Archive

2021

KubaParis

Nothing but murmuring

Location

im laborDate

18.09 –22.10.2021Subheadline

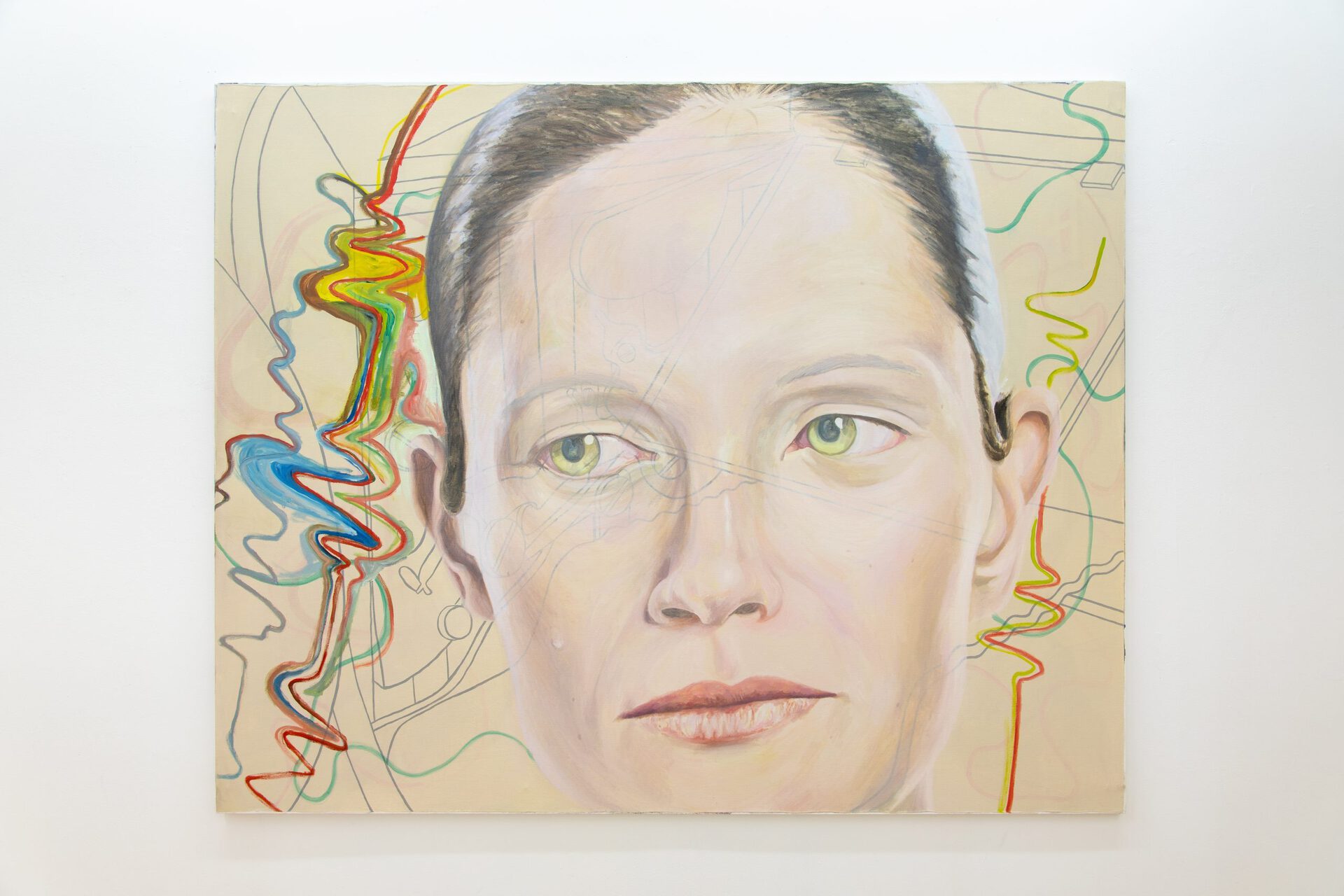

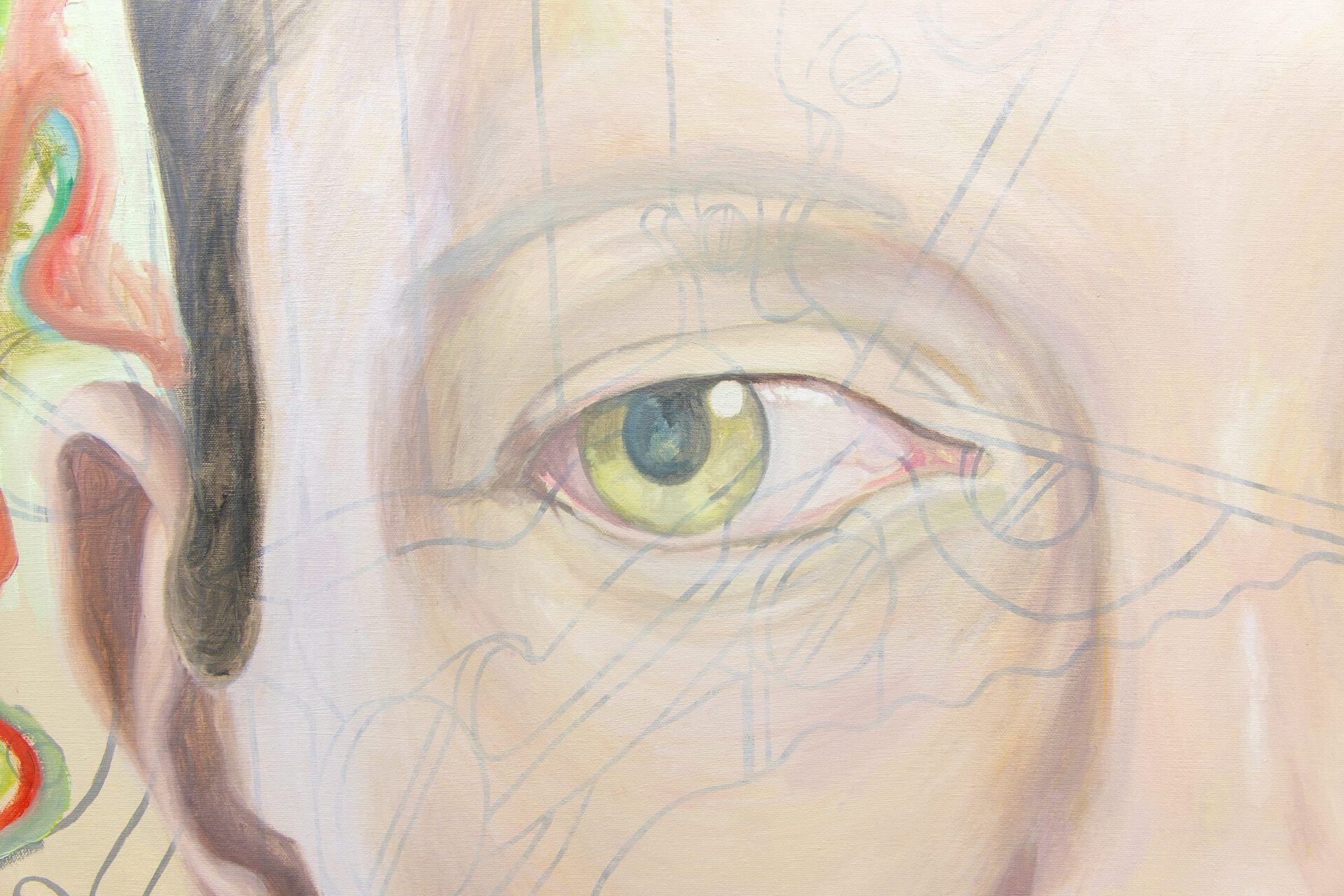

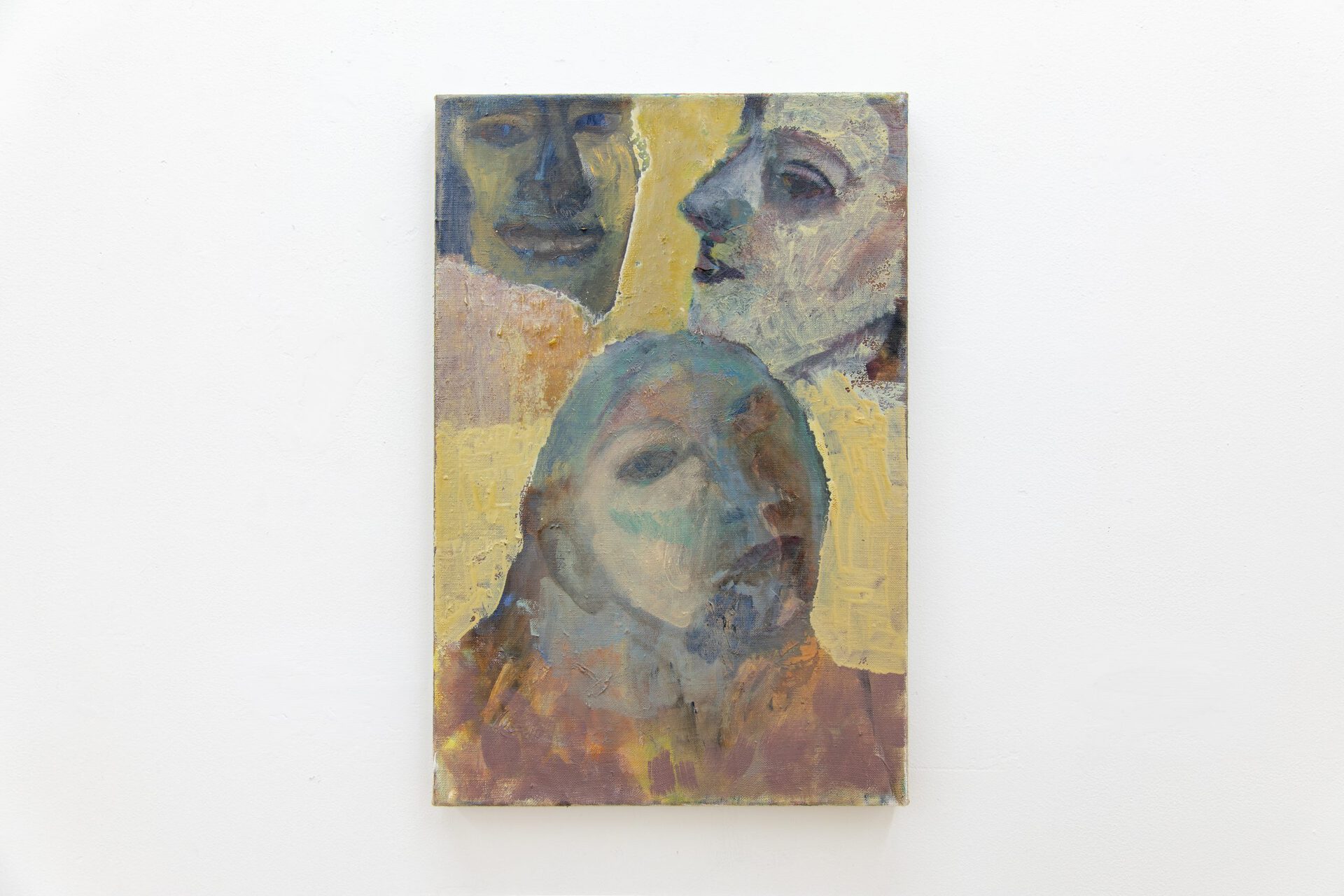

Venue__ 2x2x2 by imlabor, Tokyo, Japan Date__ September 19 - October 23, 2021 ※ Opening hours: 2pm - 7pm / Thur - Sat. Artist__ Ezra Gray, Satoshi Nakase, Olga Pedan, Sam Tierney, Barbara Wesolowska Ezra Gray (b. 1986) lives and works in Paris, France. He completed his MA in painting from the Royal College of Art (London) and BFA from Concordia University (Montreal). Select solo exhibitions include Maximum Yearn, Unit 17, Vancouver (2020); Joech God, Emalin, London (2018); Brown Space, Almanac Inn, Turin and Infinitive, Jeffrey Stark, New York City (both 2017). Select two person & group exhibitions include Super Natural, Unit 17, Vancouver (2019); Samstag, Keifholzstrasse 401, Berlin (2017); Folly, Emalin Projects, Dunmore Pineapple, Scotland; Honolulu Triennale with Sean Nicholas Savage, Honolulu, Zurich (both 2016) and Rundgang, Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (2014). Satoshi Nakase Born 1986 Osaka, Japan. Lives and works in Düsseldorf