Archive

2022

KubaParis

Miraggio Inferiore

Location

ArtNoble galleryDate

02.03 –28.04.2022Curator

Piergiorgio CaseriniPhotography

Michela PedrantiSubheadline

The first solo exhibition of Roberto Alfano at ArtNoble gallery, Milan, curated by Piergiorgio Caserini.Text

ArtNoble gallery is pleased to present Miraggio Inferiore (Inferior Mirage), the first solo exhibition of artist Roberto Alfano at the gallery, curated by Piergiorgio Caserini.

An inferior mirage is the asphalt bobbing like the sea. It is an effect of the heat, the humidity and the distance, a strange inflection of the above on the below that everyone knows well, but especially those who have always been accustomed to infinitely long landscapes and horizons where the gaze is so wide that it is only possible to follow things as they disappear. Obviously, we are talking about the plains: the Po Valley and the Emilian plains. Expanses dotted with farmhouses, courtyards, bell towers, aqueducts and pylons, framed by the geometric shapes of muddy ditches, embankments and drainage ditches in which families of nutrias wallow, surrounded by small swarms of fireflies; in short, those landscapes in which steaming piles of shit, gravelly mud on the embankments, occasional floods and, recently, tornadoes, recur. Let us say with the certainty of those who live them that these are such vast spaces that it is easy to get lost whilst standing still. They are landscapes that have the peculiarity of urging the observer to continually exercise a glance into the distance, at what disappears and what only appears when walking - and here we live on opposites: the fog is the ultimate fallback, where things rather than disappearing suddenly appear. In short, the long, seemingly infinite spaces facilitate the mirage, whether it is inferior or superior: whether it is the sky that makes the asphalt and the earth vibrate, or the mountains that disappear below the horizon.

