Archive

2022

KubaParis

sadness reigns

Location

Galerie MARTINETZDate

19.05 –24.06.2022Photography

Tamara LorenzText

“I become a cyborg myself”

The desire for deep concentration

Hope. Solidarity. Community.

How Mary-Audrey Ramirez searched for peace. And found it, of all things, in a thawing alien.

By Frédéric Schwilden

And there lies Shrimpboy on the floor, and nobody knows how he got there. This large, smooth, white and in some places slimy alien that the artist Mary-Audrey Ramirez has named Shrimpboy because it resembles an oversized prawn.

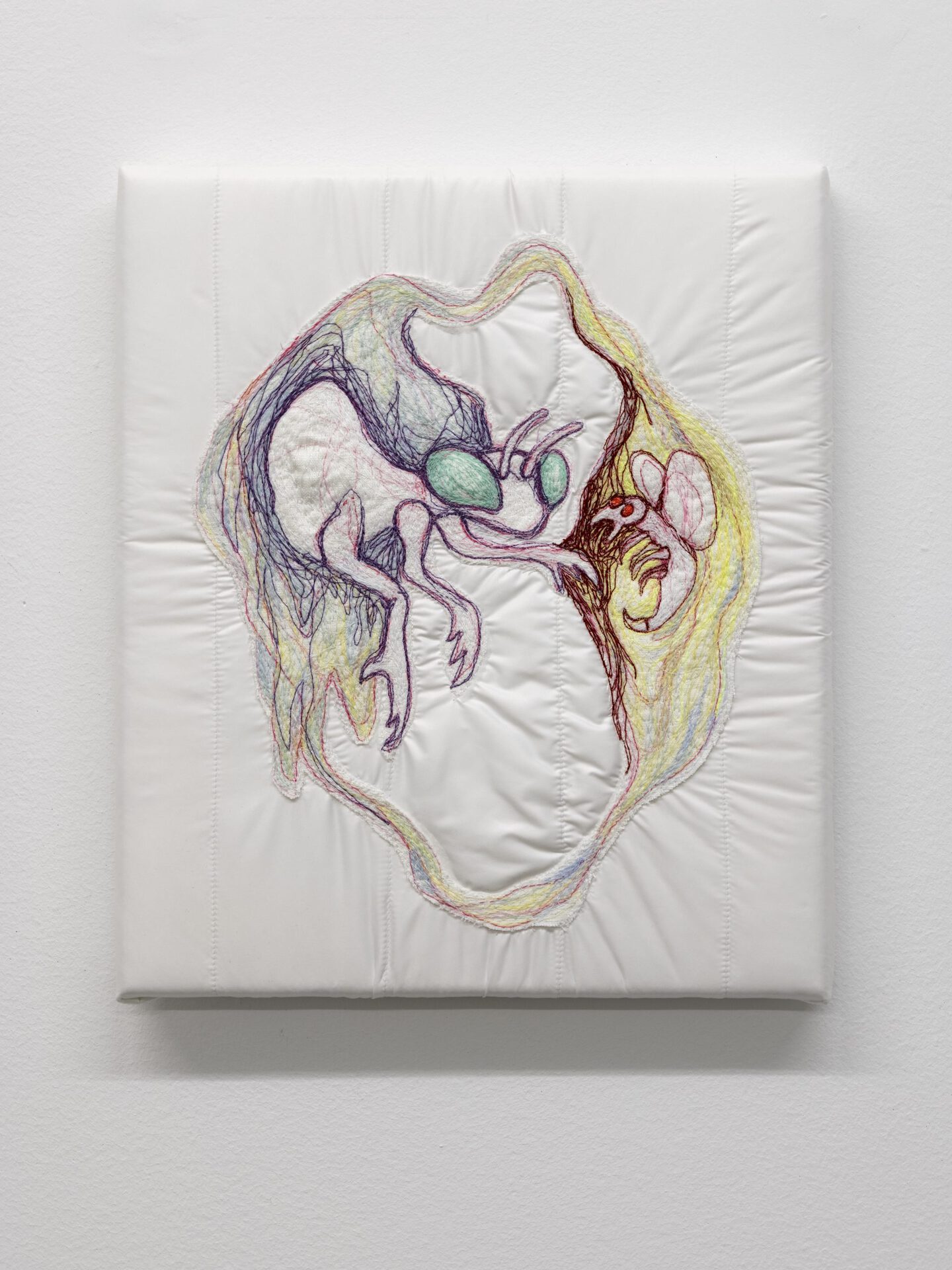

Shrimpboy’s body is curled into an oval. Motionless. He possesses not a single pigment of colour. His exoskeleton consists of ten compartments. He is slowly thawing, Ramirez says, somewhere on a planet far, far, away. Is he the first of his kind? Or the last?

