Archive

2022

KubaParis

Dreaming Organs

Location

CrèvecœurDate

29.04 –03.06.2022Curator

Ernst Yohji JaegerPhotography

Aurélien MoleSubheadline

Audrey Gair, Wolfgang Matuschek, Hamada Yasuaki, curated by Ernst Yohji JaegerText

Dreaming Organs

Audrey Gair, Yasuaki Hamada, Wolfgang Matuschek

Curated by Ernst Yohji Jaeger

30.04. - 04.06.2022

Some time ago I had a studio in an old building on a factory site. On the way through the main gate to my workplace, I pass masses of huge black hoses. Through some of the open gates of the factory, I can see inside the large brick halls; mountains of stored hoses piled up, machines and people are working diligently. Two huge chimneys smoke nonstop and the factory produces day and night. I don’t know what this factory actually produces. I like this building and the semi-industrial periphery in which it is located. Especially the walks home after a long day of work through the factory grounds at night. At nighttime, they are almost festively brightly lit but I never see any people, just occasionally a dirty cat that roams between the black hoses. In the dark, they look like big intestines. The machines work and the towers smoke. But the machines seem to be more relaxed and the steam now is tainted in pink by the red warning lights of the factory. It seems to me as if the factory shows an intimate side at night and I feel as if the cat, the machines and I now share a secret.

*

The eyes provide living organisms with vision and the ability to receive and process visual detail. But it is only for brevity’s sake that we say we “see” at once a railway station at night. (1) The eye is an organ which hears and smells, which transmits heat and cold, which is attached to the brain and rouses the mind to discriminate and speculate. (2)

*

We say that something is strange when it defies reason, when we can’t find an explanation satisfying enough to stop wondering what it is. (3) Our very existence shelters mystery in the dull common place things we do all the time. When you repeat the same word more than 20 times, saying it out loud, you feel less and less that you actually know what it means. It’s also a question of how you perceive the world and the real on an every-day basis. The vividness inherent in the objects of our daily routines unfolds by de-familiarizing them.

Ernst Yohji Jaeger & Inga Charlotte Thiele

(1.) Virginia Woolf, The Sun and the Fish, p. 8, Damocle Edizioni, Venice 2017.

(2.) ibd.

(3.) J.F. Martel, Reality is Analog, Philosophizing with Stranger Things, available on https://www.metapsychosis.com