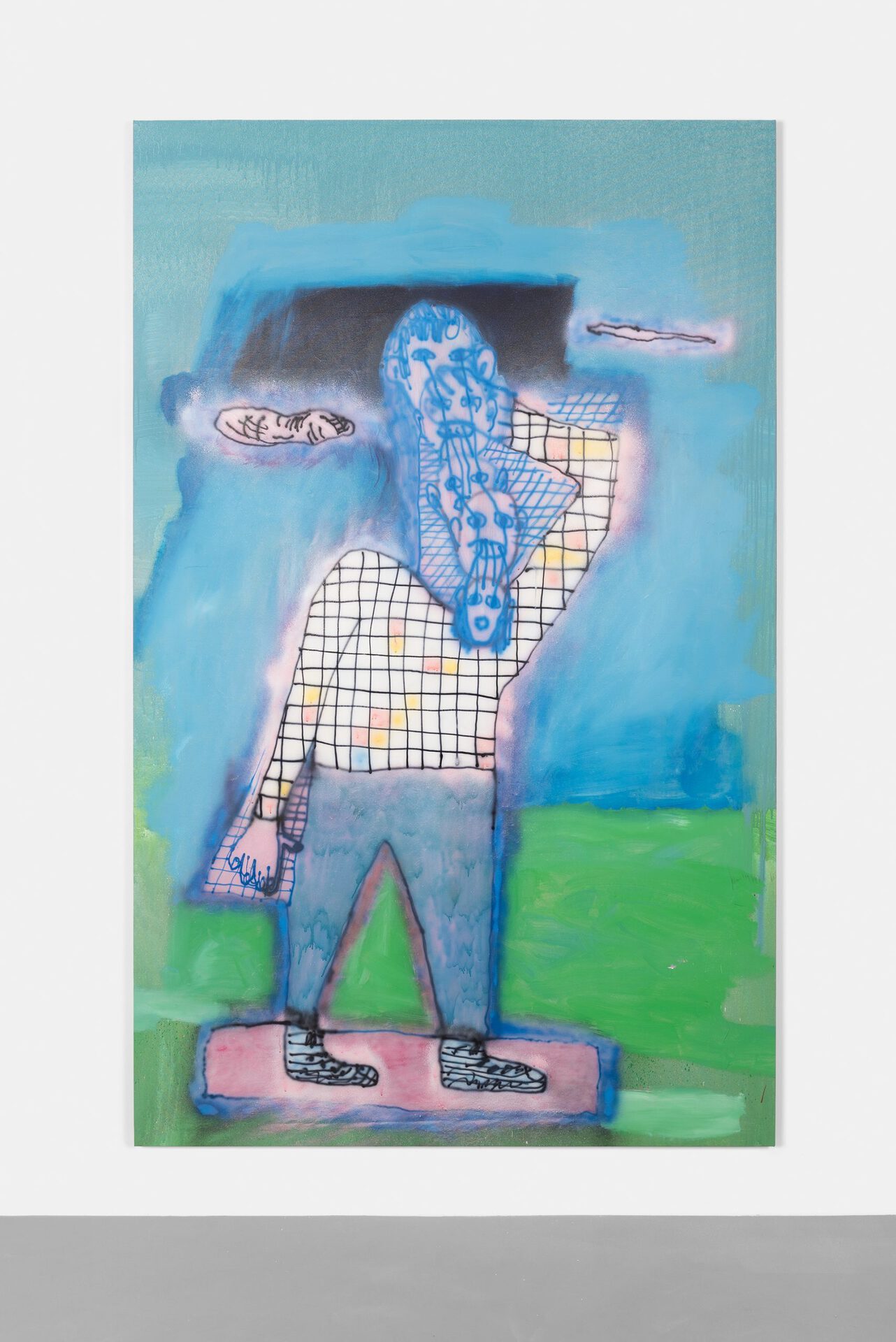

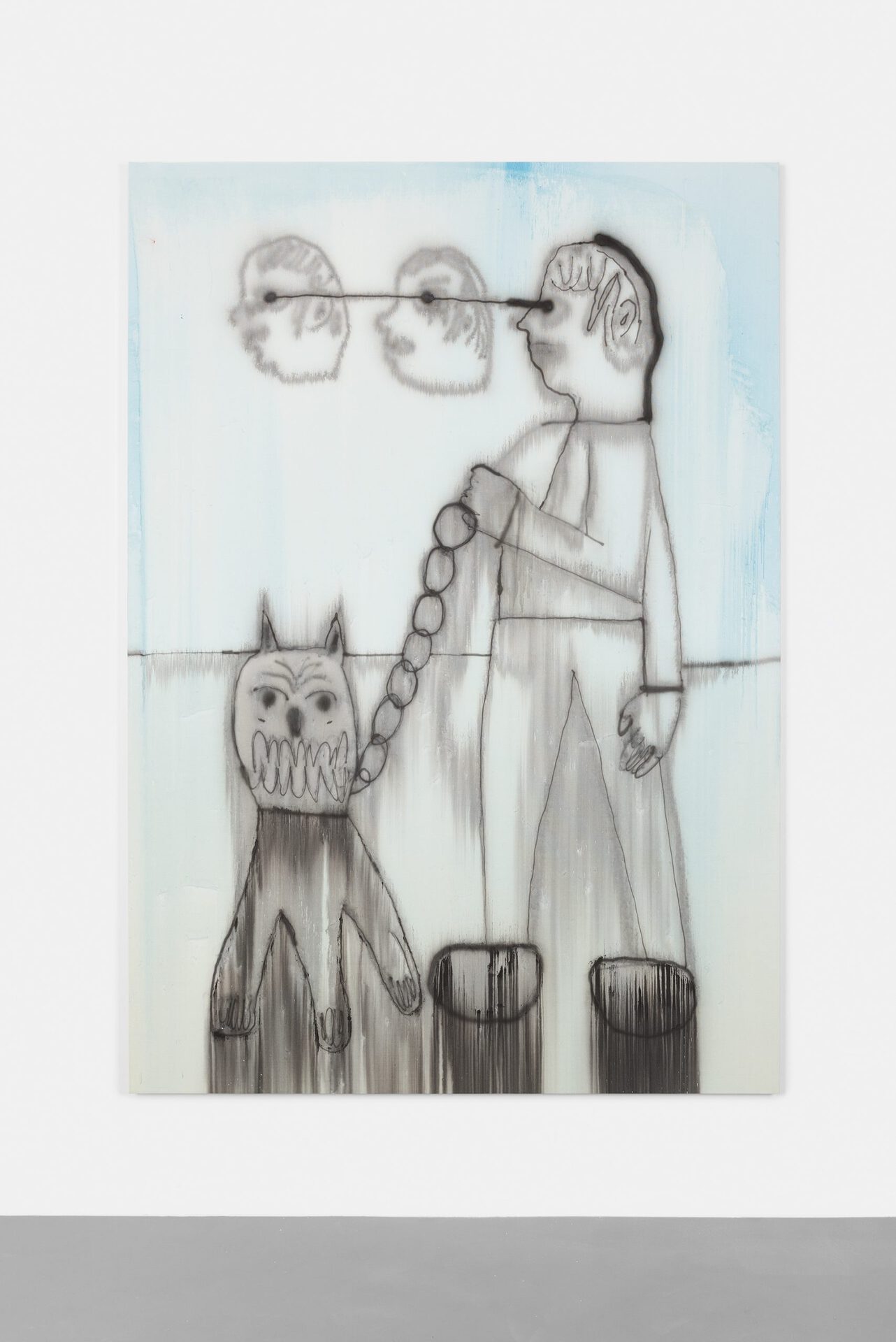

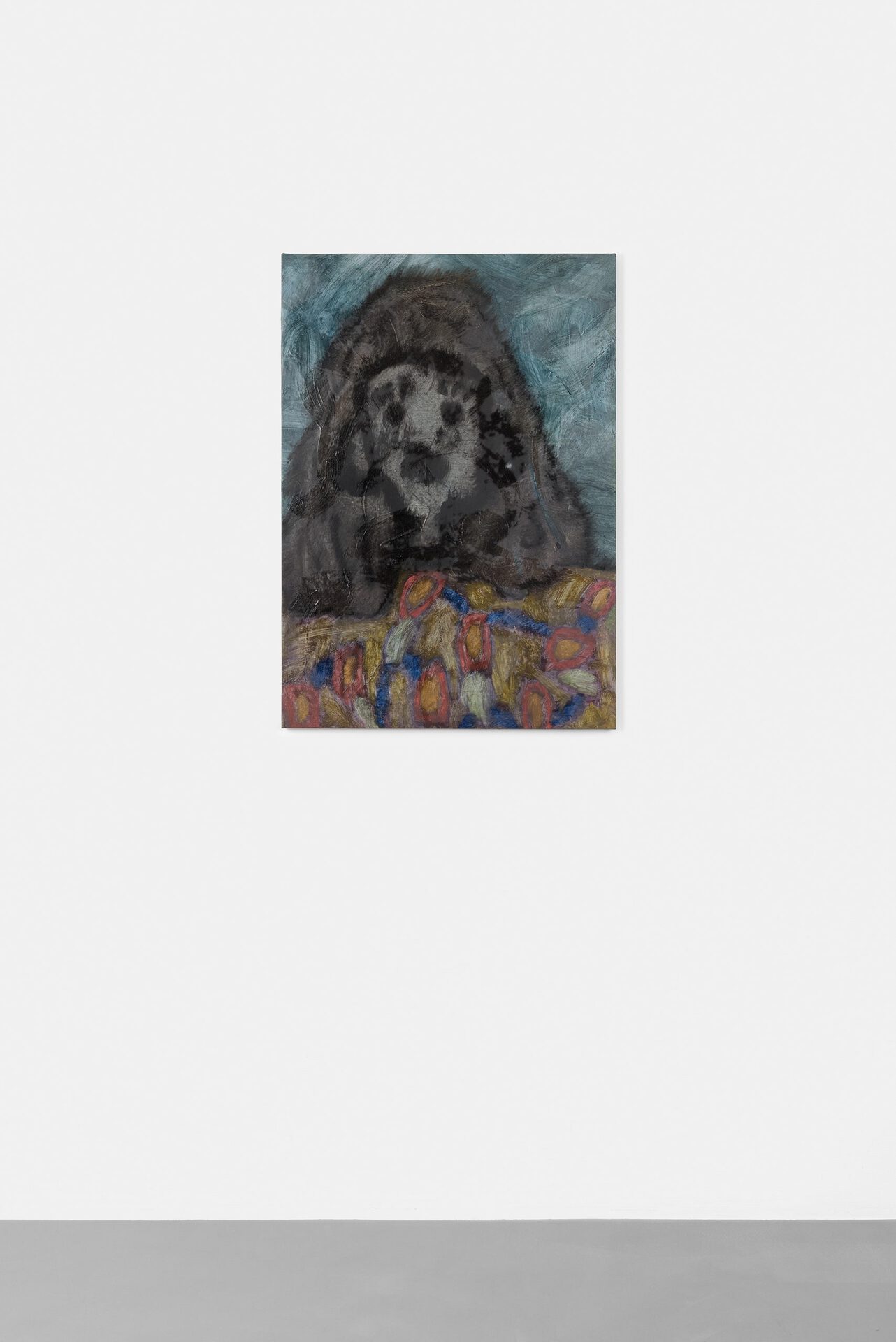

Let’s start from a postcard that draws on decidedly biographical aspects. Roberto Alfano, for those who don’t know him, grew up between the industrialised moors of the sub-rural area par excellence, the Lower Lodigiana, and the livelier and more flooded expanse of the Emilian plain. The postcard in question is an image or a memory that seems at first glance to rummage around with that neo-realist bucolic of the farmyard courtyard, children running in the fields, dogs and walks. And it will immediately seem as if the subjects of Miraggio Inferiore are dogs: dogs of wood, dogs of earth and clay and cement, dogs of cloth and sequins, spotted and striped, motionless and snappy. You will see that there is a shack, just like the abusive ones so often found at the base of motorway overpasses, where you never know whether the mist is actually pollution or vice versa. You will also notice the recurrence of figures and signs with childish features, and this is where we commence.

Roberto’s entire production is characterised by at least two distinctive movements. On one hand, there are figures of fantasy: a childlike attitude of disorientation, of stubbornly following a kind of childlike trait that chases after forms, portraits and scenes. On the other, the obsession with the repetition of elements. If we ask ourselves