Archive

2021

KubaParis

bubble, but

Location

Jakob ForsterDate

25.11 –18.12.2021Subheadline

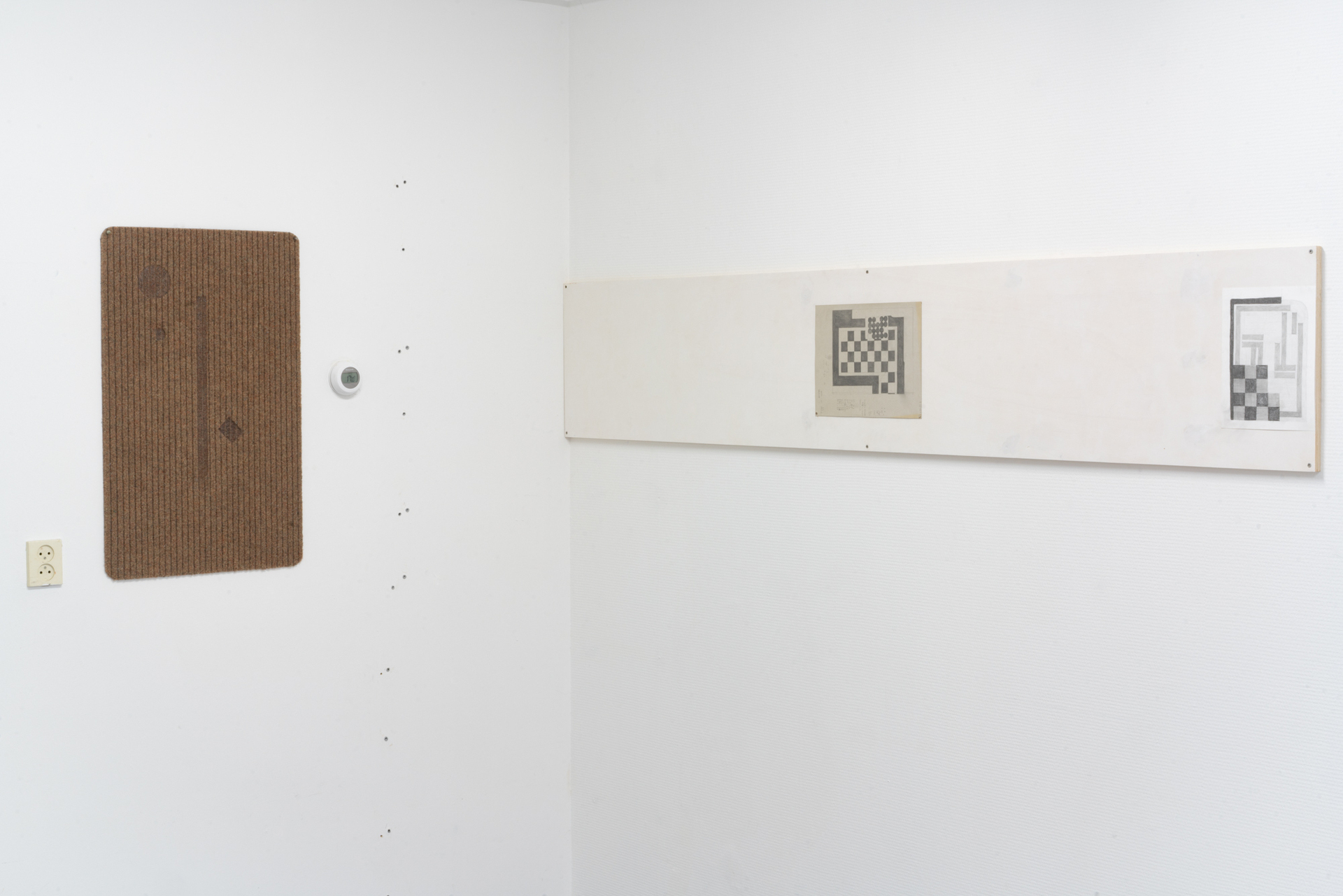

solo presentation of Jakob Forster at Jakob Forster, Rotterdam third and last exhibition in the spaceText

Яeflections

A text by Isabelle Sully

I am writing this text at an airport, in a city that I have been temporarily

stranded in, waiting for a flight that is not taking me home. Therefore, let’s begin with the premise that the doormat lying at the threshold of my Air BnB ‘welcom(ing m)e home’ is an abstraction. The artist on whom this text reflects, Jakob Forster, tells me that he wants an art historical t¬ext about a new body of works made from doormats, tells me that he hasn’t had one written about his work before, tells me I seem to be able to perform many voices. They say in English that you are a doormat if you let people walk all over you, wiping their feet on your face without any concern. Maybe Forster’s observation makes me a doormat, a doormat in the form of a writer, who performs whatever voice requested on command.

