Archive

2022

KubaParis

L'Évidence éternelle

Location

DépendanceDate

14.01 –25.02.2022Curator

Louis-Philippe Van EeckhouttePhotography

Alice Pallot (except for reproductions of Linder: Kristien Daem)Subheadline

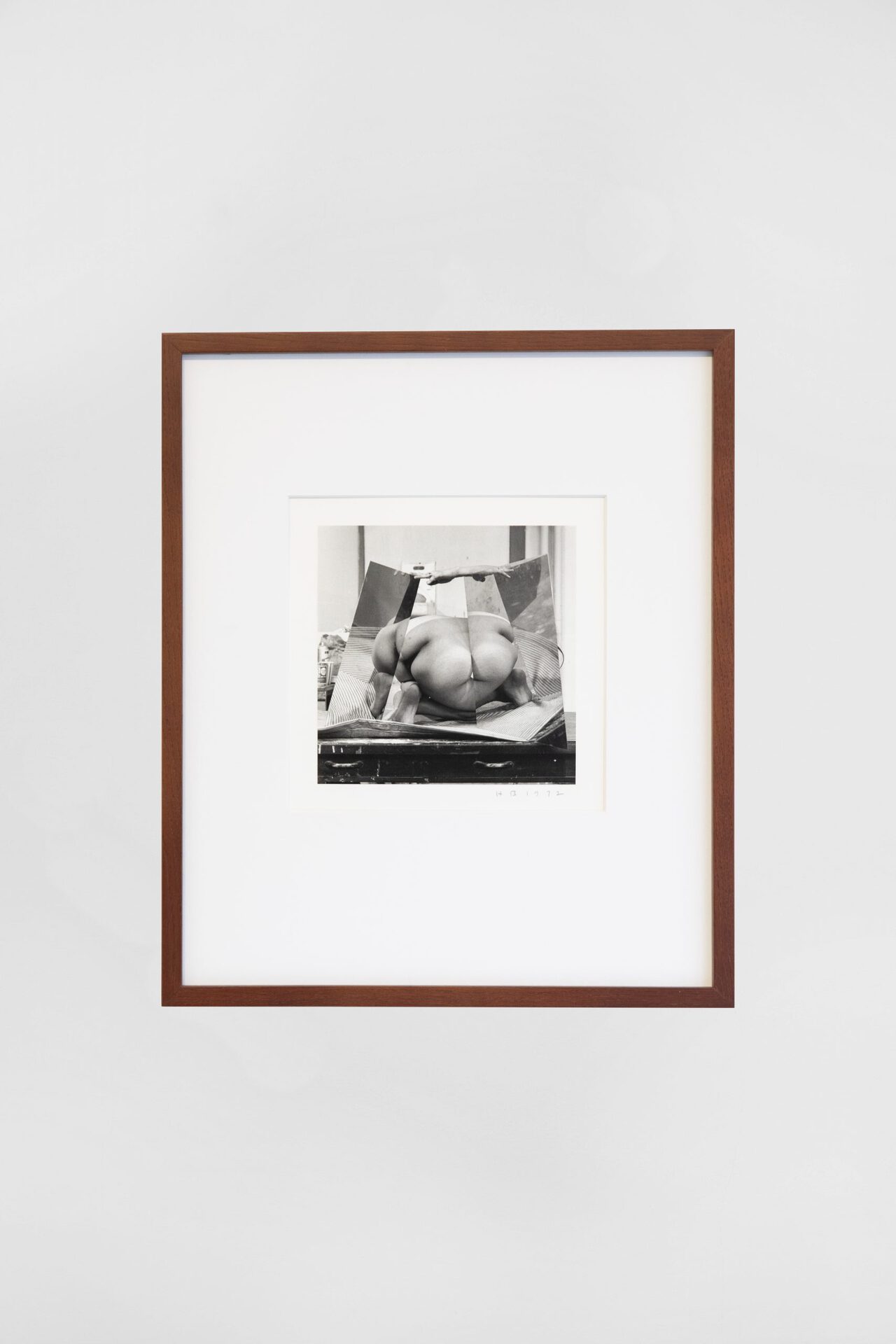

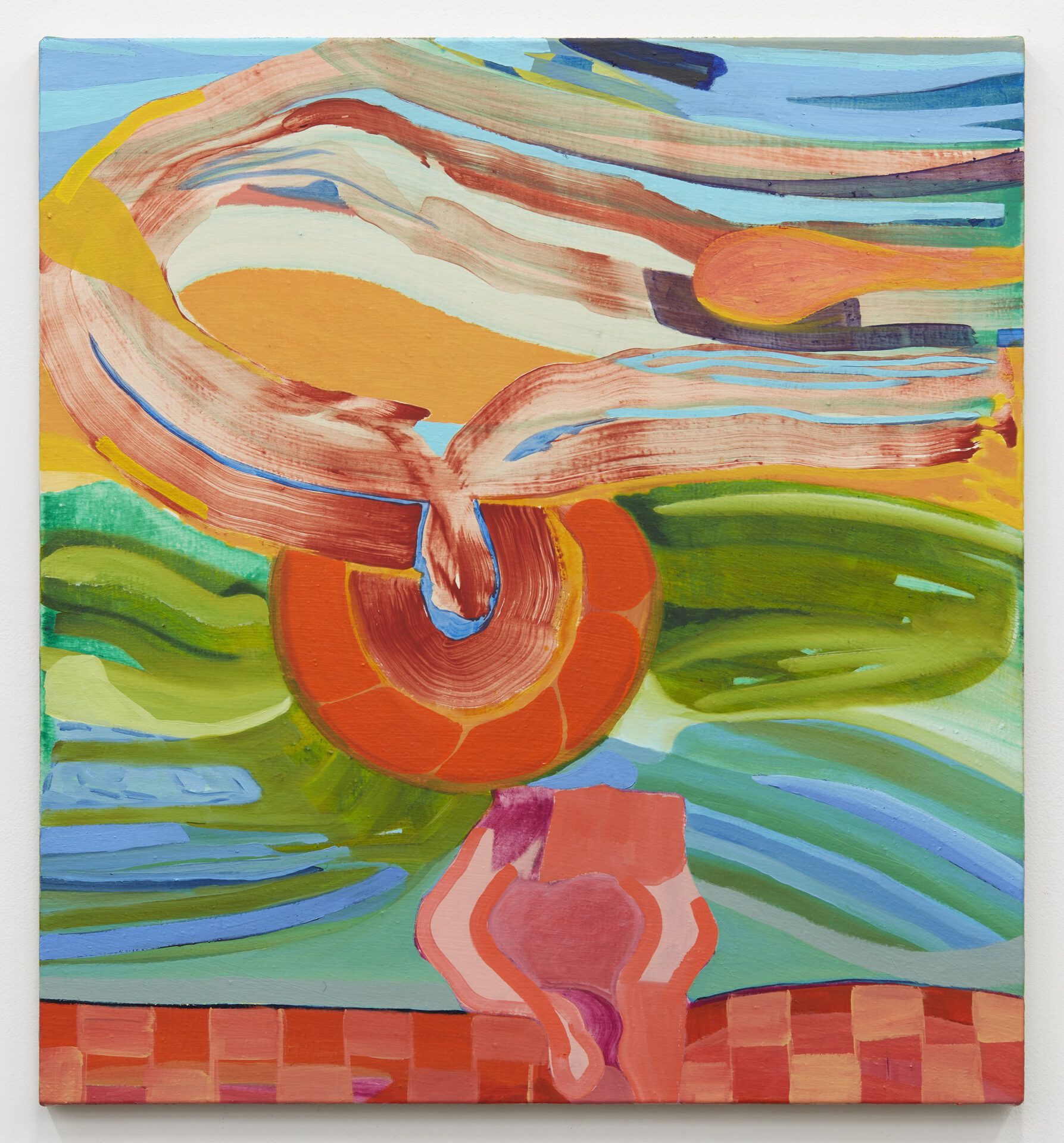

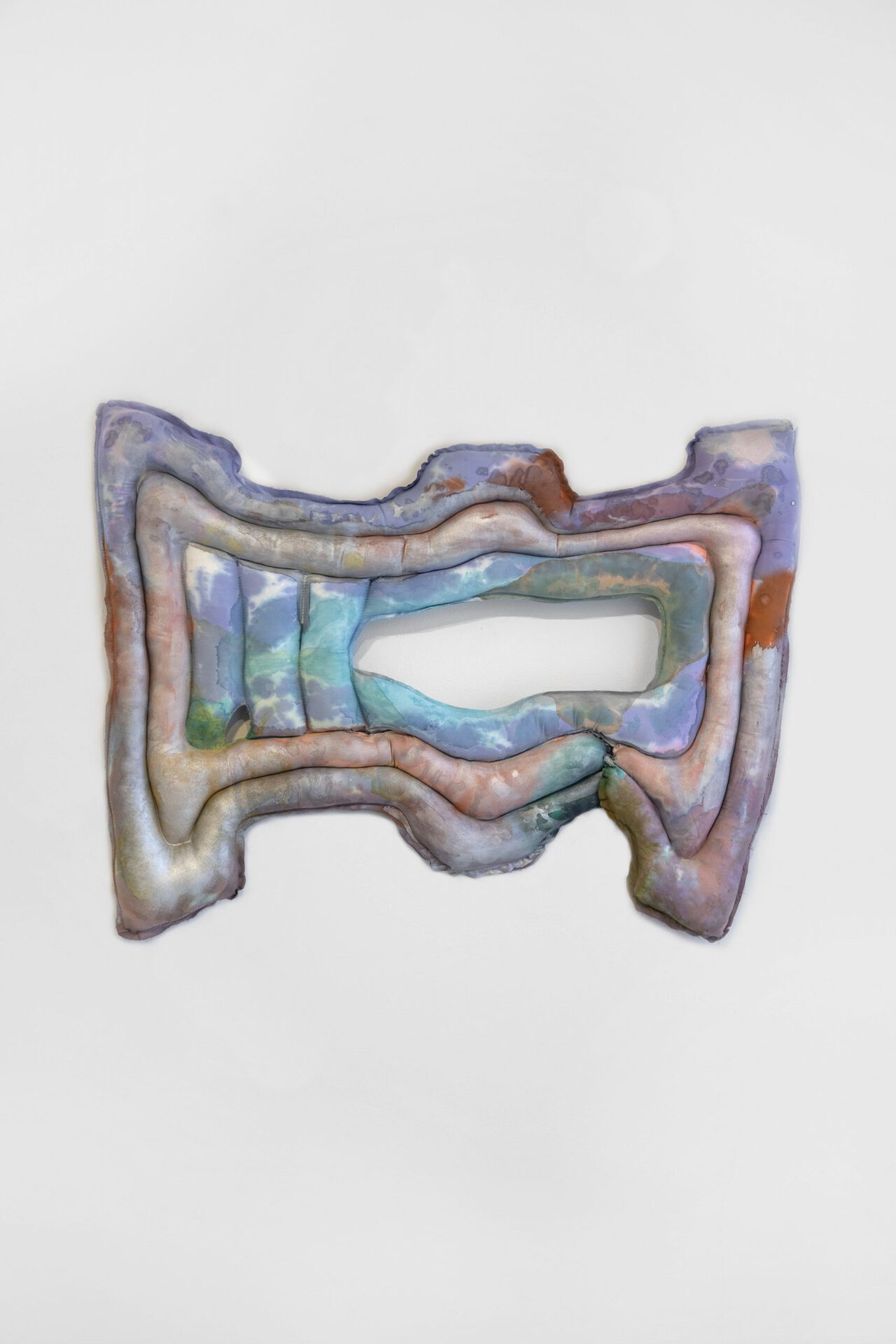

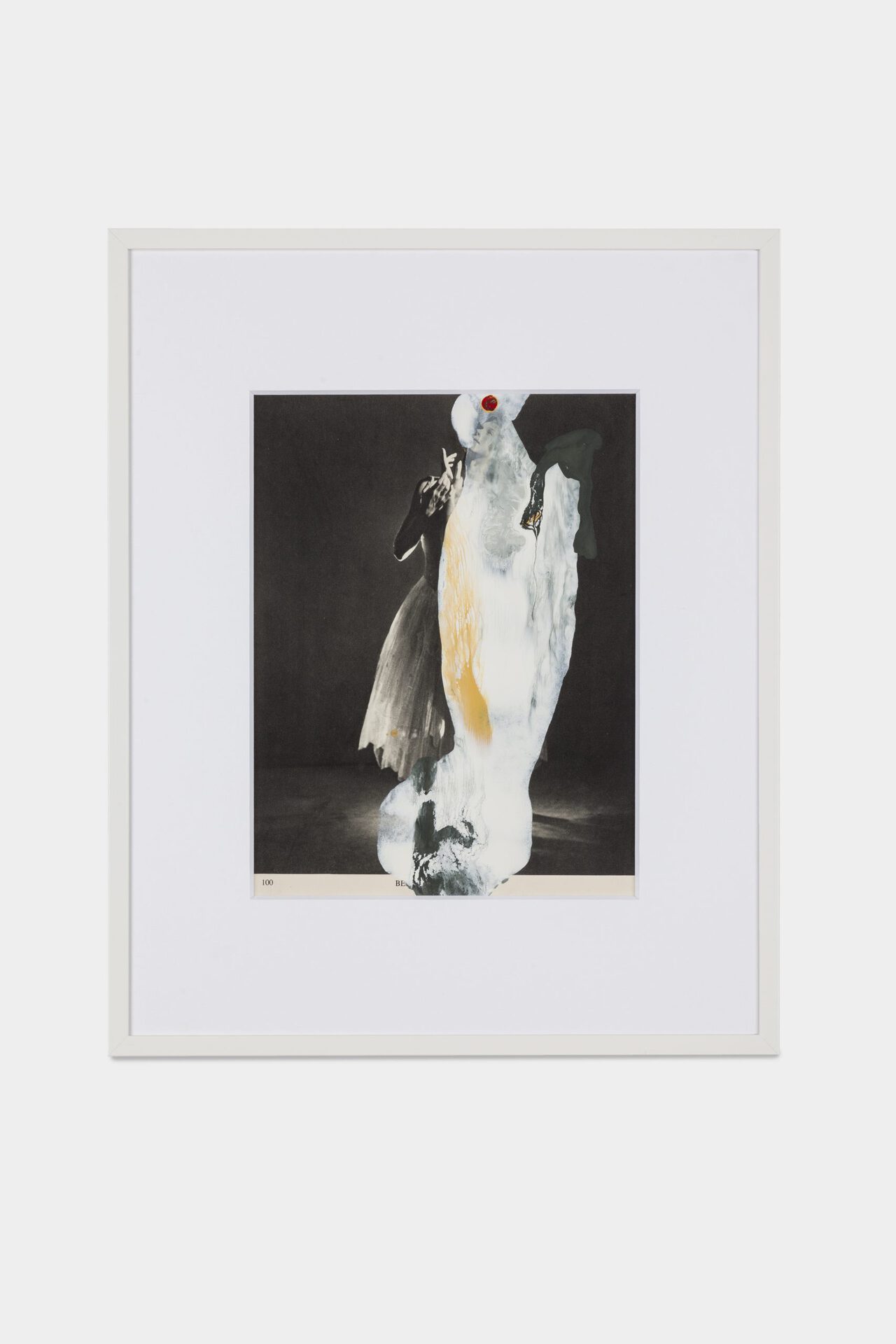

Hans Breder, Lili Dujourie, Marley Freeman, Linder, Meg Lipke.Text

At the beginning of 1930, when René Magritte was experimenting with the physical conventions of painting itself, he created L’Évidence éternelle, a standing nude of his model and wife, Georgette which is divided into five separate framed sections. L’Évidence éternelle is one of Magritte’s toiles découpées or cut-up canvases. It exists between painting and sculpture, and Magritte referred to these works as objects, not paintings. With the toiles découpées, Magritte forced the viewer to complete the image in his mind.

In 1948, Magritte completed another version of the work in which the model is portrayed in a frontal view. He attempted a third version in 1954. The completion of this last version remained uncertain since, until recently, only three canvases have been traced: the face, the breast, and the knees. Magritte offered the canvas of the breast and the one of the knees to Suzi Gablik, an American author who lived with the Magrittes for eight months in 1960. Gablik kept the knees and sold the breasts to Robert Rauschenberg.

L’Évidence éternelle brings together five artists who deal with the delineations of space and perception and of abstraction and figuration. They break up, layer, stitch and fracture images and by doing so reflect the limits of human perception, showing that the reality we perceive is fragmented. Aware of the tension between composition and fragmentation, their work asks the viewer to mentally reconstruct a whole from separate parts.

