass meine Quarantäne bald vorbei ist. Sie hämmern und klopfen. Ich will nicht wieder raus in die Welt, die aus diesen Wörtern besteht. Marcel Broodthaers Rauminstallation La Salle Blanche (1968) ist ein geistiger Rastplatz, um noch ein wenig in der geschützten Blase der Ausstellung zu verweilen. Das harte Schwarz auf Weiß trifft mich in beiden Arbeiten, die getaggten Druck- und Kapitalbuchstaben von Coste schreien mich an, während mich die sanfte Schreibschrift Broodthaers nostalgisch stimmt. Sie alle bezeichnen Begriffe aus der Kunstszene, wie fenêtre (Fenster), galerie (Galerie), amateur (Amateur), pourcentage (Prozentsatz), collectionneur (Sammler*in) und nuage (Wolke). Broodthaers hat eine Sperrholznachbildung seines Schlafzimmers mit den Kunstbegriffen versehen: Privates und Berufliches hat sich in der Kunstwelt längst vor dem verordeneten Homeoffice vermischt. GUN BOMB PIG VOMIT MASK – die Außenwelt meldet sich unangenehm. AIR SHIT VISA WHO JOB TORTURE CLITO BLACK BODY SILENCE VAGINA BORDER RAT – die Wörter rufen mich auf die Straße. Ich muss raus aus den Räumen, die Ausstellung hat schon längst geschlossen. Mein Text erscheint verspätet mit einem Gruß aus der endlich beendeten Quarantäne.

