Archive

2022

KubaParis

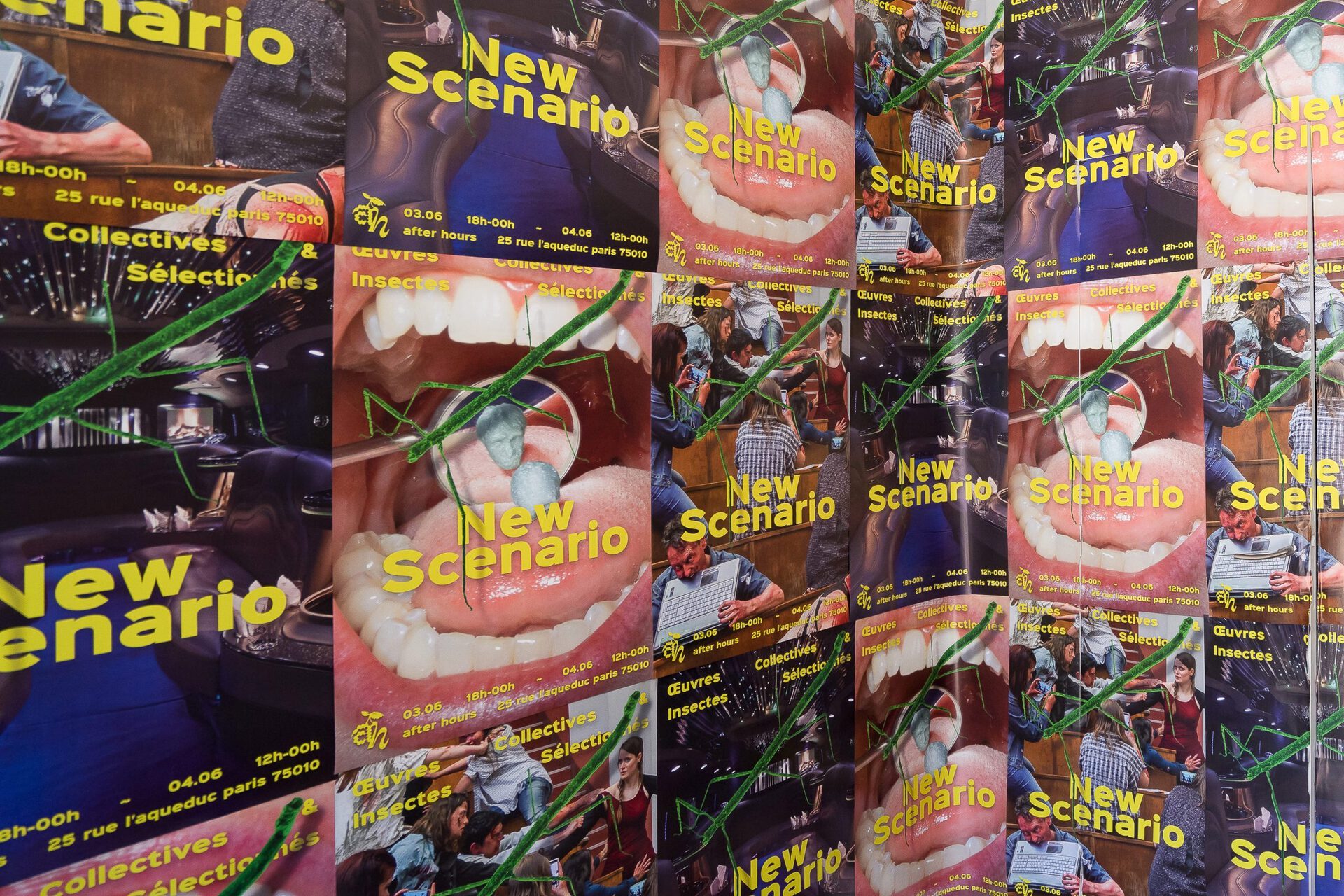

Œuvres Collectives & Insectes Sélectionnés

Location

after hoursDate

02.06 –03.06.2022Photography

New ScenarioSubheadline

48h presentation of New Scenario archives, with works by Adam Cruces, Alexander Endrulat, Aline Bouvy, Ann Hirsch, Anna Sagström, Anna Slama, Anne Fellner, Annie Pearlman, Anselm Ruderisch, Antoine Donzeaud, Antoine Renard, Aoto Oouchi, Bailey Scieszka BB5000, Bernd Imminger, Bernhard Holaschke, Beth Collar, Bradford Kessler, Bruno Zhu, Burkhard Beschow & Anne Fellner, Camilla Steinum, Carson Fisk-Vittori, Caspar Jade Heinemann, Christian Falsnaes, Christopher L G Hill, Clemence de La Tour du Pin, Connor Crawford, Courtney Malick, D3signbur3au, Daniel Keller, Debora Delmar Corp., Dorota Gaweda & Eglé Kulbokaité, Ed Fornieles, Edward Marshall Shenk, Elin Gonzalez, Emanuel Rossetti, Enrico Sutter, Eunsae Lee, Fenêtreproject (Dustin Cauchi & Francesca Mangion), Francesca Landi, Gaby Cepeda, Gregoire Blunt & Emmy Skensved, Gregor Rozanski, Hana Earles, Hannah Rose Stewart, Hilary Galbreaith, Iain Ball, Ian Swanson Inci Furni, Jaakko Pallasvuo, Jake