Archive

null

KubaParis

my-very-favourite-very-beloved-things-3-cruising-the-exhibition-by-alke-heykes

Subheadline

Within the small series "My very favourite, very beloved things", thoughts and texts are published that didn't make it off the desk last year - but which tell us of exhibitions, works and things that still haunt the authors sand demand a turn towards the outside.Text

The few indirect red lights, the Disco and Deep House music and the bar setting immediately relocate the visitor at the beginning of the exhibition into gay bars like Möbel Olfe in Berlin or Sidetrack in Stockholm. Baren is the name of this first of three rooms in the exhibition "Cruising Pavilion: Architecture, Gay Sex and Cruising Culture" at ArkDes, the national museum of architecture and design in Stockholm. This exhibition marks the end of the trilogy of the curatorial project "Cruising Pavilion" around the architects and curators Pierre-Alexandre Mateos, Rasmus Myrup, Octave Perrault and Charles Teyssou. Following their debut as an unofficial part of the Architecture Biennial 2018 in Venice and the "Cruising Pavilion New York" in Ludlow38 in spring 2019, the curatorial collective presented their last edition for the first time in an institutional setting.

The music in Baren is a mix of Dirty Disco, Deep House and tracks from porn, all of which are strongly linked to the LGTBQ+ past and present, from the "Cruising Pavilion Fire Island Mix" (2019) by Steven Warwick. The curators show the other artistic works beside Baren / The Bar in the successive rooms Darkroom and Sovrummet / The Bedroom. This scenography was set up in Boxen, the ArkDes' exhibition space designed as a room within a room. These three rooms are traditional spaces in which gay cruising takes place. Cruising is the quest for sex between homosexual men in public and semi-public places. This can take place at lakes, in parks, parking lots and public toilets, but also in designated places such as gay bars and saunas, bathhouses and sex clubs. However, "Cruising Pavilion" shows that cruising cannot be fixed to a specific place and by no means takes place only between men. Further, Cruising Pavilion explores ways in which cruising has challenged and continues to challenge normative architecture, urban planning, established modes of display and concepts of the public sphere.