______

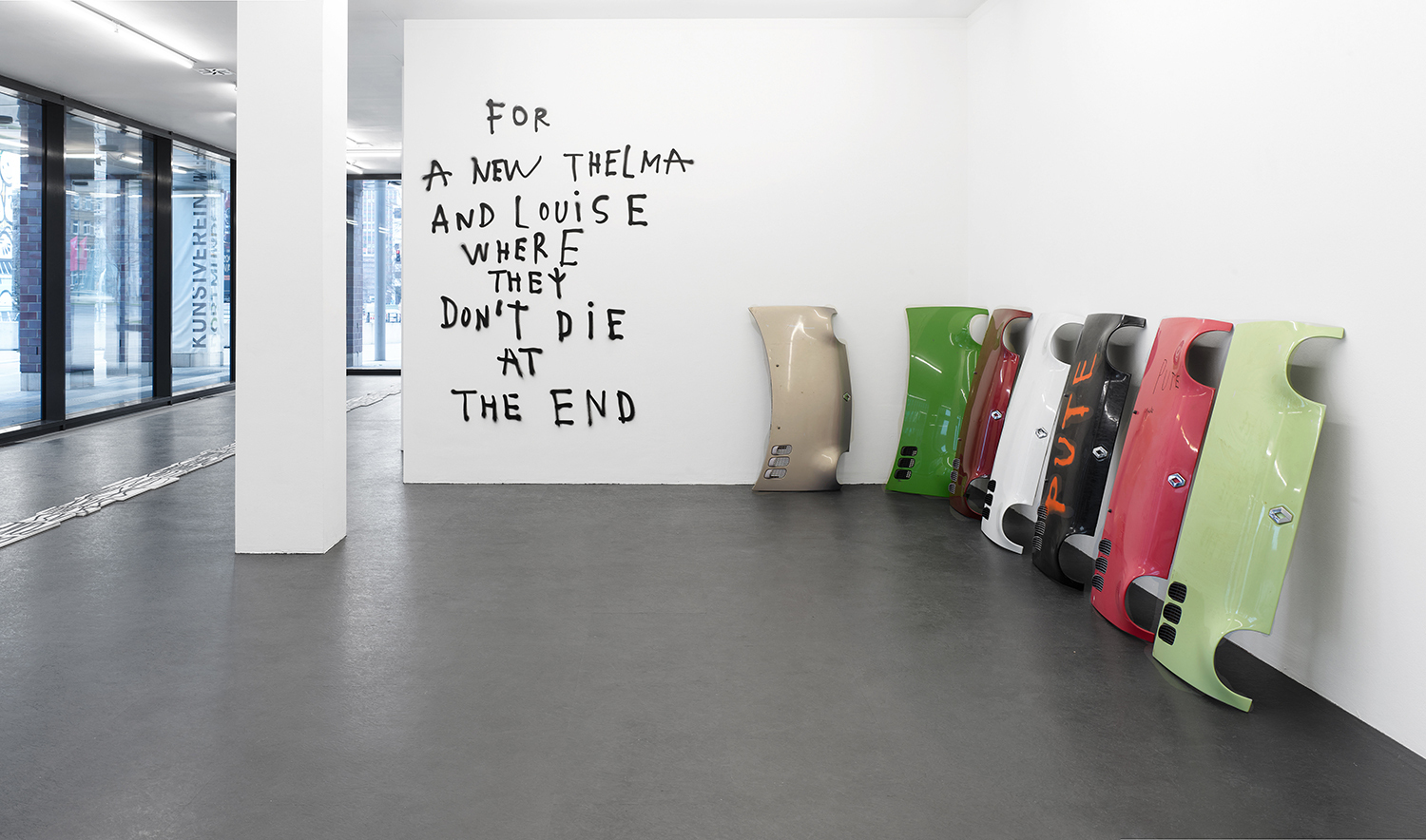

I spend my quarantine in LA LA CUNT. The words and images within the exhibition space change their meaning the longer the time of reception takes. On February 21, 2020, the exhibition LA LA CUNT by Anne-Lise Coste, curated by Oriane Durand, opens at the Dortmunder Kunstverein. The Coronavirus has already reached Germany, seeing its first case nearly a month previously when a man from the Bavarian county of Starnberg is infected. The chronicle of a pandemic and my exhibition visit begin. The layouts of our apartments and houses gain greater significance during the time of social distancing and quarantine. The signature U-shape of the Dortmunder Kunstverein forces me to view the works in sequence. The architecture results in two mirroring side wings connected spatially via a transversing side. The floorplan’s spartan interior walls allow for an open walk back and forth, but not for a full circuit through the space. The glazed exterior walls of the U afford the greatest possible contact with the outside space, and vice-versa. The entrance is located in the left wing. Less than a month after the exhibition’s opening, LA LA CUNT closes unexpectedly for eight weeks.

Directly next to the front door stands the first work: Poème, Pute, Police (2020); the light of the Kunstverein’s window front is caught in the frosted glass of the work’s six-paned window. The view outside the window, as the most minimal of daily interactions with the outside world, has come to save the lives of many people worldwide during quarantine. Within isolation, this singular view towards the outside – neither imagined nor digitally mediated – brings me to the neuralgic point: art and its relation to reality. René Magritte has notoriously toyed with this in his works – amongst them, many painted windows. Coste’s artwork Poème, Pute, Police reveals a perspective on reality, and at the same time, a view outside the window. Our view of the world is like looking through a peephole: we never see the complete picture. Social distancing leaves its traces. The art envelops me, and on some days I look at the works as if it’s the first time I see them, or rather, that they see me. Anne-Lise Coste’s work somehow reminds me of Marcel Duchamp’s window-sculpture Fresh Widow (1920). I’m not particularly interested in the differences between his window (which he had commissioned from a craftsman), a readymade, and Coste’s objet-trouvé. What captivates me is the sense of precarity in both of the works: the frosted glass and the police; the upholstered leather and the post-war period. The play on words in “Fresh Widow,” between the French window and the widow of a deceased soldier, has something obscene about it. To equate a woman with an object is grossly chauvinistic, just as it is to ascribe something wantonly frivolous to a widow. But back to the words Poème, Pute, Police spray-painted on the individual panes in front of me. The connection to the painting PUTE (2020) on the mirroring side of the U is obvious. But the days blur indistinctly; the artworks surrounding me blend into an uncanny mishmash. On the other side, the airbrushed painting PUTE shows a detail of the Demoiselles D’Avignon (1907), the icon of Classic Modernism’s greatest chauvinist: Why does Picasso refer to the women in his painting as “Demoiselles” – unwed women – rather than as sex workers?

As the quarantine continues, and the more the virus spreads surrounding me outside of the exhibition space, I look for escape. I expand the radius of my movements. In order to distract myself, I step into a room tucked behind the entrance – the only room somewhat removed from the U-shape. On the floor lies another spirit of art history. Félix González-Torresappears before me in the form of a light bulb. He dedicated his works to his partner Ross, who died of AIDS. The melancholy I have cultivated over the course of the crisis arises in me. Whoever is alone now will remain alone forever! González-Torres dealt with the loss of a loved one during a pandemic that, being taboo, for far too long was not treated as such. My confused realm of thoughts looks for parallels between these pandemics of the 20th and 21st centuries. I can think of none, other than that we can learn from the ACT-UP movement, which succeeded in changing the world in regard to the perspective of minorities. The work Poésie (2020) includes not only the light bulb on the floor, but also a loose canvas nonchalantly stapled to the wall: a figure imaged somewhere in between femininity and non-binariness releases a tear. An enormous lung grows through this body. The virus threatens our oxygen supply. The lung as a tree reflects our lifeline. The earth’s atmosphere is polluted, the oceans are too hot, and despite COVID-19, the rainforests are still being chopped down. Humankind palpably threatens. I breathe in; I breathe out.

Words are everywhere – on paintings, on empty canvases, on objects scattered across the wall or floor – converging into constellations throughout the exhibition. Perhaps the most impressive example can be viewed within the work Poème de la Douleur (Poem of Pain) (2020): 56 framed canvases, each bearing one spray-painted word. They lie on the floor and span the transverse arm of the U. They connect the works as they cut through the space: BAD HEALTH NAZI WORK FIRE RIVER CONTROL DRONE MAD WHITE PENIS. The words remind me that my quarantine will soon be over. They hammer and knock. I don’t want to go back out into the world composed of these words. Marcel Broodthaers’ installation La Salle Blanche (1968) is a mental resting place, allowing me to remain a bit longer within the protected bubble of the exhibition. The stark black-on-white of both artists’ works strikes me: Coste’s tags in all-caps scream at me, while Broodthaers’ soft script makes me feel nostalgic. The words in La Salle Blanche all refer to art-world terms: fenêtre (window), galerie (gallery), amateur (amateur), pourcentage (percentage), collectionneur (collector), and nuage (cloud). The art terms adorn a plywood replica of Broodthaers’ bedroom: within the artworld, the private and the professional have been enmeshed for a long time, long before the prescribed home office. GUN BOMB PIG VOMIT MASK – the outside world beckons uncomfortably – AIR SHIT VISA WHO JOB TORTURE CLITO BLACK BODY SILENCE VAGINA BORDER RAT. The words call me out to the street. I must leave these rooms; the exhibition has long since closed. My text appears belatedly with a greeting from the quarantine, which has finally ended.

Muriel Meyer