Archive

2020

KubaParis

options-options-e2-80-a8a-conversation-between-vika-prokopaviciute-and-katharina-hoglinger

Location

Wonnerth DejacoDate

28.10 –18.12.2020Subheadline

*on the occasion of the current exhibition: Katharina Höglinger – Zunge verlieren (losing tongue) at Wonnerth Dejaco, ViennaText

left: Katharina Höglinger, photo: Lisa Edi

right: Vika Prokopaviciute

VP: The moment I enter the gallery, I am losing my tongue, too. Here they are, all these generous options: large format fabric paint, marker and acrylic ink on linen,

unstretched painting on canvas acting as a mural, a book as a collection of hand-painted t-shirts, neatly framed small-format oil paintings on cardboard, hand-painted sweatshirt pointing with its sleeves towards oil paintings on canvas.

Kathi, I think I am in your painting!

[caption id="attachment_72255" align="alignnone" width="660"] Installation view, Zunge verlieren (losing tongue), photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Installation view, Zunge verlieren (losing tongue), photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

KH: Ha, I love that! I was hoping that you were in it. To be honest, I don’t produce the material outcome of my painting – the resulting objects – so much for myself. It is rather something I would love to throw out into 'the world', to some people who can take care of them. When someone buys a work, I feel like they would salvage it, bring it where it will have a sweet home it deserves. That is maybe also the reason why I wouldn't want my work ending up with some person or in some place I don't like or, even worse, in storage forever. VP: As a painter, you are facing an enormous amount of possibilities. Every step, every layer is a decision, a new turn, which could lead to a, sometimes, unexpected result. To choose one thing means to say 'no' to another. Sometimes I am afraid of choosing one method, afraid to stop 'inventing'. So very often, one painting would be the negation of the previous one. Every second painting is 'yes', while others are 'no', like even and uneven numbers. It seems like you found a way to escape this frustration. I want to talk to you about options. How do they appear and how do they develop? Is it about saying 'yes' to all methods and challenging yourself and the beholder? Is it about saying more than you can? [caption id="attachment_72263" align="alignnone" width="660"] Katharina Höglinger, yes no yes no yes no yes no – dance, 2020, oil on canvas, 30 × 42 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, yes no yes no yes no yes no – dance, 2020, oil on canvas, 30 × 42 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

