Archive

2022

KubaParis

Parking Me

Location

SB34-ClovisDate

28.04 –03.06.2022Text

I talked to Zinaida on the way to Venice. She mentioned how Soviet traditions in post-Soviet Georgia where she grew up experienced a frenetic erasure, an hardcore iconoclasm fueled by years of existential threats. Were a few things worth preserving? How does stuff become important, how does that switch happen. Elsewhere I wrote that Zinaida is engaged in engagement; her work is born out of the conditions set up by the exhibition, whether physical or conceptual, not the opposite. Think of a house painter as opposed to a painter–the walls, their asperities, whether real or perceived, dictate the strokes. Beware of expressionism. I should add that Zinaida invents games too; some rules are given, others are chosen. The currently post modern interior of the exhibition space used to be a playground, not unlikely filled with games as Zinaida’s proposal for Parking Me. Lego bricks might be the impossibly curvy streets of Soviet housing blocks, color included, clutter hinting at Brussels–the table itself used to support a replica of the historical Belgian city. The house of cards rises besides. Said Zinaida: “Windows are never transparent; only apparently they pierce a facade. I moved mine from my house in the midst of a war.”

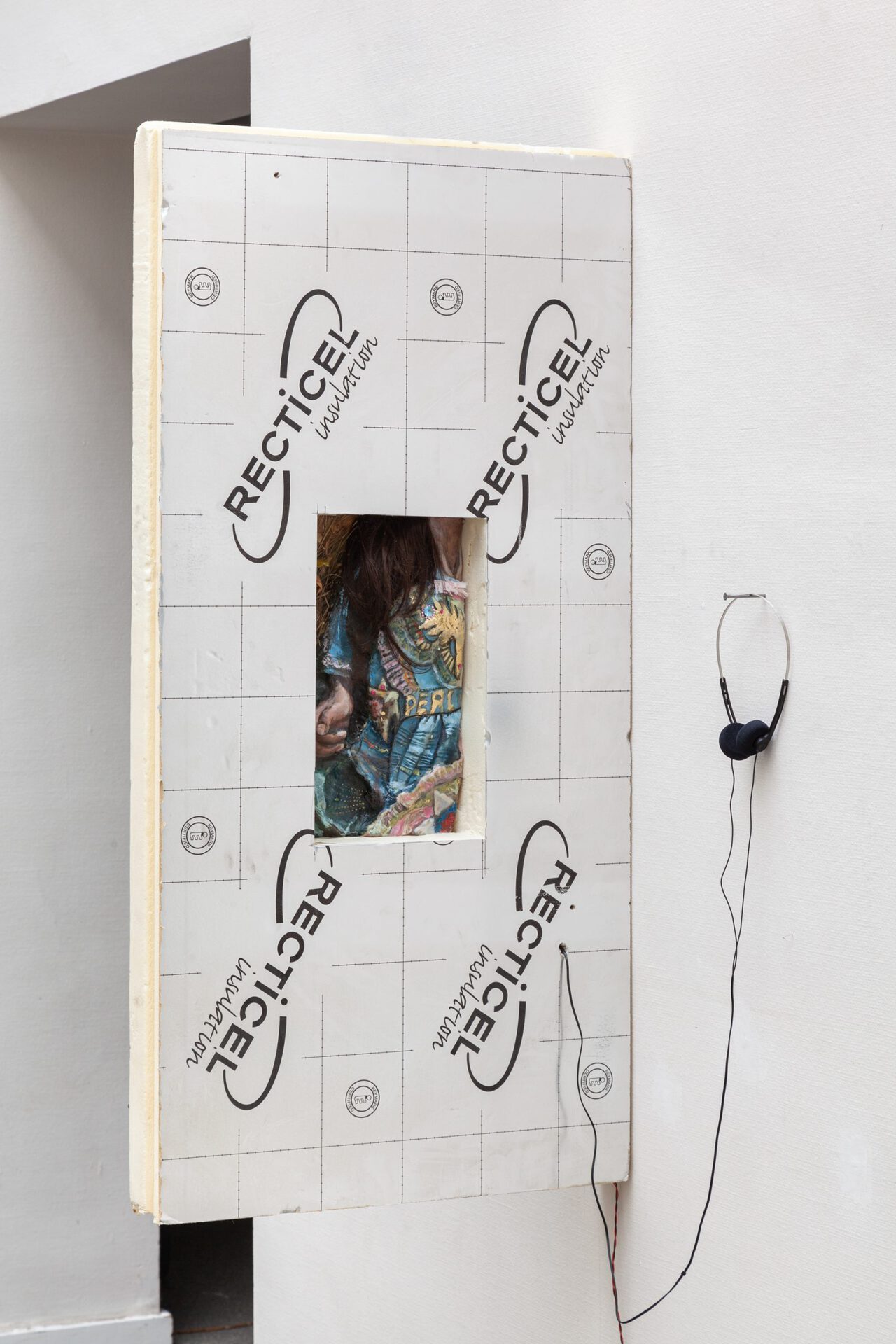

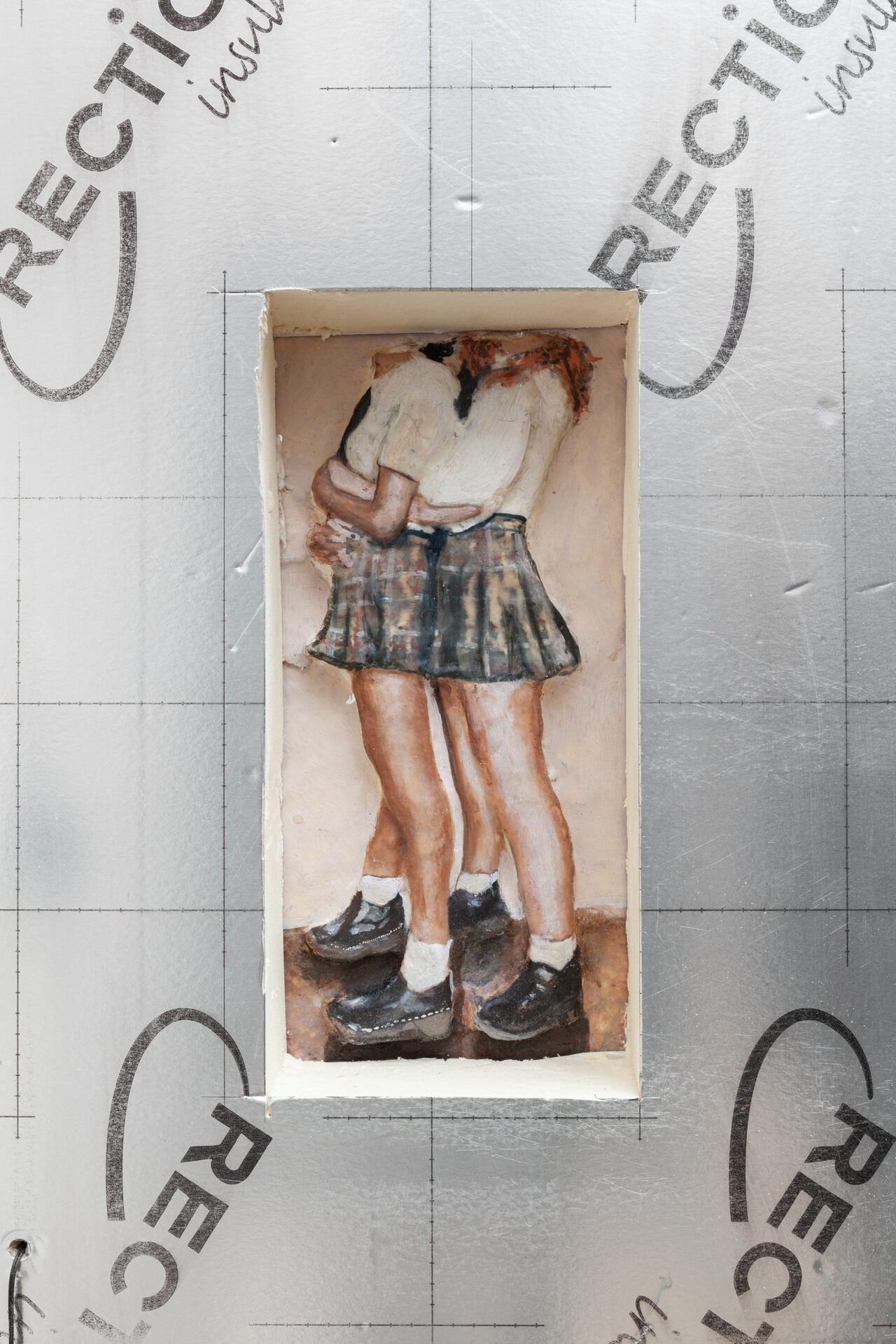

I had a chat with Mona four days ago. Her playlist consists of five songs that are necessary survival items despite how bad they are. Urgency rules over banality–who would notice the cheesy color of the oxygen mask dropping from the panel above your head. Mona mentioned how relieving it was to present the work in an art nouveau house with post modern interiors. The simple white cube is complex–its ideology poses questions that Mona’s work is not comfortable with. Indeed comfort is a trope in her proposal for Parking Me. The music soothes while we cocoon in the squeezed layers of a warm niche, while the built city of bricks runs