Archive

2020

KubaParis

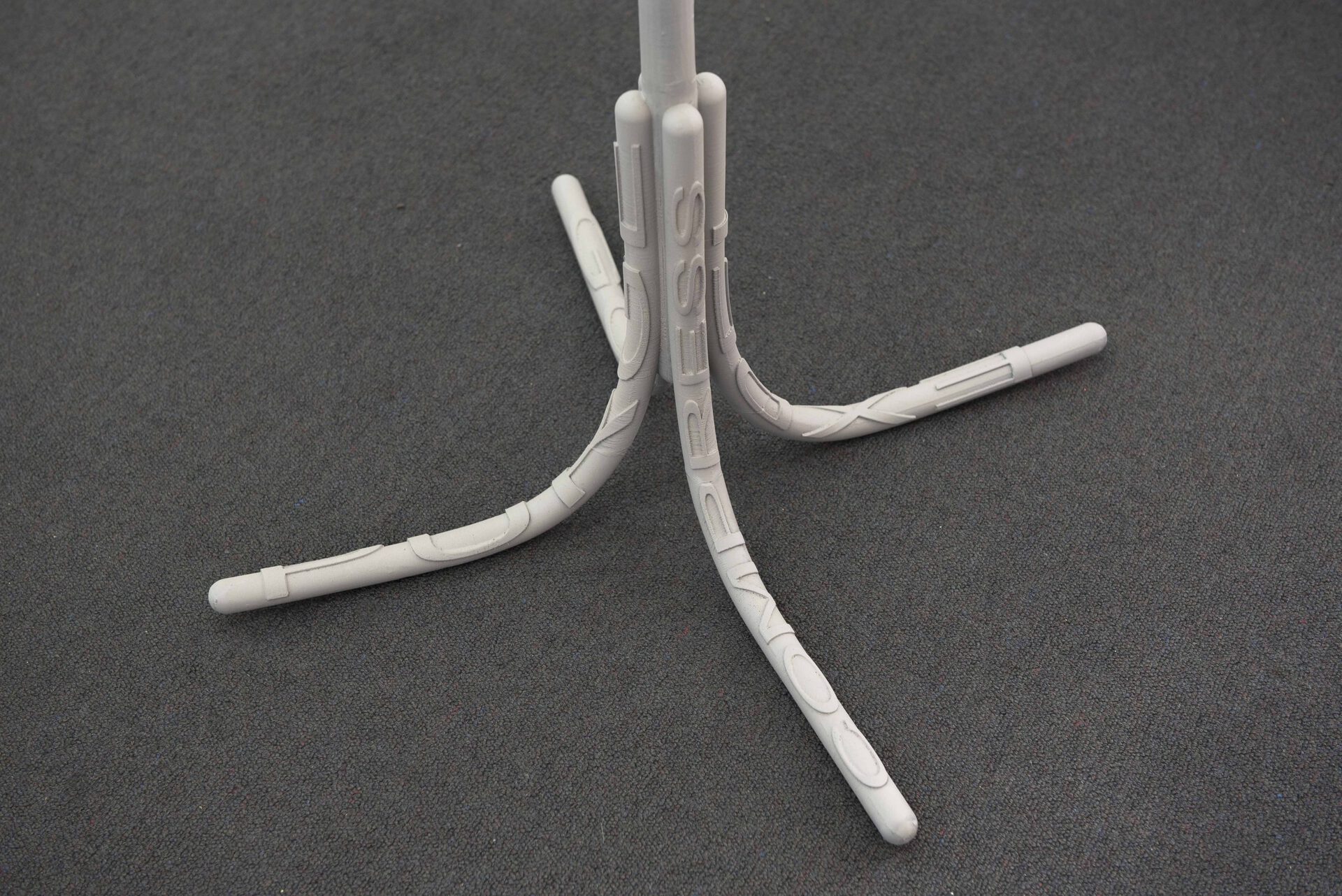

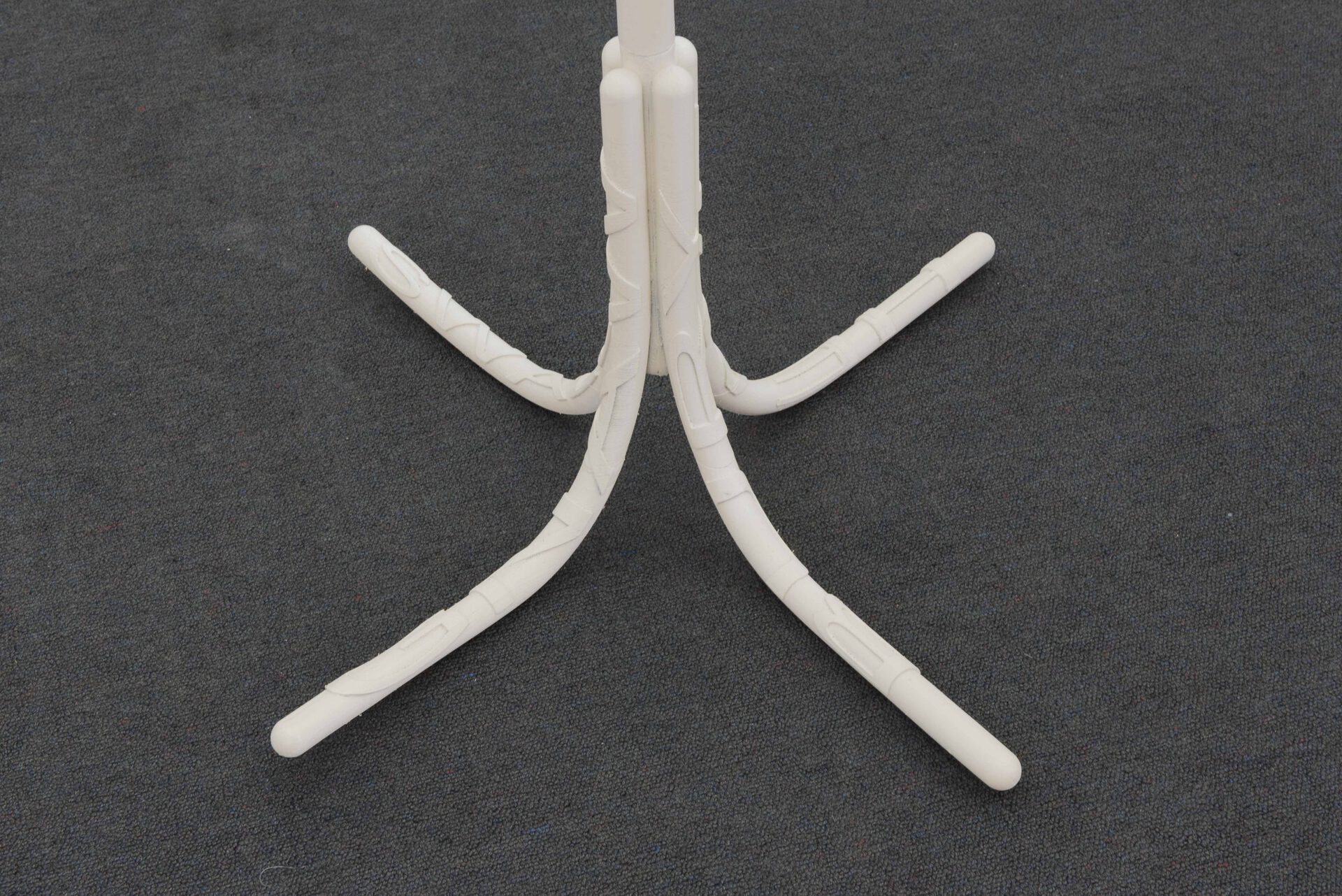

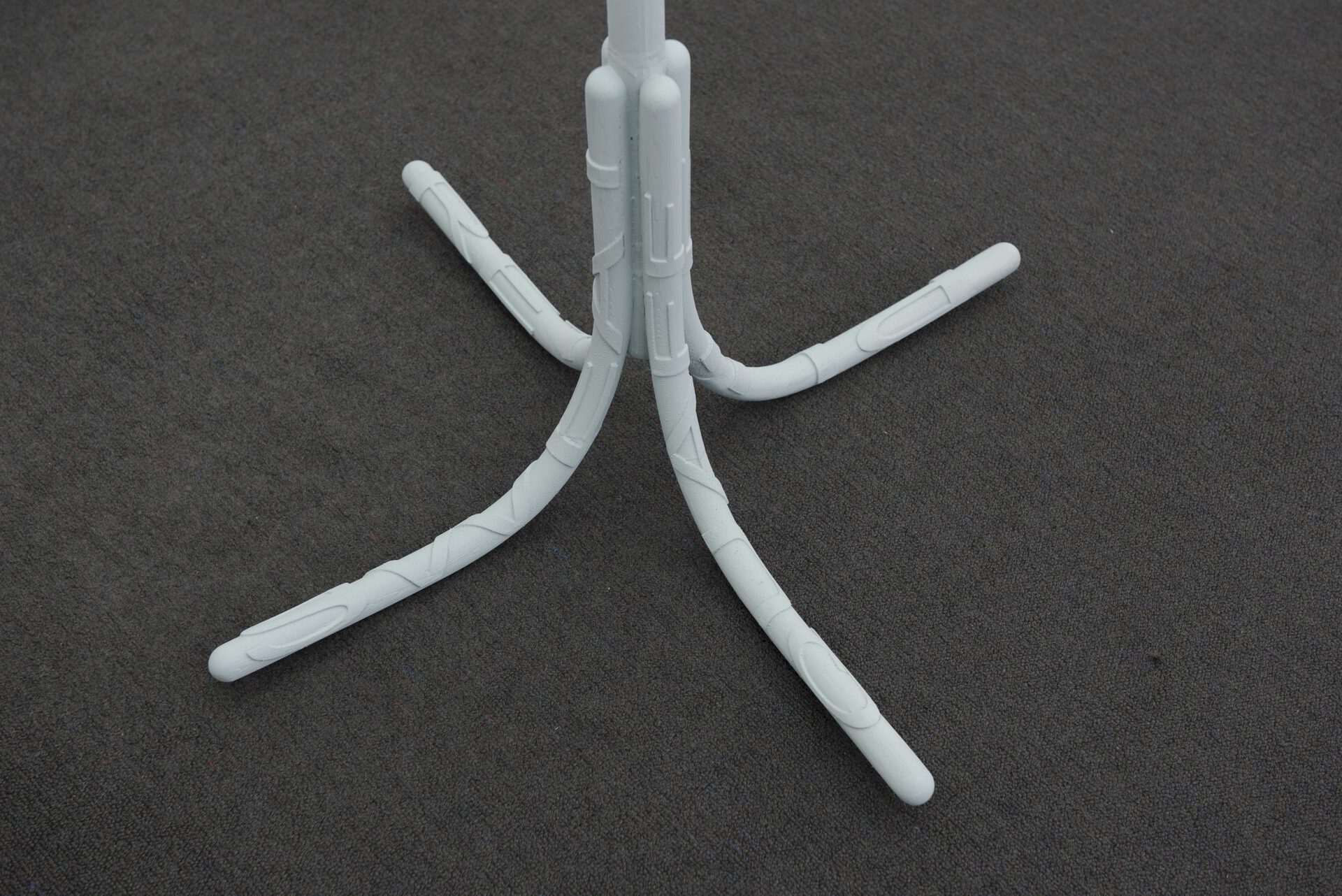

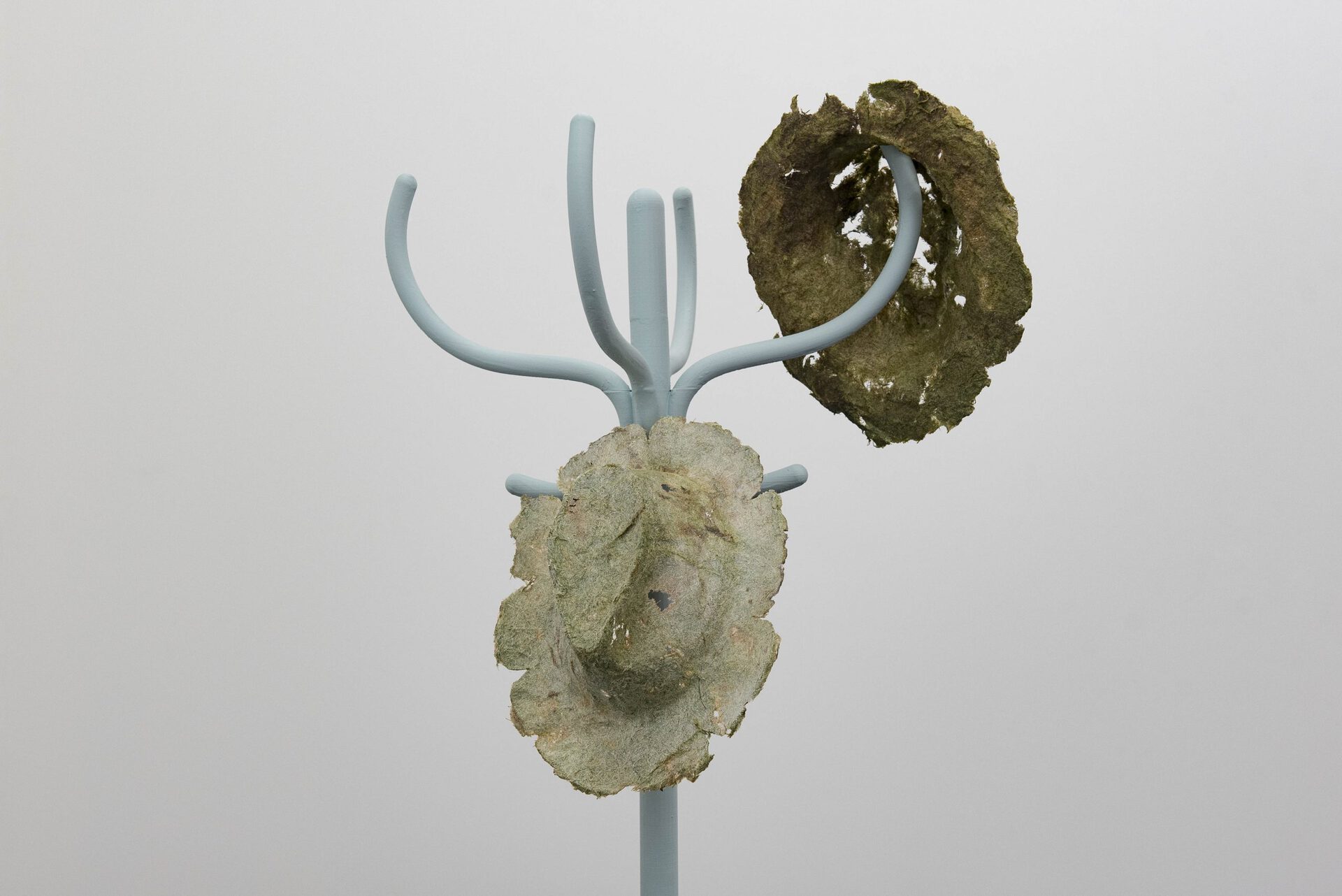

Fertilizer

Location

Conners ConnersDate

18.12 –21.12.2020Photography

Jordan HalsallSubheadline

Conners Conners is excited to present new work by Melbourne-based artist Jordan Halsall. His interest in art lies within its capacity to embody and represent dissonant ideologies. Examining the human body as a node that functions through its surrounding media based technological infrastructure, the work journeys through growth, surveillance and optimisation.Text

“You cannot dig a hole in a different place by digging the same hole deeper.” – Edward de Bono, 19931

Following his conceptualisation of lateral thinking, the psychologist-turned-corporate- consultant Dr. Edward de Bono developed a method for creative thinking conveyed through what he termed thinking hats. The six thinking hats - outlined in a 1985 self-help book of the same name – separate our thought processes into defined, colour-coded modes: If one cannot solve a problem creatively, they can simply switch hats, approaching the same problem emotionally or cautiously or positively and so on...

