Archive

2020

KubaParis

Die ZWEITE HAND

Location

stadiumDate

28.02 –17.04.2020Photography

groupshow.euText

Die ZWEITE HAND

Niclas Riepshoff

Cluttered Spaceships: Touching upon the Connectivity of the Closet

“Die Zweite Hand” was a weekly West Berlin paper that published personal ads, shoutouts and all sorts of stuff to be sold, traded or given away. Starting out in 1983, with three people, an answering machine and a photocopier in the tiny space on Potsdamer Straße 70 that is now hosting stadium, “Die Zweite Hand” quickly became a widely popular publication that people were allegedly queuing for all the way from Kurfürstenstraße. In pre-eBay times, when the phone could literally be off the hook, the gazette featured only short ads without any images, but within a few months the print run went up to 38.000 copies. Facing regressing wages during the recession, the three founders intended to establish a platform for readers to engage in a circular economy, a printed fleamarket to exchange thoughts and goods – “against crisis and for communication“, as they stated in its first edition.

Selling the things one owns, that one doesn’t want around anymore, is a strange process these days. After decluttering the closet, one almost can’t be bothered to write a detailed description or take a proper photo, filling resell websites with neglected images. With mostly anonymous profiles, the use of these websites distinctly differs from the curatorial approach to social media and instead exhibits what was stored in clandestine compartments. Having to make visible the rejected parts of one’s own:

How to suggest a desire for the undesired?

*

Marie Kondō promotes an essentialism of pure positivity that meets the demands for a curated self, ignoring the joy that lies in engaging in the thinking of cluttered, messy, patchy and entangled worlds.

*

“Don’t tell anybody! No-, nobody! Be good! Be good!“ When we encounter E.T. dressed up in the closet – dressed at all – in a wig, a skirt and jewellery, gender performativity’s effects are in full swing: only once it sounds like Gertie and Elliott disagree about the binary pronouns they use to refer to the alien, but to use gendered pronouns in the first place is what anthropomorphizes E.T. – dressing the alien in human drag.

“Home?“, E.T. says while standing in front of the closet, just having acquired a few English vocabularies. “You’re right, that’s E.T.’s home”, replies Elliott, but the alien decidedly moves towards the window and raises the decorated finger that casts a shadow on the boy’s face, pointing outside, wanting to get in touch.

*

They remember a recurring dream they had as a young one, standing on top of a tall closet, the entire thing about to tip over. Tumbling down they remained a stiff extension of the wooden piece of furniture, one axis, until they would hit the laminate floor, crashing into subjecthood again and again. For them, the closet was no hideaway – it was an unwanted pedestal, a monument exposing the young one who had not even articulated yet what others already called them. But how did they get up there?

*

For the untouched young one, reading that one should sit on their hand to make it fall asleep is exciting news: It promises the feeling of another’s touch on their pubescent genitalia, a third hand doing the job, created by their own alienated body.