This is not as existential as it sounds. It’s an exercise in making myself at home in a text, something that Forster’s works have also had to do: make themselves at home in his apartment, while at the same time retaining enough of an intentionality to not disappear into the decor entirely. In his case the decor is his living room, in mine it’s this page. Do you see what I mean here? If not, what I am trying to convey is this: I am not at home in the art historical. Forster’s works are not at home in his apartment, and I am sure he is not necessarily at home in it either. If so, he wouldn’t have turned his living room into a gallery. He would be doing what the name infers: living in it. But while I may not be at home in the art historical, Forster’s works not at home in his apartment, both myself and the works are able to give off that impression, if we wish. In the end, the deflection of appearance, inherent to surface, is largely the point.

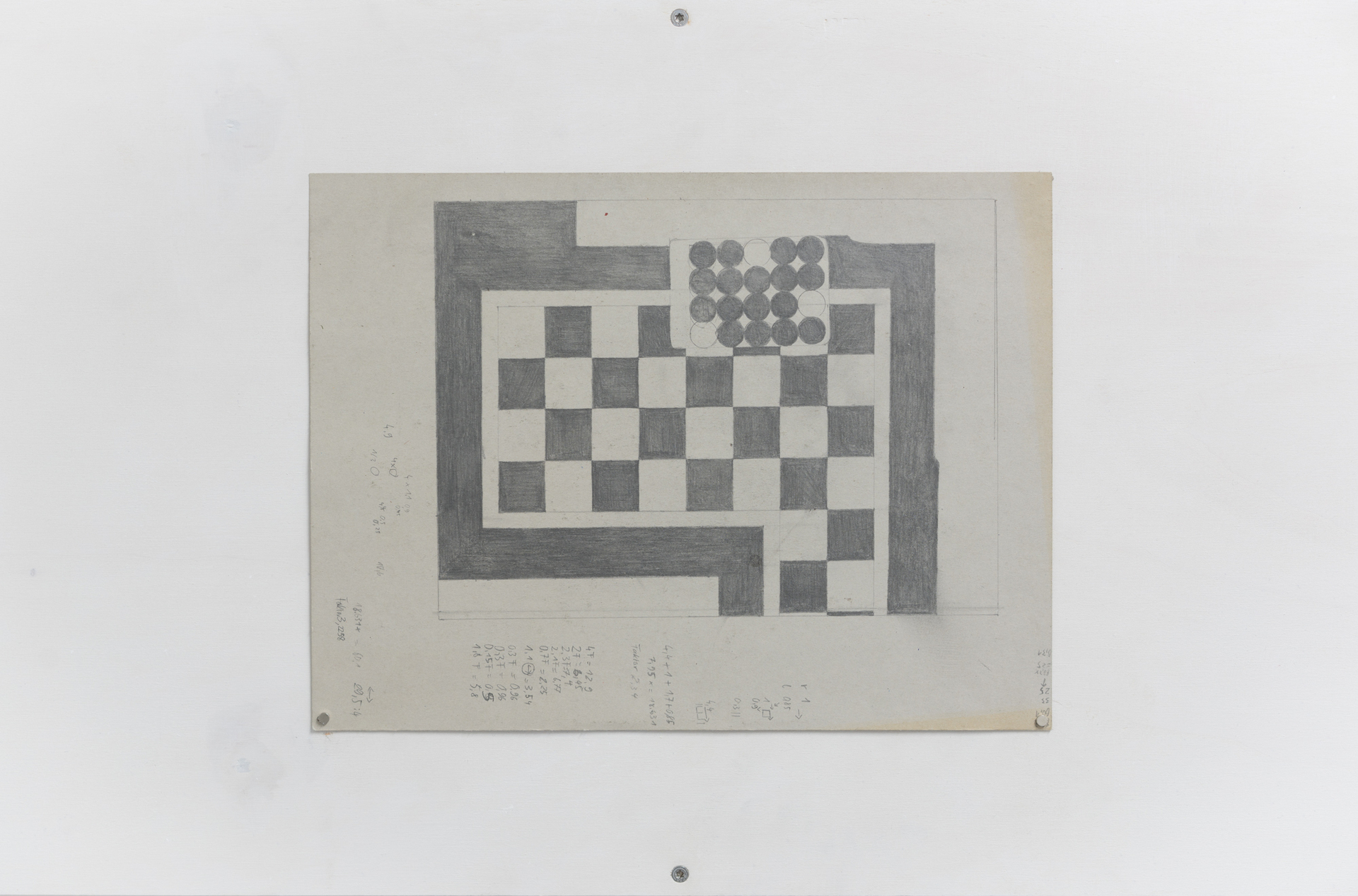

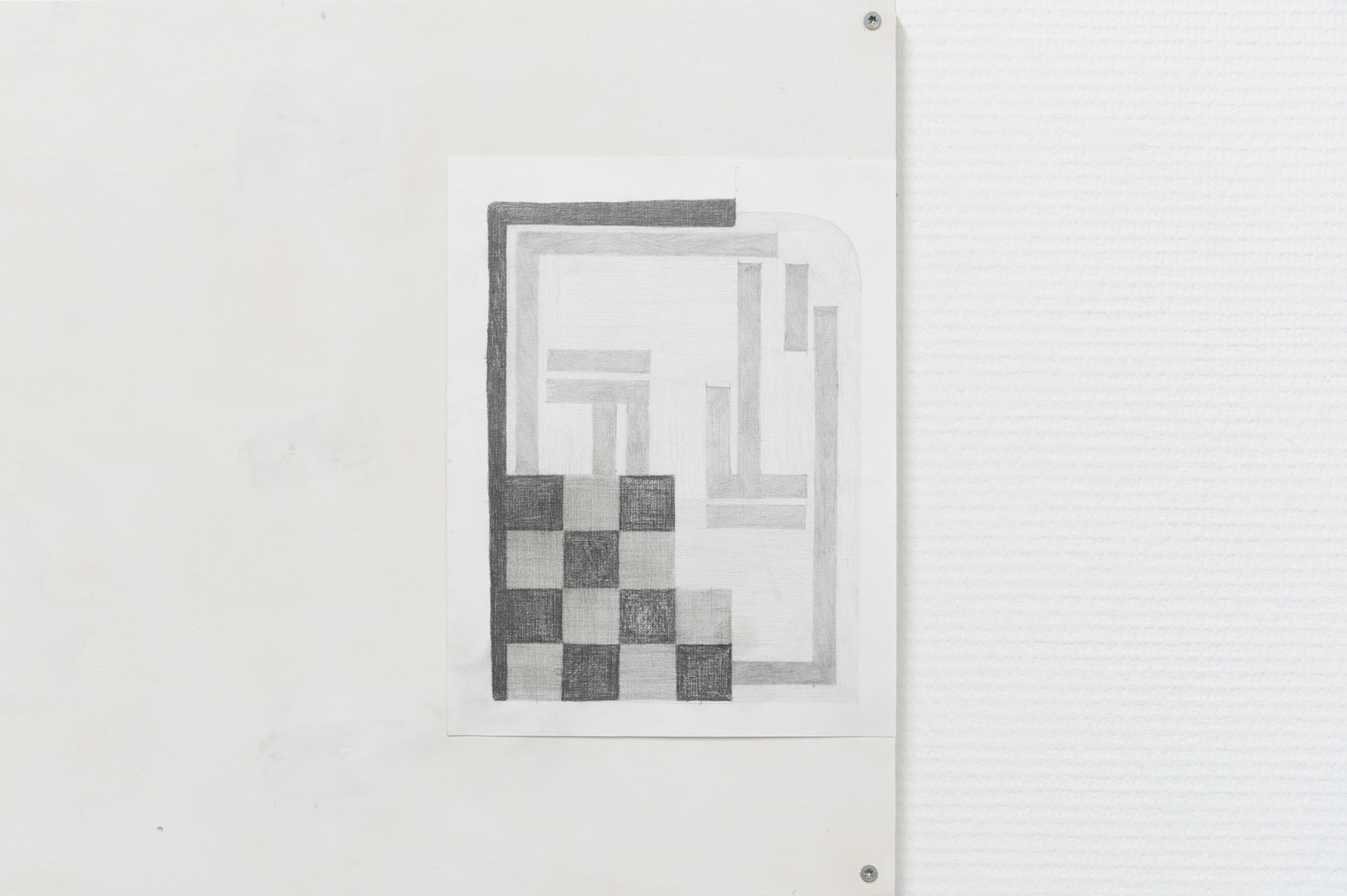

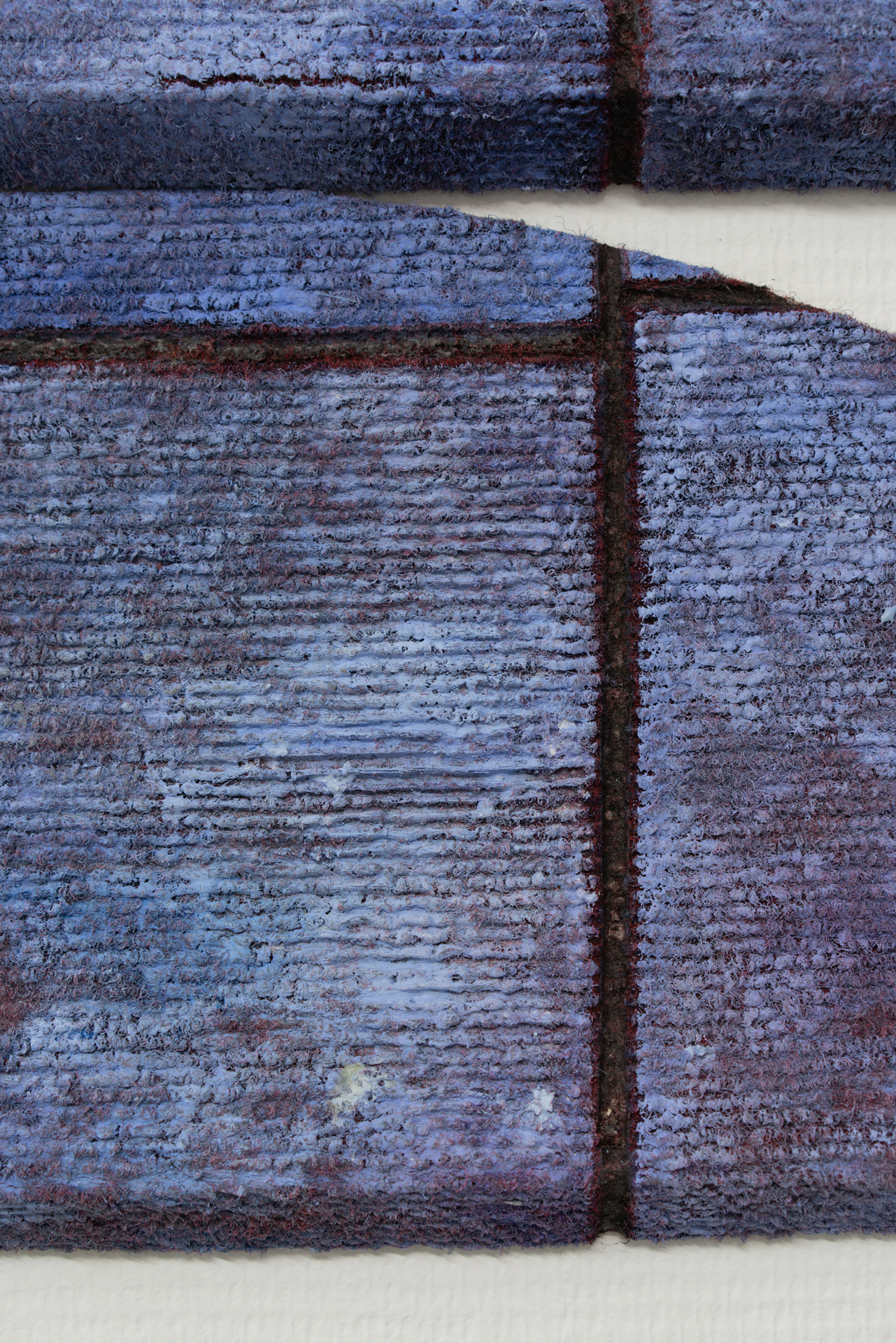

This text is art historical as far as I understand it, in that it was informed by looking at a set of works repeatedly, contextualising them across the material gathered during a studio visit and now serving the informational urge a viewer might have to understand more about from where these works sprung. It’s all just a matter of perception. Yet in keeping up appearances, in a more standard art historical