its course outside, likely a rough one, definitely cluttered. An art nouveau interior hardly included insulating material. Heat was created but not preserved. In Mona’s words, the un-conserved interior of the exhibition space is, "the clue about something sad, the project of someone who overlooks a common order, but shows their ideology with blunt clarity, and for this reason should be respected more than a cunningly counterpart who simply sugarcoats the same intentions.” Happily we see the back of Mona’s bas reliefs in this show. Naked yet covered, they are like that little itch: we are curious at first, we obsess shortly next.

I called Fabrice on Monday. I finally understood the question of “support”–the pillar, the plinth, the foundation, the maintenance. It boils down to what we owe to the past, the urgency to cut it off, and to love it too. This is true on a personal level–our family, young friends, educators, parents, their jobs–and politically: what is our culture, what is authentic in our community of people. Fabrice mentions there is something critical in laying flat what used to be erected; pedestals are turned over, open as to avoid their usual invisibility, like windows. There must be something in between the floor and the artwork, something that gives to both. The walls of this art nouveau house-turned-post-modern-gem allowed for so little exhibit room that Fabrice’s normally hung artwork slipped off into an installation rich of sculptural elements. He called it an emancipation from the wall. In his proposal for Parking Me, signals are found everywhere, but I am especially struck by the meaningfulness of a sandwich of letters. There is something pure in letters–how can you divide or question them? They are foundational, like actual foundations onto which buildings are built, supportive in this respect. However, their combination, their being together in bricolage, can make either lots of sense or none. There is opportunism in each preservation; some of it might even be desirable.

Piero Bisello