Archive

2022

KubaParis

Le Métier de Vivre

Location

Beaux-Arts de ParisDate

22.03 –29.04.2022Curator

Raphael GiannesiniPhotography

Laurent GiannesiniSubheadline

Pascal Aumaitre, Ludovic Beillard, Marion Chaillou, Xolo Cuintle, Ann Daroch, John Henry Dearle, Francisco G Pinzón Samper, Ninon Hivert, Maître de Jacques de Besançon, Maëlle Lucas-Le Garrec, Matteo Magnant, William Morris, Kiek Nieuwint, Eliott Paquet, Charlotte Simonnet, Raphael Sitbon, William Arthur Smith Benson, Luca Resta, Constantin Von Rosenschild, Philip Webb. Through one’s profession – métier – one specifies oneself through forms and determines one’s existence. Affected by historical and economic constraints, a trade is as much about the practice of a skill as it is about the expression of a need. But what about artists who have made it their profession to create, use their creations as “tools” to live ? Where do artists fit in as both artisans and inhabitants of a world that they contribute to shape by what they make and how they live ? Bringing together several generations of makers whose dialo- gues span the ages, the exhibition explores the proximity between art and applied disciplines. Far from an autarkic vision, the “métier de vivre” thus explores the idea of broadening artistic activity so that it encompasses de-compartmentalized and collective modes of production, with the aim to revive exchanges between work and object, art and life. In order to explore the nature of creations and creators, and to question the ambiguous relationship they may have with the work at hand and its use, the exhibition, following the tradition of medieval “multi-purpose houses”, is organised in a space that is both a workshop and a home. This two-entrance space invites teachers, students, illuminators, artists, embroiderers, designers and carpenters to participate in the writing of a history in which trades, objects and beings merge beyond their finalities to explore a new way of thinking and making forms.Text

Through one’s profession – métier – one specifies oneself through forms

and determines one’s existence. Affected by historical and economic

constraints, a trade is as much about the practice of a skill as it is

about the expression of a need. But what about artists who have made

it their profession to create, use their creations as “tools” to live ? Where

do artists fit in as both artisans and inhabitants of a world that they

contribute to shape by what they make and how they live ?

Bringing together several generations of makers whose dialo-

gues span the ages, the exhibition explores the proximity between art

and applied disciplines. Far from an autarkic vision, the “métier de

vivre” thus explores the idea of broadening artistic activity so that it

encompasses de-compartmentalized and collective modes of production,

with the aim to revive exchanges between work and object, art and life.

In order to explore the nature of creations and creators, and

to question the ambiguous relationship they may have with the work

at hand and its use, the exhibition, following the tradition of medieval

“multi-purpose houses”, is organised in a space that is both a workshop

and a home.

This two-entrance space invites teachers, students, illuminators,

artists, embroiderers, designers and carpenters to participate in the

writing of a history in which trades, objects and beings merge beyond

their finalities to explore a new way of thinking and making forms.

The illuminator and the guild

Certain objects in the Beaux-Arts collection, some almost a thousand

years old, hark back to times when a different history of creation pre-

vailed. The Books of Hours, which structured the day for laypeople

through a set of prayers to be performed daily, are the embodiment of a

medieval society controlled by religion. These everyday objects describe

a period when art still conformed to the laws of custom, and artists

were considered craftsmen. Monastic guilds, thriving in anonymity,

articulated patterns and repetitions to put in writing the life of a man,

Christ, whose asceticism and modesty stood as exemplary. From the

parchment maker to the copyist, from the scribe to the illuminator, the

books passed from hand to hand, from expertise to expertise, crafted

by both the specific genius and collective engineering of these workers

of God. In the age of Gothic, which was as much a style as a system,

these craftsmen, breviary illuminators, image carvers and cathedral

builders merged with their works, only to disappear behind them.