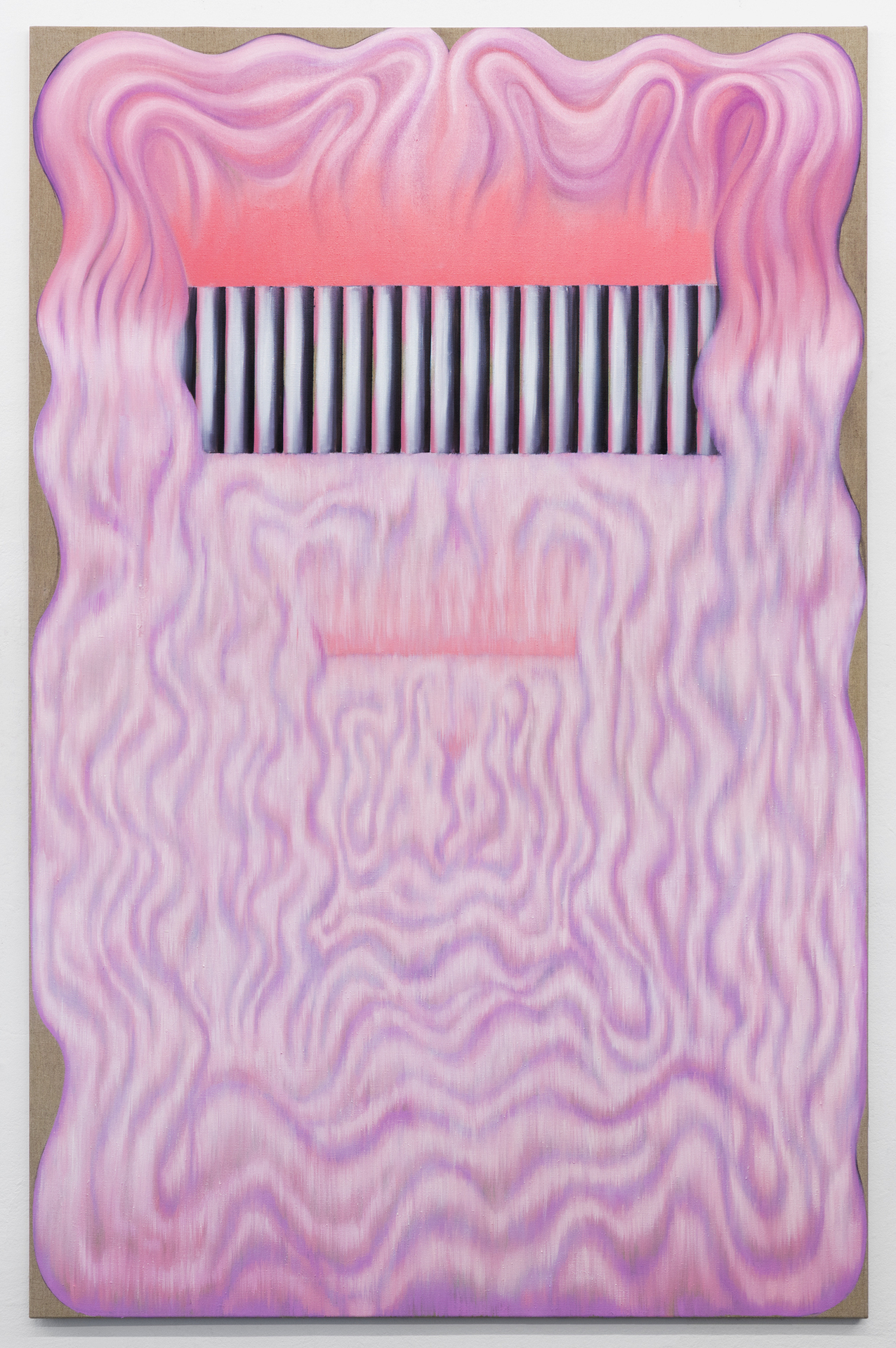

KH: I don't think I am saying 'yes' to all methods. For example, I wouldn't really dare to produce objects, but not because I'm not interested. I would have the feeling I’d just lose it totally. Like you say, there are already so many options, it's some kind of FOMO, almost. The main feeling is that I want to figure out what to say. There are so many great paintings and painters, and I know it is not really possible. But also, I don't want to repeat history so much. So maybe it's this desperate longing for creating something 'meaningful' (I hate this word), and producing like a maniac, somehow very exposed, somehow hiding in the studio, gives me hope in this quest. VP: Do you know about the exploding cucumber? It is a plant which shoots its seeds around, in a weird way 'throwing into the world' reminded me of it. Spritzgurke! [caption id="attachment_72251" align="alignnone" width="660"] Vika Prokopaviciute

Vika Prokopaviciute

Pale Grey Brush Fire, 2020

200 x 130 cm, oil on linen[/caption] [caption id="attachment_72252" align="alignnone" width="660"] Multiplying Pale Brush Fire, 2020

Multiplying Pale Brush Fire, 2020

200 x 130 cm, oil on linen[/caption]

KH: Oh yes, we always fancied exploding them with our fingers as children, and still up to now. I imagined it would be an actual cucumber which is exploding when it's 'grown up'. I have to paint that. Also, when I think about your paintings, it's not so much that they are exploding, but continuously spritzing (not actually true, it's more splashing and flowing, but I like the relation to the German word), like an endless application of colour that doesn’t stop from one painting to the other, but just changes. And even though you would often say 'no' and sometimes say 'yes', for me it's so important to see the whole action. Maybe for me, it's a bit like the contrast to that, it's more 'stop and go'. Although I can totally relate to what you said about each painting being the answer to the last one. VP: Do you mean like 'stop and go' and move to the next one? Kiss-and-ride! I see it in your small-format paintings on cardboard. They are more like vessels and more pronounced as portraits or still lifes, for example. Large-format paintings are multi-functional in a way: a still life is not only a still life but also a portrait and a landscape. What was the difference in the process? [caption id="attachment_72271" align="alignnone" width="660"] Katharina Höglinger, On a Plate, 2020, oil on cardboard, 27 × 36 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, On a Plate, 2020, oil on cardboard, 27 × 36 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_72276" align="alignnone" width="660"] Katharina Höglinger, Self-Portrait in the Woods, 2020, oil on cardboard, 27 × 36 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, Self-Portrait in the Woods, 2020, oil on cardboard, 27 × 36 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

KH: There is a certain amount of energy in one painting, and, until now, I have never managed to have different amounts in different sizes — metaphorically speaking, because I would not be able to measure it. So, with tiny formats, it gets very condensed while with large formats, it almost feels like loosening the canvas, particularly with unstretched ones. I have the feeling your amount of 'energy' (it's not the right word maybe) is more exponential with size. VP: Small-formats weigh the same as large-formats. Reminds me of 'What's heavier? A kilogram of steel, or a kilogram of feathers?'. Maybe it has something to do with scale, the focus distance. I try to keep this distance more or less the same. You know, I paint sometimes large formats with the same brushes as small formats, even big parts. It gives me the feeling that 'I did my job', put enough labour into it. Weird, haha. And the scale stays the same. KH: So in that sense, your paintings have their own weight, like a kilogram of Vika Prokopaviciute Painting. You create your own measurement. VP: Or one joule of Katharina Höglinger Painting, if we talk about energy. KH: I paint every format and every surface with different brushes, colours, technique and focus distance. Using lots of different materials is a huge interest of mine. Here we are again: it's that matter of different decisions or options. VP: In 'Being Ecological', Timothy Morton says that the whole is always less than the sum of its parts, although we used to think the other way around. It can be also about painting. In painting, feathers can be heavier as steel. This makes me think about gravity and your '(purgatory)'. It looks like you turned the canvas, but once you explained you didn't. I like to feel fooled in this case. [caption id="attachment_72280" align="alignnone" width="660"] Katharina Höglinger, (purgatory), 2020, oil on canvas, 90 × 110 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, (purgatory), 2020, oil on canvas, 90 × 110 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

