Archive

2021

KubaParis

BURNED AGAINST THE REAR FENDER

Location

Lehmann+Silva gallery, PortoDate

11.04 –08.06.2021Photography

Dinis SantosText

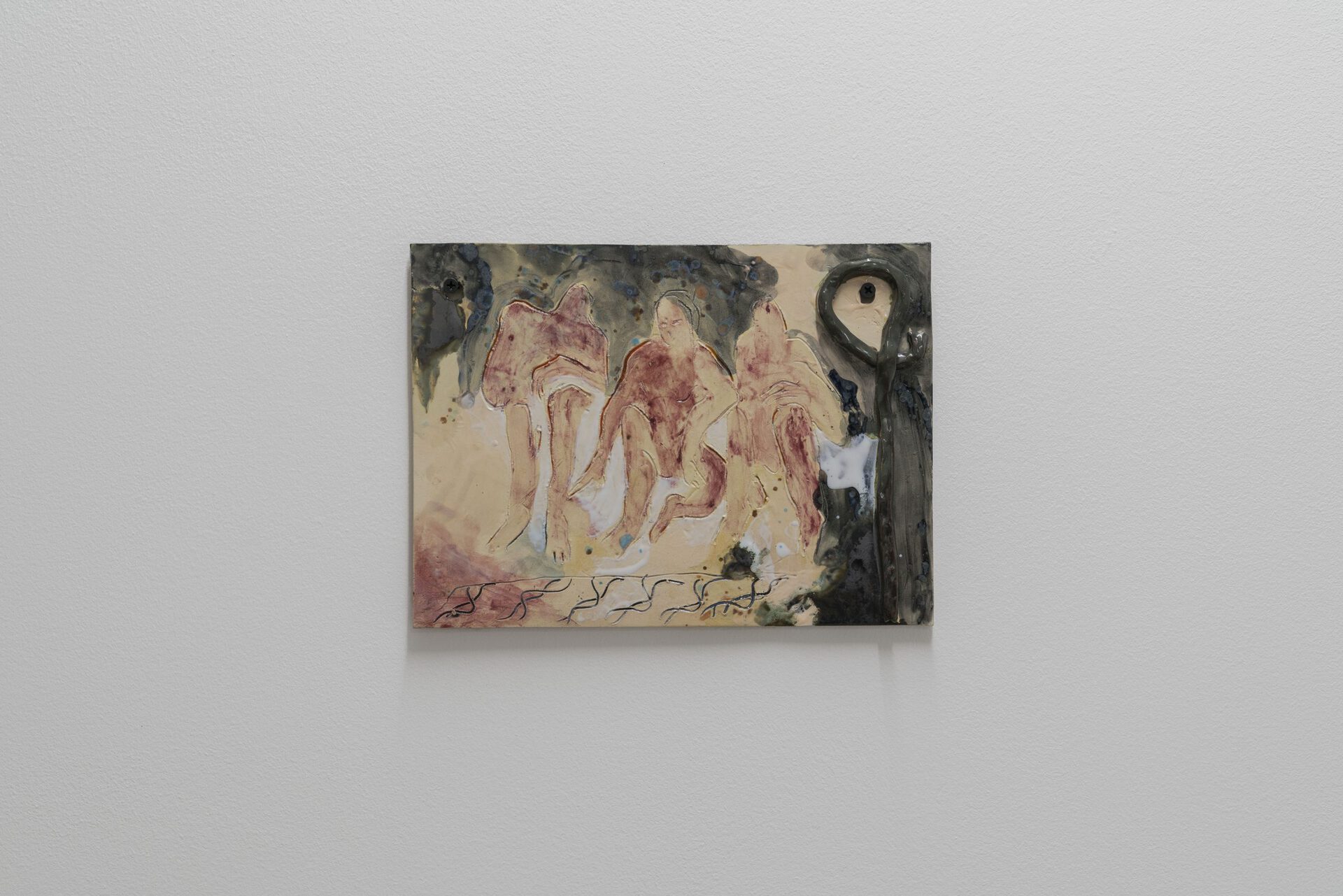

Burned against the rear fender, Monika Grabuschnigg’s first solo show in Portugal, continues her investigations into bodily and cerebral desire; into the ravaging force of fire and intensifying heat across the planet; into what the inexorable melding of cognition and code means for what it is to be conscious.

The works impel us, drag us as if paralyzed, through an otherworldly but uncannily recognizable landscape: we know this place, even as it unsettles us deeply. As we move amongst them, the pieces encroach, snag, and rip through the lines that delineate human from non–, inviting us to lose ourselves in that vertiginously euphoric moment before a fall; or to dervish through the ash piles and micro-plastic mountains accumulating around us: acne blooming across on the already scarred surface of the Earth. The shattered and annealed surfaces of her works mirror and break our own uncertain edges, the delineations we sometimes kid ourselves are certain.

Fiercely materialistic, densely detailed, textured with as much fine precision and pristine accident as the terraforming that will define our post-Earth futures, Grabuschnigg’s works can be read with either micro-attention or macro-fascination.

To lean in to the star-spattered, 1050-degree-scorched dribbles and explosions of glazes on the hanging reliefs like Drunk on loneliness (2020) is to be sucked through an airlock into your last few gasps beholding a gaseous nebula, dangled before all those warnings from 14 billion years ago about what happens when you play with creation.

Step backwards, flip the usual gravity, birds-eye yourself in front of the same works, and you see the tectonic plates of the supercontinent Pangaea, from which our seven continental units split and drifted apart from millions of years ago; or a river running through a medieval mappa mundi: a cartography of our pre-cyborgian turn, our post-Copernican leap.

In the scorched and melted sandals we again see Grabuschnigg’s compulsion towards fire. These disfigured and defiled vestiges of a consumptive society that has scorched itself into oblivion are both recognisable and repulsive, reassuring and terrifying; as eerily familiar as lava-encrusted artefacts from Pompei. The extreme heat of ceramic techniques (fired in kilns hotter than the surface of our sun’s closest neighbor Mercury) ensure our minds cannot drift far from the raging forest fires surrounding our cities, the oil-bubbling carbon-cauldrons that are the pacemakers of our hyper-capitalist system. Clay is natural, dug from the ground, tactile, organic. So is oil. So are those ancient human sacrifices winched up from peat bogs and tar pits (see the work Glove puppet for the soul, 2020).

The common theory of free will is that it’s all about choice. We see possible futures diverge in (burning) yellow woods, then we choose one. We predict, we analyse, we choose. But that’s only one side of it. Just as often, the chronologically opposite is the case: free will comes from making – or falling into – a decision, and then reflecting on it. Judging, deciding: What have I done? What did we do wrong? How do we make it better?

Freud, Harraway and others have posited the idea of historical wounds to our sense of self: the Copernican, the Darwinian, the Freudian, the Cyborgian; four forks along the smouldering road that have changed our species, and our planet, forever. The decisions have already been made. The only question left, Grabuschnigg’s work seems to be telling us, is this: What, in order to remain human, are you going to do about it?

Martin Jackson, January 2021

Martin Jackson