Exhibiting Subversion

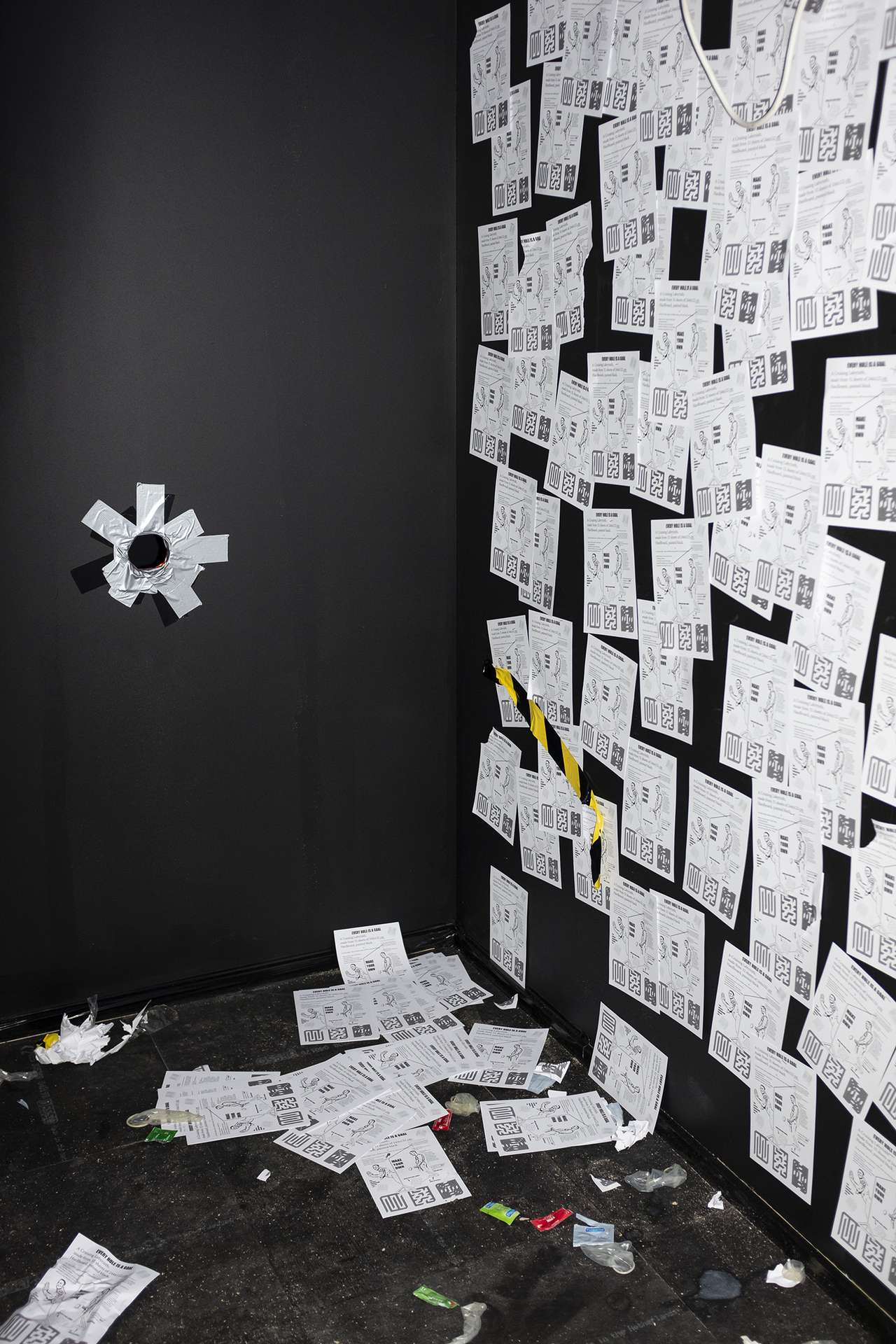

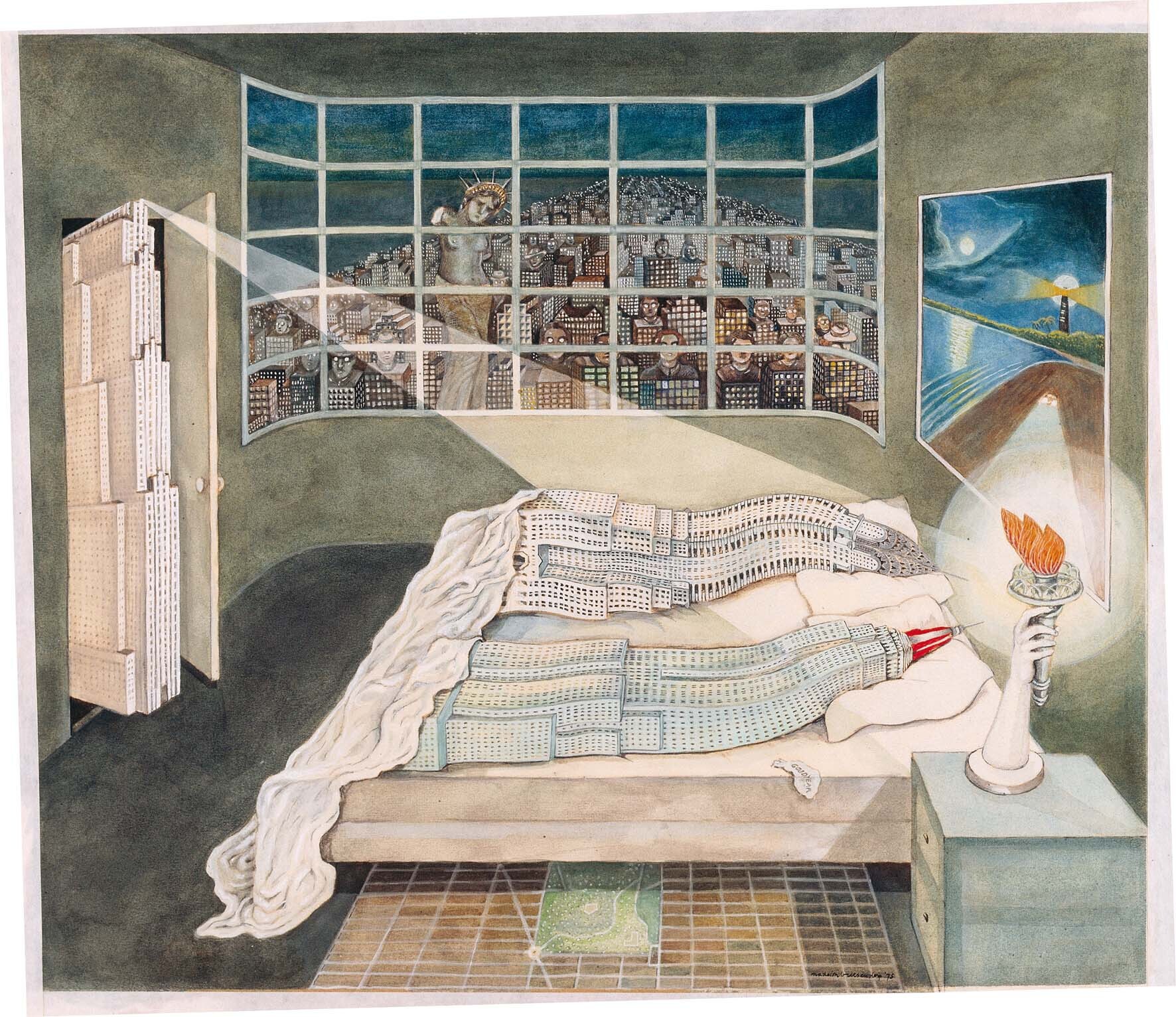

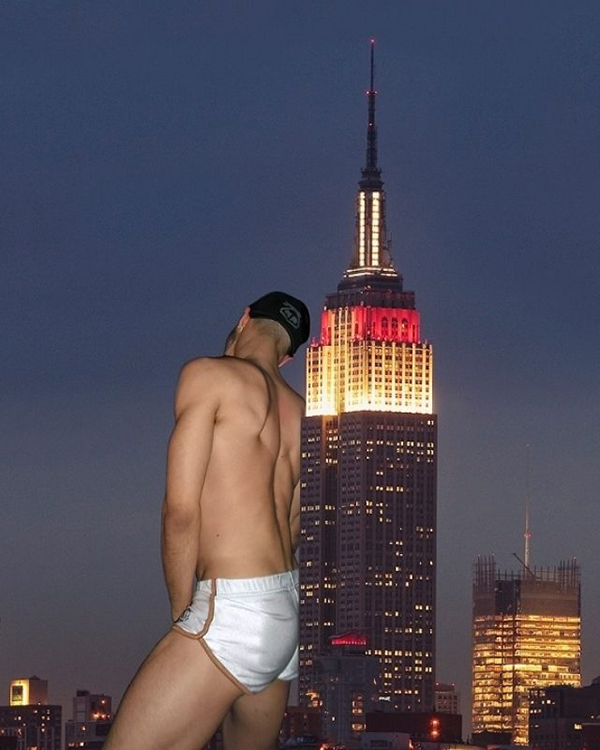

In Baren / The Bar we find formulations of queer institutional critique, such as Monica Bonvicini's "Warning! Failure Is to Follow" (2015). With her operating instructions printed on a poster series Bonvicini reveals the power play that is at work in sexual situations, but also in work situations and institutions. Madelon Vriesendorp's illustration "Reproduction of Flagrant Délit" (1975) for the cover of Rem Koolhaas' "Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan" receives, alongside Robert Getso's "NYC Go Go (Postcard from the Edge)" (2014), a sexualized rereading of the architecture of the modern city. His photo collages transform hetero-patriarchal buildings such as the Empire State and the Chrysler Building into totems of gay sexual desire.

