Archive

2021

KubaParis

Puissance-de-ne-pas

Location

MarwanDate

12.03 –24.04.2021Curator

Tirza Kater & Tim MathijsenPhotography

Franziska Müller SchmidSubheadline

Puissance-de-ne-pas is part of Marwan’s year of Leakage, which is supported by the Mondriaan Fund and held (up) with the help of our community. Marwan would not be able to be what it currently is without AKINCI gallery.Text

Frozen in the before the yes

Persis Bekkering

On Puissance-de-ne-pas by Erika Roux and Victor Santamarina

Nobody welcomed the monotony of life in a lockdown. Or maybe some of us did, at first. Because it seemed to promise a caesura from the demands of the workplace and the social; a gasp of air, in a present that is always rising the bar for productivity, desire, performance. A present that extracts and exhausts bodies and resources, while presenting its forces as inevitable as gravity.

But now that the global suspension of business as usual is lasting, how many of us really feel there is plenty of time? Time to levitate, to reinvent, to squander and reflect? Time that is ours?

The promise of time stretched – though not granted to everyone – was always a fake one, since the mode of production that supports this world is left unchanged. We still live the normal normal. And the normal normal values action over inaction, decision over hesitation, yes over Bartleby’s ‘I would prefer not to’, straight lines over meandering. Machines don’t doubt, and so shouldn’t we. Machines don’t sleep, and so shouldn’t we - or only to restore our bodies for optimal labor power.

The exhibition Puissance-de-ne-pas is not so much a refusal of what featured artists Erika Roux and Victor Santamarina describe as ‘the imperative impulse of determination’, the ever accelerating forces that prod us to be like zeros and ones. Rather than merely saying nay, the works on display turn its focus on its own becoming. They are finished, they are as they should be, yet at the same time they reveal a potential-not-to-be. In doing so, they seem to linger somewhere in between. In a liminal state between yes and no, a suspension.

Santamarina’s tiny instant photos of tunnels for instance: where are we going? Are we directed in or out? The tunnel enforces a brief interruption of daylight, the ephemeral embrace of walls on four sides. We have no choice but to move along with the other vehicles in this moody capsule. That’s all we know. The frames capture the gaze en route, light emanating from the reflectors on the back of a van, a motorbike, the rear lights of a speeding car. Speed, light, direction. We find ourselves frozen in the before the yes or before the no.

