Archive

2021

KubaParis

EVERYTHING HURTS

Location

Bistro 21Date

01.12 –26.12.2021Photography

Anna Sophie KnoblochSubheadline

EVERYTHING HURTS consist in a multi disciplinary exhibition that reunites textiles works in large and medium sizes, sculptures done with upcycled taxidermies, concrete, steel and 3D print, as well as small size risography prints. The embroideries carry the rhythm of the narrative and extend like skins where – together with the taxidermies and sculptures – it is possible to follow an intimate story told stitch after stitch. With the repetitive action of sinking and lifting the needle, I slowly review my personal experiences, my lowest feelings: to reverse moments of vulnerability, to satisfy myself by treasuring violent memories.Text

Anal Abysmal / A rose is a hole is a…

by Domingo Martínez

The terrestrial globe is covered with volcanoes, which serve as its anus.

Although this globe eats nothing, it often violently ejects the contents of its entrails.

(…) Love, then, screams in my own throat.

Georges Bataille, L'anus solaire

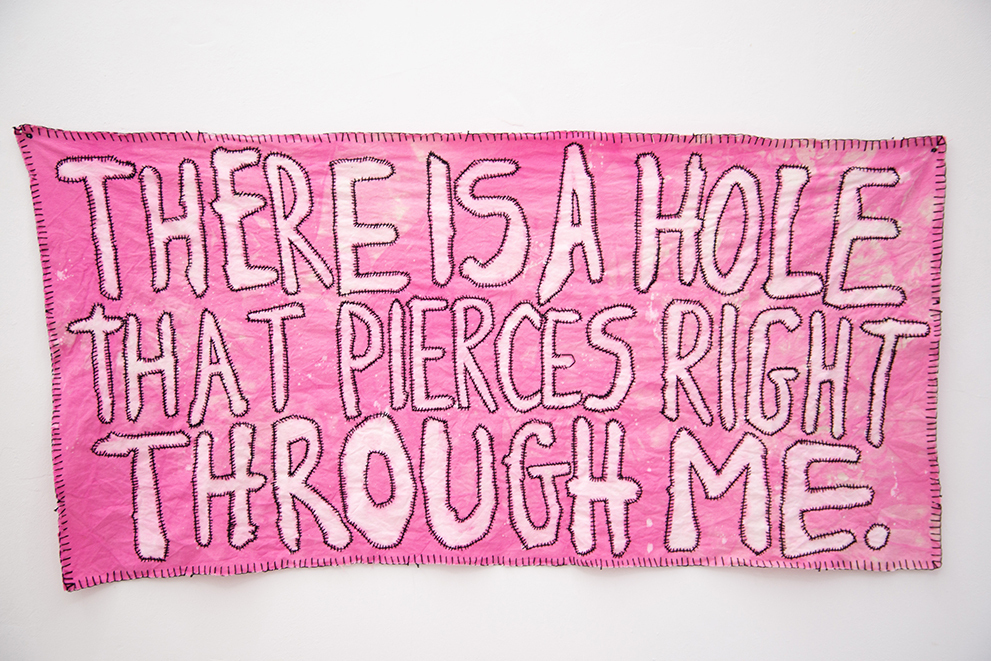

In the second volume of his book Spheres, Sloterdijk complained about a humanism (i.e., mainstream philosophy) bent on the impossibility of overcoming the difference between mouth and anus (I quote from memory, chapter is titled Autocoprophagy), between what is expelled and what is swallowed. I remembered this in regard to the work I wish you would kiss me like you eat my ass — asking myself if an anus can kiss like a mouth, and whether the anus is a second mouth and the mouth a second anus.