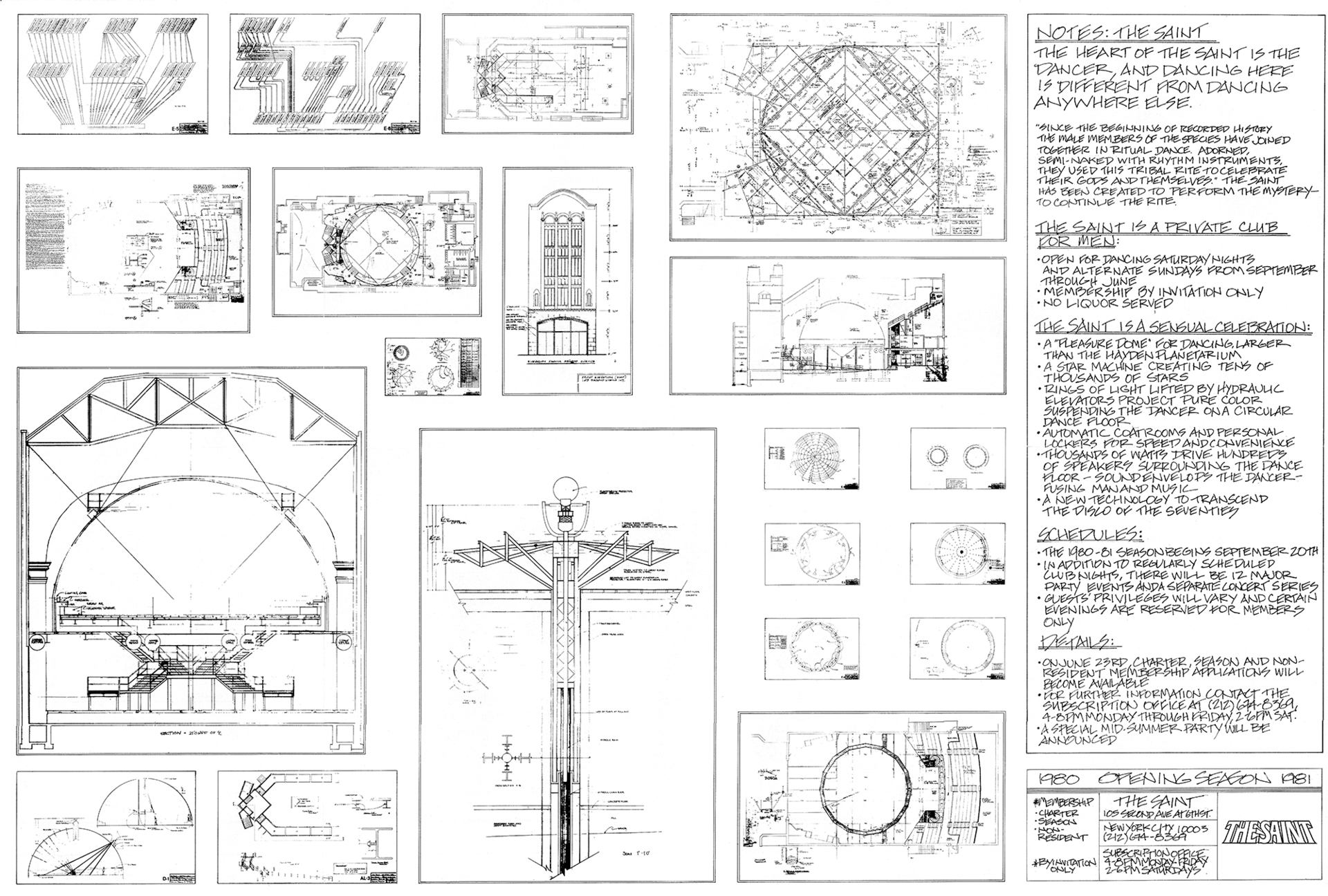

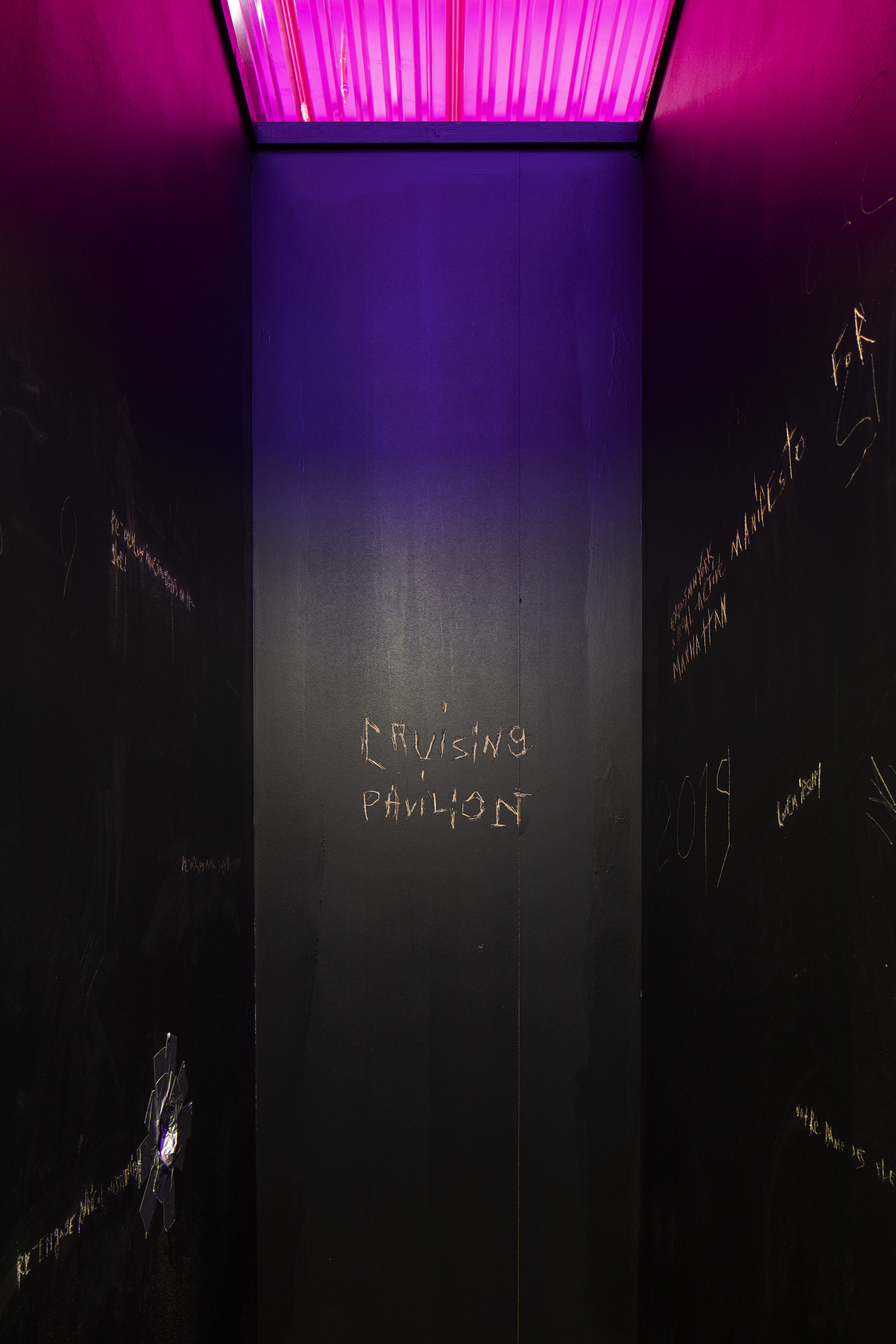

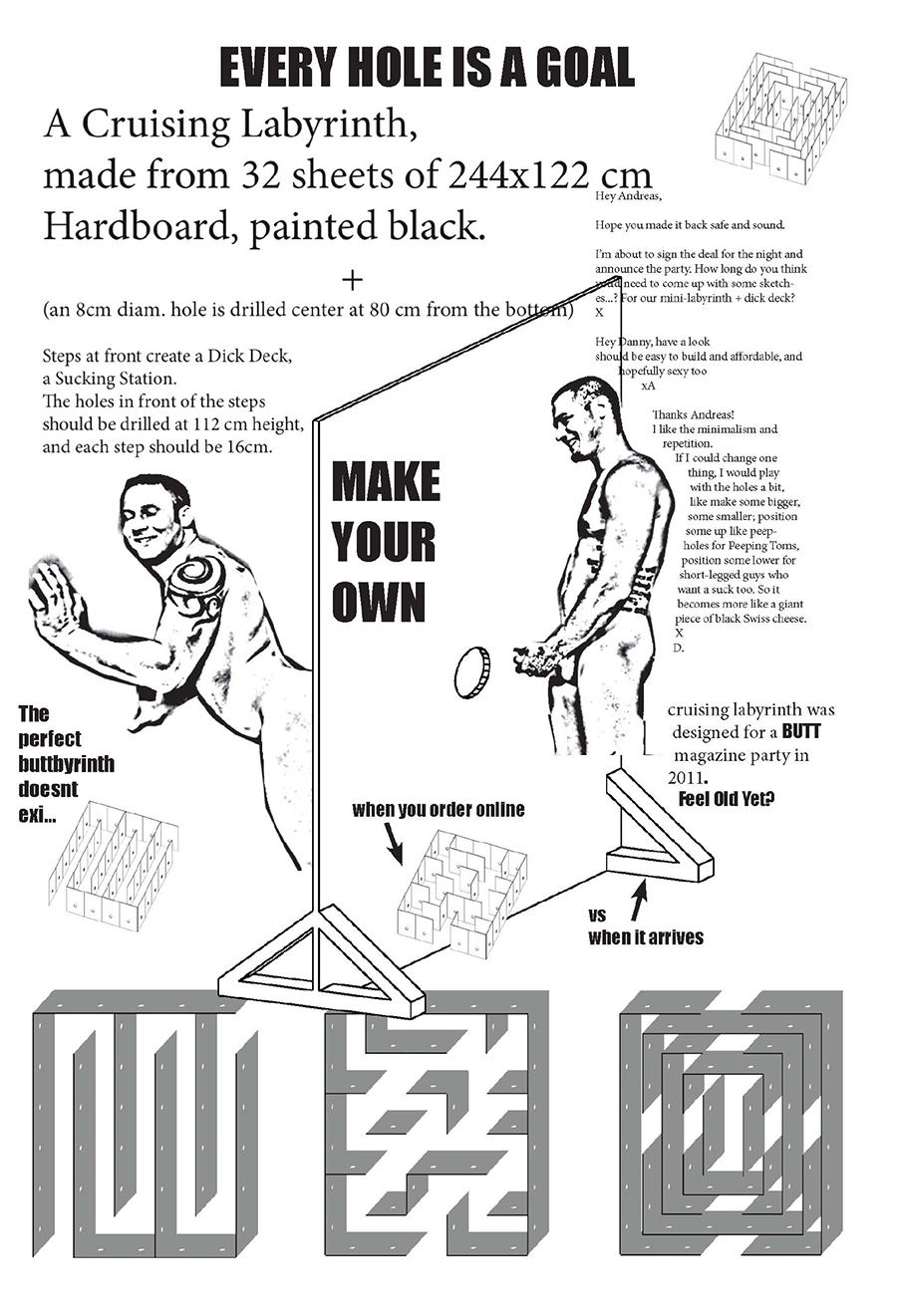

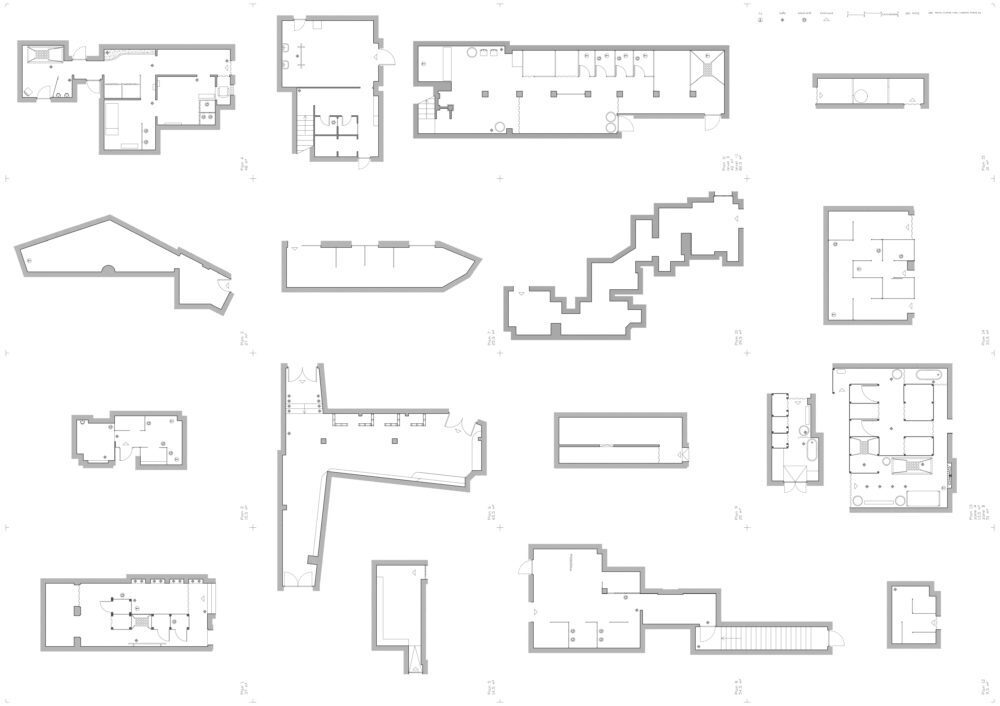

The Darkroom is dark and disorientating. Do I go left, right or straight ahead? Everywhere are supposedly used condoms, their packaging and tissues. There is a leather swing, chains and glory holes, just like in a real darkroom. In this setting, the curators have placed Henrik Olesen's "Pre-Post: Speaking Backwards" (2006). In this collection of texts, Olesen makes the dissident social and sexual practice of cruising and queer artists excluded from the European art canon visible again by telling their stories. The text-based conceptual works of very visible “masters” such as Vito Acconci, Chris Burden and Bruce Nauman, which Olesen places next to these marginalized narratives, must thus be read anew and above all queer. This part of the exhibition is also increasingly dedicated to the architectural dimension of cruising culture. Among other things, Studio Karhard's designs for the Boiler Room (2015) - a gay sauna in Berlin - show that the language of form, materials, and aesthetics are taken from this clandestine sex practice and have long since been adopted into a design language and thus into the mainstream. Pol