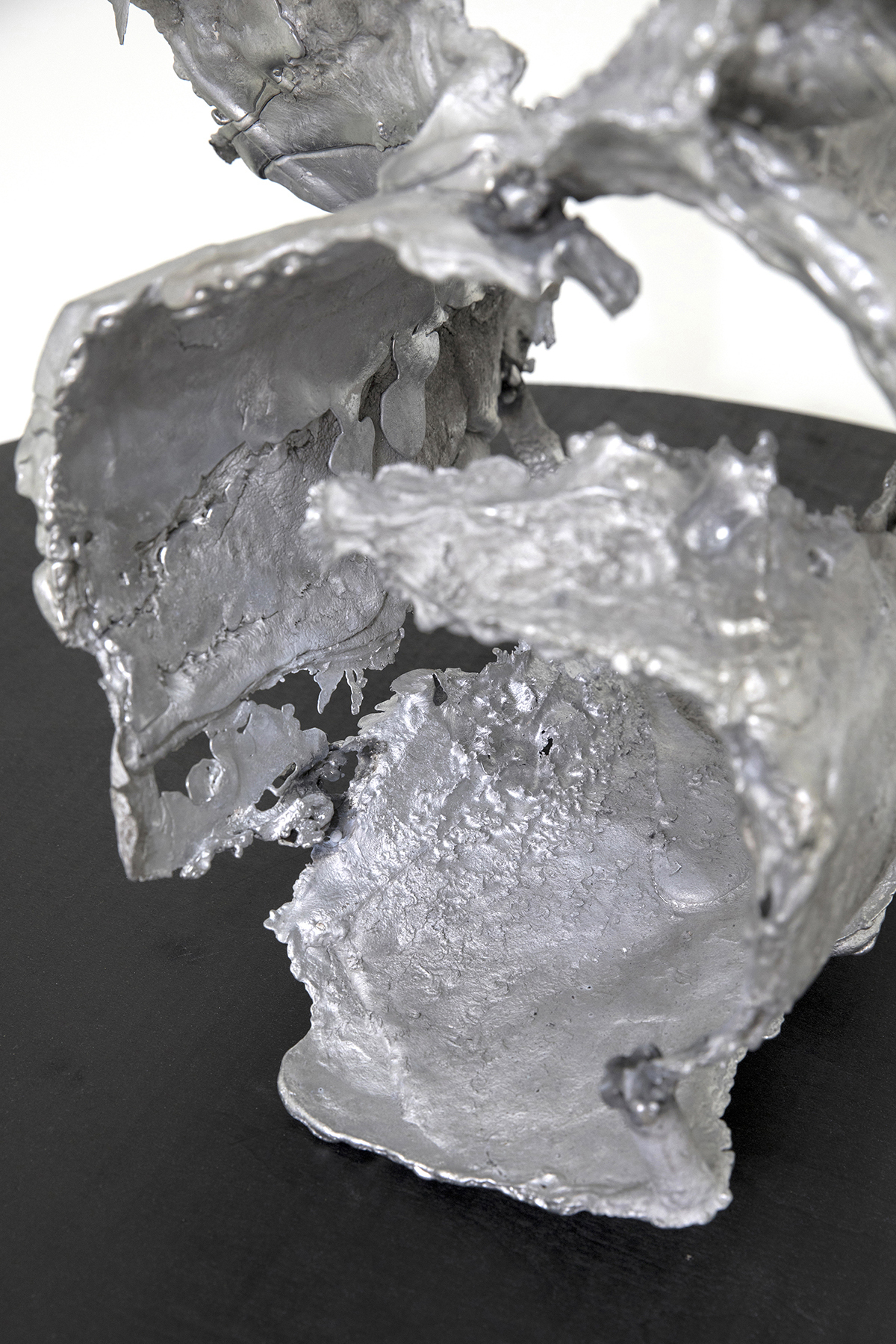

Another type of suspension is at work in the sculpture, also by Santamarina, which resembles a multi-mouthed funnel. The funnel, an instrument for casting, is a symbol of the liminal, of the metabolism between matter and form. As the funnel directs the hot, liquid metal to its desired shape, a funnel is by its very essence one-directional. In its daily use, it is supposed to separate the formless substance from the shaped, consolidated object.

Here, the funnel has multifold entries and exits. It opens up on several sides and doesn’t reveal its intended direction. It’s a glitched funnel, multiplied upon itself, leaky, cracked open.

With its several openings it resembles a heart, the motor of mammalian life. A heart receives blood and pumps it back into the body. It is an enclosure, but an open one. Sometimes the heart is taken as metaphor for the soul, yet it is not a storage space. It directs the blood as through a tunnel; its chambers hold it only temporarily, to imbue it with oxygen. The brief moment of suspension provides the sustenance of life.

The cracks and bubbles in the surface of the funnel, though, reveal the shape itself is also a cast. Therefore, the funnel refers to its object, it embodies a promise as to its potential. Yet it is a potential withdrawn. The imperfections reveal the hand of the maker, who is not a machine, nor is he trying to be. This maker can hesitate. His technique is humanly flawed. The sculpture doesn’t make an attempt to hide this.

It’s as philosopher Giorgio Agamben describes the ‘poetic act’, the act of creating. Quoting Aristotle, he draws attention to the potentiality at play in any act of making, which is at the same time a potentiality not to make, to withdraw. Every act is an actualization of a potential that could as well have been refused.

This puissance-de-ne-pas becomes even more visible in the act of making art, as art objects don’t have use value in the first instance. An artwork is the perfect example of something that has no necessity in the classic sense, and draws meaning exactly from that lack. The artist chooses to make something that could also not have been made. To make is never a force of nature like gravity.

