Archive

2020

KubaParis

itoo-close-to-far

Location

Studio PRÁMDate

08.06 –29.06.2020Curator

Šárka KoudelováPhotography

Šárka Koudelová, Anna PleslováSubheadline

Ondřej Basjuk, Barbora Dayef, Martin Herold, Šárka Koudelová, Jiří Kovanda, Matouš Lipus, Raja Meziane, Tania Nikulina, Pavel NovotnýText

The project Too Close To Far, and its accompanying short publication, likely would have had a different accompanying text. Yet even though this previous text would have probably worked well enough for the exhibition before the pandemic, it now, in this post-pandemic context, seems insufficient or maybe even a little naive. We still do not know what the virus will bring, what changes it will force or how many people in how many waves will die from it, but we can already be sure that the pandemic has highlighted both the positives and negatives in the global community in general as well as in the community in your street. The pandemic has seeped with a cathartic force into the planning and realization of the Too Close to Far project which, similarly to other events that are contrasted with the global crisis, seems totally pointless now. But the project seems tailored for the current situation even more than in any pre-pandemic state of its preparations. The name of the exhibition foreshadows the polemics about the physical settings of an event, our relationship with this place and subsequently, with its geographical name. Over the past five years, the crisis has in various forms affected almost all areas of life on Earth. Hybrid conflicts, wars and consequent migrations, fear of immigrants, humanitarian disasters, rising populism and nationalistic tendencies across all political spectrums, and the climate crisis that has brought about a global anxiety and almost no effective changes in the system. Moreover, this year has brought about a total paralysis caused by the pandemic, and the thoughts about the future have been hit by a completely new type of anxiety.

Despite the constantly contradicting information streams, fake statistics and conspiracies, the current state let us feel an uncertain hope about saving the world. The current crisis has had a positive effect, just like any previous crises. It has brought forward our dependence on nature, on the place where we live and mainly our interconnectedness with people all over the world. Refugees from the Middle East, whose homeland we consider a faraway exotic land, can walk to Europe by feet. The spread of the virus has further highlighted how artificial and permeable state borders are and their hardly definable capability to protect citizens. Even though we have been living in an open world for a decades, we might only now be realizing the ongoing history as a sequence of events spreading like ripples on the water’s surface.

Currently, the geopolitical units that divide the world into a class system based on lower, middle, and upper class are more important than the borders between individual countries. Although some might assume that the term „decolonization“ might have gotten under our skins since the 19th century, and therefore that its theoretical process might have become reality. Even today, this overused term still remains a half empty slogan. Global powers have technically left their colonies. They recognized their independence and recently even some west-European institutions have started returning exhibits from formerly colonized territories. But decolonization does not only mean returning stolen artifacts from world museums to their original owners. It is a way of thinking, or more precisely, the need to change it. The Euro-American society still does not fully realize how their thinking, interpretation of history and attitude towards other systems are all rooted in imperialism from the previous centuries. Even when reading a map, we navigate as European colonizers – terms such as Middle East or Far East only make sense from the European perspective. This arrogance is not limited just to geographical labeling; it also includes the perception of cultural history. How difficult it is to step out of the conviction that we are, as mankind today, the smartest we have ever been? How are we still able to call some cultures or historical artifacts primitive? Why the merging of the East and the West, as political end economical division from the past, has egoistically sufficed our hopes for freedom in central Europe, but the still existent border between the North and the South, or better to say their inequality, do we considered a given?

If we see decolonization as material as well as intellectual exhaustion of the weak by the strong, we should then decolonize the perception of politically unstable countries, different cultures, and the passage of time and nature. We need to decolonize our thinking from the idea that anything in the world is here for us to use.