Esteve and Marc Navarro's study "Atlas of Plans: Barcelona Dark Rooms" (2007) shows on the one hand Barcelona's distinctive network of places of gay sexual desire in 2007 and is on the other hand probably the first attempt at an architectural typology of the sex club. And with "Cruising Labyrinth" (2011 - 2019) Andreas Angelidakis even gives us instructions for building our own dark room.

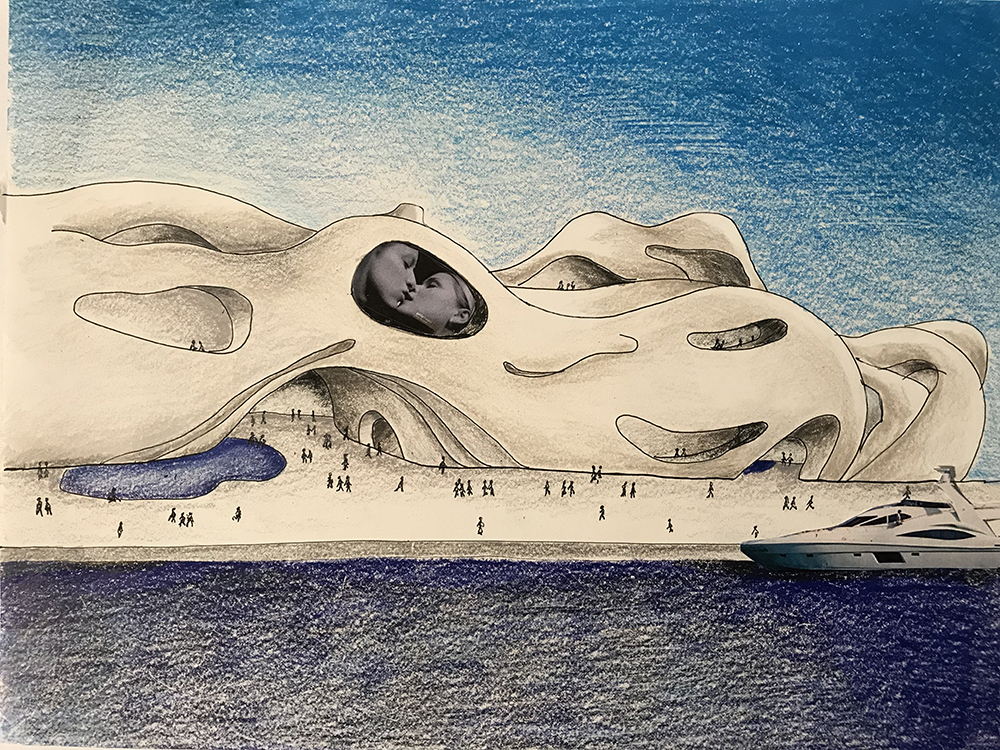

Sovrummet / The Bedroom shows us how the phenomenon of cruising has evolved over the last two decades from a local practice to a global geospatial phenomenon through dating and hook-up apps like Tinder, Grindr etc. Through direct communication with the sex partners via the apps, the geography of cruising practices has changed significantly. Meeting places are less and less often public places, but rather our private spaces. The bedroom, which is more associated with a heterosexual fantasy of reproduction, has become a new meeting place for gay men and sexual desire. Andrés Jaque's "Intimate Strangers" (2017) shows us that dating apps such as Grindr can also be abused by authoritarian regimes and states through tracking in order to explicitly attack the LGBTQ+ community. In this last part of the exhibition, video works and video games on monitors are increasingly shown. Here Shu Lea Cheng's cyberpornographic film "I.K.U." shows us (2000) a futuristic vision in which the Internet liberates us from social constructions such as sexual difference, race and gender. At the same time, however, it also makes us aware of the ambivalent nature of technology, which functions both emancipating and restricting. The revised version of the utopian project "Lesbian Xanadu (Updated Version)" (2019) is also visionary. Based on their design for a lesbian sex club from 1992 (also in the exhibition), Ann Krsul and Alexis Roworth imagine in this work a body-inclusive non-heteronormative space for sexual exploration, which is still emphasizing the feminine and thus stimulates a renegotiation of the power structures between bodies and architectures.

All artistic positions function on a subversive and/or emancipatory level. It is precisely in the combination of these works that the dimension of the phenomenon of cruising becomes clear and the exhibition imagines a utopian form of living together in which relations are fluid and unfixed and have to be constantly renegotiated. This curatorial achievement, however, lies even more in the reversal or reconfiguration of the spatial order to which the French and Danish collective refer.