By foregrounding this ambivalence in their works, Roux and Santamarina show the resistance at work in the poetic act. There is always the power of resistance in the act of making. Of collapsing, of going and returning, of receiving and pumping back. Of being and not being, and therefore, being both. It might very well be that it is here where life is sustained.

As Difficult, the band around which Roux’s eponymous film revolves, put it in one of their songs: ‘Have both / each is fictional and each is valuable / Not saying things should be one way or the other / Maybe both, have both’.

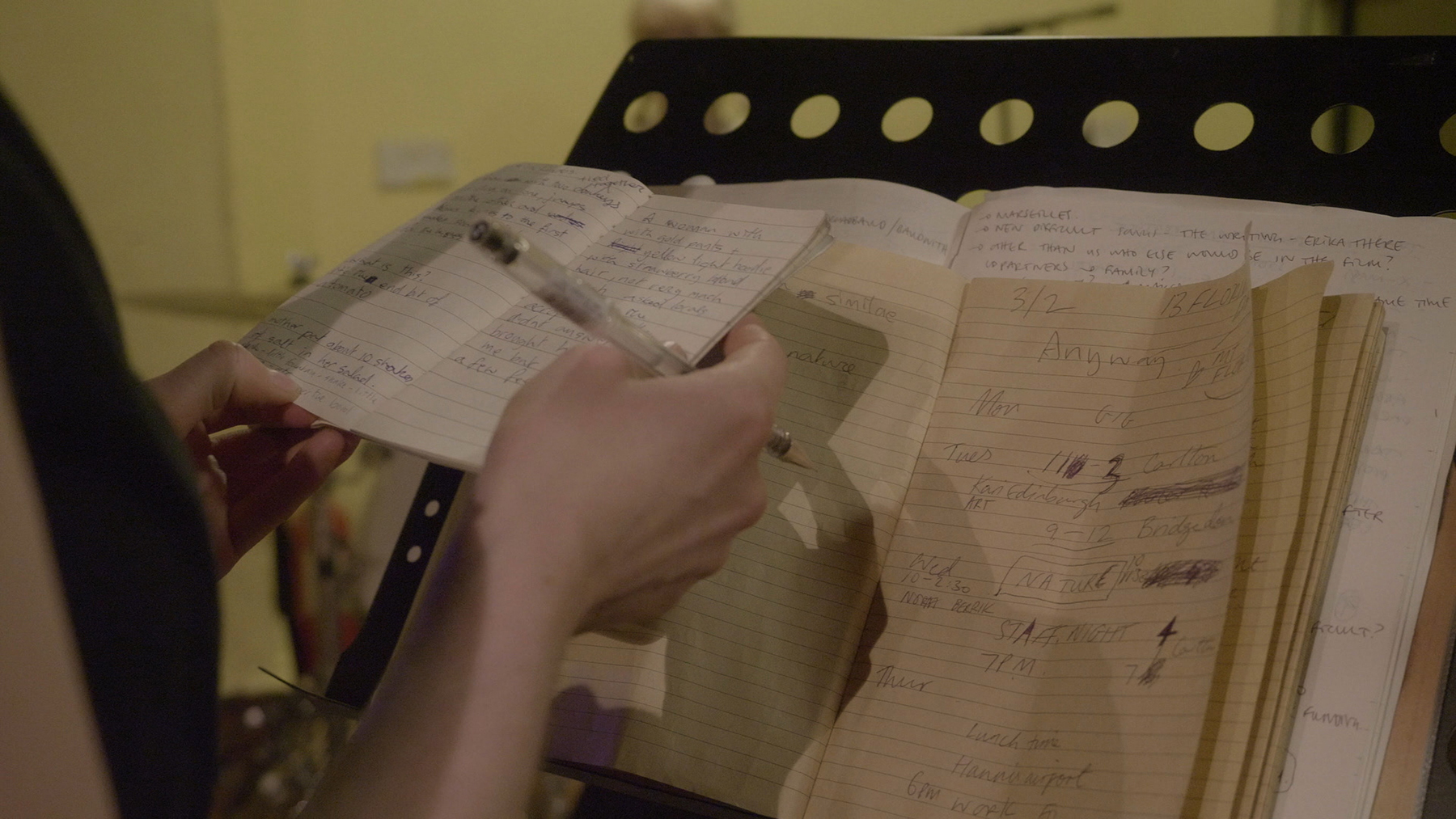

Have both, maybe. Roux films the three female band members close on the skin, in a windowless studio in Glasgow, while they rehearse new music. The camera literally glances over their shoulders into the messy notebooks where the lyrics are jotted down, a moment that feels deeply intimate, almost voyeuristic. Roux is allowed (and allows the spectator) to witness the fragile process of the creation of music, in which collaboration and friendship are more important than the anonymous industry’s standards of perfection.

‘Have both’ is a song about ambivalence, about the possibility of attaining two states of being or embracing two objectives at the same time. Have both, the singer admonishes - but she continues with a marker of hesitation: ‘maybe’. In a world that forces us to make quick decisions in order to extract the highest value, have you ever considered you don’t have to choose? That there is the possibility of abundance, no matter what we’re told? But the maybe adds a pause here, without completely undermining the force of the statement.

Likewise, maybe the works in Puissance-de-ne-pas are not so much a meditation on the in-between, maybe they are (also) both: the work and its becoming. Like the table supporting the sculpture. The unusual assemblage of the table, this hybrid of table top and trestle, seems to contain in its very shape the possibility of two states. Like the funnel, that seems to refuse a one-directional potential. As the musicians of Difficult alternate their instruments. Not because it doesn’t matter who plays what, or because they are indifferent, but because you can have both.

It’s the maybe in which the imperative impulse of determination is halted and the possibility of levitation is inserted. The possibility of ‘tarrying’, as German philosopher Joseph Vogl conceptualizes the space between inaction and action. This space, where we pause and hesitate, is important in an economy that only validates action and disqualifies hesitation as indecision. Hesitation, he proposes, is the shadow of action and achievement. It contains an analytical power in which the problems of decision-making become sharply visible. Therefore, hesitation is not so much a moment when action is resisted, but problematized.