KH: 'Gestalt psychology argues that the whole is different than its parts, not greater than ...' I like this idea of equalizing. For me, it is a way to deal with the uncountable, the endless amount of paintings which are produced, which are situated in and come from different scenes, different circles, different environments, different ages, different motivations, different urges. There is this great talk by Amy Sillman, where she speaks about drawing in the continuous present. She shows a slideshow with drawings, and to each of those drawings, she adds a verb that shows how democratic the process of drawing is. I would go further and say with painting it's almost the same. She shows all these works by those famous people without mentioning their names, which I borrowed when I did a public talk amongst painters with an open discussion called 'Painting and the self & itself'. I played a slideshow with a mix of paintings related to the topic by my Viennese colleagues, old masters, famous painters, outsider artists, my daughter and myself. And people in the audience did not know about it, and some saw their paintings. It’s this kind of equalizing that I like a lot. But to equalize that also makes me feel very anxious about being a professional painter. And then I think of musicians and writers: from this distance, I can understand that it is altogether important. So back into the loop! VP: Equalizing would mean moving towards the non-binary. Like Amy Sillman says that stating that drawing is a pre-painting would be wrong, although it shows the intelligence of the first. Drawing is refusing the logic of primary and secondary. I start with a drawing and later create the surface out of it, filling it with paint. Painting becomes a surface between the lines. Or I would 'paint' a line like I would paint a wire or a ribbon. Is there a difference for you between drawing and painting? KH: I know what I would call drawing and what I would call painting. I make a difference in using these terms, but definitely not in values. A two-minutes tiny drawing can be as strong as a two-months huge painting. Drawing for me is: creating motives, focusing on the narrative, putting lines in conversation, creating tension. But it doesn't necessarily mean that you can't use (liquid) colour. Painting is more about texture, light, space and effect and of course, how colours work and behave. VP: It fits the idea that you put the same amount of energy in your paintings, equalizing hand-drawn gloves and big-formats, dissolving one substance in another one until the borders are disappearing. Also inviting other artists to participate in this process: for example, Lena Sieder-Semlitsch, who created the storage table for your T-shirt book. The table is like a transformed painting — wood and canvas support your book, and it becomes more potent having such a display. Also, it reminds me of the pochade box, the one plein-air artists use as an easel and to store their supplies. [caption id="attachment_72267" align="alignnone" width="660"] Katharina Höglinger, The Secret Life of KH, 2019, oil, oil pastels, marker, paper, T-shirts, cotton gloves, poplar and pine wood, cotton fabric, velcro fastener (Storage table: design and construction – Lena Sieder-Semlitsch), 65 × 102 × 76 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, The Secret Life of KH, 2019, oil, oil pastels, marker, paper, T-shirts, cotton gloves, poplar and pine wood, cotton fabric, velcro fastener (Storage table: design and construction – Lena Sieder-Semlitsch), 65 × 102 × 76 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

KH: At this point, a super big thanks to Lena Sieder-Semlitsch. She built the display, table and transport solution for my hand-painted artist book 'The Secret Life of KH'. Lena is working a lot at the interface between transportable kiosk and sculpture. When I asked her to build a box for the book, we came up with the idea of the box that was a table and also a suitcase. She used Molino for the padding, making the whole thing referential on so many layers. As you said, it reminds of a pochade box, and people keep adding pasting table. You know that Seinfeld episode, where Kramer made this coffee table book: 'If you don't have a coffee table, it turns into a coffee table.' VP: Maybe all these endless options free you from tags, claims, expectations. Inventing, sometimes reinventing, 'producing like a maniac', being too much, surprising yourself and the audience equals explaining yourself (to yourself?), being insecure in front of others, being vulnerable. And by not keeping it safe you find comfort in it. You mentioned in the beginning 'salvaging' the work. Rescuing it from the void by producing it and then letting it go, offering its vulnerability to others? To me this is a very pronounced characteristic of your works: they are inclusive and inviting. All these faces, vases, flowers, dogs, windows, lips, hands and feet, surfaces and textures are openly speaking to the one who is looking at them. KH: Also in a very literal way, salvaging the object from collecting dust in storage. I don't have this kind of relationship with my paintings which would not allow me to separate from them. But at the same time, it also feels like I have a responsibility. VP: Grown-up paintings, finally leaving the studio. I feel frustration sometimes to see paintings performing strangely in the exhibition. As if they are at a formal dinner where they act polite and watch what they (you) say, being aware of the context. Losing tongue, right? Perhaps they are more 'honest' at the studio. Here I see resistance: the unstretched 'Untitled' states its space, refusing to be a 'proper' painting; the museum gloves for 'The Secret Life of KH' play the art-handling game but, at the same time, they become a drawing object, too. How do you 'adapt' the surroundings for them? KH:I see that with your paintings and what you mean, but also, I really love when a painting goes to an exhibition or a wall somewhere in a living room or a showroom. They can say much more and fully unfold, which in a tiny and crowded studio like mine is maybe much more difficult. There is resistance, refusal, defiance and the ambiguous (and maybe essential for survival and mental health) urge to please. There is no difference in their values, all objects are supporting each other. I just had a super important term added to my describing vocabulary. I was listening to the Deep Color podcast by Joseph Hart, and in the latest episode he was talking toCurtis Talwst Santiago, whom I admire a lot. In this conversation, one of them brought up 'intuition as a tool'. This is very important to me, and until now, I was never able to put it right with words. Sometimes we tend to think of intuition as something we can't control. But intuition is something you can use and apply decisively. It is not something intangible; we can use it as consciously and strongly as our brains or our hands. And all the things mentioned above are parts of this interplay. VP: Perhaps this interplay makes them seem to be in progress as if they are changing (are being painted) in front of my eyes, right here. 'Untitled', the large-format unstretched painting is transforming every time I look at it. It hugs itself, then it holds itself on the wall, and the next second, suddenly, a boxing glove appears. How do you deal with its constant developing? Do you control it or take its offer? [caption id="attachment_72268" align="alignnone" width="660"] Katharina Höglinger, Untitled, 2020, oil, acrylic and marker on linen, 164 × 182 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, Untitled, 2020, oil, acrylic and marker on linen, 164 × 182 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