The Darkroom in the White Cube

Boxen in ArkDes is located right next to Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden’s largest museum of modern and contemporary art. In fact, they share the same building. Just reopened with a new collection presentation, the Moderna Museet continues to show its works in rooms that follow the rules of the modern White Cube. In general, the White Cube still seems to be the most dominant mode of display in Western modern and contemporary art. The MMK in Frankfurt seems to be celebrating the White Cube presentation of art with the current exhibition "Museum". The Stedelijk's collection presentation in Amsterdam called BASE has been redesigned in 2017 by Rem Koolhaas' Studio OMA. Even though the freestanding walls appear in part in a labyrinthine order, the paradigm of the White Cube is followed here as well, not only spatially but also in terms of content. The classical narrative of modern art with all its “masters” and exclusionary practices, as we know it from Alfred Barr and the MoMA in New York, is furthered.

In comparison to the presentation of art in a White Cube, the scenography of "Cruising Pavilion" is all the more striking. These rooms are dark and only partially illuminated in color, loud music is played, the rooms are organized labyrinthically with corners and niches, and the surfaces are greasy and slippery, made of metal, leather, and plastic, and definitely repel liquids. On a spatial and architectural level, the curators are proposing an exhibition space that does not correspond to the classic White Cube with its normative phenomenological conditions, but refers to the vocabulary of the darkroom and gay cruising culture in general.

The modern white cube functions according to a biopolitical concept that Michel Foucault developed in his observation of the organization of modern cities[1]. These cities are the urban metropolises we inhabit today. These cities mostly emerged after the 18th century - at a time when architecture in the large metropolises was dominated by domestic bourgeois spaces and the modernist partition of cities was intended to make public space legible, transparent and disciplineable. This political history of the city attempts to establish a totalitarian order on a moral, social, political and economic level. The characteristics of the darkroom naturally run counter to this project. Dark labyrinthine places are difficult to monitor and thus allow dissident behavior, such as homosexuality, which was at that time strongly marginalized and criminalized. Today’s features of the darkroom, such as darkness and fluids, also had to be fought or at least organized by the moralistic reformers. Thus, both cities and bodies were simultaneously attempted to be organize in a totalitarian way.

The White Cube works according to the same principles: surveillance by the institution and by the other visitors promotes normative behavior and thus fixes the experience of art. The White Cube continues to favor the visual experience of art and promotes modernist contemplation in front of it, which suffocates the experience of art and locates art outside a public field of discourse. Art appears here without its political and social contexts. It appears symmetrically with very specific intervals and regularities. It is presented in isolation and thus should be elevated.

Cruising architecture and dialectics also focus on ideas of visibility and orientation and the organisation of body fluids. Cruising architecture, however, reverses the codes of modern machinistic morality into a fetish. Darkness, corners, angles, passages, wet surfaces, lubricated devices: they all use the aesthetic language and logic of the modernist city, but precisely to facilitate activities that are actually designed outside the city. Thus, a subversive space of possibility and freedom for art and bodies is created in Boxen.

Darkrooms and exhibition spaces do not seem to be politically unlike each other. Both are subject to intensive biopolitical regimes: whether by regulating the phenomenological access of the visitors to the artifacts and other subjects or by strengthening the regime of the encounter between bodies and desire. Both function as spatial frameworks and physical stages for the political construction of subject-object relationships and as such are directly linked to the power and structure of their social order, whether through their establishment or their undermining, as in the case of the darkroom.

Out of the dark

The undermining of these political mechanisms occurs in the darkroom through a potentially emancipatory quality that contemporary exhibition spaces, predominantly the White Cube, do not have - darkness. In darkness lies the metaphorical chance to infiltrate the rigid mechanisms of the construction if the sovereign subject, as we know since Enlightenment. The architectural strategies of the darkrooms are also based on visibility and orientation, but not in the sense of surveillance and totalitarian organization, but in the sense of finding-one-another. The men in darkrooms searching for each other in disorientating spaces do not know each other. One could think they have left their subjectivity outside the door. Their subjectivity is here in a not yet constituted state and has to be found first without ever being completed. The transfer of this quality to the exhibition space creates a dynamic becoming of desire rather than a rigid linear being. In this way, Cruising Pavilion creates new forms of desire, loving and living beyond the heteropatriarchal model of reproduction and homophobic paranoia that make homosexuals prisoners of heterosexual ideas of homosexuality.