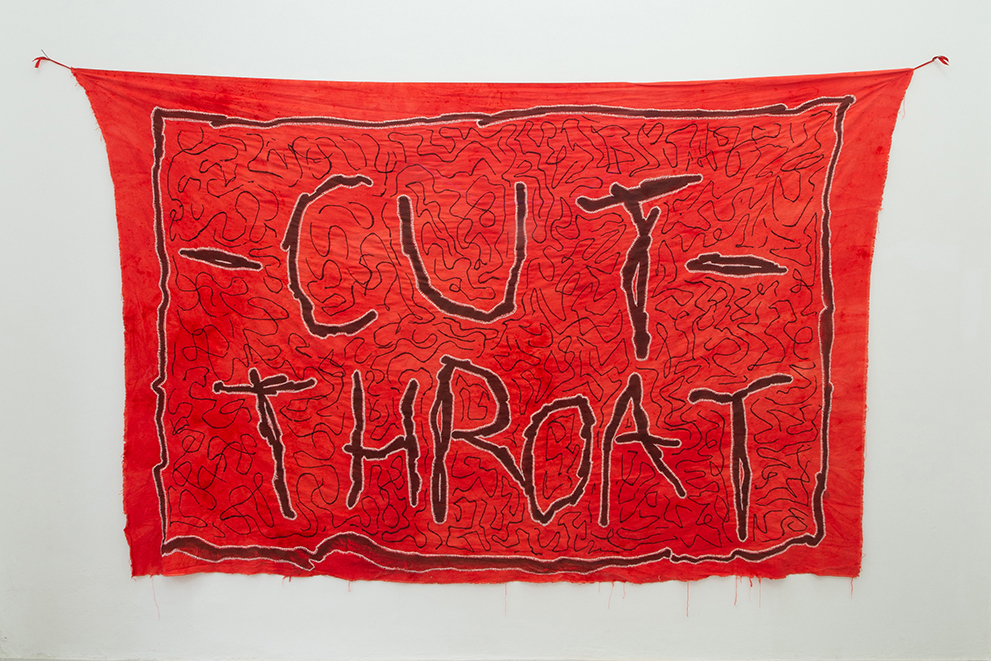

The search for this ideal hole that overcomes the difference that I have just mentioned, along with the pursuit of related simultaneities, seems to be the main concern in Nicolás Astorga’s current show. If Everything hurts, it also hurts what causes pleasure, which seems to be sufficiently clear in the artist’s statement — everything hurts, even though the author of the text confesses to avenging an old betrayal. Hurting hurts too, just like a Sharp tongue (words like blades) ends up completely bloodied and chopped up — someone outspoken ends up without their tongue (the speech is taken out).

A tongue-less mouth, a mouth that cannot speak, perhaps it is the first step to reach this ideal and complete hole, My hole, the show’s origin point and also the black hole towards every other work is being dragged as they explore and insist, through different means, on the issue of mutilation, but subtly and far from gore: seems that the blood is already cleared up, as in Vermin (Alimaña) and The Nine of Swords (Self-Portrait), or is dried up like blood in a towel, as in the dark red colored prints Fire mark and I wish you would…

The subject of mutilation is worked through, beyond its resonances of spectacle and sacrificial feast, to become a matter of contemplation and meditation, as in certain representations of martyrdom found in Christian medieval and colonial art, and in some tragedies as well — for instance, Seneca’s Medea, a play only written to be read and not to be performed. Now turn to this other “center” of the show, The Nine of Swords (Self-Portrait), the taxidermy of a horse, an animal, according to Bataille, that can be “rightly considered to be among the most perfect and academic of forms (…) the horse, situated by a curious coincidence at the origins of Athens, is one of the most accomplished expressions of the idea, just as much, for example, as Platonic philosophy or the architecture of the Acropolis”.

However, the horse of this self portrait is not a full, rounded idea: it’s just half a horse, perhaps a half-finished idea, submerged, peeking to the surface — or perhaps sinking beneath it. Not showing himself his full body, the horse’s predicament could be linked to a sense of shame — the drive to not show, not expose yourself —, as is suggested towards the end of the artist’s statement: “My head is so big that I always thought I looked like a horse”. This idea of shame as a desire to not show yourself I think is explicitly referenced in the work’s title, a Tarot card whose image evokes the interruption of sleep by the re-emergence of that which should not be exposed (i.e., the repressed). The swords piercing the body of the horse refers to the classic icon of Saint Sebastian and his body wounded by arrows — an image that has been interpreted as an allegory of pain caused by the repression of desire, a situation comparable to martyrdom.

Understood as the inwards drive, towards your own, inner hole, the sense of shame is thus a withdrawal to the intimate, a necessary moment in the construction of the subjectivity that allows the work of art to happen — a hole that expels and swallows.

But I will stop interpreting now. After all, it is not my idea to keep doing the name dropping, and the artist himself — when he invited me to write about these works while we were on our way to a party called Sein (“Being”) — demanded that this text should be an emotional outpouring, that I would hopefully ventilate details of his life, to which I could also add rumors, and that I could even talk trash about him if necessary.

Against his wishes, I remain silent, and look into the hole.

Domingo Martínez