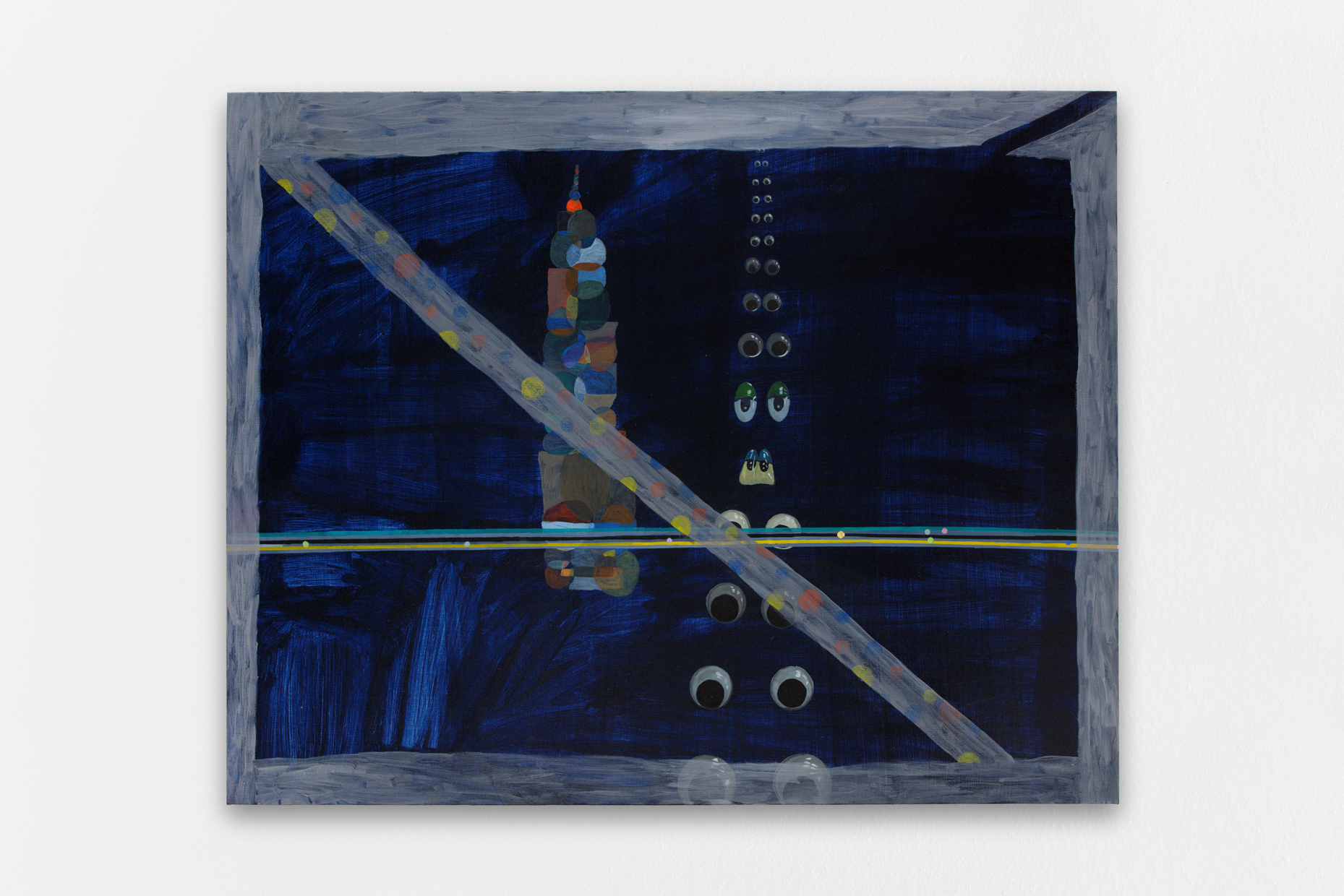

In Audrey Gair’s (born in 1992 in USA, lives and works in NYC) paintings colorful circles and geometric shapes condense into the New York city skyline, interiors and landscapes. Her everyday surroundings in the city are rendered and animated by the dots in different shapes and sizes. On her routes through the city, she collects words, impressions as well as objects such as stickers, hair clips or toys that cross her way, making them part of the paintings’ vocabulary. A mischievous game of hide and seek takes place and we, the viewers, are invited to participate in reveling in and succumbing to our bittersweet childhood recollections. Audrey’s paintings function as a theatrical stage for fragmentary narratives about individual and shared memory, the personal attachment to an oftentimes impersonal urban environment, and a dream-like, almost magical view on dwelling in and moving through a city’s infrastructure.