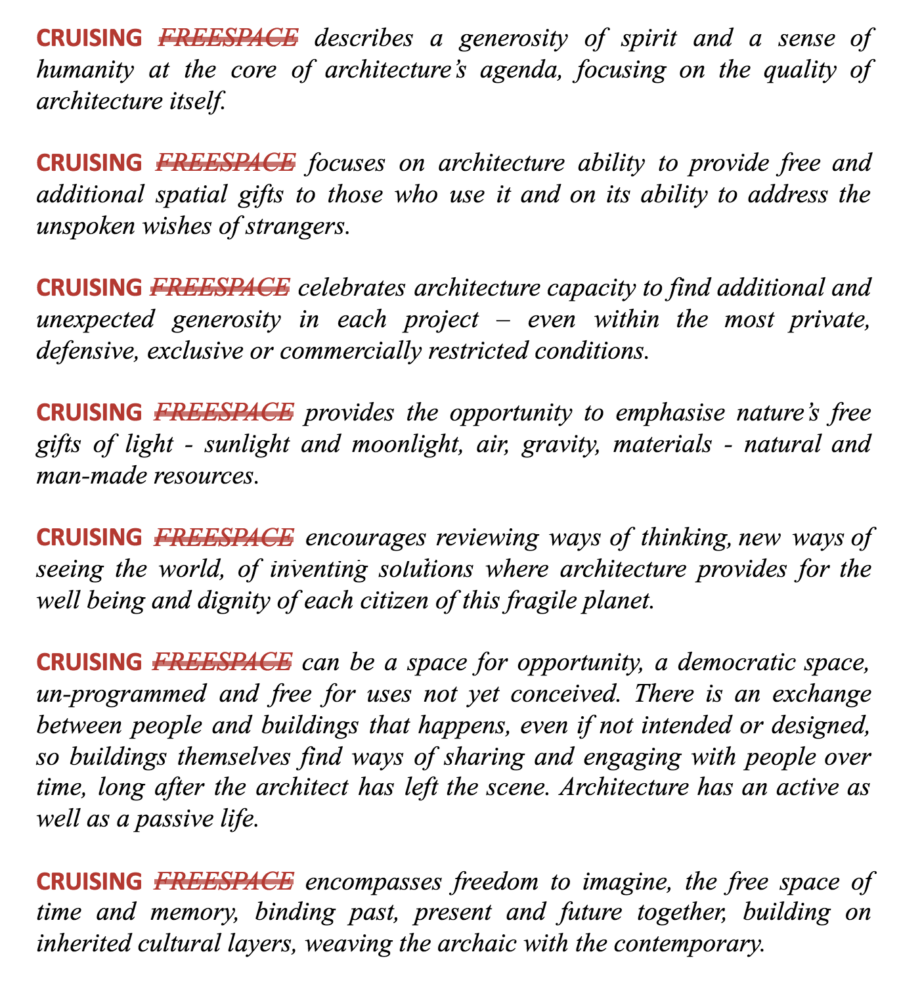

In this manner Cruising Pavilion intertwines biopolitics, architecture and the experience of art, thus becoming a deterritorialization of the human body and its subjectification. Cruising Pavilion reflects new forms of embodiment and identity formation and introduces new ways of seeing and recognizing. In its radical counter-design to the White Cube, Cruising Pavilion destroys every conventional model of true so as to become creator and producer of a truth. The exhibition becomes a place of transformation - a place of Becoming. The term Becoming is borrowed from Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. The two have coined this term in their joint rhizomatic work[2], in which they see identity in a process of becoming and away from a rigid being. They thus challenge the classical subject-object dualism. For Deleuze and Guattari, Becoming is Becoming-Molecular. The extraction of certain particles of my identity to make them available for reconfiguration with others. For example, literature, art and space are always in the process of becoming, never finished, in constant metamorphosis, never unambiguous or exclusively subject or object. This kind of relationship is also transferred to the relationship between the bodies and the art objects, which do not appear to be signified here either. The exhibition space becomes an ambiguous place in which identities constitute each other. All objects then appear non-hierarchical and as important parts of each other and of the entire exhibition. By understanding the history and spatiality of “Cruising”, we can think in new ways about what a just and inclusive city and public sphere could be. In the booklet accompanying the exhibition, the curatorial collective provides instructions that could establish new forms of curating exhibitions and living together in a process of relearning:

Redeploy Imaginations of Desire

Reengage Radical Hospitality

Reoccupy Public Spaces

Cruising Pavilion: Architecture, Gay Sex and Cruising Culture 21 September - 10 November 2019 An exhibition at ArkDes. ArkDes is Sweden’s national centre for architecture and design. It is a museum, a study centre and an arena for debate and discussion about the future of architecture, design and citizenship. Participants Andreas Angelidakis Monica Bonvicini Tom Burr Shu Lea Cheang Victoria Colmegna Earl Combs + Steve Ostrow Etienne Descloux Diller Scofidio + Renfro DYKE_ON Pol Esteve + Marc Navarro General Idea Robert Getso Horace Gifford Sidsel Meineche Hansen Nguyen Tan Hoang Andrés Jaque (Office for Political Innovation) Studio Karhard Ann Krsul + Amy Cappellazzo + Alexis Roworth + Sarah Drake John Lindell Henrik Olesen Puppies Puppies (Jade Kuriki Olivo) Hannah Quinlan + Rosie Hastings Carlos Reyes Prem Sahib Jaanus Samma S H U I (Jon Wang + Sean Roland) Max Sohl + Paul Morris Charles Terrell + Bruce Mailman Tommy Ting Madelon Vriesendorp Steven Warwick Robert Yang Trevor Yeung Cruising Pavilion are Pierre-Alexandre Mateos, Rasmus Myrup, Octave Perrault, Charles Teyssou Invited by Curator at ArkDes James Taylor-Foster [1] Michel Foucault. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège De France, 1977-78, 2009, Palgrave Macmillan [2] Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Translated by Brian Massumi, University of Minnesota Press, 1987Alke Heykes