Kent, Jakub Hošek, Jason Hirata, Jesse Darling, Joachim Coucke, Joep van Liefland, Joey Holder, Jon Rafman, Joseph Hernandez, Josephyne Schuster Brandt, Joshua Abelow, Kareem Lotfy, Keren Cytter, Kevin Kemter, Lucrezia C Visconti, Marek Delong, Maren Karlson, Maria Hassabi, Marian Luft, Mariechen Danz, Martijn Hendriks, Martin Mannig, Matt Lock, Max Kowalewski, Michael Bussell, Michele Gabriele, Michiko Nakatani Mikkel Carl, Monia Ben Hamouda, Natalya Serkova, Natasha Stagg, Nicolas Pelzer, Nschotschi Haslinger, Nuno Patrício, Nunzio Madden, Pakui Hardware, Paul Barsch, Paul Waak, Pentti Monkkonen, Philip Hinge, Phung-Tien Phan, Rachel de Joode, Rahel Aima, Rasmus Høj Mygind, Ronny Szillo, Sandra Vaka Olsen, Santiago Taccetti, Sayre Gomez, Scott Gelber, Sean Raspet, Silas Inoue, Simon W Marín, Sol Hashemi, Spencer Longo, Steph Kretowicz, Stine Deja, Sylbee Kim, Tea Strazicic, Teresa Schönherr, Thomas Payne, Tilman Hornig, Linda Reif, Timur Si-Qin, Tobias Spichtig, Tom Davis, Ullrich Klose, Va-Bene Elikem Fiatsi, Victoria Dejaco Viktor Fordell, Viktor Timofeev, Vincent Grunwald, Vitaly Bezpalov, Yves Scherer, Zack Davis, Zoe BarczaText

