Archive

2020

KubaParis

Luleå Biennial: Time on earth

Location

Norrbottens museumDate

20.11 –13.02.2021Curator

Karin Bähler Lavér, Emily Fahlén and Asrin HaidariPhotography

Thomas HäménSubheadline

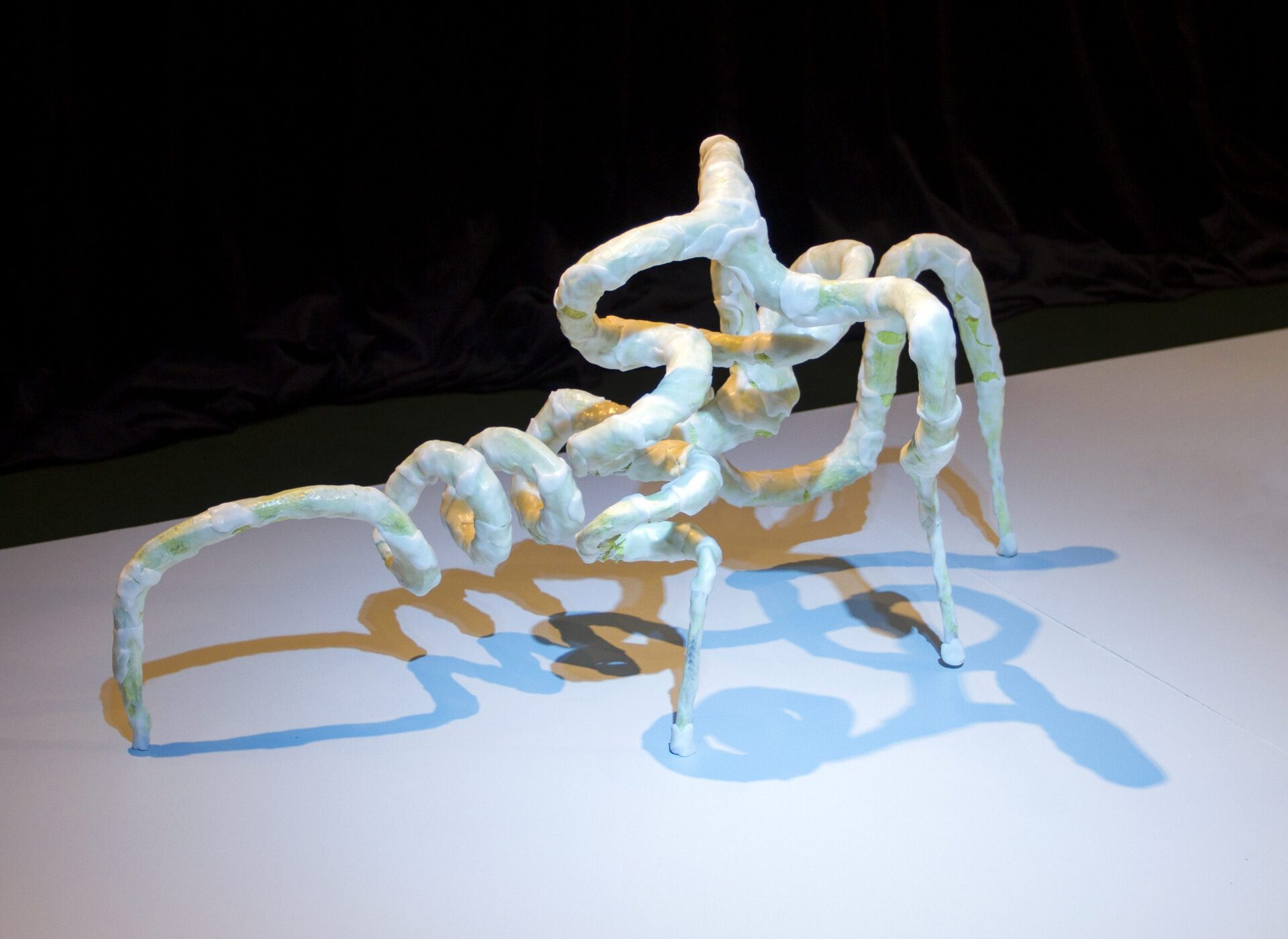

Erik Thörnqvist works with various fictional, historical, collective and personal references to explore affective states, labour and how bodies define space. His work is time based as well as spatial – a fictional and experience-based universe that only emerges gradually. Through an encyclopaedic yet quasi-scientific approach, Thörnqvist’s installations explore concepts such as authenticity and objectivity. For the biennial, he has produced the new works, Cartesian Crawler, on view at Luleå konsthall, and Big Science, Small Country at Norbotten’s Museum.Text

In the installation Big Science, Small Country, Thörnqvist revisits the evacuation route his grandfather helped construct as part of the Esrange Space Center in the 1960s. North of Övre Soppero, o the E45 motorway, this gravel road extends even further into remoteness towards “Crash-zone B”, the area where possible space debris was intended to crash, disregarding the Sami villages located there for the winter.

Through his grandfather’s gaze, Thörnqvist portrays an infrastructural project implicated both in the arms race of the Cold War, and in the wider project of earthly as well as planetary expansion. The work asks questions about the existential consequences that follow in the wake of technological progress.

Sound: Robin Rådenman

8mm film: Karl-Erik Thörnqvist

This cartesian crawler is a fabulous creature, a phantom that originates from and is generated in Crash-zone B. It can move freely over the horizontal x and the vertical y-axis; it is an agent of the in-between. The sculpture copies the dimensions of the shelters that line the road in Crash-zone B (that is discussed in Thörnqvist’s installation at Norrbotten’s museum). Cartesian Crawler’s presence stirs a number of complex and political issues related to place, cultural heritage, colonialism and acceleration. The freewheeling exponential growth of our time, whereby we live in constant oscillation between utopia and dystopia, resemble classical and religious notions of history as steering towards inevitable catastrophe and extinction. Perhaps the crawling and clambering will pave the way for a different reality altogether.

The Luleå Biennial stretches across the vast region of Norrbotten. Budding into the arctic circle at Sweden’s border to Finland, the region – with its heavy industries, mining landscapes, high-tech research centers, unique nature and the historical homeland of the Sami people, Sapmi – plays host to one of the world’s northernmost art events. This time, the biennial will take place in Luleå, Boden, Malmberget, Storforsen, Arjeplog and Korpilombolo – in an evacuated school, in a church, at a silver museum, at art centers, in a former prison and at Norrbotten’s Regional Museum.

The Luleå Biennial is an international biennial for contemporary art where global and hyper-local perspectives come together in site-specific installations. Alongside of numerous exhibitions, the 2020 edition will also include a touring literature program, theatre, radio and an online journal. The 2020 Luleå Biennial grapples with the question of what ”realism” could mean today both as a concept, expression and paradigm. Through their works, the invited artists tell of realities related to society as a system – bureaucracy and logics of mass media and industrial infrastructure – but they also break into, challenge and topple these reigning arrangements; through strikes, the psyche, theatre, magic and, not least, art itself. Realism emerged as an art historical concept in the second half of the 19th century and remained prominent into the first half of the 20th. This multifarious project grew out of a general interest in portraying society as it actually appeared in all its roughness and mundanity and injustice. On the one hand, realism pro-posed a set of aesthetic conventions, but more than that it meant the introduction of a new world of motifs to art. The realistic project was initially led by an intellectual bourgeoisie, but would since come to involve art and literature in which the working class asserted itself as both topic and agent. With its more blatant political edge, this later period is often referred to as social realism or socialist realism.

Karin Bähler Lavér, Emily Fahlén and Asrin Haidari