*

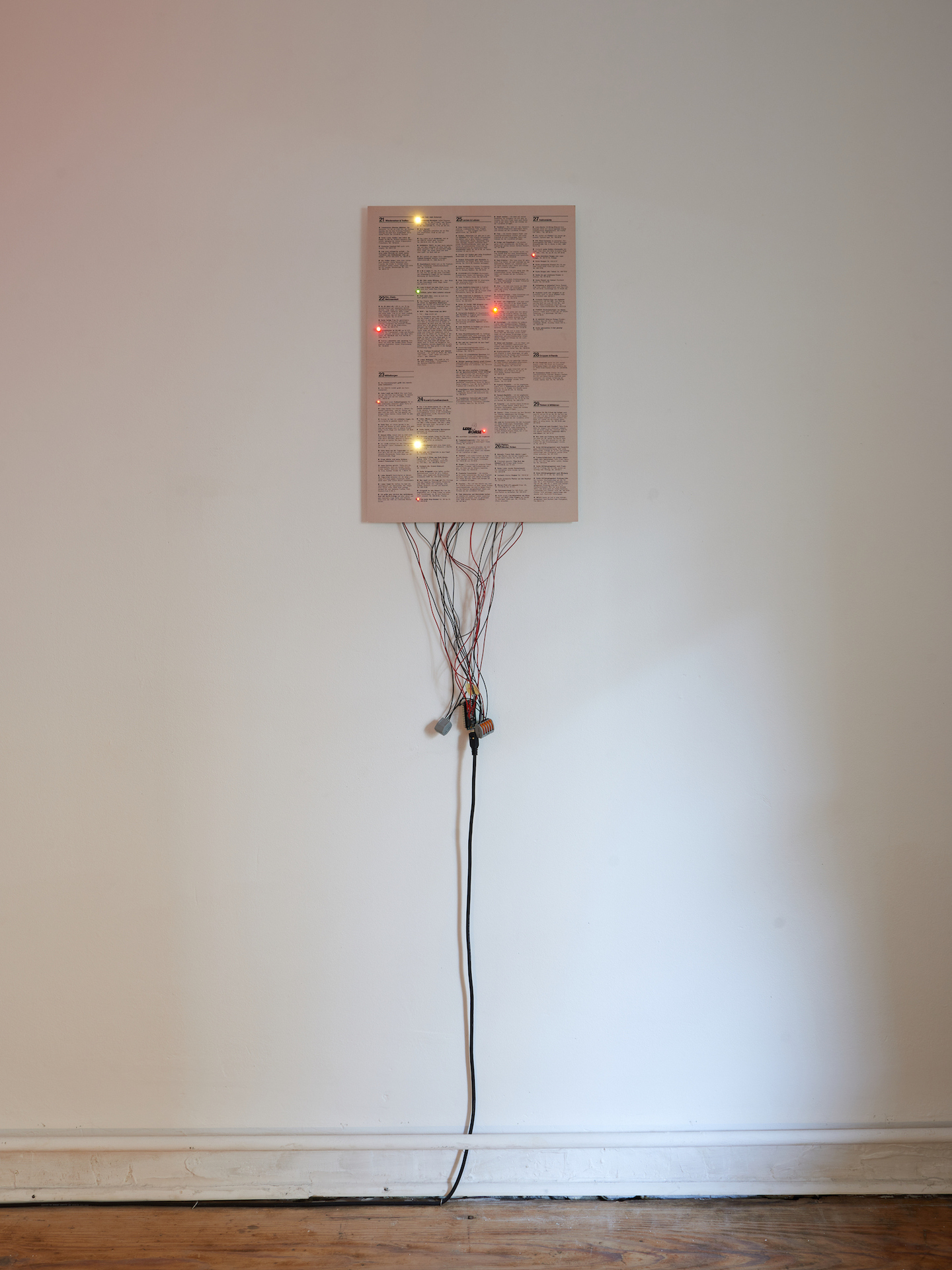

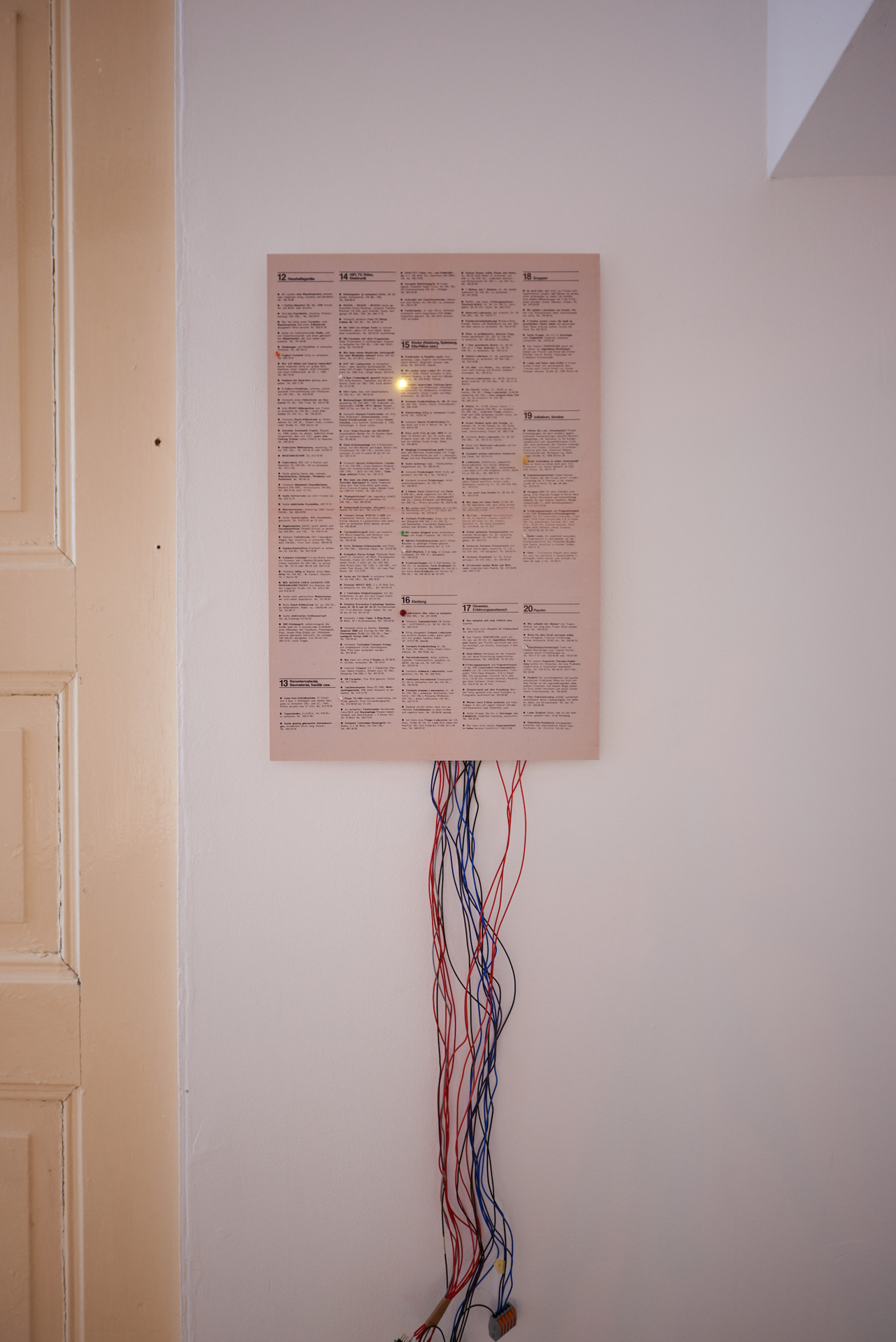

In recent works, Niclas Riepshoff has been dealing with those stages of life that biopolitics are most concerned with: reproduction, infanthood and old age. In Vitro (2019) depicted the moment of artificial fertilization, interpreting the design of the classic Wilhelm Wagenfeld lamp as a steel cannula entering the vitreous ovum, injecting LED sperm. 3 Poses for a Newborn (2018) plays with the narrative of artworks being the artist’s offspring, raising questions about queer parenthood, aesthetics of authenticity and signature styles. Absolutes Gehör (2019) consisted of a group of sculptures modelled after hearing aids and the artist playing high pitched notes on a ute while wearing prosthetic makeup that had aged him about 50 years.

His exhibition “Die Zweite Hand“ at stadium, this semi-public gallery space hardly bigger than a walk-in closet, began with a site-speci c research, looking into the space’s peculiar architecture and its former usage. Read in the context of mentioned works, the show proposes myriad connections between queer subjectivities, private and public spaces, confessions and communication strategies, challenging the normative process of the coming-out as an initiation into both subjectivity and subjection.

- Christopher Wierling

Christopher Wierling