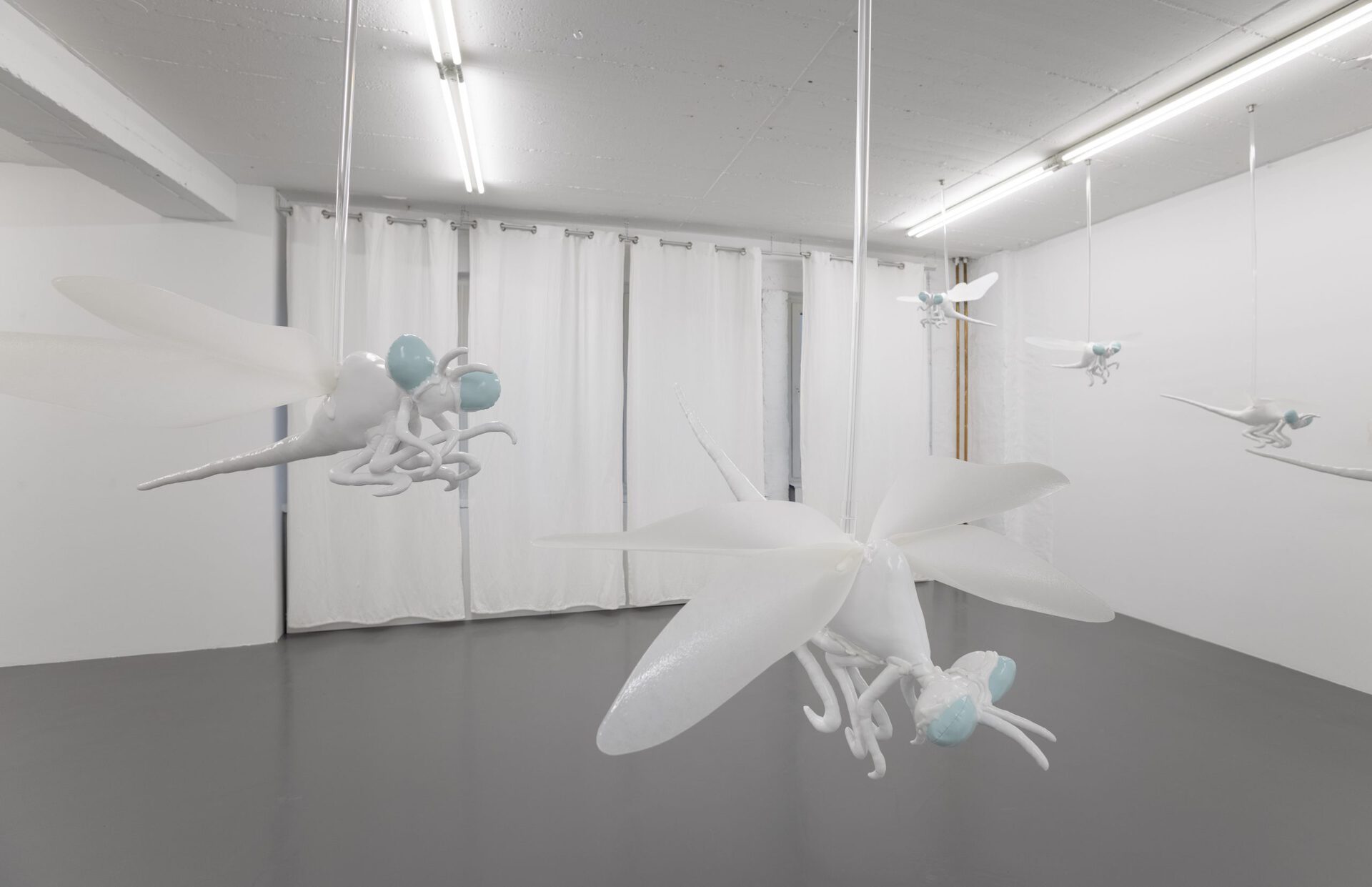

Other beings that look like oversized dragonflies hover above. While Shrimpboy is still only a growing larva, the dragonflies are adults. Do they want to take him with them? To help him? To raise him like a foundling? Be there for him regardless of species, as the inhabitants of the jungle were once there for Mowgli, the human child?

There is a great tenderness to the scene. A sadness. A loneliness. Completely alone, one thinks. But there is also hope, solidarity, community.

The exhibition ‘sadness reigns’ radiates an incredible calm. It is a deafeningly quiet rebellion against the zeitgeist of rapid cuts, bright colours, split-second attention spans and pumped-up bass.

Mary-Audrey Ramirez, 32, is a child of these times. The canon of her generation, brought up on the internet and in front of computers, is Grand Theft Auto, K-Pop and Netflix. This generation is the first to know that knowledge encircles us like air. They no longer need to know anything, they just need to have learned where to look. On Wikipedia, in Reddit forums, on the Darknet, on Youtube. This is how the digital-neural network of a new consciousness has come into being. Of course, Ramirez transcends country, language and media borders. Computer games, pop music, films, classical art history, fashion, high and sub-culture – it all plays its role. Caravaggio, Quake 3 or chaos theory.

From the same perspective, artists like LuYang or Jacolby Satterwhite create exaggerated brain noise. Blood flows, unicorns fly through the image, sex, dance interludes, everything and nothing whizzes by at the speed of light for a few seconds in animated video works, like TikToks or Instastories. In the sixties you had to take LSD to experience something akin to that, today you view art. In exhibitions that can hardly be distinguished from over-excited theme parks. They also serve as a backdrop for consumers to stage themselves. Never before have so many selfies been taken as in exhibitions these days. The art and the thoughts of the artists thus fade into the background. They become the stage set for thousands of micro-influencers.