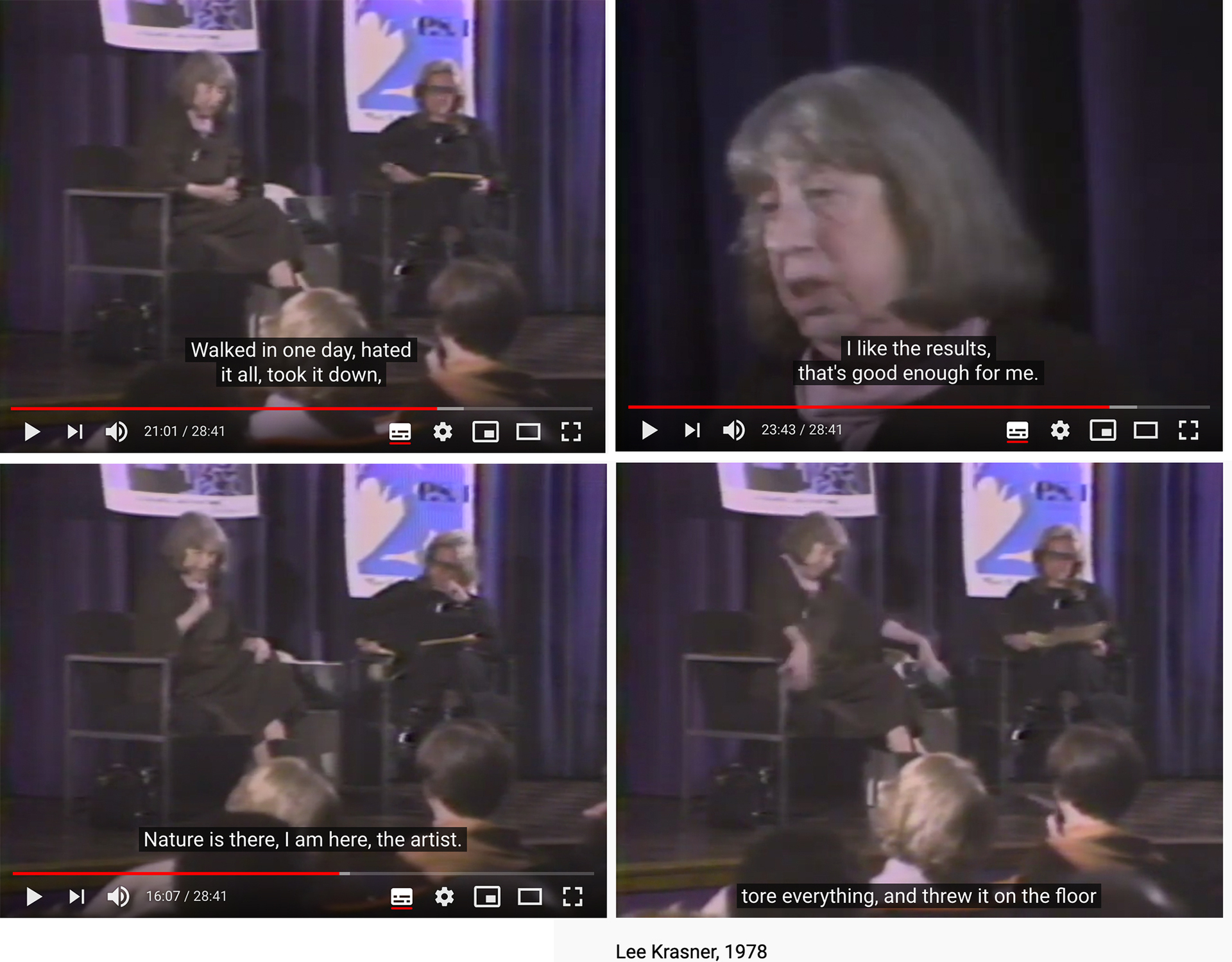

KH: Maybe I answer with a photo story I just screenshotted from thisLee Krasner interview:

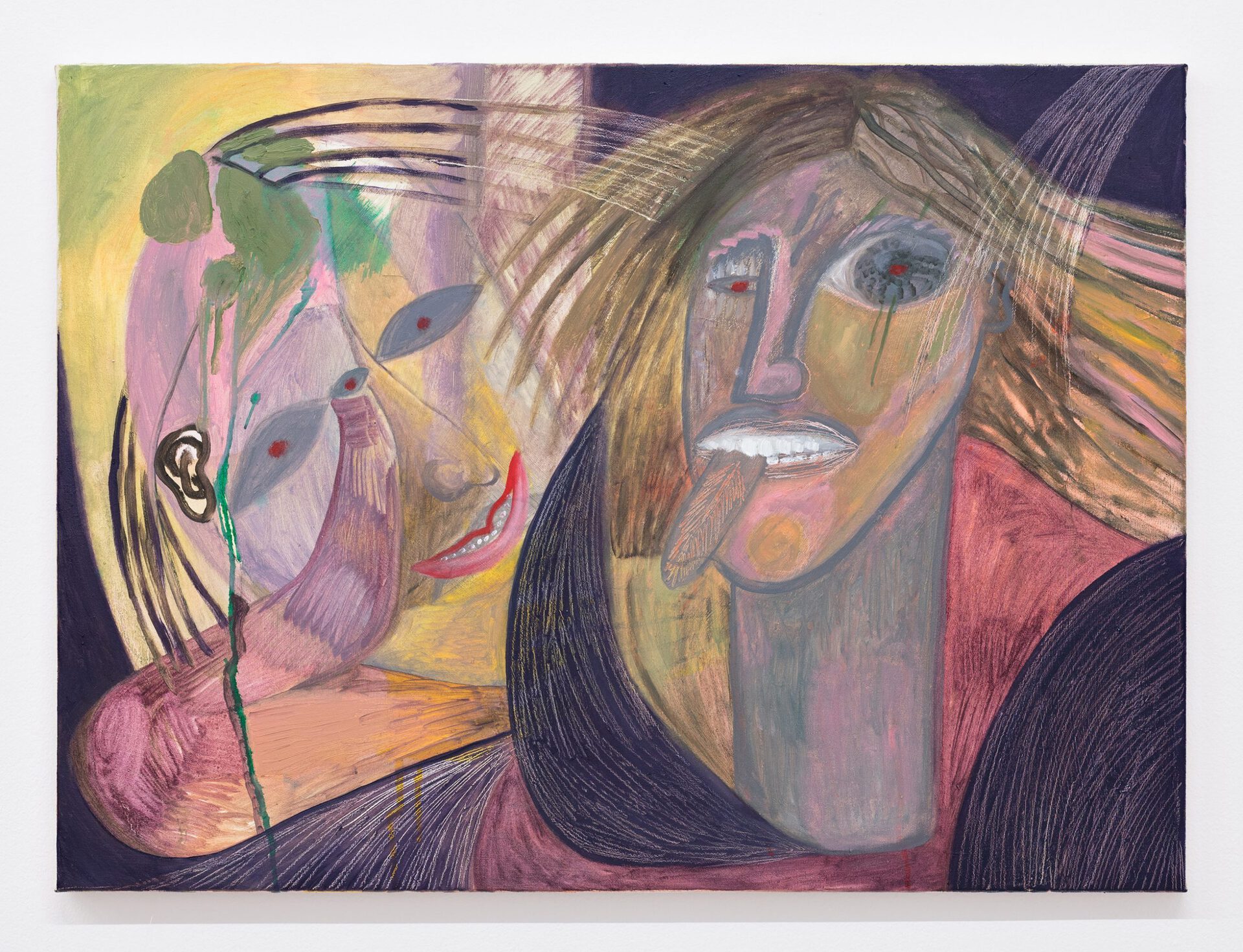

VP: We talked once about painting problems, and there was your painting '(vanitas)', which you painted over several times, adding more elements, merging faces. And we were like: 'Where is the problem?' It was clear that you, exactly you, would mix a lot of things, creating a strange dreamy mass of all possible techniques and materials (options again!). But you were more concerned about the opposite ones ('Bad Flower' and 'Hello Darling'), so light and so easy like you didn't expect it from yourself. Usually, one would be afraid to stop too late, but in this case, it was another way around: 'why would we want to do the least'. Does it make sense? [caption id="attachment_72265" align="alignnone" width="660"] Katharina Höglinger, (vanitas), 2020, oil on canvas, 85 × 70 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, (vanitas), 2020, oil on canvas, 85 × 70 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_72266" align="alignnone" width="660"] Katharina Höglinger, Hello Darling, 2020, fabric paint and marker on linen, 124 × 190 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi

Katharina Höglinger, Hello Darling, 2020, fabric paint and marker on linen, 124 × 190 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi

[/caption]

KH: It does. But what makes no sense and also always, of course, surprises people, because nobody would ever expect that from my work anyway, is that from time to time I'm really struggling with what one calls 'the style of a painter'. And then I have a feeling I should find one style or in the end, one thing, will develop it, but I'm just not there yet. Also, people keep saying things like 'Oh, now eventually it all comes together' or 'I'm curious where this all leads to in the end' and I'm wondering: Is it like this, does it have to be like this, am I just lying to myself and I'm just not 'there'? But in the end, creating 'a style' is just not what my work is about. It's about something else and if I need to put it like this, that's a style, too. VP: Then I ask you the question inspired from a recent 'Talk Art' episode with Tracey Emin. Are you afraid sometimes of what you paint, of what you see? I guess it is not so much about fear but about perceiving yourself through the eyes of the audience. KH: I am afraid only when it is about frightening stories. But then it is more about being afraid of the topics themselves, not so much of the painting, and I am not so sure if I should show it to an audience. For example, after the terror attack, I made some watercolours which just freaked me out — I didn't do them on purpose. I was like: 'No, that can't be in your painting' (even though it was just abstract watercolours, I don't think anyone would have noticed, but the feelings I had were just too frightening for everything). The other thing, uncanniness, is very important to me, although sometimes, of course, a bit adventurous. It can happen that I deeply hate my painting, I really would love to cut it, burn it, paint it over or whatever, but then there is the same amount of love too, and that's where all the evolvement for the future paintings can happen. '(purgatory)' is one of those paintings, it's a bit too much of everything, and that's why I like it every day a bit more. Speaking of Tracey Emin, her work is different as she was always using autobiographical elements. People keep saying that about my work, too, but in my case, it is more the illusion of autobiography. I don't think one might know a lot about me by just seeing my painting. It's more like construction and deconstruction of roles, identities and expectations. I made this painting in 2018 with the title 'My heart is a clock, you think you know me. You don't': [caption id="attachment_72250" align="alignnone" width="660"] Katharina Höglinger, My heart is a clock, you think you know me. you don´t, 2018, acrylic & oil pastel on canvas, 14 x 18cm

[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, My heart is a clock, you think you know me. you don´t, 2018, acrylic & oil pastel on canvas, 14 x 18cm

[/caption]

Installation view, Zunge verlieren (losing tongue), photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Installation view, Zunge verlieren (losing tongue), photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

KH: Ha, I love that! I was hoping that you were in it. To be honest, I don’t produce the material outcome of my painting – the resulting objects – so much for myself. It is rather something I would love to throw out into 'the world', to some people who can take care of them. When someone buys a work, I feel like they would salvage it, bring it where it will have a sweet home it deserves. That is maybe also the reason why I wouldn't want my work ending up with some person or in some place I don't like or, even worse, in storage forever. VP: As a painter, you are facing an enormous amount of possibilities. Every step, every layer is a decision, a new turn, which could lead to a, sometimes, unexpected result. To choose one thing means to say 'no' to another. Sometimes I am afraid of choosing one method, afraid to stop 'inventing'. So very often, one painting would be the negation of the previous one. Every second painting is 'yes', while others are 'no', like even and uneven numbers. It seems like you found a way to escape this frustration. I want to talk to you about options. How do they appear and how do they develop? Is it about saying 'yes' to all methods and challenging yourself and the beholder? Is it about saying more than you can? [caption id="attachment_72263" align="alignnone" width="660"]

Katharina Höglinger, yes no yes no yes no yes no – dance, 2020, oil on canvas, 30 × 42 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, yes no yes no yes no yes no – dance, 2020, oil on canvas, 30 × 42 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