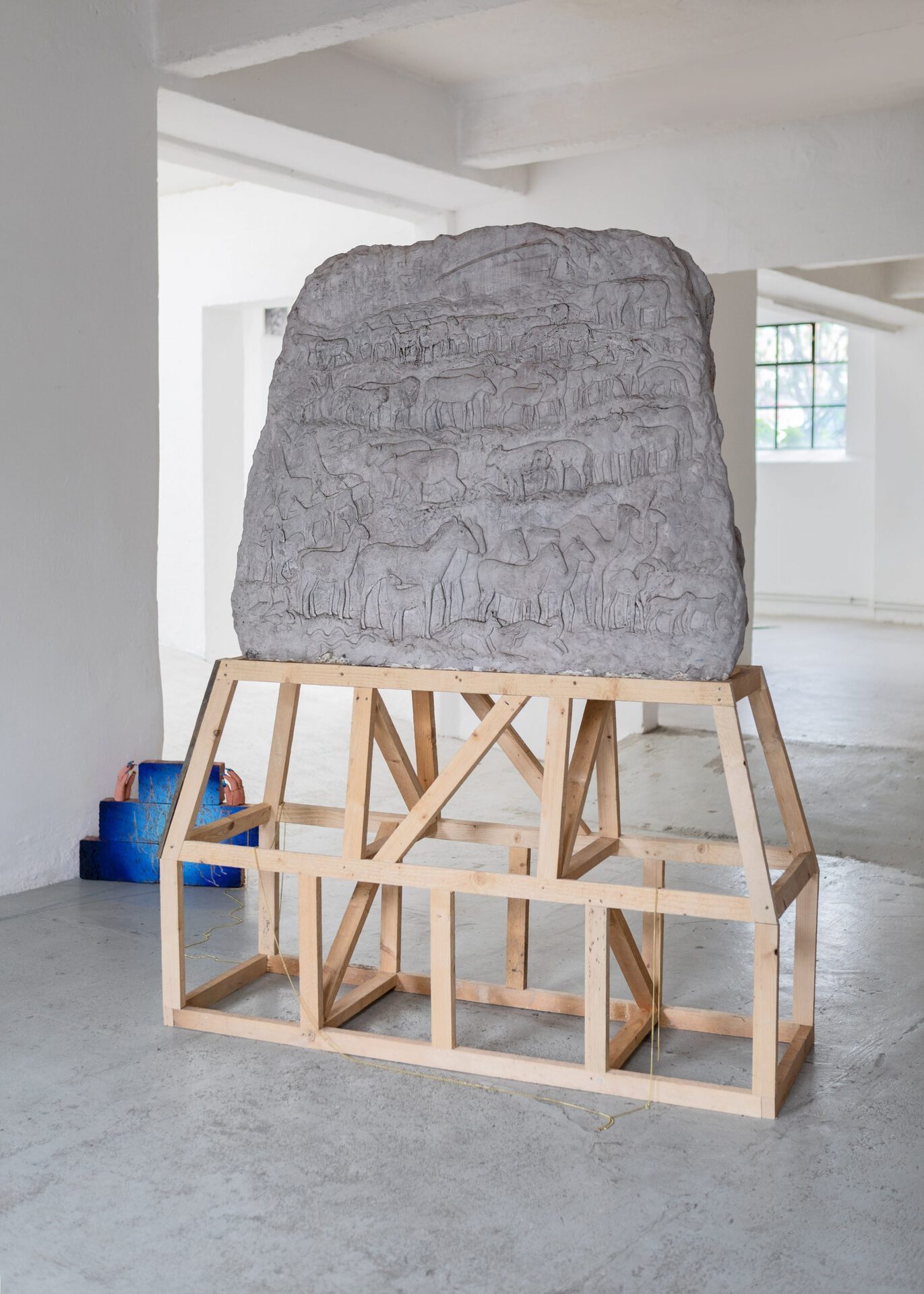

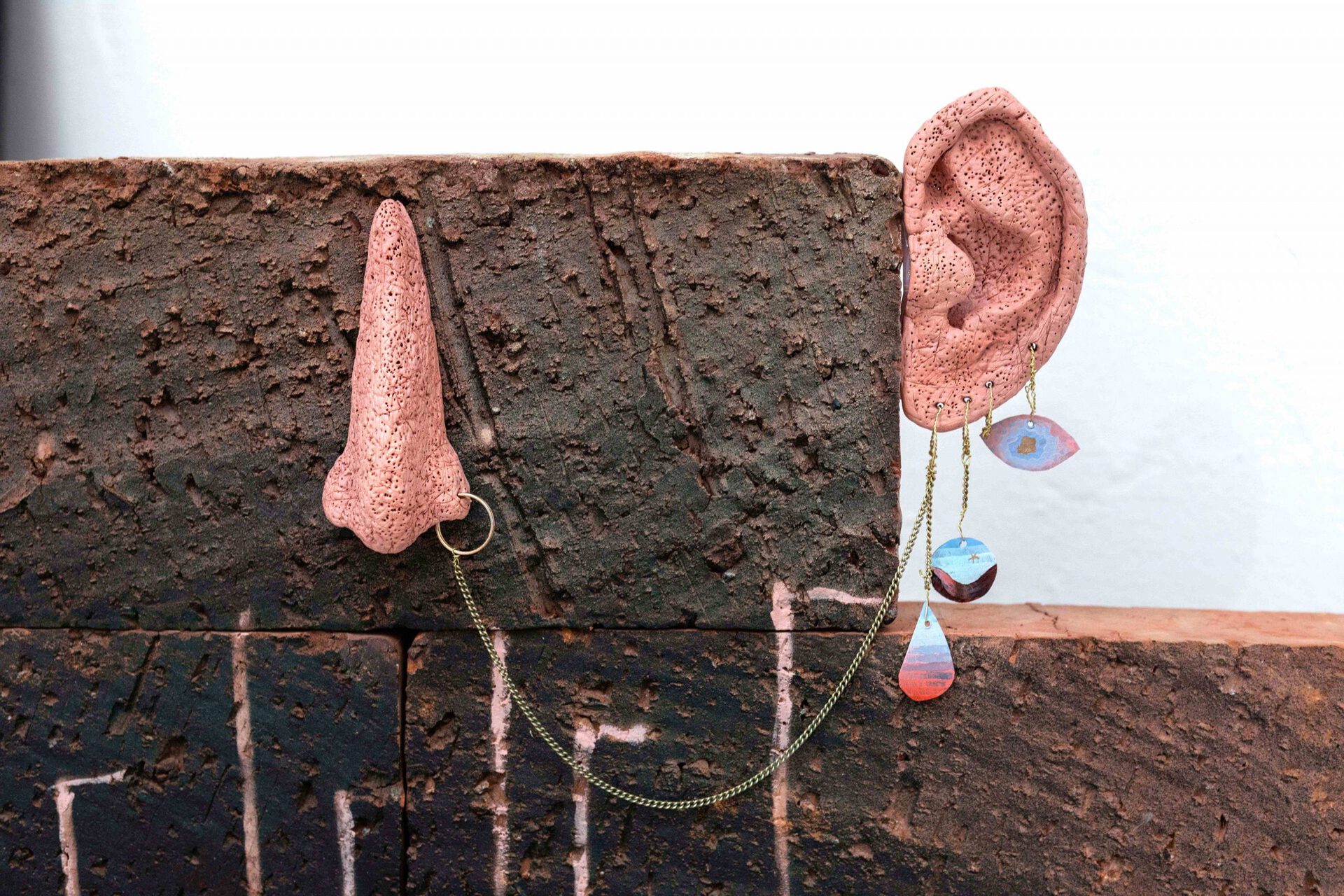

The perception of the synchronicity of time has already been disrupted by radio and TV broadcasting, so how is it possible that in the time of YouTube, podcasts and Instagram stories, when any audiovisual content can be viewed at any time, we still insist on a linear perception of history? The collection of works from the invited authors presents the idea that who we are is more important than when and where we are. It is not important when and where we create a piece of art, compose a protest song, or start a revolution, because as soon as it is published into the global virtual space, it becomes ubiquitous and since it can be viewed at any time, it cannot be firmly fixed on a historical time line. Too Close To Far is deliberately attended by artists who live in Prague but who have different cultural backgrounds that they reflect in their work. Other participants update historical cultural artifacts