text one might reflect upon Forster’s use of layered two-dimensional planes in ‘A quick burn‘s slow recovery... (2021)’, on the development of the adapted readymade as it operates within twenty-first century art making in ‘Twenty masterchefs... (2021)’, and thus on his situatedness within a history of German abstraction (see further: ‘A sack of golden... [2021]’). And one might do so in terms that one might associate with art historical posturing, yet one will not.

I will, however, reflect on the interplay of images at work in this exhibition in terms that seem casual enough to betray the friendship currently developing

between myself and Forster, a subtle nod to an intimacy warranted by the fact

that we are, after all, in his living room. One of said images is the ‘press image’ for the exhibition, which depicts Forster and a friend(?) sitting in his studio, which is, also, his gallery. Forster is taking a photo of the pair with his phone, evident because the resulting image is the reflection of them doing so in the window in front. Mediated by two reflective surfaces (the window and the phone screen), this rather informal, nonchalant image (in the scheme of ‘press images’) does in one, perhaps improvised instance what bubble, but does across the five works in the exhibition: it reveals the mechanics of mirage. That is, with surface layer upon surface layer, or reflection upon reflection, the image becomes a multiplication of projections, ones that attempt to deflect but which ultimately result in a blatant illusion.

When thinking about two-dimensionality it also feels natural to gravitate

towards its outer fringes, towards the edge of the plane. Each of the works on

display are self-contained in that they have borders built in, which ultimately act like a frame. While this is itself not an illusion, the self-containment does refer back to the title, which carries the word ‘bubble’ as, to quote Forster, a reference to ‘chosen oblivion as an attitude.’ In the end, we all live in our own bubbles, which at their core operate on the contradiction of safety (we feel at home in our bubble) and containment (we are limited by its borders). As a surface, the doormat is not so dissimilar in function: a swatch of rubber and nylon primed for safely removing dirt from shoes so as not to contain the borders between inside and out.

As for the later half of the title‘, but’ conventionally operates as a qualifier. ‘He’s nice, but...’or, alternatively, an excuse: ‘I did the assignment, but I just forgot to bring it.’ And, in its worst instances, ‘, but’ operates as a negation: ‘I’m not a racist, but...’ Coupled together, ‘chosen oblivion’ + ‘, but it’s not that simple,’ I can’t help but think of Munich—a city that Forster and I have both spent time in in different capacities, one that, I presume, was a catalyst for me writing this text. For an exhibition of works made on, with and around found doormats—the welcoming gesture latent at the threshold of the home—the city is an all-too-obvious point of reference: it is where Foster was born. This acts as an historical qualifier for this art historical text, as growing up in that environment feels key to the work. Munich is the city of a thousand mirages. For one, it famously built a complete replica of the Parthenon, repackaging it as its own attraction. Following the Second World War, it was also meticulously rebuilt to look exactly as it did before 1940, fascist architecture and all, and even now there is a layer of denial blanketing the city, it’s SS history hidden in plain sight.

Forster’s work ‘Bitter strong and so .... (2021)’ most notably characterises the defilement ironically present in this quest for purity of surface. The doormat in this work remains largely unaltered, aside from the imprint of the rim of a hot coffee pot melted into the surface. Forster told me that once he mistakenly discovered this technique, he began replicating it in other works. In this small accidental detail of life simply happening alongside the production, reproduction and replication of works of art, decidedly keeping it in the exhibition, choosing to focus in on it rather than discarding it or erasing it through restoration, Forster shows that, just like architecture, it’s all just a façade. But rather than delving deeper, trying to get below the surface, it instead becomes a base itself. A kept up appearance, sure, but also a foundation on which to inscribe anew.

Isabelle Sully