Germany and Osaka Japan. In the years 2018-2019 he was a guest student of Professor Tomma Abts at the Düsseldorf Art Academy. Recent exhibitions include: Awakening before dawn, Kunst im Hafen, Düsseldorf, Eine Ausstellung für den Zeitreisenden with Hiroyuki Masuyama, Kunstpunkte, Düsseldorf, Donotpersecuteme, Kunst im Hafen, Düsseldorf, Opening, Galerie im Schrank, Düsseldorf. Olga Pedan (1988 Kharkov, Ukraine) studied at Goldsmiths College, London and HfBK Städelschule in Frankfurt. Recent exhibitions include Reflexivity at Sundy, London; Managing Emotions at Neuer Essener Kunstverein, Essen; Spans at Jakob Forster, Rotterdam; Modelling at Pozi Driv II, London; Central Fantasy at Schiefe Zähne, Berlin and Epistlar at Issues, Stockholm. Sam Tierney (born 1988, US) is an artist living in London. He has appeared in exhibitions at Pozi Driv Two, Almanac, Lima Zulu and 3236rls, London; Rumpelstiltskin, New York; l’Atelier-ksr, Berlin; Glassbox, Paris and Podium/Grünerløkka Kunsthall, Oslo. He received a BFA from New York University, an MA in Sculpture from the Royal College of Art and is pursuing an MA in Modern European Philosophy at the CRMEP, Kingston University. Barbara Wesolowska (born 