what a childlike trait is, we must think of a game of forced - but still likeable - sympathies. Which means not allowing things to happen, but rather imposing the reality of fantasy, and opening up adventures where it seems there are none - and here, if you want to imagine it, the figure of the horizon can return again. But the fact is that these dogs mostly have one thing in common. They are disproportionate, some too small and others almost deformed, some grotesque and others tender.

It could be said that some of these are affected by neoteny, which is that evolutionary oddity, the culprit of which falls mostly on the co-evolutionary processes of domestication and selection, whereby friendly canids have not only, for example, long, tender ears and large, soft skulls, but also behavioural characteristics more akin to a puppy. And the perceptual result is that of an aura of tenderness, of cuddles and caresses, almost as if one could think that those affected by neoteny receive a strange reality by reflex. A lysergic reality, as if one were always and only looked at and squared by the eyes of childhood, which are eyes that see things from a different perspective together with what they actually are. It means they are dogs, but almost. Almost-dogs. Exactly like the most grotesque and spectral figures, the masks exacerbate a wild violence as well as exhibit the fascination with ideas of freedom.

In Miraggio Inferiore and in the rendering of dogs, a motif of identity is revealed. Of wondering where the limit is between what one sees and what one thinks, and inscribing the problem in a postcard-image, that is to say in a landscape that bends the gaze in a certain way and modulates the sensations accordingly, just like a childlike trait, or a mirage: which throws out figures as they are, turns a dog into a patch, a piece of wood into a body, a lump of clay into a monster, so that a house is also a shack and the onlooker pours out continuously at the foot of the horizon in which he is lost, just to wobble for a few minutes along with the asphalt.

In short, to close this long text, which is more of a dialogue than anything else, let us say that looking at Roberto’s work we find ourselves faced with one of the most difficult aspects of that thing called “art”, which has as many forms and figures as it is put into practice, and which is perhaps, at heart, an aspect of expression: its necessity. That of being able to constantly cope with the things that appear and vanish, that afflict the soul and break it up in every portion of the gaze, in every visible one, those affections that - if intense - make it difficult to distinguish between who is looking and what is seen, between looking and being looked at, between the paranoia of a shack in a space so large as to seem infinite and the strange freedom of disappearing into the same space.

Piergiorgio Caserini