KH: I don't think I am saying 'yes' to all methods. For example, I wouldn't really dare to produce objects, but not because I'm not interested. I would have the feeling I’d just lose it totally. Like you say, there are already so many options, it's some kind of FOMO, almost. The main feeling is that I want to figure out what to say. There are so many great paintings and painters, and I know it is not really possible. But also, I don't want to repeat history so much. So maybe it's this desperate longing for creating something 'meaningful' (I hate this word), and producing like a maniac, somehow very exposed, somehow hiding in the studio, gives me hope in this quest. VP: Do you know about the exploding cucumber? It is a plant which shoots its seeds around, in a weird way 'throwing into the world' reminded me of it. Spritzgurke! [caption id="attachment_72251" align="alignnone" width="660"]

Vika Prokopaviciute

Vika ProkopaviciutePale Grey Brush Fire, 2020

200 x 130 cm, oil on linen[/caption] [caption id="attachment_72252" align="alignnone" width="660"]

Multiplying Pale Brush Fire, 2020

Multiplying Pale Brush Fire, 2020200 x 130 cm, oil on linen[/caption]

KH: Oh yes, we always fancied exploding them with our fingers as children, and still up to now. I imagined it would be an actual cucumber which is exploding when it's 'grown up'. I have to paint that. Also, when I think about your paintings, it's not so much that they are exploding, but continuously spritzing (not actually true, it's more splashing and flowing, but I like the relation to the German word), like an endless application of colour that doesn’t stop from one painting to the other, but just changes. And even though you would often say 'no' and sometimes say 'yes', for me it's so important to see the whole action. Maybe for me, it's a bit like the contrast to that, it's more 'stop and go'. Although I can totally relate to what you said about each painting being the answer to the last one. VP: Do you mean like 'stop and go' and move to the next one? Kiss-and-ride! I see it in your small-format paintings on cardboard. They are more like vessels and more pronounced as portraits or still lifes, for example. Large-format paintings are multi-functional in a way: a still life is not only a still life but also a portrait and a landscape. What was the difference in the process? [caption id="attachment_72271" align="alignnone" width="660"]

Katharina Höglinger, On a Plate, 2020, oil on cardboard, 27 × 36 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, On a Plate, 2020, oil on cardboard, 27 × 36 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_72276" align="alignnone" width="660"]

Katharina Höglinger, Self-Portrait in the Woods, 2020, oil on cardboard, 27 × 36 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, Self-Portrait in the Woods, 2020, oil on cardboard, 27 × 36 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

KH: There is a certain amount of energy in one painting, and, until now, I have never managed to have different amounts in different sizes — metaphorically speaking, because I would not be able to measure it. So, with tiny formats, it gets very condensed while with large formats, it almost feels like loosening the canvas, particularly with unstretched ones. I have the feeling your amount of 'energy' (it's not the right word maybe) is more exponential with size. VP: Small-formats weigh the same as large-formats. Reminds me of 'What's heavier? A kilogram of steel, or a kilogram of feathers?'. Maybe it has something to do with scale, the focus distance. I try to keep this distance more or less the same. You know, I paint sometimes large formats with the same brushes as small formats, even big parts. It gives me the feeling that 'I did my job', put enough labour into it. Weird, haha. And the scale stays the same. KH: So in that sense, your paintings have their own weight, like a kilogram of Vika Prokopaviciute Painting. You create your own measurement. VP: Or one joule of Katharina Höglinger Painting, if we talk about energy. KH: I paint every format and every surface with different brushes, colours, technique and focus distance. Using lots of different materials is a huge interest of mine. Here we are again: it's that matter of different decisions or options. VP: In 'Being Ecological', Timothy Morton says that the whole is always less than the sum of its parts, although we used to think the other way around. It can be also about painting. In painting, feathers can be heavier as steel. This makes me think about gravity and your '(purgatory)'. It looks like you turned the canvas, but once you explained you didn't. I like to feel fooled in this case. [caption id="attachment_72280" align="alignnone" width="660"]

Katharina Höglinger, (purgatory), 2020, oil on canvas, 90 × 110 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, (purgatory), 2020, oil on canvas, 90 × 110 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

KH: 'Gestalt psychology argues that the whole is different than its parts, not greater than ...' I like this idea of equalizing. For me, it is a way to deal with the uncountable, the endless amount of paintings which are produced, which are situated in and come from different scenes, different circles, different environments, different ages, different motivations, different urges. There is this great talk by Amy Sillman, where she speaks about drawing in the continuous present. She shows a slideshow with drawings, and to each of those drawings, she adds a verb that shows how democratic the process of drawing is. I would go further and say with painting it's almost the same. She shows all these works by those famous people without mentioning their names, which I borrowed when I did a public talk amongst painters with an open discussion called 'Painting and the self & itself'. I played a slideshow with a mix of paintings related to the topic by my Viennese colleagues, old masters, famous painters, outsider artists, my daughter and myself. And people in the audience did not know about it, and some saw their paintings. It’s this kind of equalizing that I like a lot. But to equalize that also makes me feel very anxious about being a professional painter. And then I think of musicians and writers: from this distance, I can understand that it is altogether important. So back into the loop! VP: Equalizing would mean moving towards the non-binary. Like Amy Sillman says that stating that drawing is a pre-painting would be wrong, although it shows the intelligence of the first. Drawing is refusing the logic of primary and secondary. I start with a drawing and later create the surface out of it, filling it with paint. Painting becomes a surface between the lines. Or I would 'paint' a line like I would paint a wire or a ribbon. Is there a difference for you between drawing and painting? KH: I know what I would call drawing and what I would call painting. I make a difference in using these terms, but definitely not in values. A two-minutes tiny drawing can be as strong as a two-months huge painting. Drawing for me is: creating motives, focusing on the narrative, putting lines in conversation, creating tension. But it doesn't necessarily mean that you can't use (liquid) colour. Painting is more about texture, light, space and effect and of course, how colours work and behave. VP: It fits the idea that you put the same amount of energy in your paintings, equalizing hand-drawn gloves and big-formats, dissolving one substance in another one until the borders are disappearing. Also inviting other artists to participate in this process: for example, Lena Sieder-Semlitsch, who created the storage table for your T-shirt book. The table is like a transformed painting — wood and canvas support your book, and it becomes more potent having such a display. Also, it reminds me of the pochade box, the one plein-air artists use as an easel and to store their supplies. [caption id="attachment_72267" align="alignnone" width="660"]