With ‘sadness reigns’, Mary-Audrey Ramirez provides a counterpoint to this. “Art is bright and gaudy right now. But I have a desire for deep concentration. For calm.”

The absence of colour makes the exhibition feel like walking in the snow. Everything is more subdued, calm, as if in slow motion. In addition, white art shown in the White Cube is barely photographable, hardly instagrammable.

“I want my art to be an experience again. I want people to become explorers, like the first humans on a new planet,” says Ramirez. Art has to be perceived through one’s own senses again, and not through the lenses and image editing processes of smartphones. You see almost nothing of Shrimpboy and the dragonflies through a smartphone. They simply disappear. You have to bend down yourself, see them with your own eyes.

Yet Mary-Audrey Ramirez’s art is not reactionary and anti-modern. On the contrary. Ramirez is not Ted Kaczynski. She is always working to learn new techniques, to understand them. Playing with them, applying them, mastering them.

Shrimpboy and the dragonflies were created as 3D models in a computer programme before being transformed into the material form of sculptures made of wire frame and fabric. Despite modern technology, they appear like marble antiques, timeless like Greek sculptures, but equally smooth and futuristic like Apple products.

“I become a cyborg myself,” Ramirez says about her method of working. “When I work in the digital space, I have to think like a cyborg. But when I bring things back to the analogue world, there’s no more Crtl +Z. If I cut the fabric wrong, I have a problem.”

These difficulties are, however, not visible in reality. Ramirez works with absolute precision. Her sculptures are not only conceptually perfect, but also perfectly handcrafted. She clearly doesn’t need Crtl +Z.

Frédéric Schwilden