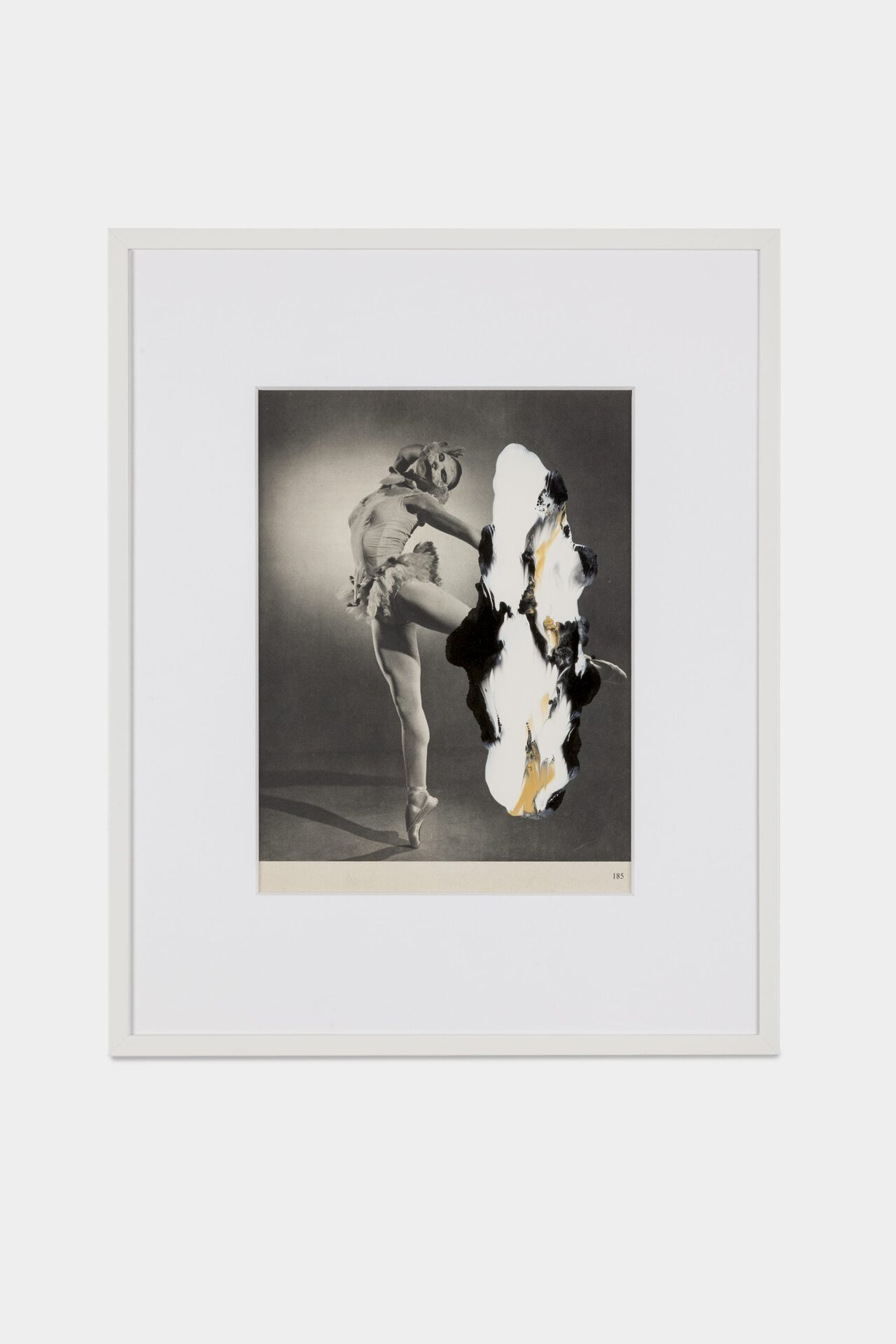

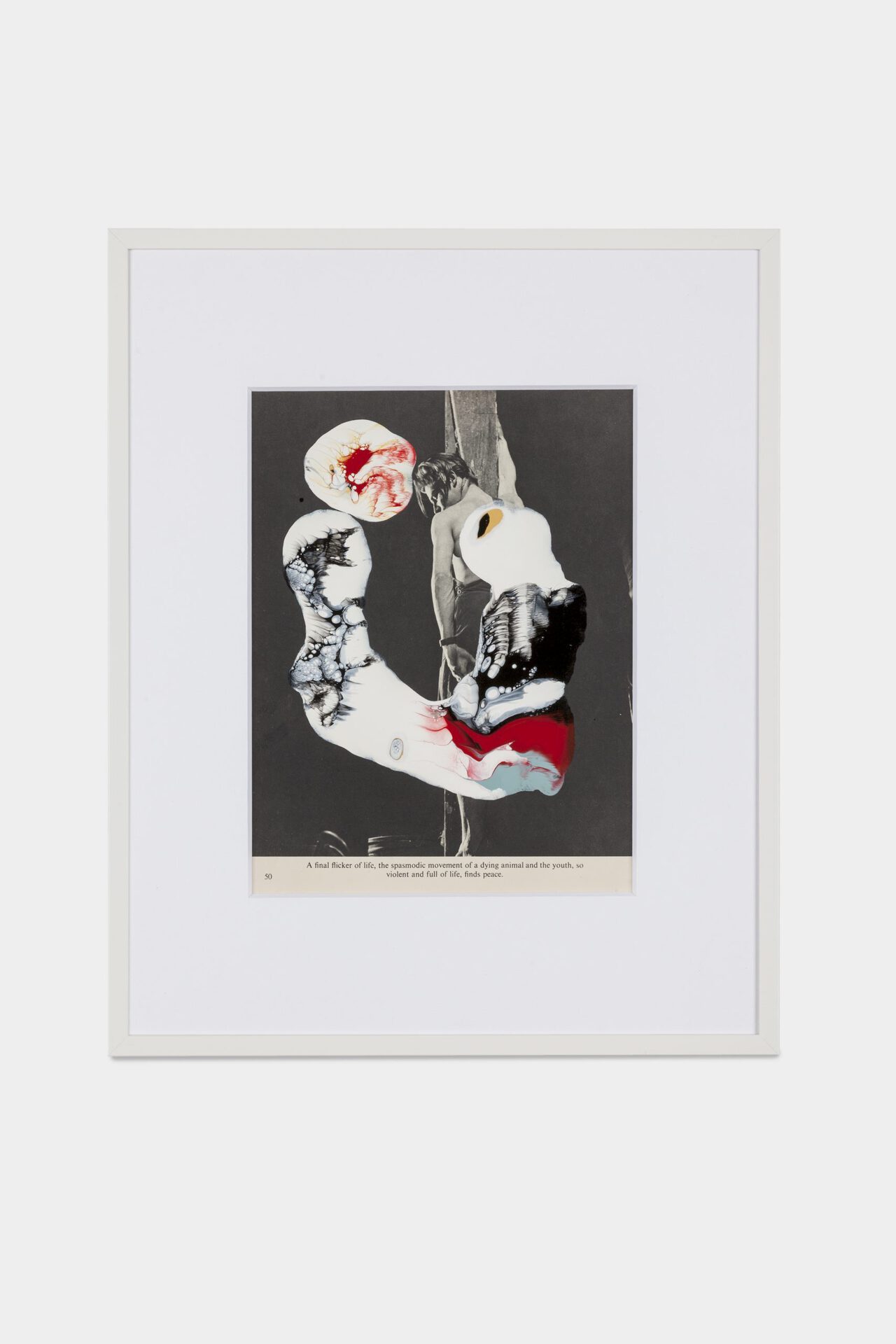

Hans Breder uses a mirrored surface to create a connection between space, body, and the fragmentation of form in his Body/Sculpture series from 1969-73. The mirrors not only dissolve the boundaries of space but disorient the observer’s view of the nude models, which include artist Ana Mendieta lying on the sand. Like the works of Linder — in which she conceals images of ballerinas with splashes of enamel paint — they incorporate classical sculpture and dance as well as body art and performance.

Meg Lipke bridges diverse textile traditions and modes of painterly abstraction in her practice. Her vibrantly colored works are cut and sewn out of canvas and tightly stuffed with polyester fill. She sees these surreal wall-mounted soft objects as paintings. Their sculptural presence suggests empty picture frames or the interior of the body. The canvas is used as a skin and painted and stained in pastel and iridescent colors with folkloric and psychedelic patterning. The image-making of Marley Freeman also relates to textiles and their varying levels of transparency. In her paintings, she weaves together patches of color. She builds layer on layer with opaque and transparent brushstrokes, blurring the previous gestures to fragment the moment of their action. In her minimalistic collages from the seventies, Lili Dujourie uses pieces of colored paper that overlap each other. The emptiness around the textural composition of torn edges, creases, and tears is as decisive as the fragments. In between presence and absence, these still lifes do not depict anything other than their own forms.

Louis-Philippe Van Eeckhoutte