Katharina Höglinger, The Secret Life of KH, 2019, oil, oil pastels, marker, paper, T-shirts, cotton gloves, poplar and pine wood, cotton fabric, velcro fastener (Storage table: design and construction – Lena Sieder-Semlitsch), 65 × 102 × 76 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, The Secret Life of KH, 2019, oil, oil pastels, marker, paper, T-shirts, cotton gloves, poplar and pine wood, cotton fabric, velcro fastener (Storage table: design and construction – Lena Sieder-Semlitsch), 65 × 102 × 76 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

KH: At this point, a super big thanks to Lena Sieder-Semlitsch. She built the display, table and transport solution for my hand-painted artist book 'The Secret Life of KH'. Lena is working a lot at the interface between transportable kiosk and sculpture. When I asked her to build a box for the book, we came up with the idea of the box that was a table and also a suitcase. She used Molino for the padding, making the whole thing referential on so many layers. As you said, it reminds of a pochade box, and people keep adding pasting table. You know that Seinfeld episode, where Kramer made this coffee table book: 'If you don't have a coffee table, it turns into a coffee table.' VP: Maybe all these endless options free you from tags, claims, expectations. Inventing, sometimes reinventing, 'producing like a maniac', being too much, surprising yourself and the audience equals explaining yourself (to yourself?), being insecure in front of others, being vulnerable. And by not keeping it safe you find comfort in it. You mentioned in the beginning 'salvaging' the work. Rescuing it from the void by producing it and then letting it go, offering its vulnerability to others? To me this is a very pronounced characteristic of your works: they are inclusive and inviting. All these faces, vases, flowers, dogs, windows, lips, hands and feet, surfaces and textures are openly speaking to the one who is looking at them. KH: Also in a very literal way, salvaging the object from collecting dust in storage. I don't have this kind of relationship with my paintings which would not allow me to separate from them. But at the same time, it also feels like I have a responsibility. VP: Grown-up paintings, finally leaving the studio. I feel frustration sometimes to see paintings performing strangely in the exhibition. As if they are at a formal dinner where they act polite and watch what they (you) say, being aware of the context. Losing tongue, right? Perhaps they are more 'honest' at the studio. Here I see resistance: the unstretched 'Untitled' states its space, refusing to be a 'proper' painting; the museum gloves for 'The Secret Life of KH' play the art-handling game but, at the same time, they become a drawing object, too. How do you 'adapt' the surroundings for them? KH:I see that with your paintings and what you mean, but also, I really love when a painting goes to an exhibition or a wall somewhere in a living room or a showroom. They can say much more and fully unfold, which in a tiny and crowded studio like mine is maybe much more difficult. There is resistance, refusal, defiance and the ambiguous (and maybe essential for survival and mental health) urge to please. There is no difference in their values, all objects are supporting each other. I just had a super important term added to my describing vocabulary. I was listening to the Deep Color podcast by Joseph Hart, and in the latest episode he was talking toCurtis Talwst Santiago, whom I admire a lot. In this conversation, one of them brought up 'intuition as a tool'. This is very important to me, and until now, I was never able to put it right with words. Sometimes we tend to think of intuition as something we can't control. But intuition is something you can use and apply decisively. It is not something intangible; we can use it as consciously and strongly as our brains or our hands. And all the things mentioned above are parts of this interplay. VP: Perhaps this interplay makes them seem to be in progress as if they are changing (are being painted) in front of my eyes, right here. 'Untitled', the large-format unstretched painting is transforming every time I look at it. It hugs itself, then it holds itself on the wall, and the next second, suddenly, a boxing glove appears. How do you deal with its constant developing? Do you control it or take its offer? [caption id="attachment_72268" align="alignnone" width="660"]

Katharina Höglinger, Untitled, 2020, oil, acrylic and marker on linen, 164 × 182 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, Untitled, 2020, oil, acrylic and marker on linen, 164 × 182 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

KH: Maybe I answer with a photo story I just screenshotted from thisLee Krasner interview:

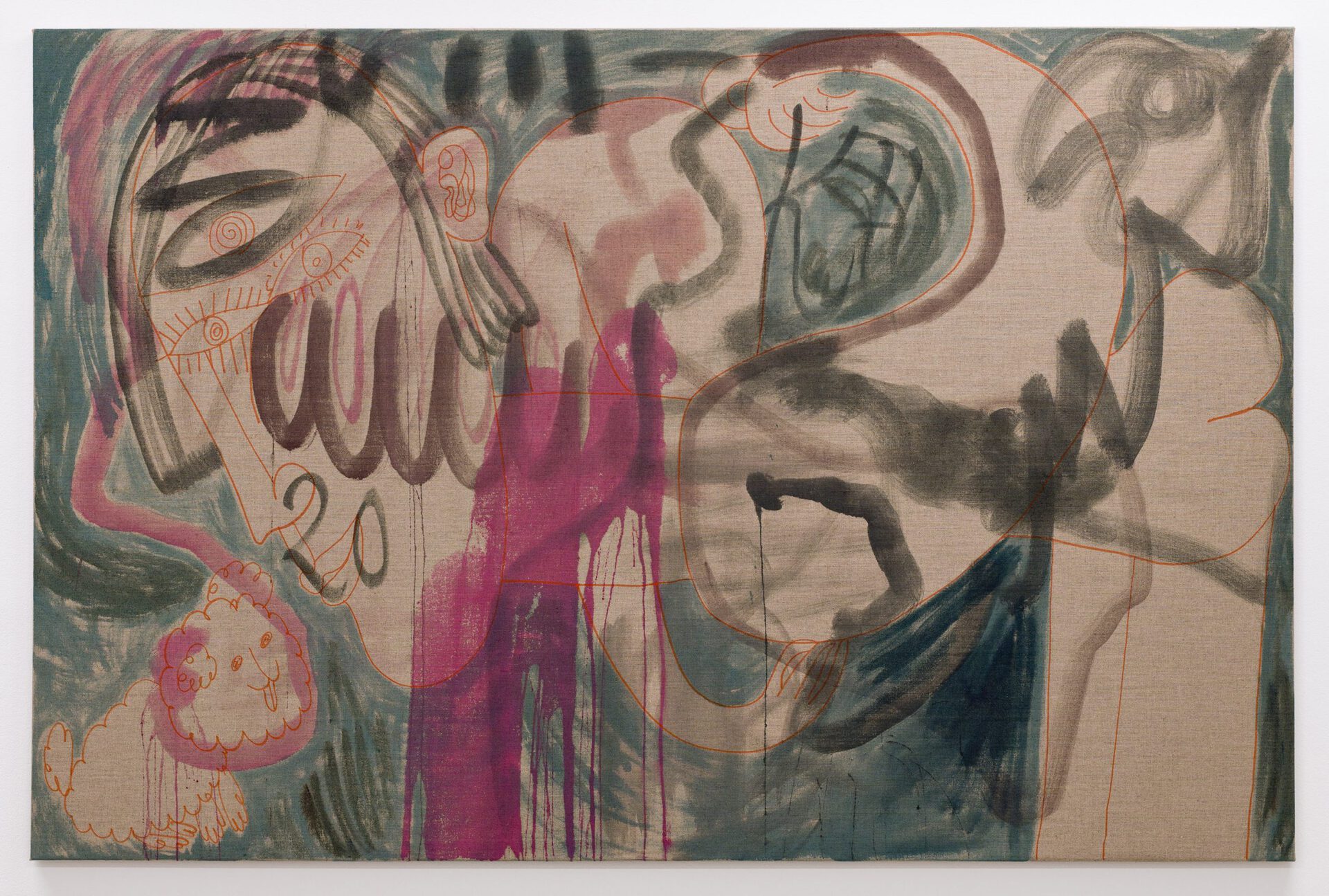

VP: We talked once about painting problems, and there was your painting '(vanitas)', which you painted over several times, adding more elements, merging faces. And we were like: 'Where is the problem?' It was clear that you, exactly you, would mix a lot of things, creating a strange dreamy mass of all possible techniques and materials (options again!). But you were more concerned about the opposite ones ('Bad Flower' and 'Hello Darling'), so light and so easy like you didn't expect it from yourself. Usually, one would be afraid to stop too late, but in this case, it was another way around: 'why would we want to do the least'. Does it make sense? [caption id="attachment_72265" align="alignnone" width="660"]

Katharina Höglinger, (vanitas), 2020, oil on canvas, 85 × 70 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, (vanitas), 2020, oil on canvas, 85 × 70 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_72266" align="alignnone" width="660"]

Katharina Höglinger, Hello Darling, 2020, fabric paint and marker on linen, 124 × 190 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi

Katharina Höglinger, Hello Darling, 2020, fabric paint and marker on linen, 124 × 190 cm, © WONNERTH DEJACO and the artist 2020, photo: Peter Mochi[/caption]

KH: It does. But what makes no sense and also always, of course, surprises people, because nobody would ever expect that from my work anyway, is that from time to time I'm really struggling with what one calls 'the style of a painter'. And then I have a feeling I should find one style or in the end, one thing, will develop it, but I'm just not there yet. Also, people keep saying things like 'Oh, now eventually it all comes together' or 'I'm curious where this all leads to in the end' and I'm wondering: Is it like this, does it have to be like this, am I just lying to myself and I'm just not 'there'? But in the end, creating 'a style' is just not what my work is about. It's about something else and if I need to put it like this, that's a style, too. VP: Then I ask you the question inspired from a recent 'Talk Art' episode with Tracey Emin. Are you afraid sometimes of what you paint, of what you see? I guess it is not so much about fear but about perceiving yourself through the eyes of the audience. KH: I am afraid only when it is about frightening stories. But then it is more about being afraid of the topics themselves, not so much of the painting, and I am not so sure if I should show it to an audience. For example, after the terror attack, I made some watercolours which just freaked me out — I didn't do them on purpose. I was like: 'No, that can't be in your painting' (even though it was just abstract watercolours, I don't think anyone would have noticed, but the feelings I had were just too frightening for everything). The other thing, uncanniness, is very important to me, although sometimes, of course, a bit adventurous. It can happen that I deeply hate my painting, I really would love to cut it, burn it, paint it over or whatever, but then there is the same amount of love too, and that's where all the evolvement for the future paintings can happen. '(purgatory)' is one of those paintings, it's a bit too much of everything, and that's why I like it every day a bit more. Speaking of Tracey Emin, her work is different as she was always using autobiographical elements. People keep saying that about my work, too, but in my case, it is more the illusion of autobiography. I don't think one might know a lot about me by just seeing my painting. It's more like construction and deconstruction of roles, identities and expectations. I made this painting in 2018 with the title 'My heart is a clock, you think you know me. You don't': [caption id="attachment_72250" align="alignnone" width="660"]

Katharina Höglinger, My heart is a clock, you think you know me. you don´t, 2018, acrylic & oil pastel on canvas, 14 x 18cm

[/caption]

Katharina Höglinger, My heart is a clock, you think you know me. you don´t, 2018, acrylic & oil pastel on canvas, 14 x 18cm

[/caption]