in contemporary languages or symptomatically work with space division and basic emotions. Brick objects – labels that interconnect the whole exhibition and bring forward the importance of “words” ,in the sense of naming, and also highlight the moments when a title turns into a generalizing or superordinate label. The material of the bricks refers to the construction of the Tower of Babylon – the symbol of language confusion, human pride and the desire for senseless constant growth or even the biblical creation of man. The pseudo decorative calligraphies that follow the ancient brick glazing are symptomatically stylized by Earth’s gravity.

Pre-pandemic global connection was at the point where the spread of the disease between continents was as easy as between adjacent cells. Spreading just as quickly are images, sounds and information. Pavel Novotný, the author of this catalog's introductory text, is a seasoned carrier of these elements of our perception. As a journalist and reporter from unstable areas or war zones, he takes on the task of drawing facts, images and emotions which he then interprets for Czech media.

Modern technologies allow us to share a live coverage or even an ordinary video call in real time while also having the option of playing them at any later time. If we accept the idea that technological evolution has eventually over the centuries, without us noticing, caught up to the age-old desire of humans to send their thoughts, even a simple sending of email can be seen as a mystical ritual. In the last couple of months, most of us have been living without physical contact with other people. Instead, we have focused our strangely slowly passing days to online communication. So we meet in the virtual world, a space that is not on any map. This place in which we meet and to which our minds temporarily move moves from one corner of the world to another, is still an unnamed mystical destination – a virtual continent, the last version of Babylon.