This is enacted in many ways in Difficult. In Roux’s decision to film the band’s rehearsals and not the concert, for example. It resonates in the many beautiful close-ups of the faces of the band members. It is as if Roux puts the faces on a par with the musical instruments. On the face as much as on the instruments, the music comes into being, while we see them think and question and respond and hesitate.

Yet not every dualism is randomly welcomed. The scenes in which a band member questions Roux’s presence bring a certain tension to the texture of the film. You are my friend, she tells her, and I trust you as a friend, but that doesn’t mean I can grant you that trust automatically as an artist. Her words return the gaze to the camera. The musician is critical of the project, as the film will inevitably inscribe them, per Roux, in an artistic discourse, in the mechanizations of the art world, a world they don’t want their music to take part in.

By including these conversations in the montage, Roux brings in another element of suspension. Of drama, even. Maybe the film’s subjects won’t allow the finalization of the film, maybe they will resist becoming the object of someone else’s artistic practice. But the drama doesn’t lead up to a climax. The questions are left in the air, in between the yes and the no.

But even if these works have the potential for an incursion into the real, even where they succeed to tarry, which is essentially an act of optimism - something is haunting these works. A melancholy, maybe. Not so much a loneliness. It’s enhanced by the stark atmosphere of tunnels. The pale light in the music studio, alternated by the endless Scottish downpour, the frame rhythmically cut through by windscreen wipers. It would be wrong to interpret this melancholy as a sign of resignation, as resignation doesn’t levitate. It’s neither a nostalgia for an idealized past, where time was abundant, artists weren’t called entrepreneurs, and the collective was not a utopic yearning but a lived experience. Such a past has never existed, of course.

One could say this melancholy is an answer to the brutality of the current condition, like a structure of feeling of the contemporary. And thus, a refusal. By refusing to accept the imperative impulse of determination and mourning the loss of other futures, this melancholy might even be called political. This is also where resistance becomes visible. After all, when has sadness ever been good for business?

Persis Bekkering