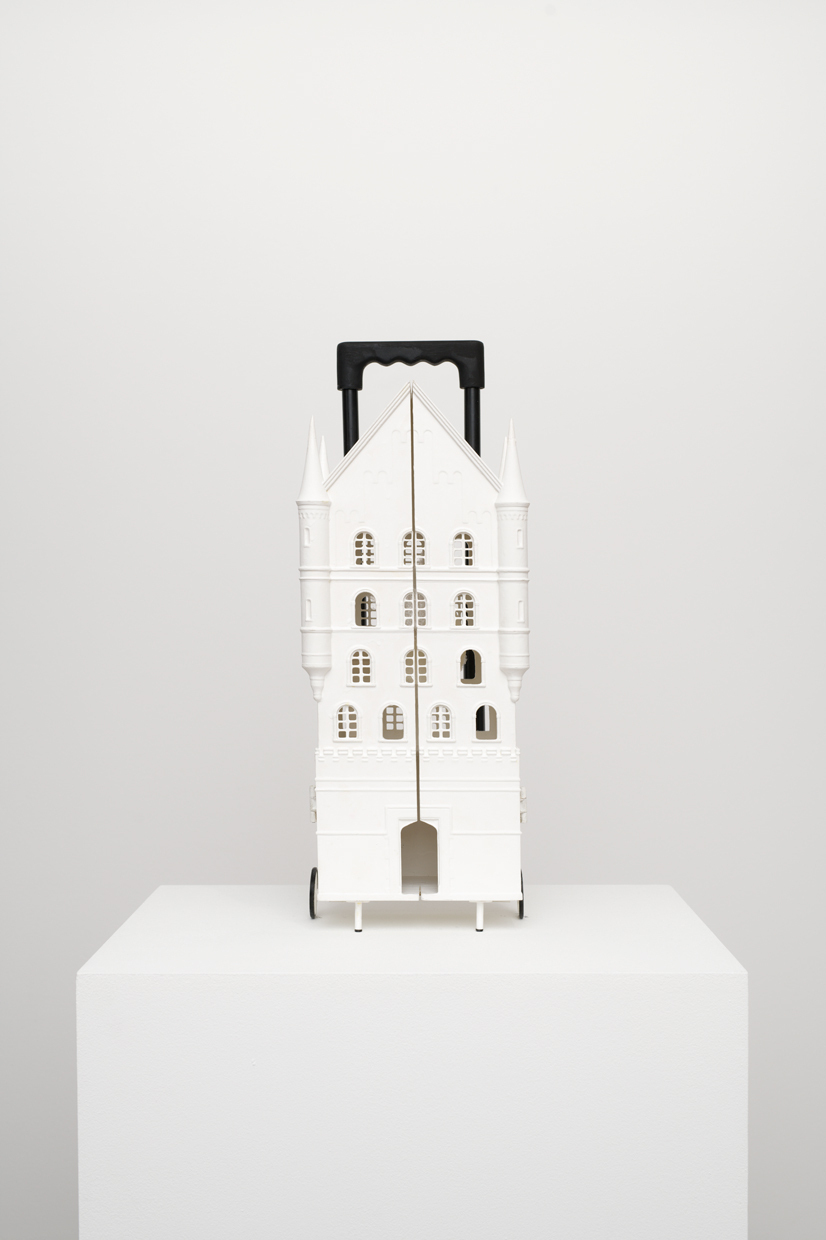

Hamada Yasuaki’s (born in 1988 in Japan, lives and works in Vienna) series of sculptures, titled Neighbours, is reminiscent of the Sylvanian family dollhouses made by the Japanese company Epoch. These toys, built in the shape of idyllic Victorian houses, are inhabited by cute anthropomorphized rodents which emulate a rural middle-class life set in North America. Hamada’s houses, however, are inspired by Neo-Gothic architecture and the interior is sparsely furnished and uninhabited. The trolley handle and wheels, which are attached to the houses, give them a fictional functionality and make them seem like a surreal readymade suspended between toy and commodity. Amongst other topics, Hamada wittily touches a variety of subjects through an aesthetic that stems from Japanese culture mimicking Western styles, creating new and curious genres. In Japan, clusters of row houses are constructed in an American/Victorian fashion. They seem to be made of wood or brick, but on closer inspection they turn out to be made of plastic. This architecture embodies the image of an ideal family but the faux material and copy-pastedness of these structures create a rather eerie and unsettling atmosphere. Hamada’s transportable miniature homes speak of dislocation, comfort and the burden that comes along with every home, be it the childhood or family home, or the home one moves to, tries to settle in and make in companionship.

Wolfgang Matuschek’s (born in 1989 in Austria, lives and works in Vienna) ink drawings depict nocturnal scenes, which seem to be witnessed casually, from the corner of the eye. There is no direct action taking place in the deserted, almost motionless environments that show industrial zones, construction sites, or unidentifiable city streets. The series in orange tones shows indoor scenes as if seen through a thicket, while the images drawn in purple ink are set outdoors. They share a quiet, intangible surrealism or supernaturalism. In contrast to the casualness of the scenes, the works are meticulously drawn, revealing highly sensitive compositions upon closer inspection. They tell stories about human-made worlds, technologies and infrastructures that have been left behind, as if all people disappeared without turning off the stove. The chimneys are still steaming but the dreamlike animals appearing in the otherwise empty architectures seem to be the only living beings that remain and possibly belong to these enigmatic non-places. Looking at the vacant sceneries, one might also wonder about possible activities taking place ‘next to’ the images presented to us: the drawings’ cartoony style points to a possible storyline being told but kept in secret from us.

Inga Charlotte Thiele and Ernst Yohji Jaeger