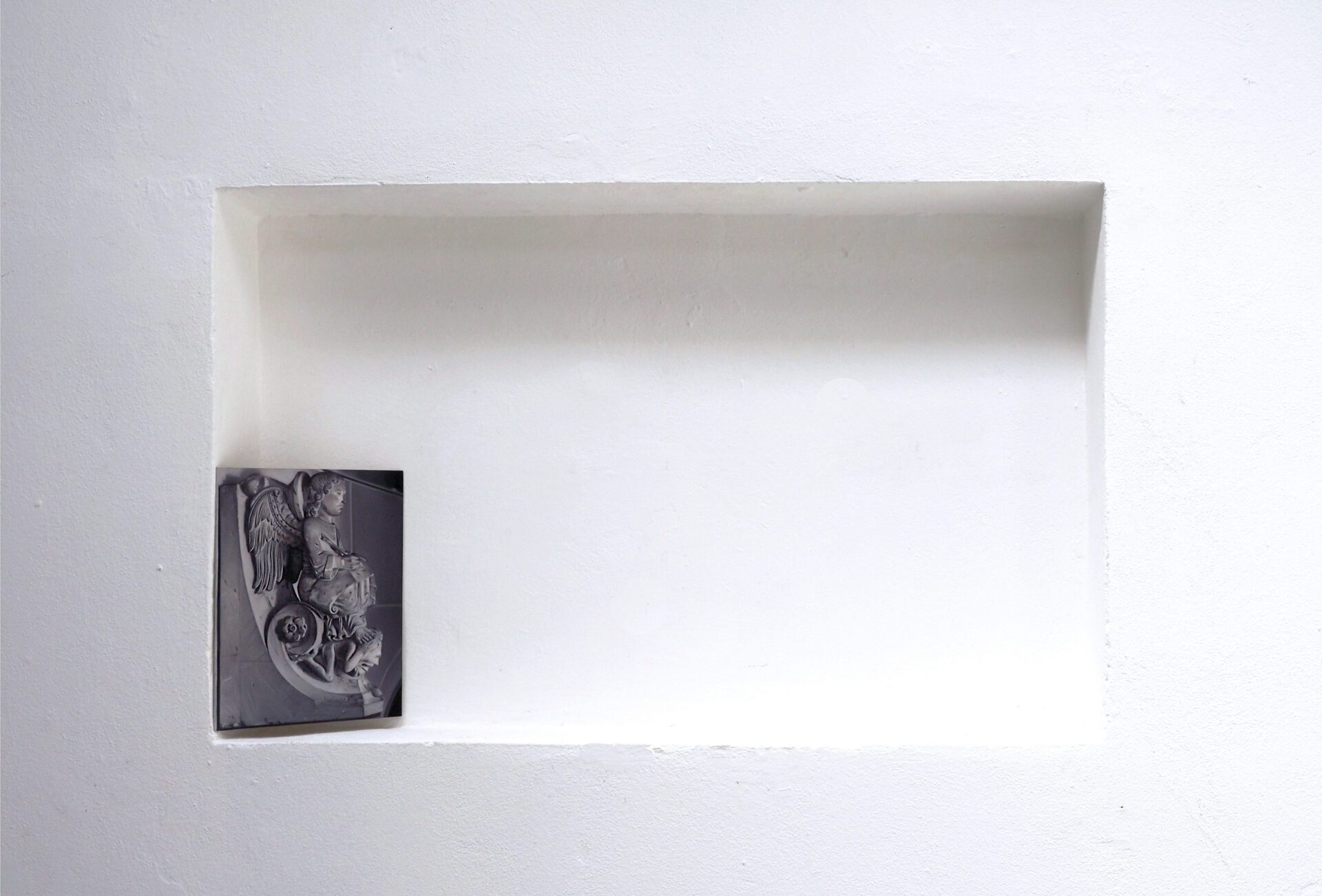

The exhibition and its accompanying publication is not an usual curatorial selection of works by a group of artists. Ideally, it is a project that exceeds its current location in space and time. It might also be a potential answer to the hypothetical question, what would a collection labeled “Prague” look like in 2020 if a hypothetical colonizer would want to collect representative samples of artifacts? The collection in Ondřej Basjuk’s installation presents the possibility to observe recent local history while Matouš Lipus’s sculptures look at the archetypal Old Testament-like and distant history. It offers Martin Herold’s unique perspective on Romesque iconography, and on the perfect illusion of paintings and in the objects by Barbora Dayef it confronts the viewers with their perception of the unknown. Any debate about the current meta crisis and regrets about the past often seems as a history of ever resolving conflicts. Jiří Kovanda show the opposite through his iconic performance, a positive motif of overcoming obstacles, so the fragile remnants of a temporally limited event remains in the exhibition as a silent reminder of nonviolence. The subconscious theme behind Tania Nikulina’s installation is healing – the fact that our society is sick and that it can probably be healed by natural and occult resources was in the public discourse long before the pandemic. The exhibition has its own soundtrack – a selection of tracks by Raja Meziane, whose music videos are an integral part of the whole project. Raja came to Prague in 2015 and only because of her emigration she was able to become the uncensored voice of the Algerian anti-regime protests. The song Allo le Système! has therefore become the anthem of activists in the streets of Algeria, even though Raja published it on YouTube in Prague.

When the general public and its official representatives accept a decolonized way of thinking, it will be necessary to name a new concept and find a new map, because the current one has been considered valid for way too long. We have been paying attention in the last couple of months to China and the Middle East, because where else in the world can we predict the future than in these quickly changing places and development of mythical IT technology? If we do not destroy conditions for human life on Earth first, if we let go of conspiracy theories and orientalist clichés without forgetting about the archetypal mythologies older than our collective memory, we can look forward to ethno-futuristic tomorrow.

Šárka Koudelová