1984 Wroclaw, Poland) Lives and works in London. She graduated from the Slade in 2013 and the Royal College of Art in 2015. Recent exhibitions: Sphinx of Black Quartz, Judge My Vow, Palfrey Gallery, London, Mirror of Impalpable Nudity, GAO Gallery, London, The Vapours, Kunstverein Bamburg, In the Flesh, Peles Empire, Berlin, A Wind in the Door, Runpeltstiltskin, New York, USA, Lean days of determination, Lima Zulu, London.Text

Apparently innocent queries for explanations, which barely mask violent demands for meaning, pretend to illuminate depths but, in effect, merely delay what will not come. The explanation that would portray the significance of what cannot be understood condemns recognition with a strangely satiated oblivion. On the other hand, reason’s presupposed denial of its own intemperate efforts tempts complicity with its own omnipotence, surrendering to itself, when reason should resist itself, outdo its own powers and perhaps show its own accomplishments to be unaccomplished. If ‘the vital element of art’, by which it resists what happens, merely, to exist, is ‘spontaneity amid the involuntary’, one way to consider this exhibition is as a relinquishment of questions that it still believes it is expected to answer, which it nevertheless reacts to, but which it has productively forgotten how to articulate.1 The real pressure of imaginary demands alternately animates and constipates ‘creativity’; one work may be the result of both––often dissonantly simultaneous––actions. Something both brought to life and thwarted by that which fails to be life expresses art’s condemnation to freedom, or its ambivalent ‘release’.

I wish I didn’t know now what I didn’t know then: I wish I could release what I now know into the prehistory of its being known.

I wish I could be released from the change whereby what I did not know became known.

I wish to modify my previous not knowing as not being able to know.

May the afterlife of what I did not know act as ‘plenipotentiary for the in-itself that does not yet exist.’2

1 Adorno, Theodor W. Aesthetic Theory (trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor) Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997, p. 114.

2 Ibid., p. 252. (Plenipotentiary: A person, especially a diplomat, invested with the full power of independent action on behalf of their government, typically in a foreign country.)

Sam Tierney