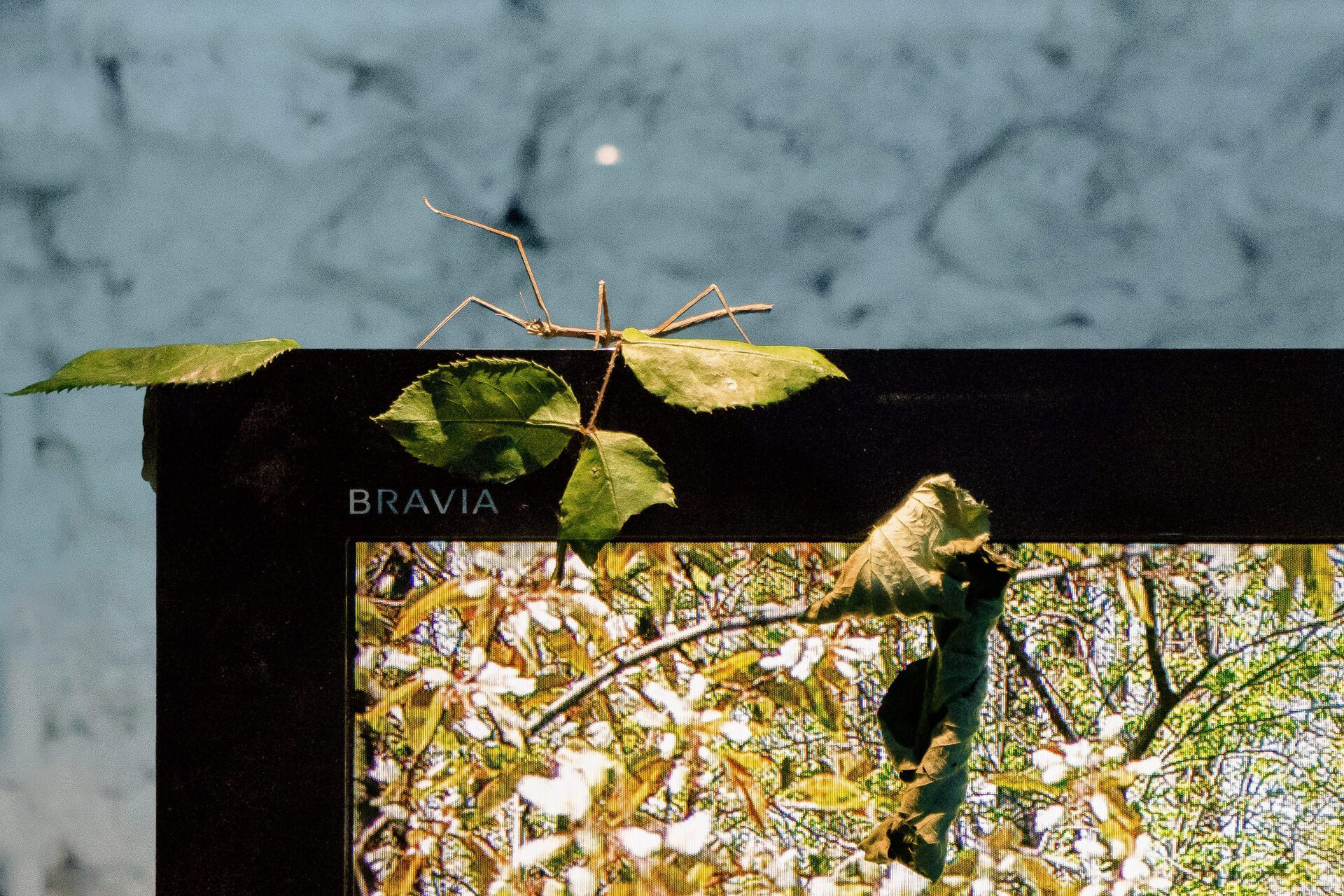

Stick insects might trigger memories of your middle school years. As a teenager, in Life and Earth Sciences class, you may have studied their individual evolution, reproduction and life cycle. The vernacular name "Devil's Rod" was granted due to their ability to metamorphose, to the point of imitating to perfection the appearance of a leaf or a twig. This adaptive strategy, wherein insects are able to blend into their environments, enables them to evade predators and ensure survival. Today, they roam throughout a strange vivarium, raised on a pedestal and lit by the glow of a television monitor — their sole cohabitant in this museum-like showcase. On the screen are randomly looping archival images from the former exhibitions of the digital platform, newscenario.net.

Founded in 2015 by German artists Paul Barsch and Tilman Hornig, the platform brings together a series of group exhibitions specifically conceived to be experienced online. It resembles nothing of the "online viewing rooms," flat and generic. The works presented have integrated whimsical places to say the least: a limousine, symbol of a bling bling civilization ("Crash", 2015), a dinosaur park ("Jurassic Paint", 2015), the seven orifices of the human body ("Bodyholes", 2016) and a university beset by zombies ("Hope", 2017 ). The last one teleports us to the rubble of a still radioactive exclusion zone ("Chernobyl Papers", 2021). More than three decades after the nuclear accident, the area is still forbidden to enter. They went there to hang the works of 40 international artists: drawings in abandoned sheds, in a telephone booth, even placed on a pile of school books on the floor. Thus disseminated in these cinematographic settings, attached to these unique contexts, the works participate in the writing of new scenarios — far from the white cube of the galleries whose sterile environment often evokes sad Apple stores.

The display device conceived for "Œuvres Collectives & Insectes Sélectionnés" operates like an ecosystem in which the roles associated with environment, object and spectator are blurred. At the same time subjects of observation and spectators of the online exhibitions, the stick insects inhabit the vitrine, such that the objects presented compose their host environment. Here, the inert and the living meet, invest in and influence one another. Subjected to the contingencies of this relationship, the installation — porous, unpredictable and moving — reacts freely. This apparatus is in line with the artists who elaborate upon what Flora Katz describes as a "strategy of decentering," as it attempts to reclaim the autonomous character of the work. What is at play in this device escapes the eye of the visitor: links are woven and imperceptible, with a logic that is not directly accessible.

But above all, the trouble caused by the installation comes from the mise en abyme that it suggests. By observing the insects, we cannot help but see ourselves, human beings, head against the screen, and wonder about what distinguishes us from these bugs. They occupy the space and infest the device, hindering the perennial conservation of the objects. Which of us — the phasma or the human — will manage to survive these shifting conditions: the species that discreetly adapts and mimics the environment until it melts into it, or the one that brutally alters said environment to meet some extravagant aspiration? In Metamorphosis, the famous novel by Franz Kafka, the main character wakes up transformed into a monstrous insect, a sort of giant cockroach. If his repulsive appearance dehumanizes him, it symbolizes the revolt of a being faced with an alienated society.

Indira Béraud