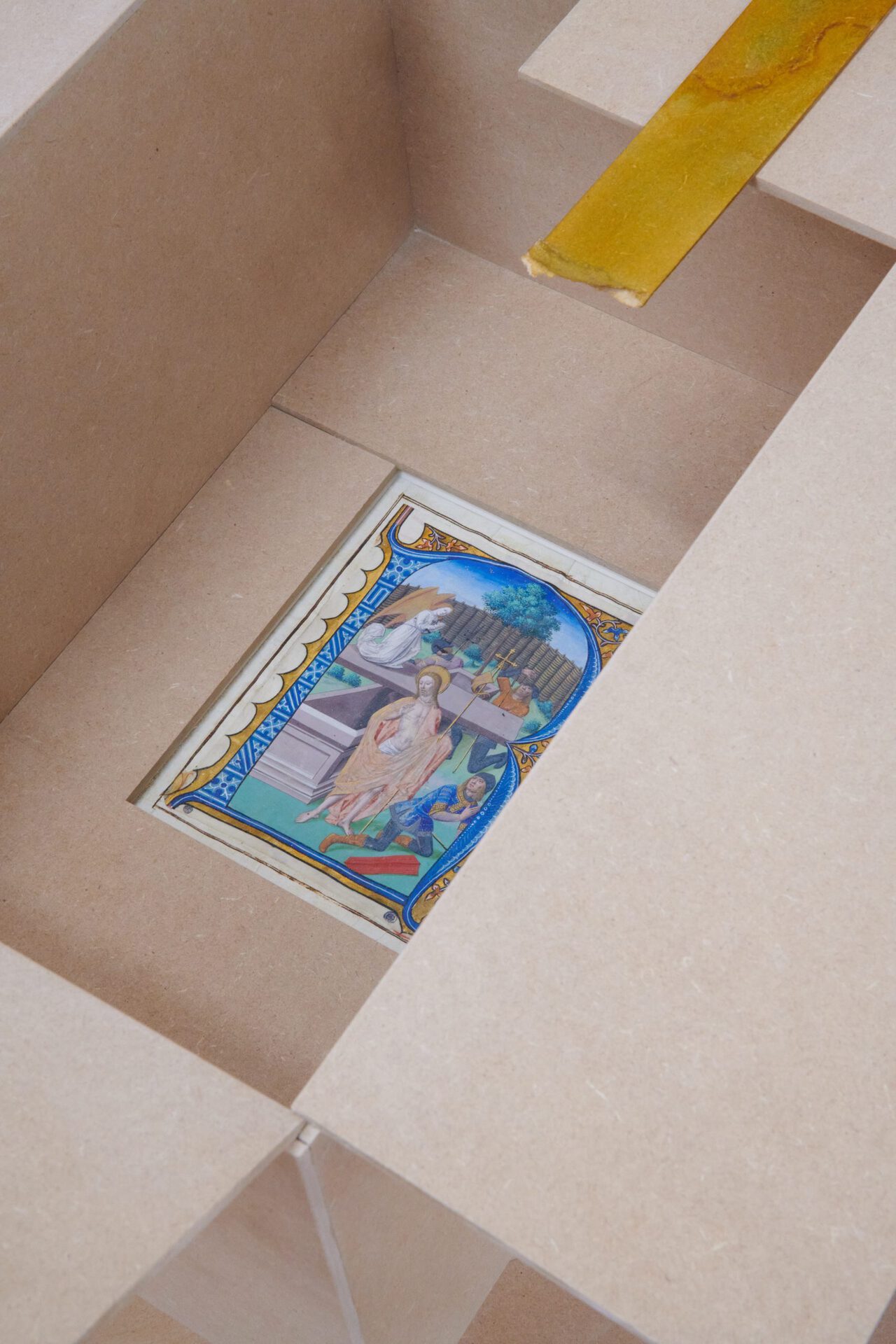

From the Beaux Arts collection, vairous codex fragments dating

from the 15th century are nestled on the exhibition walls. Presenting tra-

ditional religious scenes, and illustrating the content of future prayers,

these pages are the work of a master illuminator whose name, Jacques

de Besançon, was given to him by history. Here, the artist Raphael

Sitbon has imagined a system of nested box-like structures that house

these precious works ; the horizontal and collective production processes

are, then and now, a model for a possible coming together of the arts.

The decorator and the company

In the 19th century, in an insular and Victorian England, a system called

capitalism was developed that imposed its law and creed : progress.

In contrast to this belief in machines and industry, the poet, painter

and architect William Morris initiated an artistic revolution: the Arts

& Crafts movement. Influenced by Marxist ideas and nostalgia for the

Gothic, he conceived new design and production paradigms.

The Decorative Arts became for him the medium through

which he pursued this political and aesthetic commitment to reintro-

duce pleasure into work and beauty into life. In response to a liberal and

competitive system, he recreated a corporation of craftsmen: Morris &

Co. At a time when tools were becoming mechanised and objects indus-

trialised, members of his firm were trained in traditional crafts such as

tapestry, embroidery, coppersmithing, marquetry and cabinetmaking.

In the same way, ornamentation and decorative patterns, inspired by

medieval interlaced designs, also become a means for Morris to counter

the standardisation of forms.

On loan from the Oscar Graf Gallery, three artefacts from

the Morris & Co. workshops can be seen in the domestic section of the

exhibition. A floral embroidery by Ann Daroch, based on a design by

William Morris, is displayed alongside a rosewood shelf designed by

Philippe Webb, the father of Arts & Crafts architecture. A sconce by

the designer William Arthur Smith Benson completes this selection of

objects that testify to a poignant union between production and design,

art and utility.

Artists and artisans

Late capitalism, characterised by the development of automation,

virtual worlds and artificial intelligence, raises further questions about

the shapes to come. The possible disappearance of work, the eclipsing

of objects and the rise of social solitude call for a renewed appreciation

of work as a means of sharing and finding happiness. In the wake of

this movement, the contemporary artists invited to participate in this

exhibition are firmly rooted, contrary to our past century’s conceptual

movements, in a newfound materiality, and sometimes even in the

idea of “making” as an end in itself. The poetic art of «making» has

gained renewed interest. Technique, which has often been dismissed

as secondary to concept, is regaining its power as a source of control

and freedom for artists. The expressiveness of manmade, handcrafted

objects is being rediscovered. As these artists learn from history and ac-

quire specific skills, they are able to resume a form of dialogue with past

makers. From illuminators to set designers, they follow in the footsteps

of men and women whose styles and practices constitute the formal

and conceptual resources that enable the invention of new narratives.

The project includes not only a series of works by artists who

are either graduates of the Beaux-Arts de Paris or people from outside

the school, but also several functional sculptures resulting from a col-

laboration with the École’s wood workshop (la base bois). Pursuing

a horizontal approach similar to the one adopted by William Morris

and past illuminators, supervisors, students and professors have wor-

ked on the construction of collective forms conceived as spaces where

dialogue can take place. In this system, pieces of furniture, sculptures

and structures blend together much in the same way as their authors.

A wall becomes a series of cabinets, a chair a stand, a table a chest of

drawers. The subversion of values and functions follows the logic of a

multi-purpose space that transitions from productive space to domestic

space. This theatre of objects, brought to life through the interplay of

construction, organisation and furnishing, creates a stage where the

actors of forms perform collectively a trade... The trade of living.