de Bono’s thinking hats operate on the premise that one cannot be objective, logical, emotional and creative at once if we are to think and behave effectively. When projected onto the complex cognitive abilities of the human brain, these ‘distinct’ modes of thinking appear increasingly facile - but when adapted to an increasingly virtual world, the hats themselves begin to stress and decay. The infinite scroll, context collapse, cultural flattening. These facets of the internet invariably obscure our ability to wear these hats separately, as we absorb posts about current atrocities and trolling shitposts in the same breath.

If de Bono is correct about one thing, it is that we have to dig holes in different places: build new platforms, access new ways of thinking, and not let the content we consume direct our ideologies down a linear path. It is easy to subscribe to a way of thinking that mirrors what you have seen online, the poster becomes the ideologue and the platform becomes the politic. This is often referred to broadly as the ‘filter bubble’. In the words of internet activist Eli Pariser, “your filter bubble is your own personal, unique universe of information that you live in online. And what’s in your filter bubble depends on who you are, and it depends on what you do.” Forbes Magazine questioned whether 2017 was ‘The Year of the Filter Bubble’, while Mark Zuckerberg’s ‘Building Global Communities’ manifesto insisted that filter bubbles are not an algorithmic issue but exist due to media sensationalism and polarisation. While well-intentioned, the concept of a filter bubble parallels the great triumph of the nomenclature of The Cloud; the fluffiness of which manages to obscure the physicality of the Internet of things: server cooling, data centre geopolitics, hydroelectric and geothermal power, aluminium, copper, steel, e-waste. Similarly, the imagery of the bubble has been co- opted to put the onus on the individual, sidestepping the fact that these bubbles are manufactured for peak engagement. The implication is that we are to reach out and prod until they burst, manually diversify our own social networks and media consumption - or simply tune out.

A better framework emerges through the concept of a Walled Garden. Used as a marketing term, the Walled Garden is a closed ecosystem: platforms that keep their information, tech, and most importantly user data to themselves. Walled Garden platforms, like Amazon, Google and Facebook, gather large swathes of information about their consumers, offering this data only to those who operate within their own walls. As we think about our bubble: intellectual isolation, echo chambers (the same ideas, memes, and pastel infographics being shared) – it becomes clearer that this is not an organic ecosystem. We are enclosed in a series of walled gardens, mazes that are viewable from above but complex to navigate once placed within them. Returning to de Bono, the thinking hats decompose within these walls, muddled and overloaded or streamlined and uncritical. It is appearing ever more likely that these bubbles cannot be burst and walls unable to be climbed, but there is still room for tending to the soil.

Howard Palmer